Translate this page into:

A water-stable zwitterionic Cd(II) coordination polymer as fluorescent sensor for the detection of oxo-anions and dimetridazole in milk

⁎Corresponding author. yuluma163@163.com (Yulu Ma)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

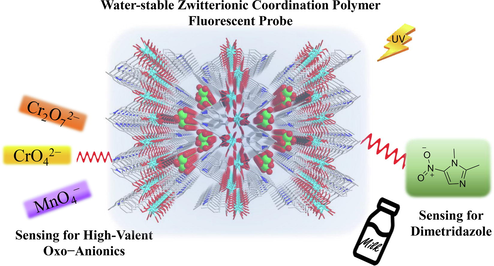

Coordination polymers (CPs) constructed by zwitterionic ligands show apparent advantages in the fluorescence sensing of toxic pollutants due to the separated charge centers on the frameworks. Besides, the construction of aqueous-phase stable and multifunctional complexes is crucial for practical applications in environmental or food safety detection. A Cd(II) 2D water-stable porous CP {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1) (flexible H2LCl=5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride) was solvothermally synthesized from good fluorescent zwitterionic organic linkers and was further characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, Hirshfeld surface analysis, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), IR spectra, elemental analysis and thermogravimetric analysis (TG). Aqueous-phase sensing studies demonstrate that complex 1 can serve as a unique bifunctional luminescent probe for highly selective, quick responsive, and multicyclic detection of three noxious high-valent oxo−anions Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− as well as dimetridazole (DTZ) antibiotic via remarkable fluorescence quenching with low limits of detection (LODs) (Cr2O72− 0.12 μM, CrO42− 0.16 μM, MnO4− 0.29 μM and DTZ 0.09 μM). Moreover, the sensor has a particular practical application potential. It obtains desirable recoveries (96.10–105.35%) for the determination of oxo-anions and DTZ in milk, respectively. The mechanism for all the turn-off responses between the framework and analytes was elaborately explored utilizing the electron transfer analytical methods and density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Abstract

Coordination polymers (CPs) constructed by zwitterionic ligands show obvious advantages in the fluorescence sensing of toxic pollutants due to the separated charge centers on the frameworks, where the construction of aqueous-phase stable and multifunctional complexes is crucial for practical applications in environmental or food safety detection. A Cd(II) 2D water-stable porous CPs {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1) (flexible H2LCl = 5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride) was solvothermally synthesized from good fluorescent zwitterionic organic linkers and was further characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, Hirshfeld surface analysis, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), IR spectra, elemental analysis, and thermogravimetric analysis (TG). Aqueous-phase sensing studies demonstrate that complex 1 can serve as a unique bifunctional luminescent probe for highly selective, quick responsive and multicyclic detection of three noxious high-valent oxo − anions Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− as well as dimetridazole (DTZ) antibiotic via remarkable fluorescence quenching with low limits of detection (LODs) (Cr2O72− 0.12 μM, CrO42− 0.16 μM, MnO4− 0.29 μM and DTZ 0.09 μM). Moreover, the sensor has a certain practical application potential. It obtains desirable recoveries (96.10–105.35 %) for the determination of oxo-anions and DTZ in milk, respectively. Mechanism for all the turn-off responses between the framework and analytes were elaborately explored by means of the electron transfer analytical methods and density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Keywords

Coordination polymers

Zwitterionic ligands

Luminescent probe

High-valent oxo−anions sensing

Dimetridazole sensing

1 Introduction

Inorganic anions play a crucial role in maintaining biological survival and ecological balance (Ma and Yan, 2022; Mukherjee et al., 2020). However, some toxic high-valent oxo-anions such as AsO43-, SeO32-, Cr2O72−, CrO42−, and MnO4− not only pose a hazard to the environment, but also may cause nausea, vomiting, cancer, kidney damage and gene mutation, owing to their strong oxidizing properties and containing hazardous heavy metals. Due to these anions having become a global threat, they are currently listed as high-risk anionic pollutants by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Xu et al., 2019a; Nandi et al., 2019).

Antibiotics are commonly used in hospitals, pharmacies, and even at home. Since the advent of antibiotics, the treatment of bacterial pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, and other diseases caused by bacteria such as streptococcus and tuberculosis has finally found a direction (Liu et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2021; Segura-Egea et al., 2016). Nowadays, antibiotics are not only a widespread drug for humans, but also can be used as feed additives for poultry and livestock to reduce diseases and promote growth (Chen et al., 2020b). However, the misuse and abuse of antibiotics have become a global problem. Medical abuse, excessive residues in agricultural products, and the water environment have caused antibiotic resistance, destruction of normal flora, low immunity, and damage to the nervous or kidneys, all of which threaten the health and survival of humans around the world (Wang et al., 2020; Yin, 2021; Butts et al., 2021). Among many antibiotics, dimetridazole (DTZ) is used as a broad-spectrum antibacterial and antiprotozoal drug. It is an effective drug for treating turkey blackhead and swine dysentery, and is widely employed in the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections in stock farming (Hu et al., 2014). However, due to the potential carcinogenic and teratogenic properties of DTZ, its use in agricultural products is strictly controlled (Ma et al., 2018; Sriram et al., 2021). Therefore, monitoring of DTZ is particularly significant in terms of food safety and public health.

Given this, the detection of these anionic contaminants and DTZ is very urgent. To date, different types of methods have been used to detect anions and DTZ, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography (GC), ion chromatography, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), etc. (Chen et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2008; Clough et al., 2020). However, most of the above-mentioned detection methods require professional and expensive instruments, need professional operations, are high costs and time-consuming, which limits their practical applications. Hence, there is a great desirability for techniques that not only can guarantee high sensitivity, fast response times, reusable, but also enable more intuitive and more straightforward detection of these pollutants. Among the numerous emerging detection methods, fluorescent chemosensors have gradually attracted people's attention in the fields of biomolecular analysis, drug detection, food security, and environmental monitoring, because of their advantages of sensitivity, selectivity, high efficiency, and visualization (Feng et al., 2021; Ramos-Soriano et al., 2021; Manna et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2019a).

Coordination polymers (CPs) based on zwitterionic organic linkers have become a new class of fluorescent sensors emerging in recent years on account of the feature of separating positive and negative charge centers, rich and tunable structures, large surface areas, diverse pores, stable and versatile architectures (Fan et al., 2020b; Wei et al., 2020; Aulakh et al., 2018). Because of the introduction of zwitterionic ligands, the synthesized CPs materials will have some unique properties. Firstly, the presence of the pyridinium salt cations offset part of the negative anionic charges of the carboxyl groups in ligands, providing conditions for the introduction of auxiliary ligands, which is conducive to the richness of structures (Wang et al., 2017). Besides, there is a weak electric field in their pores thanks to the separated charge centers (Leroux et al., 2016). And due to the introduction of polarity-inducing groups, the selectivity of host–guest chemistry is enhanced (Aulakh et al., 2015). The above reasons make this type of CPs have better selectivity when used as recognition, adsorption, or loading materials (Huang et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). However, because of the low stability of many CPs in water, to the best of our knowledge, the reported CPs fluorescent sensors based on zwitterionic ligands with dual-function of detecting high-valent oxo-anions and antibiotics in aqueous solution are very rare (Chen et al., 2020a). Therefore, CPs fluorescent probes based on zwitterionic ligands with good water stability, recyclability, rapid, and high-sensitivity detection of two types of polluting substances in the aqueous phase still need to be further developed.

