Translate this page into:

An insight to catalytic synergic effect of Pd-MoS2 nanorods for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction

⁎Corresponding author. qyoung@ustc.edu.cn (Qing Yang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

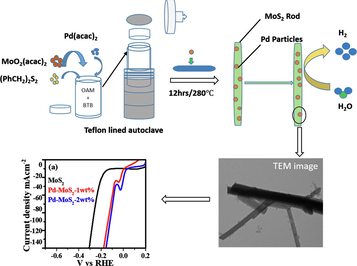

The electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is a sustainable energy production route using green chemistry. Transition metal dichalcogenides' application in catalytic hydrogen production is limited due to a lack of solutions that simultaneously address intrinsic activity, increased surface area, electrical conductivity, and stability problems. Herein we address these issues simultaneously by modifying the electronic structure of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanorods using a low content of Pd (1 wt% and 2 wt%) dopant via a facile colloidal solvothermal route. The resulting MoS2 nanorods doped with (1 and 2 wt%) palladium demonstrate current density of 100 mA/cm2 at quit lower over-potentials of 137 mV and 119 mV than 273 mV for pure MoS2 nanorods, accompanied by high stability. This research proposes a strategy for designing high-performance HER electrocatalysts that work in acidic medium. In addition, the Tafel slop calculated for MoS2 is 112 mV/dec whereas for 1 and 2 wt% Pd-MoS2, the Tafel slopes are 70 mV/dec and 46 mV/dec.

Keywords

Transition metal dichalcognides

Catalytic hydrogen production

Intrinsic activity

Electrical conductivity

Stability

Solvothermal

1 Introduction

In the current economic scenario, we require more and more efficient technologies in every field due to increasing energy demand. The current high reliance on non-renewable fossil fuels (which are rapidly becoming unsustainable) has diverted the attention quickly and more deeply than in the past. As a result, scientists are putting out every effort to find a sustainable, renewable, and clean energy source in order to address energy concerns (Liling et al., 2020; Liling et al., 2019). The electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution process (HER: 2H+ + 2e- →H2), which is critical for producing clean hydrogen energy, is one such clean energy generating phenomena (Jingying et al., 2020; Zexing et al., 2012). The lack of a cost-effective alternative for Pt has hindered the scale-up of hydrogen electrochemical generation for decades; comparable catalytic compounds are largely confined either by low catalytic performance or a finite lifespan (Zexing et al., 2021; Seh et al., 2017; Yang, 2016). As a result, low-cost, high-stability, and high-natural-abundance catalysts are required, as well as catalysts that would not become obsolete and will not obstruct HER implementation. Until recently, Pt/C was indeed the gold standard catalyst for hydrogen production (Ma, 2014). Recent research suggests that Mo based materials such as MoO2 could be a promising non-noble-metal electrocatalyst for HER (Baohua et al., 2017). MoS2 has been considered as particularly favorable for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) since the activity of its metallic edges (GH = 0.06 eV) was theoretically anticipated by Norskv and co-workers, and later experimentally confirmed by Jaramillo and co-workers (Hinnemann, 2005; Jaramillo, 2007). The following are the main governing concepts for optimizing MoS2 catalytic efficiency: 1. increase the density of atomically under-coordinated absorption sites in the trigonal prismatic phase (2H) MoS2 by revealing edge sites or introducing in-plane sulfur vacancies (SVs) (Karunadasa, 2012; Kibsgaard et al., 2012; Tsai, 2017). Though, unleashing the inherently high activity is restrained by the semi-conducting property of 2H-MoS2, where the charge transfer efficacy is restricted by an insufficiency of electrons at the chemical interface (Voiry, 2016; Li, 2015). Secondly, switching the MoS2 phase from 2H to 1T, which is more conductive and thus more catalytically active (Kan, 2014; Lukowski, 2013). The active sites in 1T–MoS2 are the S atoms in the basal plane; however, despite the substantially increased site density, these S sites have less acceptable hydrogen adsorption properties (GH = 0.17 eV) (Peng et al., 2021). Aside from these issues with 2H-MoS2 and 1T–MoS2, one big challenge with both of these substances have poor stability, since defective 2H-MoS2 has a high sulfur leaching rate and 1T–MoS2 is intrinsically metastable (Longfei and Jan 2021; Geng, 2016). MoS2 appears to be widely applicable to the HER only when the electrical conductivity, site density, inherent activity, and stability concerns are all addressed at the same time. Owing to lower hydrogen adsorption energy of Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) compared to noble metals (among which Pt is one), indicating that MoS2-based materials have a lot of potential as a replacement for Pt in the HER (Yan et al., 2014; Yipeng et al., 2019). The catalytic efficiency of MoS2 could be improved even further by doping and/or substituting heteroatoms to lower the energy of hydrogen adsorption and modify the orbital structure of the valence and conduction bands, according to theoretical research (Zheng et al., 2015; Zexing et al., 2020). According to current study, doping MoS2 with palladium (Pd) or transition metals like zinc (Zn) has been shown to boost HER activity (Song et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2019). Since it is commonly known, Pd and Mo have similar atomic radii. Therefore, we chose the element Pd as a dopant atom to examine its effects on MoS2 based on the aforementioned concepts (see Table 1 and 2).

