Translate this page into:

An unexpectedly stable Y2B5 compound with the fractional stoichiometry under ambient pressure

⁎Corresponding author. zcz19870517@163.com (Chuanzhao Zhang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Boron-rich yttrium borides are an exceptional group of compounds not only with excellent mechanical properties, but also with particular superconducting and thermoelectric properties. Although the Y–B compounds with integral components have been extensively investigated experimentally and theoretically, the yttrium borides with the fractional stoichiometries are rarely observed. Herein, utilizing a combination of the CALYPSO method for crystal structure prediction and first-principles calculations, we made an investigation on a broad range of stoichiometries of yttrium borides. An extraordinary stable Y2B5 compound possessing the fractional stoichiometry with the monoclinic P121/c1 phase is firstly uncovered. Structurally, the P121/c1-Y2B5 crystalline consists of the distorted B6 octahedrons and seven-member B rings. Remarkably, the B–B covalent network following the increment of the boron content in six concerned yttrium borides undergoes an increasing dimension, quasi one-dimensional chain → two-dimensional B ring → a combination of two-dimensional B ring and three-dimensional B6 octahedron → three-dimensional B24 cage. According to a microscopic hardness model, P121/c1–Y2B5 is considered as an incompressible and hard material with the hardness of 18.83 GPa. More importantly, Fm-3 m-YB12 can be classified into an ultra-incompressible material with the appreciable Vickers hardness of 33.16 GPa. The present consequences can provide important insights for understanding the complex crystal structures of boron-rich yttrium borides and stimulate further experimental synthesis of novel multifunctional materials with the fractional compositions.

Keywords

Transition-metal borides

First-principles calculation

Fractional stoichiometry

Structural characteristics

Vickers hardness

1 Introduction

In the past decades, transition-metal borides (TMBs) have attracted widespread attention because of the high hardness, ultra-compressibility, high melting points, excellent thermal stability and superior electrical properties (Ma et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2019; Jothi et al., 2018; Levine et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). These highlighted properties make them possess a wide range of applications, for instance, in cutting and polishing tools, coating materials, abrasives, etc (Gu et al., 2021; Cumberland et al., 2005). Among these TMBs, boron rich compounds, have received a lot of attention and are regarded as the potential superhard materials such as ReB2 (48 GPa by 0.49 N) (Chung et al., 2007), OsB2 (37 GPa) (Weinberger et al., 2009), CrB4 (48 GPa) (Niu et al., 2012), WB4 (43 GPa) (Mohammadi et al., 2011), MnB4 (35–37 GPa) (Gou et al., 2014) and FeB4 (62 GPa) (Gou et al., 2013). However, access to boron-rich TMBs with high hardness just by exploring the borides with the integral ratios of B/TM is limited. Thereby, much effort has been devoted to the investigation of the boron-rich TMBs having the fractional stoichiometries. Two promising superhard compounds, IrB1.1 and RhB1.1 (Latini et al., 2010); experimentally fabricated by applying the pulsed laser deposition technique, have the extraordinarily high hardness values of 43 and 44 GPa, respectively. Subsequent theoretical investigations have further demonstrated that Nb2B3 is a superior hard material with a hardness value of 33.5 GPa (Pan and Lin, 2015). Meanwhile, Li et al. unveiled two fractional stoichiometries in the Ti–B system, Ti3B4 and Ti2B3, which possess the calculated hardness values of 32.2 and 33.7 GPa (Li et al., 2015). Recently, W2B3 with the P21/m symmetry and W2B5 having the R3m phase, have been calculated to exhibit the latent ultra-incompressibility with the Vickers hardness values of 31.7 and 36.5 GPa (Zhao et al., 2018). In view of the above descriptions, the boron-rich TMBs with fractional stoichiometries play an important role in designing superhard materials. In consequence, to better disclose more boron-rich TMBs with superhard character, it is earnestly needed to study probe into the boron-rich TMBs not only with the integral ratios but also with the fractional stoichiometries.