Based on the above research, we constructed a water-stable coordination polymer with good fluorescence properties, namely {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1) using the zwitterionic ligands 5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride (H2LCl). Thanks to the zwitterionic linker, the framework of 1 possesses segregated charge centers. Since the negative charges concentrated on carboxylate were neutralized by Cd(II) ions, the skeleton of 1 finally shows the positive charges of pyridinium, which were balanced by free ClO4− ions in its pores. Interestingly, complex 1 presents a unique dual-responsive luminescent probe for selective, sensitive, fast-responsive, and reproducible detection of antibiotic DTZ as well as Cr2O72−, CrO42− and MnO4− ions in the aqueous phase based on luminescent quenching. In addition, the sensor can determine the oxo-anions and DTZ in milk, respectively, and the ideal recovery (95.85 % − 103.9 %) is obtained. Furthermore, the possible electron transfer or energy transfer mechanisms of complex 1 in luminescence response to different analyses were also discussed through theory calculations and a series of experiments.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials and methods

All reagents and solvents were purchased from Adamas-Beta Corporation and were used without further purification. Organic ligand 5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride (H2LCl) was synthesized according to the procedure reported in the related reference (Wang et al., 2016). The single-crystal X-ray diffraction data was collected with the Bruker APEX-II CCD detector. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were analyzed by the Elementar Vario ELIII analyzer. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were obtained in a Rigaku Dmax2500 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5456 Å). Infrared spectra were performed with an FT-IR Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 in KBr pellets. Thermalgravimetric analyses (TGA) were recorded in nitrogen atmospheres using a NETZSCH STA-449C thermoanalyzer at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. UV/vis absorption spectra were carried out on a HACH DR6000 UV–vis spectrophotometer. All fluorescence measurements were measured by using a Hitachi fluorescence spectrophotometer F-7000 spectrometer.

2.2 Synthesis of 5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride (H2LCl)

6-methylnicotinic acid (10 mmol, 1.3714 g) and 4-(chloromethyl)benzoic acid (10 mmol, 1.7059 g) were added to 50 mL CH3CN. The mixture was stirred under reflux for 6 h. After the mixture was completely cooled to room temperature, the resulting precipitate was filtered to obtain the white pure crude product, which was further washed with 95 % EtOH (15 mL × 3) to afford pure zwitterionic compound H2LCl product 2.89 g (Yield 94 %). Main IR (KBr, cm−1): 3512, 2982, 1715, 1640, 1327, 1222, 1175, 737 (Fig. S1).

2.3 Synthesis of {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1)

A mixture of Cd(ClO4)2·6H2O (0.06 mmol, 25.2 mg), H2LCl (0.02 mmol, 6.2 mg), and NaOH (0.04 mmol, 1.6 mg) was dissolved in N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF)/EtOH/water (v/v/v = 1:1:1, 2.5 mL) and was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Then the resulting reaction system was transferred to a 5 mL screw-capped glass vial. After the vial was capped, the mixture was heated to 130 °C for 72 h, and cooled down to room temperature at the rate of 5 °C/h. After being washed with the mixture of DMF and ethanol, the resulting colorless single crystals of 1 were obtained in ca.31 % yield based on the H2LCl ligand. Elemental analysis (%): calcd for C15H22CdClNO13 (Mr = 572.19): C, 31.49 %; H, 3.88 %; N, 2.45 %. Found: C, 31.12 %; H, 3.97 %; N, 2.40 %. Main IR (KBr, cm−1): 3422, 1638, 1593, 1410, 1105, 772, 622 (Fig. S1).

2.4 Crystallography

Crystallographic data for 1 were collected on a Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at 298 K using a ω-scan. The crystal structure was solved by direct methods using the SHELXL-2018/3 program package and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 using SHELXL-2018/3 and Olex2-1.3. All non-hydrogen atoms were applied with anisotropic refinement. All the hydrogen atoms were generated theoretically and placed in calculated idealized positions. Some of the solvent molecules within the pores of the framework were disordered and not located, so the SQUEEZE routine was added to the CIF file to remove the contributions of disordered guest molecules (Cheng et al., 2019). The final chemical formula of 1 was speculated by combining the structure, SQUEEZE results, TGA, and elemental analysis. Details of the crystallographic data and structure refinements are summarized in Table 1. Main bond lengths and angles are enumerated in Table S1. The CCDC number for compound 1 is 2174513.

Compound

1

Formula

C15H22CdClNO13

Formula weight

572.19

Crystal system

Monoclinic

Space group

P21/c

a (Å)

15.647(5)

b (Å)

8.296(3)

c (Å)

14.600(5)

α (°)

90

β (°)

94.992(4)

γ (°)

90

Volume (Å3)

1888.0(11)

Z

4

Dcalc (g·cm−3)

1.886

μ (mm−1)

1.360

Reflections collected

12,344

Independent reflections

4394

F(0 0 0)

1072.0

Rint

0.0241

GOF on F2

1.057

R1a, wR2b [I > 2σ(I)]

0.0285, 0.0710

R1a, wR2b [all data]

0.0344, 0.0743

2.5 Luminescence sensing experiments

For luminescence sensing, 5 mg 1 powder was immersed in 10 mL of H2O solutions containing 100 μM KnX with different inorganic anions (X = Br−, Cl −, F −, C2O42−, NO3−, S2O32−, SO32−, CO32−, SO42−, MnO4−, CrO42−, Cr2O72−), or solutions having 100 μM of different antibiotics, including dimetridazole (DTZ), norfloxacin (NFX), sulfadiazine (SDZ), penicillium (PCL), azithromycin (ATM), cefixime (CFX), amoxicillin (ACL), gentamycin (GEM). Before photoluminescence measurements, the suspensions were sonicated for 10 min. Then concentration-dependent fluorescence titration tests were determined with different concentrations of MnO4−, CrO42−, Cr2O72−, and DTZ antibiotic with the range of 0 to 80 μM. Besides, the time-dependent fluorescence experiment of 100 μM MnO4−, CrO42−, Cr2O72−, or DTZ, and the selectivity and recyclability sensing ability of complex 1 to recognize MnO4−, CrO42−, Cr2O72−, and DTZ, was also investigated.

The fluorescent detections of the three oxo − anions and DTZ in milk were also studied. Raw milk was purchased from a local pasture. According to the reported method (Niu et al., 2021), milk was diluted ten times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) (pH 7.0), which was prepared with 0.1 M H3PO4, NaOH, and KCl. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was collected and stored in a refrigerator at a temperature of about 4 °C. Then, the milk containing different amounts of oxo-anions and DTZ was analyzed by fluorescence.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structure of {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1)

The single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurement shows that complex 1 crystallizes in the monoclinic P21/c space group. The asymmetric unit is composed of a crystallographically independent Cd(II) ion, a fully deprotonated 1-(4-carboxylatobenzyl)-6-methylpyridin-1-ium-3-carboxylate (L−) ligand, two coordinated water molecules, a free ClO4− ion, and three lattice water (Fig. 1c). As illustrated in Fig. 1a, each Cd(II) ion is linked to four carboxylate O atoms from three L− ligands, and two O atoms from two water molecules with six-coordinated modes to form distorted octahedral geometry. The Cd–O distances vary from 2.222(2) to 2.402(2) Å. Each fully deprotonated V-type L− ligand can connect with three Cd(II) ions via the two carboxylate groups: the pyridyl-COO shows μ1-η1η1 chelating bidentate coordination fashion, and the benzyl-COO in the μ2-η1η1 bidentate bridging coordination mode (Fig. 1b). Two adjacent Cd(II) ions are bridged by two benzyl-COO groups to generate a [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] dinuclear subunit, with the Cd1···Cd1D distance of 3.914(11) Å (Fig. 1d and S2a). Each [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] dinuclear subunit can regard as a 4 connect node to link with four L− ligands in different directions (Fig. S1a). The [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] subunit is bridged by two L− ligands facing opposite to form a 1D S-shaped chain along the c axis (Fig. S2b), and then the chain is continuously extended by L− ligands to generate a 2D porous layer with rectangular-shaped channels along the b axis with effective aperture sizes of 12.72 × 3.00 Å2 (Fig. 1e and f). Finally, the different layers are expanded by the C — H···O hydrogen bonds between the methylene in layers and ClO4− ion in their pores into the final 3D supramolecular framework of 1 (Fig. 1g and h). It should be noted that the L− ligand constituting 1 belongs to zwitterionic ligands having separating positive and negative charge centers. The positive charges are mainly concentrated on the pyridine rings, and negative charges are primarily concentrated on the carboxylate groups. Finally, the framework of compound 1 continues the characteristics of L−. However, since the negative charges of carboxylate were neutralized by Cd(II) ions, the final framework of 1 is positively charged. The ClO4− ions that play roles in balancing the charge just exist in its pores.![(a) The six coordinated Cd(II) center of complex 1. (b) The V-type L− ligand and its coordination modes in complex 1. (c) The asymmetric unit of 1. Symmetry codes: (B) -x, y + 1/2, -Z + 5/2; (C) ×, -y-3/2, z + 1/2. (d) The [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] dinuclear subunit in complex 1. Symmetry codes:; (A) -x, -y-2, -z + 2. (e) The 2D porous layer of 1. (f) The rectangular-shaped channels of 1. (g) and (h) The 3D supramolecular framework of 1.](/content/184/2022/15/11/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.104295-fig2.png)