Composition

Average Crystallite Size “D” (nm)

Pure MoS2

78.719

Pd-MoS2-1 wt%

124.747

Pd-MoS2-2 wt%

453.116

Catalyst

Electrolytes

Overpotential (mv vs.RHE) @100 mA/cm2

reference

2 wt%Pd-MoS2

0.5 M H2SO4

119

This work

Se-MoS2/Co0.2Ni0.8Se2

Universal pH

122

2

Col-Fel-B

1 M KOH

355

4

MoP@PC

0.5 M H2SO4

>200

7

MoS2NFs/rGO

0.5 M H2SO4

>400

8

MoS2-40

0.5 M H2SO4

>200

9

1 T- MoS2

0.5 M H2SO4

>200

18

M- MoS2

0.5 M H2SO4

>300

19

N-WS2/Ni3FeN

1 M KOH

140

37

MoS2/rGO/NiS-5

1 M KOH

212

36

With the aforementioned background, this project aimed to synthesize Pd-MoS2 nanorods (1&2 wt%) using one-pot solvo-thermal approach and the subsequent optimized electrochemical activity of Pd-MoS2 for hydrogen evolution reaction.

2 Experimental section

The detail of materials used and fabrication of pure MoS2 nanorods and Pd doped MoS2 is described in detail below.

2.1 Materials

This experiment employed only analytical-grade chemical reagents. Molybdenum (VI) dioxide bis (acetylacetonate) [MoO2 (acac)2] and oleylamine (OAm, 70%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Dibenzyl disulfide [(PhCH2)2Se2, 95%] was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Absolute ethanol and toluene were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Ltd. All chemicals were used in the experiments without further purification.

2.2 Preparation of MoS2 nanorods

In a typical synthesis, 0.5 mmol of Molybdenum (VI) dioxide bis (acetylacetonate) [MoO2 (acac)2] and 0.5 mmol Dibenzyl disulfide [(PhCH2)2S2] were dispersed in 10 mL of olylamine (OAm) using ultra-sonication for 30 min. After mixing well, 0.05 mg of Borane tert-butylamine (BTB) was added to the mixture of MoO2 (acac)2 and (PhCH2)2S2 then ultrasonicate further for 10 min. The above-mentioned mixture was autoclaved for 12 h at 280 °C in a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. The as-obtained product was centrifuged at 7000 rpm and washed with toluene 6 times before being dried in a vacuum oven at 70 °C for 3 h.

2.3 Preparation of Pd-MoS2 nanorods

The synthesis technique for Pd-MoS2 is the same as for MoS2, with the exception that Pd (acac)2 solution (1 wt% Pd in OAM) was used as per the specified MoS2: Pd mass ratio. Similarly, another sample was prepared by adding 2 wt% Pd solution into the mixture of MoO2 (acac)2 and (PhCH2)2S2.

3 Characterizations

3.1 Physical characterization

The as-obtained products were characterized using variety of techniques. A Philips X'pert PRO X-ray diffractometer with Cu K, λ = 1.54182 Å, a JSM-6700F, and a Hitachi H-7650 for SEM and TEM, correspondingly, were used to investigate the structure and surface morphology of the MoS2 nanorods and Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% and 2 wt%). The elemental composition and oxidation number of the composite elements were investigated using an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) VGESCA-LAB MKII X-ray photoelectron spectrometer with Mg as the excitation source. At ambient temperature, a JYLABRAM-HR Confocal Laser Micro-Raman spectrometer was used to examine the Raman spectra using a 514.5 nm argon laser.