The yttrium borides are probably the technologically most important binary system among the transition metal borides. The boron-rich compounds in the Y–B binary system exhibit particular superconducting properties (Xu et al., 2007; Lortz et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2018) and have been considered to be attractive candidates as high temperature thermoelectric materials (Hossain et al., 2015; Sauerschnig et al., 2020). On account of the outstanding properties of boron-rich yttrium borides and their applications in various fields, great efforts have been devoted to probe into them both experimentally and theoretically. So far, five different stoichiometric compositions in the Y–B binary system (YB2, YB4, YB6, YB12, and YB66) have been confirmed from experimental measurements (Liao and Spear, 1995). The YB2 compound crystallizes into the AlB2-type structure with space group of P6/mmm, which is classified into the hexagonal crystalline system. Song and co-workers (Song et al., 2001) revealed that YB2 is a paramagnetic compound and the temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility obeys excellently the Curie-Weiss law above 20 K. For the YB4 compound, the previous investigations (Villars and Cenzual, 2007; Jäger et al., 2004; Waškowska et al., 2011) uncovered that it has a tetragonal P4/mbm configuration with the high bulk moduli (185 GPa). YB6 was proposed to possess the cubic Pm-3 m phase under ambient pressure, which is similar to CaB6 (Xu et al., 2007; Lortz et al., 2006; Liao and Spear, 1995). Moreover, previous first-principles calculations demonstrated that the most stable phase undergoes a high-pressure phase transition with the transition order of Pm-3 m → Cmmm → I4/mmm with the corresponding transformation pressures of 3.2 and 35.8 GPa (Wang et al., 2018). Very recently, Ding et al. discovered a novel R-3 m structure of YB6, which is more stable than the experimentally synthesized Pm-3 m phase, with a considerable hardness of 37 GPa (Ding et al., 2021). Consensus has been reached on that the YB12 (Shein and Ivanovskĭ, 2003; Czopnik et al., 2005) and YB66 (Seybolt, 1960; Richards and Kaspar, 1969; Oliver and Brower, 1971; Günster et al., 1998; Mori and Tanaka, 2006) compounds adopt the cubic Fm-3 m and Fm-3c phases, respectively. Besides the aforementioned five Y–B compounds, the other boron-rich yttrium borides-YB25 (Tanaka et al., 1997), YB48 (Hossain et al., 2015), YB56 (Higashi et al., 1997; Oku et al., 1998), and YB62 (Higashi et al., 1997), have also been studied in experiment. However, up to now, few studies have been focused on the crystalline structures of yttrium borides with fractional stoichiometric ratios. Therefore, we aim to corroborate whether there are stable structures with the fractional stoichiometries in the binary Y–B compounds. On the other hand, the rich phase diagram arises another issue: are there novel stable phases of Y–B crystals with unpredictable physical properties could not be uncovered in the preceding research? Consequently, these doubts inspire us to explore whether other stoichiometries of yttrium borides on the boron-rich side could be stable under ambient pressure, especially for the Y–B compounds with the fractional compositions.

In the present work, we comprehensively probe into the stable and metastable phases of yttrium borides with eleven stoichiometries based on an unbiased CALYPSO structural search method in conjunction with first-principles calculations under pressure of 1 atm. In addition, the structural features, mechanical properties, chemical bonding and hardness of typical stable yttrium borides are also systematically predicted. Four experimentally fabricated structures (YB2, YB4, YB6, and YB12) (Song et al., 2001; Jäger et al., 2004; Czopnik et al., 2005) have been successfully reproduced, which substantiate the reasonability of our structure search methodology. Notably, a novel Y2B5 compound containing the fractional component with the monoclinic P121/c1 structure is firstly discovered under atmospheric pressure. This P121/c1-Y2B5 phase possesses the distorted B6 octahedrons and seven-member B rings. More importantly, as the B content increases, the B–B covalent network exhibits an increasing dimension, namely, quasi one-dimensional chain → two-dimensional B ring → a combination of two-dimensional B ring and three-dimensional B6 octahedron → three-dimensional B24 cage. This phenomenon is firstly uncovered in six considered yttrium borides (YB, YB2, Y2B5, YB4, YB6 and YB12). The P121/c1-Y2B5 phase is observed to be an incompressible and hard material with the hardness of 18.83 GPa. More importantly, the Fm-3 m-YB12 structure can be regarded as an ultra-incompressible material with a considerable Vickers hardness of 33.16 GPa.