(a) The six coordinated Cd(II) center of complex 1. (b) The V-type L− ligand and its coordination modes in complex 1. (c) The asymmetric unit of 1. Symmetry codes: (B) -x, y + 1/2, -Z + 5/2; (C) ×, -y-3/2, z + 1/2. (d) The [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] dinuclear subunit in complex 1. Symmetry codes:; (A) -x, -y-2, -z + 2. (e) The 2D porous layer of 1. (f) The rectangular-shaped channels of 1. (g) and (h) The 3D supramolecular framework of 1.

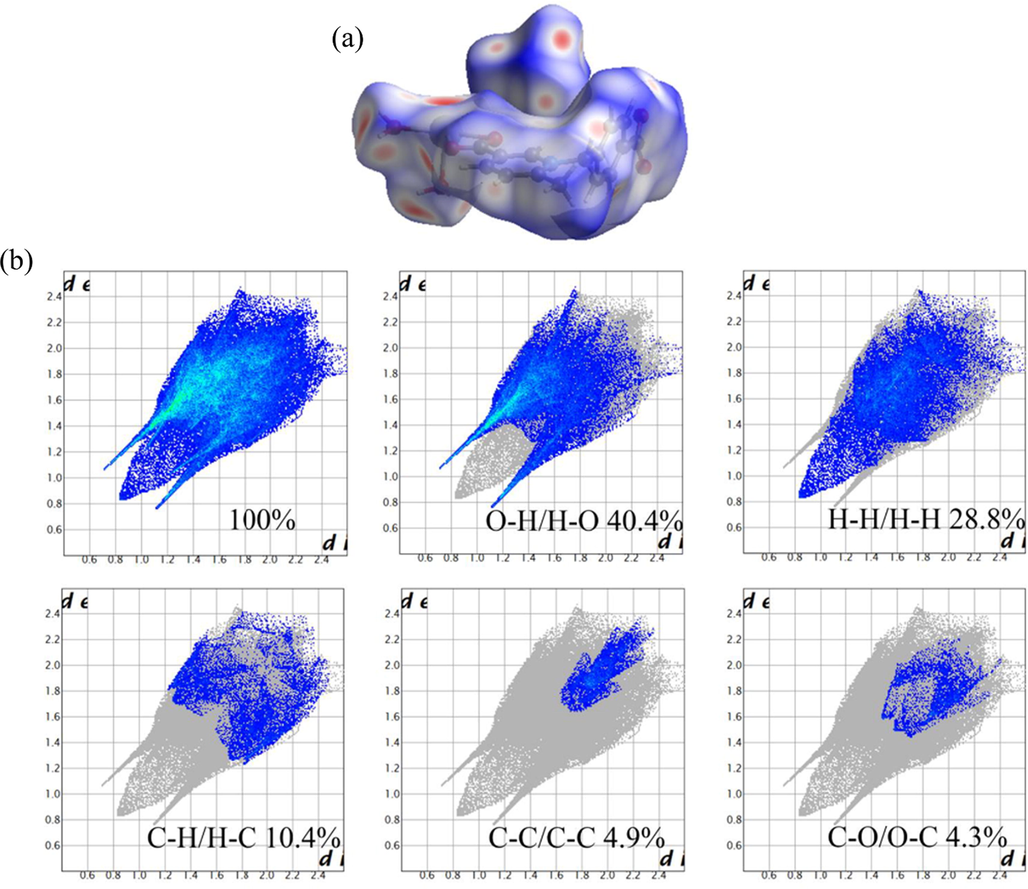

3.2 Hirshfeld surface analysis

To further analyze the nature of the intermolecular interactions and stacking mode within the crystal structure, the Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed using CrystalExplorer 3.1 program. Through the Hirshfeld surface mapped with dnorm, and the related two-dimensional (2D) fingerprint plots, the type and population of corresponding intermolecular interactions can be clarified. As shown in Fig. 2a, the bright red dots on the Hirshfeld surfaces mapped with dnorm indicate the strong intermolecular interactions, mainly originating from hydrogen bonding interactions. The two peaks of the 2D finger pattern suggest that the significant strong interactions are primarily coming from the hydrogen bond (O — H···O) between hydrogen atoms of coordinated water and oxygen atoms of carboxylates. For better quantitatively visualization of the interaction forces in the structure, the 2D-fingerprint plots were carried out (Fig. 2b). The 2D fingerprint plots indicate that there are various types of most critical intermolecular interactions in complex 1, including O···H/H···O, H···H/H···H and C···H/H···C interactions, which contribute 40.4 %, 28.8 % and 10.4 % to the total interaction forces, respectively. In addition, there are other interactions that account for less, like C···C/C···C and C···O/O···C interactions, which just accounted for 4.9 % and 4.3 %, respectively.

View of the dnorm surfaces (a) and the 2D fingerprint plots (b) of crystal structure.

3.3 PXRD and stability of 1

To check the phase purity of 1, the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of as-synthesized samples was measured at room temperature. As shown in Fig. S3, the experimental pattern of the synthesized sample match well with the simulated results generated from single-crystal X-ray structure analysis, suggesting that solid-state as-synthesized 1 was pure and homogeneous.

To explore the thermal stability, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of 1 was investigated under an N2 atmosphere from 20 to 800 ℃ (Fig. S4). TGA curve of 1 shows a continuous weight loss of 17.10 % between 80 and 270 °C, which is attributed to the release of the five lattice and coordinating water molecules (calcd: 15.74 %). From 295 to 378 °C, the weight loss is 16.77 % (calculated: 17.38 %), in correspondence with the loss of the free ClO4− ion. Above 395 °C, the structural framework began to collapse due to the decomposition of organic ligands, indicating that 1 has relatively higher thermal stability.

In addition, we investigated the aqueous-phase stability of CP 1. We soaked 1 in H2O at room temperature for 3 days and tested the PXRD of the recovered samples. The PXRD pattern matches that of the pristine sample, which shows that CP 1 has excellent stability in water (Fig. S3). The water stability of material 1 is an essential condition for its use as an aqueous phase detection material.

3.4 Luminescent properties

Coordination polymers consisting of d10 metal ions have potential as fluorescent materials (Yang et al., 2019). Therefore, the solid luminescence properties of ligand and 1 have been examined at room temperature. As shown in Fig. S5, the free ligand H2LCl exhibit an emission band at 452 nm (λex = 416 nm), corresponding to the typical π*–π transition of ligands (Zhao et al., 2020). CP 1 displays strong emission peaks with similar shapes at 430 nm upon excitation at 305 nm, which may be originated from the ligand emission. The significant intensity of the emission peaks suggests the formation of the coordination polymer can increase the conjugation of the ligands’ aromatic backbone, and can enhance the intraligand charge transfer transitions (Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). A blue shift in the emission maxima is observed, which may be due to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) (Cao et al., 2019b). The good luminescent properties of 1 urges us to study its potential applications in fluorescence recognition.