3.2 Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed in a three-electreode system on a CHI660E electrochemical workstation, using an Ag/AgCl (in saturated KCl sulution) electrode as the reference electrode and a graphite rod as the counter electrode. The following is how the working electrodes were managed to make: To begin, 5 mg of annealed catalyst (at 350 °C for 2 h in an inert environment) was dispersed in 1 mL of ethanol, and 40 L of catalyst ink was drop-cast onto carbon paper (0.5 0.25 cm2), then dried in a 70 °C oven. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves were obtained from 0 to −0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl electrode in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution at a scan rate of 5 mV/S and the cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were tested under the same condition except the scan rate was 50 mV/s. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic (EIS) tests were taken at potential −0.35 V at frequency ranging from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz. For stability purpose, samples were continuously cycled for 1000 and 3000 cycles. Electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was estimated by calculating Cdl ( vs different scan rates) in non-faradic potential range 0.33–0.43 V.

4 Result and discussion

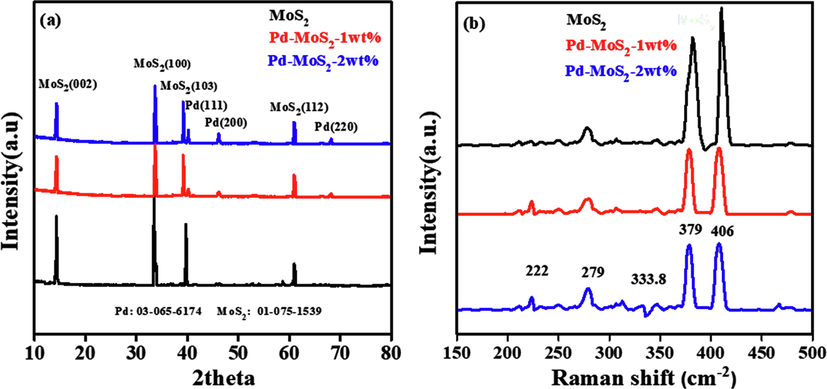

The crystallinity and phase study of pure MoS2 and Pd doped MoS2 nanorods (1 wt% & 2 wt%) were demonstrated using XRD technique. Each 1 wt% Pd-MoS2 and 2 wt% Pd-MoS2 have a set of distinctive peaks at 40.7°,46.6°, and 68.1°, which correspond to the (1 1 1), (2 0 0), and (2 2 0) planes of the conventional fcc (face-centered-cubic) Pd crystalline structure, respectively (card # 03-065-6174) (Santra et al., 2013). In addition to the peaks for Pd, other peaks in the XRD pattern of Pd-MoS2 that are simultaneously indexed to MoS2 (0 0 2), (1 0 0), (1 0 3), and (1 1 2) demonstrate the effective doping of Pd on MoS2 (card # 01-075-1539). Moreover, the XRD pattern of pure MoS2 only demonstrate the peaks for its hexagonal phase planes (Zhong et al., 2019; Iqbal et al., 2020). Scherer’s formula is used to compute the crystalline size of the manufactured MoS2 nanostructures.

Raman spectroscopy is an effective tool that can detect material thickness, crystallographic orientation and phase transition. The comparative Raman spectra of as-grown MoS2 nanorods and Pd-MoS2 ((1 wt% & 2 wt%) are shown in Fig. 1b. The pure MoS2 nanorods display two distinct Raman peaks, the E12g mode at 379 cm−1 and the A1g mode at 410 cm−1, as shown in the figure. These findings are in agreement with previous studies (Late et al., 2014). The deposition of Pd atoms in nanorods causes an apparent red shift of around 4.0 cm−1 of the A1g peak, whereas the position of the E12g peak nearly remains unchanged. As a consequence, the difference (

) between both the E12g and A1g peaks in pure MoS2 nanorods drops from 31.0 to 27.0 cm−1 in Pd-MoS2 nanorods (1 wt% & 2 wt%) (Lin et al., 2014). As a result, this demonstrates that Pd doping can produce a considerable modification in the electronic structure of MoS2 nanorods. Furthermore, the two new weak peaks found in Raman spectra of Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% & 2 wt%) at 222 cm−1 and 33.8 cm−1, which are coincided with the 1T phase molybdenum disulfide, could be attributed to modifications in the material's structure. The weak peak at 283 cm−1 belong to E1g ([33]).

(a) XRD pattern of MoS2, Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% &2 wt%), (b). Raman spectra of MoS2, Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% & 2 wt%).