2 Computational methods

To intensively obtain the stable and metastable crystalline structures of yttrium borides with a variety of compositions (YmBn, m/n = 2/1, 3/2, 1/1, 3/4, 2/3, 1/2, 2/5, 1/3, 1/4, 1/6, and 1/12), we carried out an unbiased structure prediction on the basis of the particle swarm optimization algorithm as implemented in the CALYPSO code (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). This methodology is effectively capable of discovering the stable or metastable phases only relying on the given components, which has been corroborated with the successfully predicted examples from element solid to binary and ternary systems under ambient and high pressures (Lv et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2020; Jin et al. n.d.; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). The structure predictions were conducted using simulation cells containing up to four formula units (f.u.) at atmospheric pressure. The detailed description on this search algorithm can be found in the related literatures (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012).

The subsequent structural optimizations and electronic structure calculations were performed based on density functional theory within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of the Perdew − Burke − Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange–correlation functional, as executed in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) (Kresse and Furthmüller, 1996; Perdew et al., 1996). Plane-wave basis sets and the projector augmented wave (PAW) method were applied to describe the electron–ion interactions with 4s24p65s24d1 and 2s22p1 regarded as valence electrons for Y and B atoms, respectively (Kresse and Joubert, 1999). A kinetic cutoff energy of 800 eV for the expansion of the wave function into plane waves and proper Monkhorst − Pack k-meshes were selected to insure that all the enthalpy calculations were well converged within 1 meV/atom (Monkhorst and Pack, 1976). The formation energy (ΔG), relative to the elemental solids (hexagonal α-Y and rhombohedral α-B with space groups of P63/mmc and R-3 m, respectively) (Spedding et al., 1961; Decker and Kasper, 1959), was estimated at atmospheric pressure on the basis of the equation below:

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Convex hull and phase stability

In the first step, structure searches of solid yttrium and boron were implemented under atmospheric pressure. Remarkably, the well-known hexagonal α-Y (P63/mmc) (Spedding et al., 1961) and rhombohedral α-B (R-3 m) (Decker and Kasper, 1959) phases observed in experiments for solid yttrium and boron were successfully reproduced within the CALYPSO methodology, confirming the feasibility of our calculations. A following structure prediction on the Y–B compounds with eleven components (Y2B, Y3B2, YB, Y3B4, Y2B3, YB2, Y2B5, YB3, YB4, YB6, YB12) was made by utilizing the CALYPSO method in combination with first-principles method at ambient pressure. The phase stability at 0 K can be judged based on the formation enthalpy per atom in YmBn, which can be calculated as follows:

Here, ΔH is the relative formation enthalpy per atom for the yttrium boride with the YmBn composition and E (YmBn) is the total energy per formula unit of this compound. Moreover, E (Solid Y) and E (Solid B) denote the equilibrium enthalpies of each Y and B atom situated in the respective ground state (Spedding et al., 1961; Decker and Kasper, 1959). On the basis of the above formula, the lowest enthalpy structures of each above components in the Y–B binary system were further confirmed, whose crystal structures are depicted in Fig. S1 of the supplementary information with the corresponding structural information summarized in Table S1.