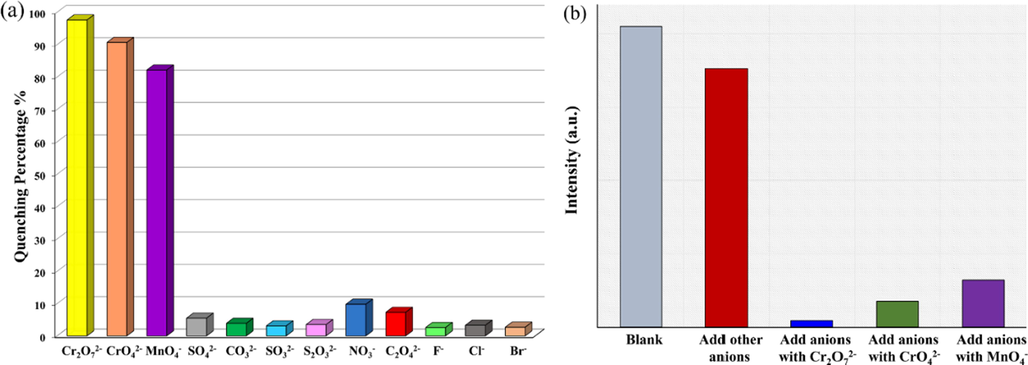

3.5 Fluorescence detection of Cr2O72−, CrO42− and MnO4− ions

The excellent fluorescence emission properties and good stability in water of 1 prompted us to explore its fluorescence sensing ability for various inorganic anions in aqueous solutions. The aqueous suspensions of CP 1 are found to be highly luminescent, with peak maxima at 436 nm. The curves remain almost similar to that observed in the case of solid samples. The slight red shift in the emission maxima may be due to the interactions between solvent and coordination polymers. As shown in Fig. 3a and S6, after adding different inorganic anions, the luminescent intensities of 1 water suspension changed to different degrees. It is noteworthy that Cr2O72− has the strongest luminescence quenching effect, with fluorescence quenching efficiency (QE) values of 97.6 %. The luminescence quenching effect of CrO42− is second, and the QE value is 90.6 %. The effect of MnO4− comes in third with QE value of 82.1 %. The quenching efficiency for Br−, Cl −, F −, C2O42−, NO3−, S2O32−, SO32−, CO32− and SO42− just was found to be 2.7 %, 3.3 %, 2.6 %, 7.3 %, 9.8 %, 3.5 %, 3.1 %, 3.9 % and 5.5 %, respectively. The QE values were calculated by the formula: QE = [(I0 − I)/I0] × 100 %, Where I0 is the initial fluorescence intensity of 1 water suspension, I is the fluorescence intensity of 1-water suspension after adding anions. The results show the luminescent intensities of 1 water suspensions are tremendously influenced by Cr2O72−, CrO42− and MnO4−, besides, CP 1 may be used as a luminescent probe to detect Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−.

(a) Comparisons of the luminescence intensity of 1 water suspension in different inorganic anions. (b) Competitive analyte test for other inorganic anions in the presence of Cr2O72−, CrO42− or MnO4− toward 1.

Given that the selectivity and anti-interference behavior of the chemosensor is one of the most essential capabilities, the impacts of potential interfering inorganic anions (Br−, Cl −, F −, C2O42−, NO3−, S2O32−, SO32−, CO32−, and SO42−) on the fluorescence-recognizing performance of CP 1 was further investigated. Results indicate that the luminescence intensity of 1-water suspension was slightly weakened by mixed anions in the absence of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, and MnO4−. However, the luminescence was utterly quenched by the addition of Cr2O72−. Similarly, in the presence of other competitive anions, CrO42− and MnO4− show notable discrimination (Fig. 3b and S7). The above results confirm that complex 1 has high selectivity for Cr2O72−, CrO42−, or MnO4−, and 1 can serve as a potentially reliable sensor for these toxic and high-valent oxo-anions in water.