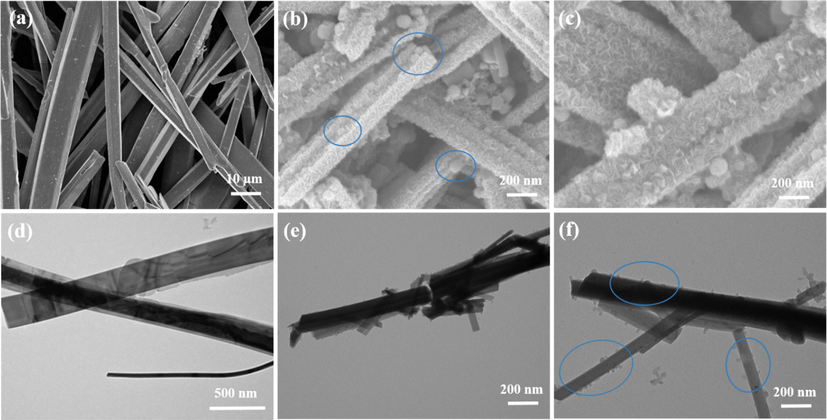

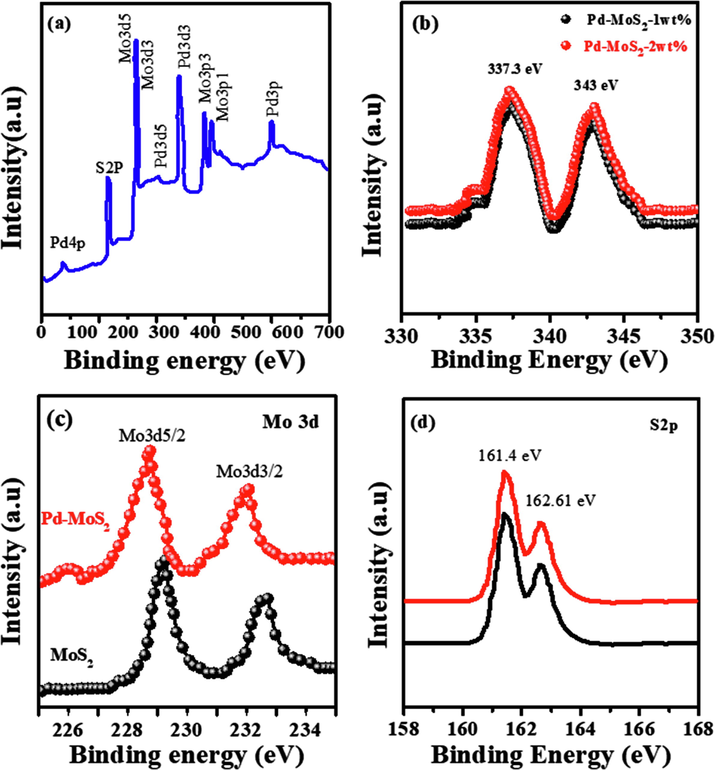

In Fig. 2, SEM and TEM micrographs were used to examine the microstructure and morphology of MoS2 nanorods and Pd-MoS2. SEM and TEM images of pure MoS2 nanorods revealed rod-like morphology, as illustrated in Fig. 2a and 2d. The numerous tiny Pd NPs distributed over the substrate on MoS2 nanorods for Pd-MoS2 (1 wt%) are clearly visible in SEM and TEM micrographs (Fig. 2b and e). More intriguingly, as demonstrated in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image Fig. 2f, apparent Pd particles were regularly produced on the MoS2 nanorods. Micrographs of the Pd-MoS2 (2 wt%) nanorods using scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 2c) and transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2f) reveal that Pd particles are uniformly adorned on the surfaces, as seen in the images encircled. The characteristic XPS spectrum of Pd-MoS2 nanorods is shown in Fig. 3a, demonstrating the coexistence of Pd, Mo, and S. Pd element binding energies in the Pd doped MoS2 nanorods are shown in Fig. 3b. Two distinctive peaks at 337.3 eV and 343.0 eV are attributed to Pd 3d5/2 and 3d3/2, correspondingly. The binding energies are substantially higher than those of Pd metals, and they are strikingly similar to those of Pd4+ (Yuwen et al., 2014; Hao et al., 2015). This implies that Mo atoms have been successfully replaced by Pd dopants, and that the Pd atoms have been covalently stabilized inside the lattice. Fig. 3c and d typically demonstrate high resolution XPS spectra of Mo 3d and S 2p. The binding energies of Mo and S for the MoS2 nanorods without Pd doping are depicted in black curves. The Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 orbitals are ascribed to the peaks at 229.2 and 232.6 eV, correspondingly. When compared to the pure MoS2 nanorods, the fundamental peaks of Mo in the Pd-MoS2 nanorods reveal a smooth change toward lower binding energies, as seen in the figure. This shift could be explained by a decrease in Fermi level (EF) as a result of p type doping, as previously seen in other research (McDonnell et al., 2014). The binding energies of the S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2 emerge at 163.5 and 162.2 eV, correspondingly, and there is essentially no change between the nanorods with and without Pd doping.