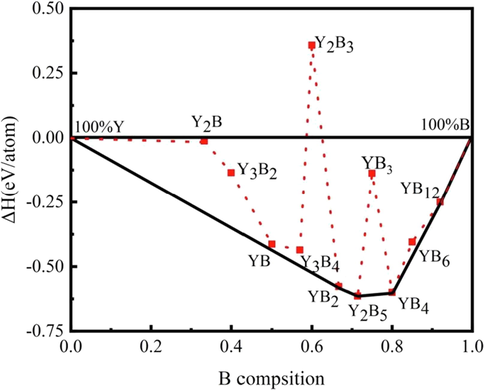

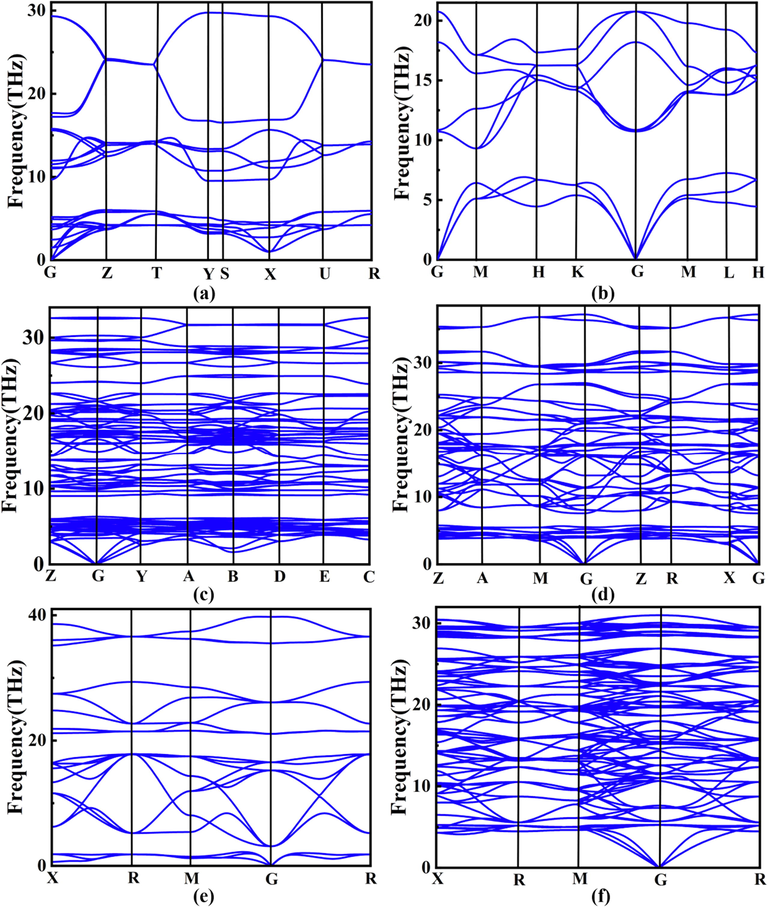

To verify the relative stability of the lowest enthalpy structures of each composition in the Y–B binary system, the convex hull of the Y–B system at 0 K under ambient pressure is constructed in Fig. 1. In addition, the lattice parameters, a, b and c, cell volume per formula unit V, total enthalpies per formula unit H and formation enthalpies per atom ΔH for the lowest formation enthalpy of each compositions of the Y − B binary system are summarized in Table S2. Any phase whose formation enthalpy located exactly on the convex hull is considered as energetically stable, both against decomposition into the elements and into any combination of other binary compounds, and thus synthesizable in principle experimentally (Ghosh and A.van de Walle, M. Asta, , 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). As displayed in Fig. 1, only four compounds sit exactly right on the curves of the convex hull, namely, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4 and Fm–3 m-YB12, declaring that they are thermodynamically stable. Among them, P6/mmm-YB2, P4/mbm-YB4 and Fm–3 m-YB12 have been already fabricated in the laboratory (Song et al., 2001; Jäger et al., 2004; Czopnik et al., 2005); nevertheless, the Y2B5 compound with the monoclinic P121/c1 configuration is a novel ground-state form acquired within our structure search calculations. More importantly, this new structure is a thermodynamically stable phase and possesses an unprecedentedly fractional stoichiometry in the Y–B binary system. Aside from the aforementioned four stable components lying on the convex hull, we also focus on the low-enthalpy metastable phases, which are situated marginally above the convex hull lines. From Fig. 1, the Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6 structures lie above the convex hull by 14 and 17 meV, respectively, which illustrates both compounds could be synthesized under particular temperature and pressure conditions. To further evaluate the thermal contributions to the formation free energy, we constructed the convex hull of the Y–B system under ambient pressure at the temperatures of 300, 1000 and 2000 K, along with that at 0 K, as summarized in Fig. S2. At 300 and 1000 K, the stable compounds are also P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4 and Fm–3 m-YB12. Additionally, the Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6 structures also slightly lie above the convex hull. Therefore, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4 and Fm–3 m-YB12 are stable and Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6 should be classified into metastable phases under ambient pressure at the temperature range of 0–1000 K. In the next step, we computed the phonon dispersion curves of six considered phases containing four stable configurations (P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4 and Fm–3 m-YB12) and two low-enthalpy metastable phases (Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6), as presented in Fig. 2. It should be pointed out that our phonon calculations confirm the dynamical stabilities of six concerned yttrium borides with the evidence of the absence of any imaginary frequencies over the entire Brillouin zones. Moreover, we have also conducted AIMD simulations to evaluate the thermal stability of six concerned yttrium borides at the temperature of 300 K with the time step of 2 fs and supercells of 144, 81, 112, 160, 56 and 52 atoms for Cmcm-YB, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, Pm–3 m-YB6, and Fm–3 m-YB12, respectively, as depicted in Fig. S3. The computed consequences substantiate that all six yttrium borides keep stable at the temperature of 300 K.