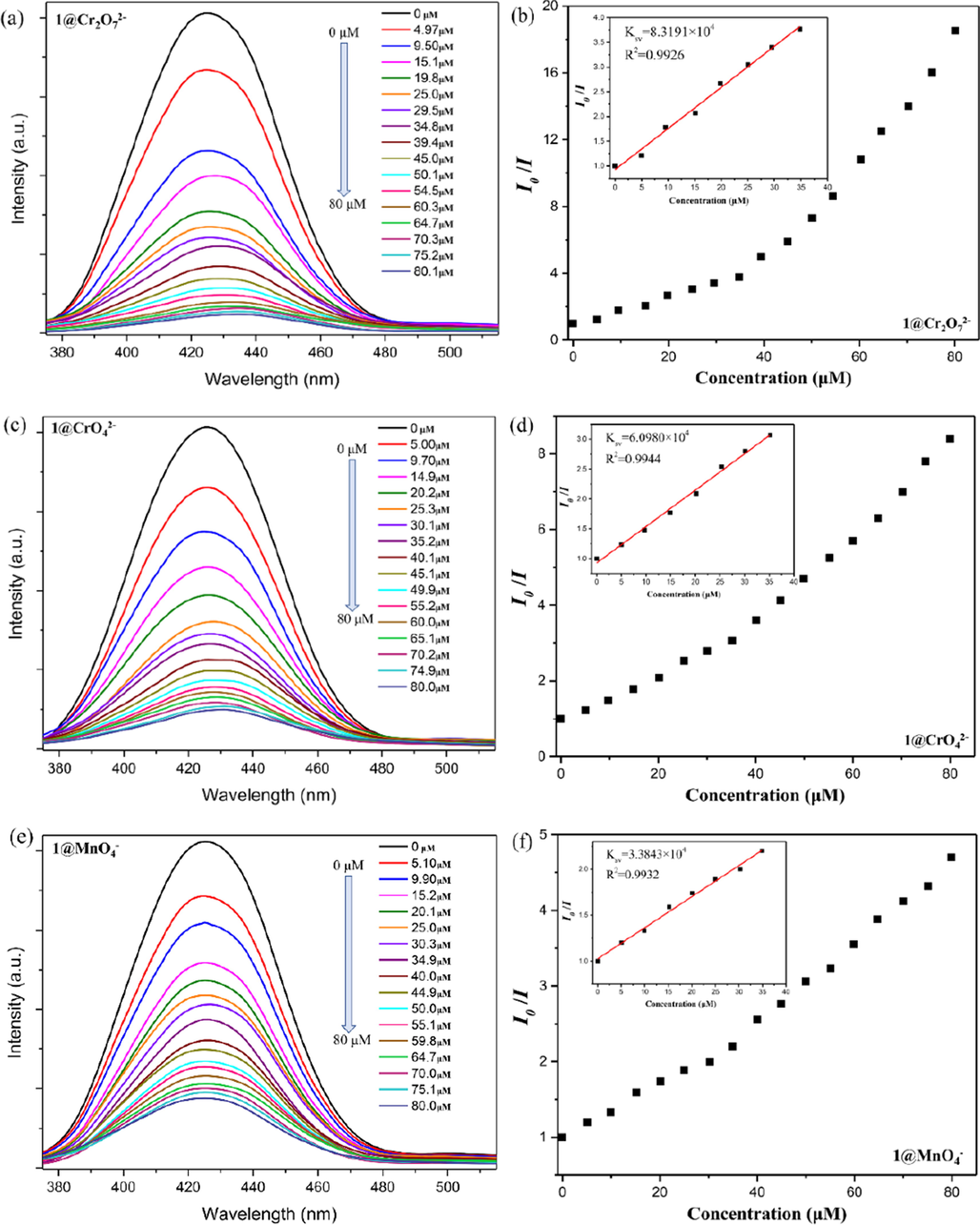

In order to evaluate the luminescent detection capabilities and limits of CP 1 toward Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− in aqueous solutions, the emission spectra of 1-water suspension were carried out with different concentrations of Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− at room temperature. As expected, with the increasing concentrations of Cr2O72−(Fig. 4a), CrO42−(Fig. 4c), and MnO4−(Fig. 4e) from 0 to 80 μM, the luminescent emission intensity of 1 was gradually decreased. To quantitatively evaluate the relationship between luminescence intensity reduction and concentration of Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−, the Stern-Volmer (S-V) equation: I0/I = 1 + Ksv × [M] was calculated for these three anions, in which I0 and I are the luminescence intensity before and after adding anions, respectively, [M] refers to the molar concentration of anions added, and Ksv is the critical indicator of the sensing ability of the fluorescence sensor, namely the quenching constant. From the linear region of the S − V plot (0 to about 35 μM, R2>99 %), the Ksv values are calculated to be 8.3191 × 104 M−1 for Cr2O72− (Fig. 4b), 6.0980 × 104 M−1 for CrO42− (Fig. 4d), and 3.3842 × 104 M−1 for MnO42− (Fig. 4f), respectively. These values for the three anions are basically at the forefront of the literature so far (Tables S2). Furthermore, to evaluate the limits of detection (LOD) for these three anions, the ratio of 3σ/K was calculated (σ is the standard error for 10 repeating luminescence measurements of blank solution, and K is the slope of the linear fitting curve of concentration-dependent luminescence intensity). The LOD values were 0.12, 0.16, and 0.29 μM for Cr2O72−, CrO42−, and MnO4−, respectively. These results demonstrate that CP 1 will be a potential anions sensor material for high sensitivity detection of Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−.

Emission spectra of the aqueous dispersion of 1 by adding different concentrations of Cr2O72−(a), CrO42− (c), and MnO4− (e). The relationship between the relative fluorescence intensity (I0/I) and the concentration of high-valent oxo-anions for Cr2O72−(b), CrO42− (d), and MnO4− (f) (inset: the Stern-Volmer plot).

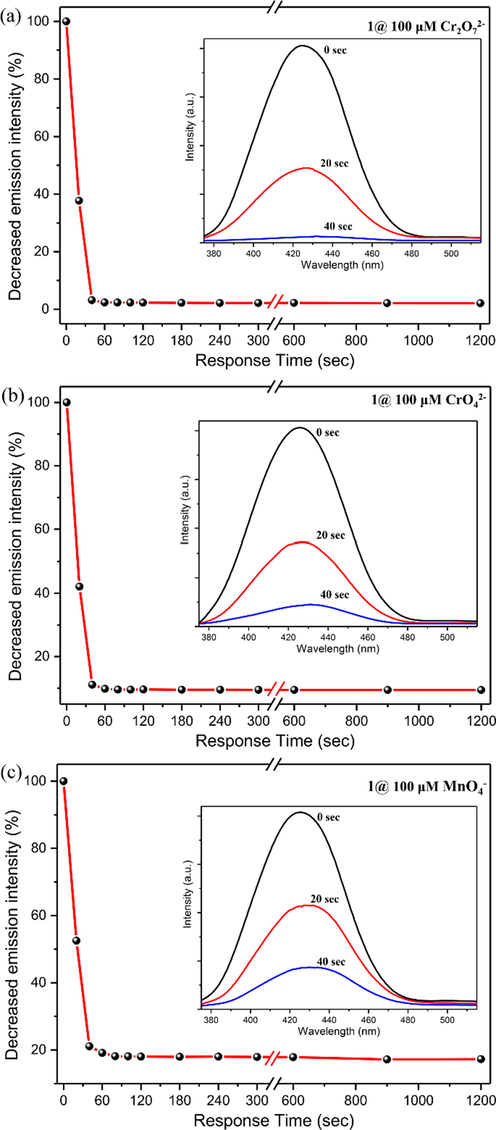

In addition, the time-dependent fluorescence quenching profile for Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− anions was investigated to test the response rate of CP 1. The results showed that a rapid quenching in luminescent intensity was observed within 40 s when 100 μM Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− was separately added to the aqueous dispersion of 1. The quenching percentages were calculated to be 62.3 %, 57.7 %, and 47.5 % for Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−, respectively, at 20 s. At 40 s, the corresponding quench percentages were 96.8 %, 88.6 %, and 78.9 %, respectively. Such time-dependent fluorescence experiments can last up to 20 mins, keeping a certain amount of the corresponding analyte in solution, and trivial changes in quenching percentages (Fig. 5a, 5b, and 5c). Therefore, we can conclude that CP 1 is a highly sensitive and quick-responsive fluorescent sensor for detrimental and high-valent oxo − anionic pollutants Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− in water.

The plot of the decrease in emission intensity percentage at different time intervals for Cr2O72−(a), CrO42− (b), and MnO4− (c) (inset: fluorescence spectra of 1 before (0 s), after (20 s), and after (40 s) addition of 100 μM of respective oxo-anion).

Considering that the recyclability of chemical sensor is an important parameter of practicability, the fluorescence sensing reproducibility of CP 1 toward Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− was studied. After each sensing experiment in the presence of 100 μM Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−, CP 1 powder was recovered by centrifugation and washed with water several times. It was found that the fluorescence intensities of 1 were well-retained, and the quenching efficiency remained basically unchanged during the five cycle experiments (Fig. 6a, 6b, and 6c). Meanwhile, the PXRD patterns of the recovered 1 sample after five detection cycles are almost identical to that of the initial sample, proving that the crystallinity and structural integrity of 1 did not change after detection testing (Fig. 6d). The high stability of this material supports its excellent recyclability. The above outcomes indicate that CP 1 can be used as a fluorescent probe of Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− with high selectivity, high sensitivity and reusability.

The quenching cycle test of 1 after adding 100 μM Cr2O72−(a), CrO42− (b), and MnO4− (c) in the aqueous phase. (d) PXRD curves of 1 after five sensing recovery cycles for respective oxo-anions.

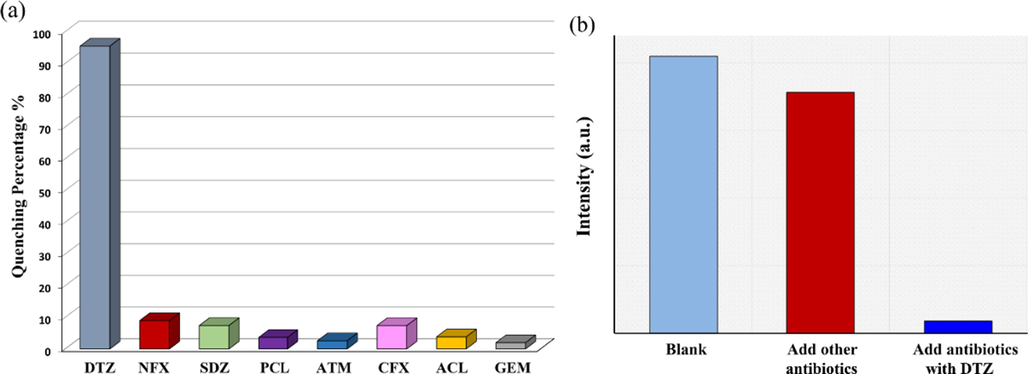

3.6 Fluorescence sensing DTZ antibiotic

The abuse of antibiotics has gradually caused problems such as antibiotic residues in food and water pollutants. Therefore, the study on the fluorescence sensing properties of 1 towards antibiotics is of great significance to the environment and human health. After adding 100 μM of different antibiotics, the aqueous solution of 1 showed various fluorescence quenching phenomena (Fig. 7a and S8). The addition of other antibiotics reveals trivial effects on the fluorescence intensity of 1 water suspension. Still, DTZ exhibited the highest quenching with a 95.4 % quenching efficiency in the fluorescence intensity of CP 1 (The QE was estimated to be 8.9 %, 7.3 %, 3.6 %, 2.5 %, 7.4 %, 3.8 % and 1.9 % for NFX, SDZ, PCL, ATM, CFX, ACL, and GEM, respectively). In the selectively and anti-interference fluorescently sensing experiments of CP 1 for DTZ, it can be found that in the absence of DTZ, the mixture of other antibiotics only slightly attenuates the luminescence intensity of the 1-water suspension. However, upon addition of DTZ, the fluorescence of 1 was completely quenched, proving that CP 1 is only remarkably sensitive to DTZ, even in the presence of other higher concentrations of antibiotics (Fig. 7b and S9).