(a) SEM image of MoS2 nanorods (b &c) SEM images of Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% & 2 wt%), (d) TEM image of MoS2 (e, f) TEM image of Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% &2 wt%).

(a) XPS survey scan of Pd-MoS2 nanorods, (b) Pd 3d (c) Mo 3d (black for MoS2 nanotube and red for Pd-MoS2 2 wt%), (d) S2p (black for MoS2 nanotube and red for Pd-MoS2 2 wt%).

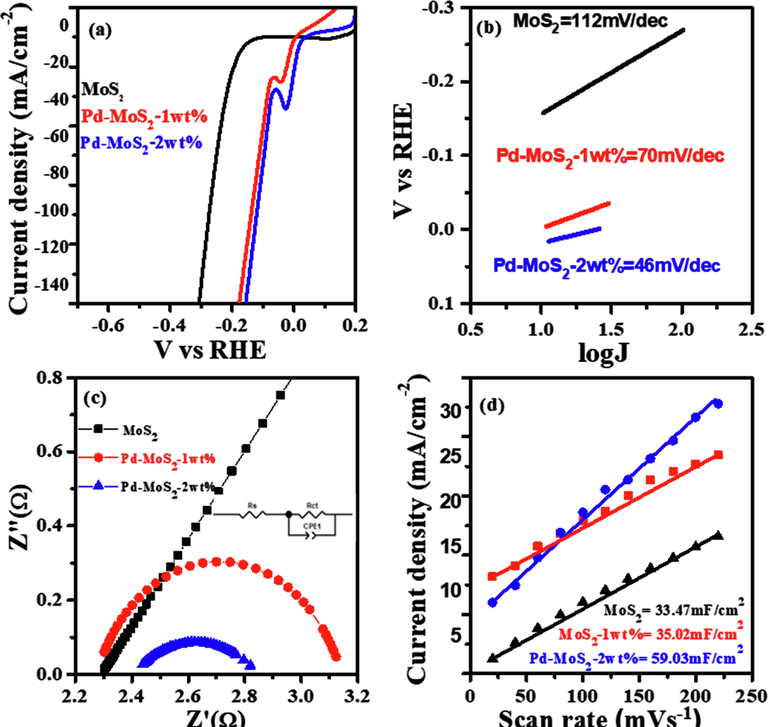

The HER catalytic behavior of MoS2 and Pd-MoS2 was investigated using the demonstrative linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) shown in Fig. 4a. The electrode with pure MoS2 exhibited the lowest catalytic activity in acidic medium, which can be seen in Fig. 4a. Both the 1 wt% and 2 wt% Pd-MoS2 samples displayed increased catalytic activity and lower overpotential when compared to pristine MoS2. Initially, the pristine MoS2 had a current density of 100 mA/cm2 at 273 mV, which was analogous to prior MoS2/rGO/NiS observations (Guangsheng et al., 2021). Secondly, 1 Wt% Pd doping on MoS2 (η@100 mA cm−2 = 137 mV) further improve the activity. Further, Pd doping led to a dramatic improvement in catalytic performance toward the HER, which considerably outperforms 1% Pd-MoS2 and pure MoS2 catalysts. The 2 Wt% Pd–MoS2 catalyst displayed a current density of 100 mA/cm2 at an overpotential of only 119 mV, which is significantly better than that of hetero-structured tungsten-based catalysts (Jinsong et al., 2022). This is the best performance ever for heteroatom-doped MoS2-based catalysts in acidic media (Zhilong et al., 2020; Luozhen et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018). Tafel slope is key descriptor to evaluate the kinetics of HER. The Tafel slope was used to assess the kinetic behaviour of the Pd-MoS2 nanorods for HER. As shown in Fig. 4b, the Tafel slope of 2 Wt% Pd-MoS2 nanorods is 48 mV/dec, which is lower than 1 Wt% Pd-MoS2 (70MmV/dec), MoS2 nanorods (112 mV/dec) and the majority of previously described MoS2-based HER electrocatalysts implying that Pd-MoS2 nanorods has better reaction kinetics in the HER process (Zheng et al., 2018; Meng, 2020). The Tafel slope indicated a gradual drop from 112 mV/dec to 70–48 mV/dec, demonstrating that these materials have HER kinetics based upon Heyrovsky reaction, which is the rate-determining step in electrochemical desorption (Jung et al., 2017; Jue et al., 2019).