(a) Comparisons of the luminescence intensity of 1 water suspension in different antibiotics. (b) Competitive analyte test for other antibiotics in the presence of DTZ toward 1.

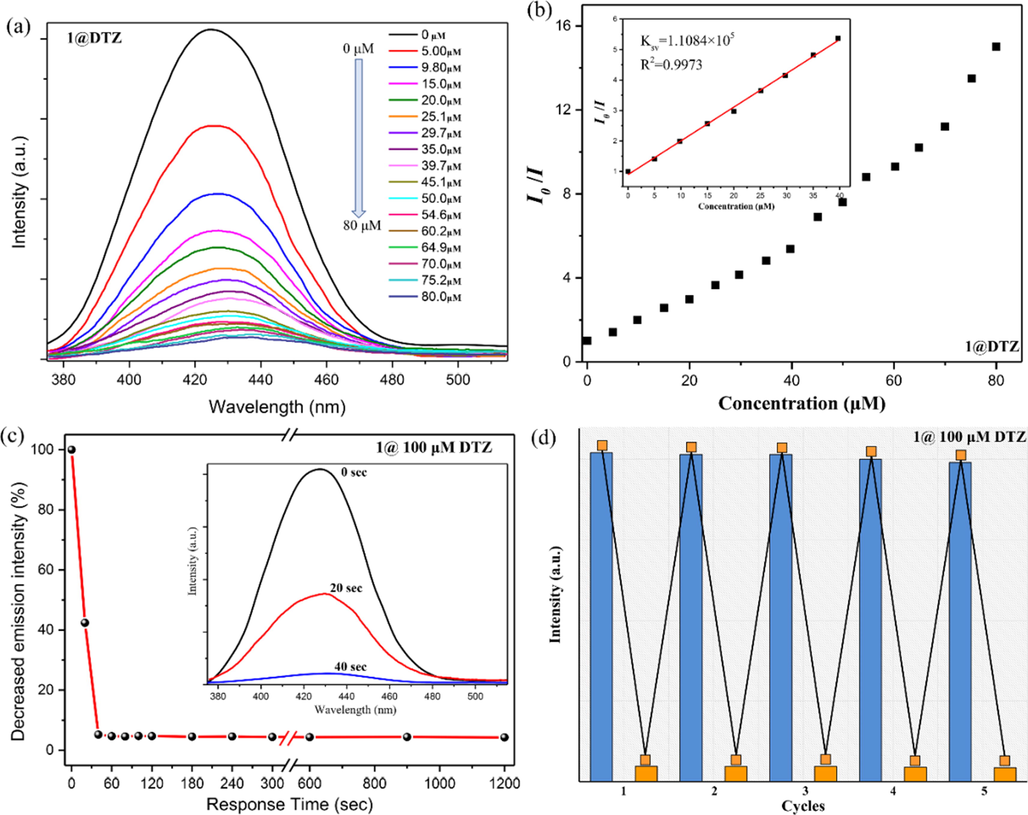

To estimate the sensitivity of CP 1 as a DTZ probe, fluorescence titration tests were performed. As shown in Fig. 8a, the fluorescence intensity of 1-water suspension gradually decreased with the increased DTZ concentration. When the DTZ concentration reached 80 μM, the fluorescence intensity of 1-water suspension at 436 nm was almost extinguished by 93 %. When we quantitatively evaluated this quenching response, we found that the fluorescence quenching efficiency of DTZ in the lower concentration range of 0 to 40 μM followed the Stern-Volmer (SV) linear fitting formula, and showed a good linear correlation (R2 = 0.9973) (Fig. 8b). After calculation, the quenching constant Ksv is found to be 1.1085 × 105 M−1, which corresponds to the higher known value of CP-based DTZ sensors reported previously (Table S3). Furthermore, based on 10 groups of blank sample measurements, the LOD was calculated to be 0.09 μM. These indicate that CP 1 is a very sensitive fluorescent probe for recognizing trace DTZ contamination.

(a) Emission spectra of the aqueous dispersion of 1 by adding different concentrations of DTZ. (b) The relationship between the relative fluorescence intensity (I0/I) and the concentration of DTZ (inset: the Stern-Volmer plot). (c) The plot of the decrease in emission intensity percentage at different time intervals for DTZ (inset: fluorescence spectra of 1 before (0 s), after (20 s), and after (40 s) addition of 100 μM of DTZ). (d) The quenching cycle test of 1 after adding 100 μM DTZ.

Considering the utility of CP 1 as a fluorescent sensor, the time-dependent recognition for DTZ was tested to investigate its ability as a rapid detection material of DTZ. As shown in Fig. 8c, a dramatic quenching in the fluorescence intensity of 1 water suspension was experienced after adding 100 μM of DTZ. The luminescence intensity was rapidly quenched by 57.6 % in just 20 s. The quenching efficiency reached 95.3 % in 40 s and remained basically unchanged in the following time, which indicates the ultrafast response of CP 1 to DTZ. On the other hand, five sensing-recovery cycle experiments confirmed that the pristine fluorescence intensity of 1 was fully recovered after being washed thoroughly with water. In addition, each addition of 100 μM DTZ could show the expected fluorescence turn-off response (Fig. 8d). The above phenomena and the unaltered PXRD pattern of 1 after five cycles (Fig. S10) verifies the structural stability and reusability of CP 1. In summary, CP 1 is a highly stable fluorescence probe for efficient, rapid, selective, and reproducible detection of DTZ antibiotic based on fluorescence emission quenching.

3.7 Mechanism for Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− and DTZ sensing

To discuss the quenching mechanism of the fluorescence emission intensity of CP 1 by Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4−, and DTZ, we performed a series of experiments. Firstly, as shown in Fig. 6d and S10, the PXRD patterns of the recovered 1 sample after multiple sensing of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4−, and DTZ are identical to that of the initial CP 1, which proves that the structural damage was not the reason causing luminescence quenching.

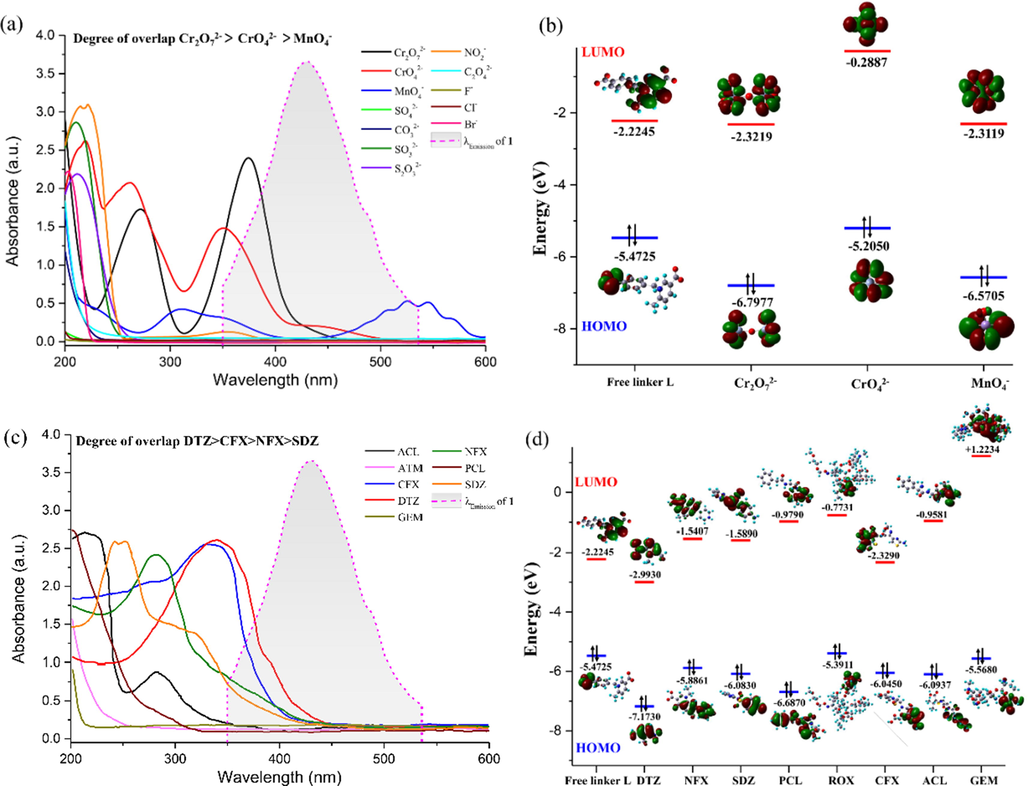

Then, the UV–vis absorption spectra of inorganic anions and antibiotics in the aqueous phase, as well as the luminescence emission spectrum of CP 1 were recorded and compared. By comparison, it can be found that the UV − vis absorption spectrum of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, and MnO4− show predominant and substantial overlap with the emission spectrum of CP 1. The overlapping degree of these three oxo − anions are in the order Cr2O72−> CrO42−> MnO4−. In contrast, the UV–vis absorption peaks of the remaining anions overlap less with the emission wavelength of the frameworks (Fig. 9a). These results suggest that the resonance energy transfer (RET) from CP 1 to Cr2O72−, CrO42− and MnO4− might occur and lead to luminescence quenching (Guo et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019b; Cui et al., 2020), and the previous research results of the fluorescence quenching degree of different anions are basically consistent with the RET mechanism. Similarly, the RET mechanism between antibiotics and CP 1 cannot be neglected. The overlapping degree between the UV–vis absorption spectra of these eight antibiotics and the emission spectrum of 1 is in the order DTZ > CFX > NFX > SDZ, whereas other drugs show negligible overlap (Fig. 9c), proving that the RET process between CP 1 and antibiotics can also generate the fluorescence quenching.

Spectral overlap between the emission spectrum of 1 and the absorption spectra of the anion analytes (a) and the antibiotics analytes (c). HOMO − LUMO energies for L linker, Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4−anions (b), and different antibiotics (d).

To gain better insight about the quenching mechanism, the photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism was also considered. Upon excitation, fluorescence quenching often occurs when the electron transfer from the conduction band (CB) of fluorescent matter to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the analyte (Xu et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2020a). To verify the existence of the PET mechanism, we calculated the energies of the highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs) of the ligand L fluorophore, Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4−, as well as antibiotics molecules (DTZ, NFX, SDZ, PCL, ATM, CFX, ACL, and GEM) using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6 − 31G level of theory in Gaussian 16. The results are shown in Fig. 9b and 9d. Compared with the three toxic and high-valent oxo-anions, the LUMO energy levels of Cr2O72− (−2.3219 eV) and MnO4−(−2.3119 eV) are slightly lower than the LUMO of L. Therefore, the excited electron can be transferred from CP 1 to Cr2O72− and MnO4− leading to luminescence quenching (Goswami et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Ghosh et al., 2022). However, the LUMO of CrO42− is at a higher energy level than that of the fluorophore L, which does not obey the quenching efficiency of CrO42−. Compared with antibiotics, the LUMO level of L is − 2.2245 eV, sufficiently higher than that of DTZ (−2.9930 eV) and slightly higher than that of CFX (−2.3290 eV), lower than that of other antibiotics molecules, so electron can efficiently transfer from the excited state of 1 to DTZ and CFX.

In summary, both the RET and PET mechanisms play an influential role in the fluorescence quenching efficacy of the toxic and high-valent oxo-anions and antibiotics, but the varying degree of contribution of energy transfer is more in line with or plays a more dominant role in the quenching mechanism of Cr2O72−, CrO42− and MnO4−. In addition, the combined effect of both PET and RET made DTZ exhibit a more sensitive luminescence response than other experimental antibiotics (Fig. 10).

Schematic diagram of 1 detection of Cr2O72−/CrO42−/MnO4− and DTZ.

3.8 Detection of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− and DTZ in milk samples

To investigate the applicability of this chemosensor in natural samples, CP 1 was used to determine the concentration of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4−, and DTZ in milk samples, respectively. The fluorescence emission spectra of milk samples without analytes were measured. And then adding different concentrations (10, 20, and 30 μM) of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4−, and DTZ to milk samples. As shown in Table 2, satisfactory recoveries of 96.10–105.35 % were obtained with relative standard deviations (RSD, n = 3) as low as 0.72–1.83 %, which indicates that the CP 1 material has the potential as a fluorescence sensor with high accuracy and good reliability for the detection of Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− and DTZ in food samples.

Analytes

Added (µM) Found (µM) Recovery (%) RSD (%) (n = 3)

Cr2O72−

10.00

9.61

96.10

1.83

Cr2O72−

20.00

19.57

97.85

1.11

Cr2O72−

30.00

28.66

95.53

0.92

CrO42−

10.00

10.46

104.60

0.72

CrO42−

20.00

21.07

105.35

1.16

CrO42−

30.00

30.66

102.20

1.45

MnO4−

10.00

10.37

103.70

1.23

MnO4−

20.00

20.09

100.45

0.82

MnO4−

30.00

29.75

99.17

0.79

DTZ

10.00

9.79

97.90

1.22

DTZ

20.00

20.18

100.90

1.18

DTZ

20.00

29.76

99.200.3470

(10)1.35

4 Conclusions

A water-stable fluorescent probe {[CdL(H2O)2]·(ClO4)·3H2O} (1) has been successfully synthesized using a zwitterionic ligand 5-carboxy-1-(4-carboxybenzyl)-2-methylpyridin-1-ium chloride (H2LCl) as a linker via solvothermal conditions. Complex 1 encompasses [(Cd1)2(μ2-CO2)2] subunits and shows a 2D porous structure, which is further extended into 3D supramolecular framework through abundant hydrogen bonds. Due to the introduction of zwitterionic ligands, 1 has segregated charge centers, and the skeleton of 1 shows the positive charges of pyridinium balanced by free ClO4− ions in its pores. Studies show that CP 1 can selectively detect Cr2O72−, CrO42−, MnO4− and DTZ from several common inorganic anions and antibiotics. The remarkable sensitivity, rapid response, and reproducible detection performance of 1 to these analytes make it a potential fluorescent probe. The possible recognition mechanism is also preliminarily studied in this paper. Moreover, this Cd(II)-metal-based CP possesses good fluorescent detection ability for oxo-anions and DTZ in milk. The work may provide a novel and practical method for the determination of anions or antibiotics in food matrix. The relevant practical research is still in progress.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by national natural science foundation of China (No. 21762049), the basic research fund of Yunnan Provincial Department of science and Technology (No.202001AU070111), the joint special project of applied basic research of Kunming Medical University of Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (No.202101AY070001-070), the scientific research fund of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education (No.2020 J0140) and the fund of Kunming Science and Technology Bureau (No.2020-1-H-035).