(a) Polarization curves of pure MoS2 nanorods, Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% & 2 wt%), (b) Tafel slopes (c) Nyquist plot (d) Double layer capacitance recorded in non-faradic area of successive LSVs.

Moreover, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements at −350 mV vs reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz were performed to better investigate electrode kinetics during the HER process. Fig. 4c illustrates the Nyquist plots of these electrodes and the fitted equivalent circuit in the inset. The smaller and larger semicircles indicate the electrode–electrolyte interface resistance and the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the H+ reaction, respectively (Luo et al., 2018). As demonstrated in Fig. 4c, when compared to pure MoS2 nanorods, the charge-transfer resistances drop significantly, with 1 Wt% Pd-MoS2 (1.05) and 2 Wt% Pd-MoS2 (0.4) having the lowest Rct values. These findings suggest that a significant concentration of Pd doping can greatly enhance conductivity and charge transfer, hence boosting reaction efficiency. To gain a better understanding of these electrocatalysts, the electrochemical surface area (ECSA) values were examined. The electrochemical double layer capacitances (Cdl) were calculated using conventional CV, and the typical CV curves recorded for the different catalyst with variable scan rates are presented in Fig d (Fengming et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Miguel et al., 2015). In this scenario, a greater Cdl value indicates a higher ECSA. The Cdl of the 2 Wt% Pd-MoS2 catalyst was approximately 59.03 mF cm2, substantially higher than that of the 1 Wt% Pd-MoS2 (35.02 mF cm2) and pure MoS2 (33.47 mF cm−2 as indicated in Fig. 4d. This result underpinned the effective synthesis of the Pd-MoS2 catalyst, in which the 2Wt % doping of Pd on MoS2 nanorods exposed more active sites 1 Wt% Pd-MoS2 and pure MoS2 nanorods. The Pd doped MoS2 catalyst's HER performance was improved as a result of its efficient surface charge transfer, faster reaction rate, and large ECSA.