References

- A New Design Strategy to Access Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Frameworks from Anionic Viologen Derivates. Inorg. Chem.. 2015;54:1756-1764.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rational Design of Pore Size and Functionality in a Series of Isoreticular Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater.. 2018;30:8332-8342.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study on antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes, bacterial community characteristics and their correlation in the landfill leachates. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2021;132:445-458.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goat and cow milk differ in altering microbiota composition and fermentation products in rats with gut dysbiosis induced by amoxicillin. Food Funct.. 2021;12:3104-3119.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Incorporating Three Chiral Channels into an In-MOF for Excellent Gas Absorption and Preliminary Cu2+ Ion Detection. Cryst. Growth Des.. 2019;19:3860-3868.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coumarin-Based Small-Molecule Fluorescent Chemosensors. Chem. Rev.. 2019;119:10403-10519.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and theoretical validations of a one-pot sequential sensing of Hg2+ and biothiols by a 3D Cu-based zwitterionic metal−organic framework. Talanta. 2020;210

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotic Residues in Food: Extraction, Analysis, and Human Health Concerns. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2019;67:7569-7586.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotics and Food Safety in Aquaculture. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2020;68:11908-11919.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New multifunctional 3D porous metal–organic framework with selective gas adsorption, efficient chemical fixation of CO2 and dye adsorption. Dalton Trans.. 2019;48:7612-7618.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atomic spectrometry update: review of advances in elemental speciation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom.. 2020;35:1236-1278.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthese structure of three Zn-MOFs and potential sensor material for tetracycline antibiotic in water: {[Zn(bdc)(4,4’-bidpe)]⋅H2O}n. J. Solid State Chem.. 2020;290

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two cadmium(II) coordination polymers as multi-functional luminescent sensors for the detection of Cr(VI) anions, dichloronitroaniline pesticide, and nitrofuran antibiotic in aqueous media. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2020;239

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zn-MOFs based luminescent sensors for selective and highly sensitive detection of Fe3+ and tetracycline antibiotic. J. Pharmt. Biomed. Anal.. 2020;188

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coumarin-embedded MOF UiO-66 as a selective and sensitive fluorescent sensor for the recognition and detection of Fe3+ ions. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2021;9:16978-16984.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A fluorescent zirconium organic framework displaying rapid and nanomolar level detection of Hg(II) and nitroantibiotics. Inorg. Chem. Front.. 2022;9:859-869.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Devising Chemically Robust and Cationic Ni(II)−MOF with Nitrogen-Rich Micropores for Moisture-Tolerant CO2 Capture: Highly Regenerative and Ultrafast Colorimetric Sensor for TNP and Multiple Oxo−Anions in Water with Theoretical Revelation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:40134-40150.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The mixed-ligand strategy to assemble a microporous anionic metal–organic framework: Ln3+ post-functionalization, sensors and selective adsorption of dyes. Dalton Trans.. 2017;46:14988-14994.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel core–shell magnetic nano-sorbent with surface molecularly imprinted polymer coating for the selective solid phase extraction of dimetridazole. Food Chem.. 2014;158:366-373.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Tylosin Photoreaction Products and Comparison of ELISA and HPLC Methods for Their Detection in Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:2982-2987.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sequential Ag+/biothiol and synchronous Ag+/Hg2+ biosensing with zwitterionic Cu2+-based metal–organic frameworks. Analyst. 2020;145:2779-2788.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porous Coordination Polymer Based on Bipyridinium Carboxylate Linkers with High and Reversible Ammonia Uptake. Inorg. Chem.. 2016;55:8587-8594.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A dual-responsive luminescent metal–organic framework as a recyclable luminescent probe for the highly effective detection of pyrophosphate and nitrofurantoin. Analyst. 2019;144:4513-4519.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical and structural characterization of Hae mophilus influenzae nitroreductase in metabolizing nitroimidazoles. RSC Chem. Biol.. 2022;3:436-446.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical sensor for the determination of dimetridazole using a 3D Cu2O/ErGO-modified electrode. Anal. Methods. 2018;10:3380-3385.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monosystem Discriminative Sensor toward Inorganic Anions via Incorporating Three Different Luminescent Channels in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Anal. Chem.. 2022;94:5866-5874.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in tin ion detection using fluorometric and colorimetric chemosensors. New J. Chem.. 2022;46:7309-7328.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Green Route to Synthesize Functional Nano-MOFs as Selective Sensing Probes for Cr VI Oxoanions and as Specific Sequestering Agents for Cr2O72−. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng.. 2020;8:1195-1206.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An ultra-robust luminescent CAU-10 MOF acting as a fluorescent “turn-off” sensor for Cr2O72−in aqueous medium. Inorg. Chim. Acta.. 2019;497

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MOF-derived hollow NiCo2O4/C composite for simultaneous electrochemical determination of furazolidone and chloramphenicol in milk and honey. Food Chem.. 2021;364

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Vibration-Induced-Emission-Based Fluorescent Chemosensor for the Selective and Visual Recognition of Glucose. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2021;60:16880-16884.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotics in Endodontics: a review. Int. Endod. J.. 2016;50:1169-1184.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Well-Designed Construction of Yttrium Orthovanadate Confined on Graphitic Carbon Nitride Sheets: Electrochemical Investigation of Dimetridazole. Inorg. Chem.. 2021;60:13150-13160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multifunctional chemical sensors and luminescent thermometers based on lanthanide metal–organic framework materials. CrystEngComm. 2016;18:2690-2700.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A dye encapsulated zinc-based metal–organic framework as a dual-emission sensor for highly sensitive detection of antibiotics. Dalton Trans.. 2022;51:685-694.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emerging antibacterial nanomedicine for enhanced antibiotic therapy. Biomater. Sci.. 2020;8:6825-6839.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Metal Blending in Random Bimetallic Single-Chain Magnets: Synergetic, Antagonistic, or Innocent. Chem. Eur. J.. 2017;23:896-904.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two highly sensitive and efficient salamo-likecopper(II) complex probes for recognition of CN−. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2020;228

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A phosphorylcholine-based zwitterionic copolymer coated ZIF-8 nanodrug with a long circulation time and charged conversion for enhanced chemotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020;8:6128-6138.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal–organic frameworks with 5,5′-(1,4-xylylenediamino) diisophthalic acid and various nitrogen-containing ligands for selectively sensing Fe(III)/Cr(VI) and nitroaromatic compounds. CrystEngComm. 2019;21:2333-2344.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel magnesium metal–organic framework as a multiresponsive luminescent sensor for Fe(III) ions, pesticides, and antibiotics with high selectivity and sensitivity. Inorg. Chem.. 2018;57:13330-13340.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A carbazole-functionalized metal–organic framework for efficient detection of antibiotics, pesticides and nitroaromatic compounds. Dalton Trans.. 2019;48:2683-2691.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two new luminescent ternary Cd(II)-MOFs by regulation of aromatic dicarboxylate ligands used as efficient dual-responsive sensors for toxic metal ions in water. Polyhedron. 2019;159:32-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- One novel Cd-MOF as a highly effective multi-functional luminescent sensor for the detection of Fe3+, Hg2+, CrⅥ, Aspartic acid and Glutamic acid in aqueous solution. J. Solid State Chem.. 2022;310

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Distribution and ecological risk assessment of typical antibiotics in the surface waters of seven major rivers. China. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts. 2021;23:1088-1100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A zwitterionic ligand-based water-stable metal–organic framework showing photochromic and Cr(VI) removal properties. Dalton Trans.. 2020;49:10613-10620.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two novel lead-based coordination polymers for luminescence sensing of anions, cations and small organic molecules. Dalton Trans.. 2020;49:5695-5702.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104295.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 3

Supplementary data 3