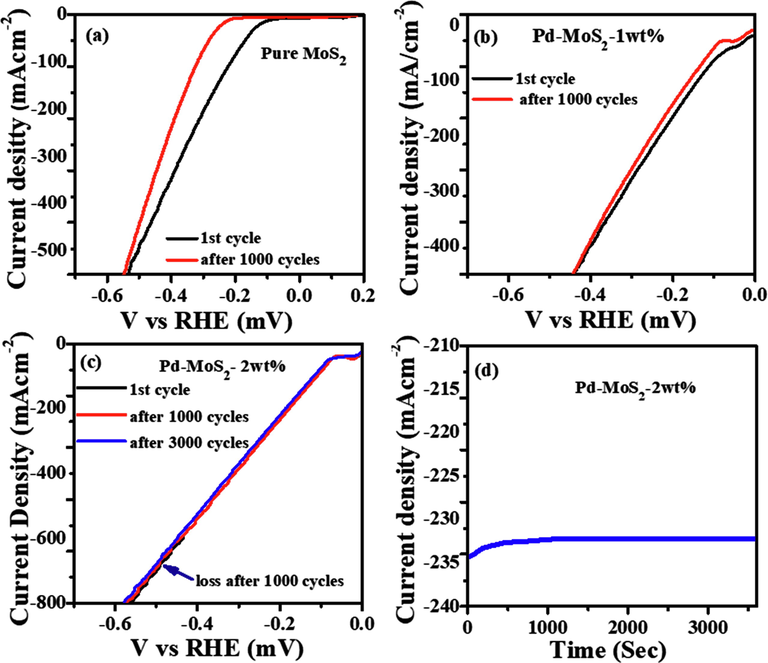

We are concerned about the catalyst's electrochemical stability because the hydrogen generating process could result in structural deformation and activity loss with continuous cycling (Ying et al., 2021; Zhijuan et al., November 2021). The electrocatalytic stability of Pd-MoS2 nanorods was investigated by comparing LSV curves before and after cyclic voltammetry test (1000 cycle and even 3000 cycles for 2 wt% Pd-MoS2) in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. After 3000 cycles, the polarization curve shows no apparent change, as illustrated in Fig. 5c. Under the same experimental conditions, however, the HER stability of the pure MoS2 nanorods as well as 1 wt% Pd-MoS2 electrocatalysts (after 1000Cv cycles) is relatively poor. In electrocatalysis, durability is essential since the commercial electrode would have to be able to maintain a constant current for an extended period of time. To assess the durability, galvanostatic measurements were taken at potential of −0.4 V and the result (Fig. 5d) demonstrated that Pd-MoS2 operated well after 10 h of continuous operation.

(a) Stability tests for the first LSV curve and one after 1000 CV cycles for MoS2 nanorodes (b, c) Pd-MoS2 (1 wt% and 2 wt% (upto 3000 Cv cycles)) (d) Time dependent i-t curves at −0.4 V.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, using a facile solvo-thermal route, we were able to successfully fabricate Pd-MoS2 electrocatalyst with precise composition (doping) and morphologies (nanoparticles on nanorods). Ultimately, we discovered a catalyst for the HER in acidic conditions that has superior catalytic activity, increased conductivity, high surface area, and long-term durability. This research could pave the way for more logical design of cost-effective and high-performance hydrogen evolution catalysts.

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science of china (Nos. and) and Anhui Provincial Natural Science (No.). Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/241) Taif University, Taif Saudi Arabia.

References

- Ionic liquid as reaction medium for synthesis of hierarchically structured one-dimensional MoO2 for efficient hydrogen evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(8):7217-7223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Large-current-stable bifunctional nanoporous Ferich nitride electrocatalysts for highly efficient overall water and urea splitting†. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:10199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pure and stable metallic phase molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun.. 2016;7:10672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defect-rich heterogeneous MoS2/rGO/NiS nanocomposite for efficient pH-universal hydrogen evolution. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:662.

- [Google Scholar]

- L. Z. Hao, W. Gao,b Y. J. Liu, Y. M. Liu, Z. D. Han, Q. Z. Xue and J. Zhuc, Self-Powered Broadband, High-Detectivity and Ultrafast Photodetectors Based on Pd-MoS2/Si Heterojunctions, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 00, 1-3 (2015).

- Biornimetic hydrogen evolution: MoS2 nanoparticles as catalyst for hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2005;127:5308-5309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of optical constants of sputtered MoS2 and MoS2/Al2O3 composite thin films. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron.. 2020;31:7753-7759.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of active edge sites for electrochemical H2 evolution from MoS2 nanocatalysts. Science. 2007;317:100-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Robust hydrogen-evolving electrocatalyst from heterogeneous molybdenum disulfide-based catalyst. ACS Catal.. 2020;10:1511-1519.

- [Google Scholar]

- Boosting alkaline hydrogen and oxygen evolution kinetic process of tungsten disulfide-based heterostructures by multi-site engineering. Boosting Alkaline Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution Kinetic Process of Tungsten Disulfide-Based Heterostructures by Multi-Site Engineering.. 2022;18(1):2104624.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetic-oriented construction of MoS2 synergistic interface to boost pH-universal hydrogen evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2019;30(6):1908520.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic synergy effect of MoS2/reduced graphene oxide hybrids for a highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. RSC Adv.. 2017;7:5480.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structures and phase transition of a MoS2 monolayer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:1515-1522.

- [Google Scholar]

- A molecular MoS2 edge site mimic for catalytic hydrogen generation. Science. 2012;335:698-702.

- [Google Scholar]

- Engineering the surface structure of MoS2 to preferentially expose active edge sites for electrocatalysis. Nat. Mater.. 2012;11:963-969.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulsed laser-deposited MoS2 thin films on W and Si: field emission and photoresponse studies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:15881.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optoelectronic crystal of artificial atoms in strain-textured molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun.. 2015;6:7381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly active non-noble electrocatalyst from Co2P/Ni2P nanohybrids for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Today Phys.. 2020;16:100314

- [Google Scholar]

- Boosting pH-universal hydrogen evolution of molybdenum disulfide particles by interfacial engineering. Chin. J. Chem.. 2019;37:288-294.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly robust non-noble alkaline hydrogen-evolving electrocatalyst from Se-doped molybdenum disulfide particles on interwoven CoSe2 nanowire arrays. Small. 2020;16(13):1906629.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electron-doping-enhanced trion formation in monolayer molybdenum disulfide functionalized with cesium carbonate. ACS Nano. 2014;8:5323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longfei, W., Hofmann, Jan P., 2021. Comparing the Intrinsic HER Activity of Transition Metal Dichalcogenides: Pitfalls and Suggestions ACS Energy Lett. 6 (2021) 2619–2625.

- Enhanced hydrogen evolution catalysis from chemically exfoliated metallic MoS2 nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2013;135:10274-10277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemically activating MoS2 via spontaneous atomic palladium interfacial doping towards efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun.. 2018;9:2120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Luozhen, B., Wei, G., Jiamin, S., Mingming, H., Fulin, L., Zhaofeng, G., Lei, S., Ning, H., Zai-xia, Y., Aimin, S., Yongquan, Q., Johnny, C.H., 2018. Phosphorus doped MoS2 nanosheets supported on carbon cloths as efficient hydrogen generation electrocatalysts, Chem. Cat. Chem. 10, 1571-1577 (2018).

- MoS2 nanoflower-decorated reduced graphene oxide paper for high-performance hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale. 2014;6:5624-5629.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent modification strategies of MoS2 for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Molecules. 2020;25:1136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis using ternary pyrite-type cobalt phosphosulphide. Nature. Mater.. 2015;14(12):1245-1251.

- [Google Scholar]

- 1T-MoS2 coordinated bimetal atoms as active centers to facilitate hydrogen generation. Materials. 2021;14:4073.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palladium Nanoparticles on graphite oxide: a recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of biaryl cores. ACS Catal.. 2013;3:2776-2789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science. 2017;355 eaad4998

- [Google Scholar]

- A palladium doped 1T-phase molybdenum disulfide-black phosphorene two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructure for visible-light enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nanoscale. 2021;13:5892-5900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeted bottom-up synthesis of 1T-phase MoS2 arrays with high electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity by simultaneous structure and morphology engineering. Nano Res.. 2018;11:4368-4379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical generation of sulfur vacancies in the basal plane of MoS2 for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun.. 2017;8:15113.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of electronic coupling between substrate and 2D MoS2 nanosheets in electrocatalytic production of hydrogen. Nat. Mater.. 2016;15:1003-1009.

- [Google Scholar]

- Activation of MoS2 Basal planes for hydrogen evolution by zinc. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.. 2019;58:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent development of molybdenum sulfides as advanced electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catalysis. 2014;4:1693-1705.

- [Google Scholar]

- Porous molybdenum phosphide nano-octahedrons derived from confined phosphorization in UIO-66 for efficient hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2016;55:12854.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trifle Pt coupled with NiFe hydroxide synthesized via corrosion engineering to boost the cleavage of water molecule for alkaline water-splitting. Appl. Catal. B. 2021;297:120395

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuning orbital orientation endows molybdenum disulfide with exceptional alkaline hydrogen evolution capability. Nat. Commun.. 2019;10:1217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yixin Yao, Kelong Ao, Pengfei Lv and Qufu Wei, MoS2 Coexisting in 1T and 2H Phases Synthesized by Common Hydrothermal Method for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction, Nanomaterials (Basel) 9, 844 (2019).

- General synthesis of noble metal (Au, Ag, Pd, Pt) nanocrystal modified MoS2 nanosheets and the enhanced catalytic activity of Pd–MoS2 for methanol oxidation. Nanoscale. 2014;6:5762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of Co-Fe-B-P nanochains as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water-splitting. Nanoscale. 2012;00:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent progress of vacancy engineering for electrochemical energy conversion related applications. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2020;31(9):2009070.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion Engineering on iron foam toward efficiently electrocatalytic overall water splitting powered by sustainable energy. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2021;31:2010437.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advancing the electrochemistry of the hydrogen-evolution reaction through combining experiment and theory. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.. 2015;54:52-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- The hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline solution: from theory, single crystal models, to practical electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.. 2018;57:7568-7579.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface carbon layer controllable Ni3Fe particles confined in hierarchical N-doped carbon framework boosting oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Powd. Mater.. 2021;23

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boosting hydrogen evolution on MoS2 via co-confining selenium in surface and cobalt in inner layer. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-dimensional MoS2/graphene aerogel as binder-free electrode for Li-ion battery. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2019;14:85.

- [Google Scholar]