The convex hull diagram of the Y − B binary system under ambient pressure. The solid line expresses the ground-state convex hull.

Phonon dispersion curves of six considered Y–B compounds: (a) Cmcm–YB, (b) P6/mmm–YB2, (c) P121/c1–Y2B5, (d) P4/mbm–YB4, (e) Pm–3 m–YB6 and (f) Fm–3 m–YB12.

3.2 Detailed crystalline structural characteristics

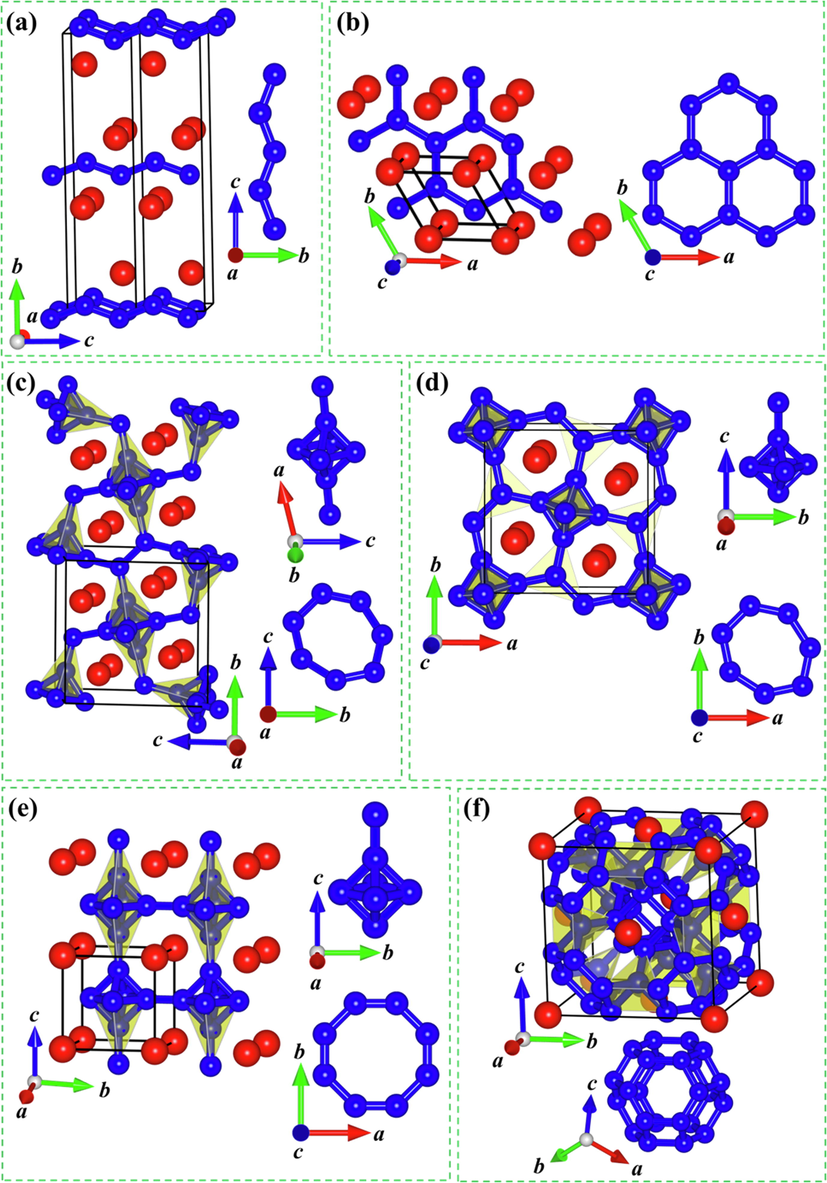

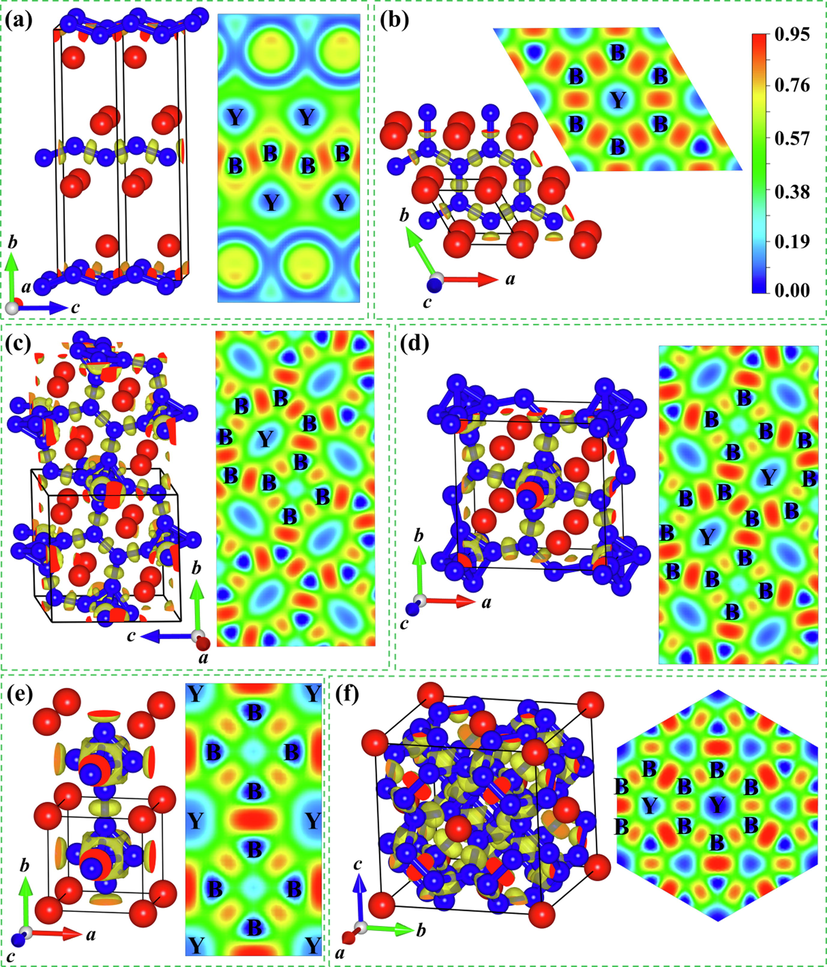

To look into the structural characters of six yttrium borides considered (Cmcm-YB, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, Pm–3 m-YB6, and Fm–3 m-YB12), we optimize their unit cell and draw the detailed structural diagrams in Fig. 3. Next, we probe into the detailed structural features according to the order of the increasing boron content. For the Cmcm-YB crystal, the unit cell contains four Y and four B atoms (see Fig. 3 (a)). In this crystalline structure, each Y atom is surrounded by six B atoms with two B atoms at a separation of 2.610 Å and four B atoms at a separation of 2.724 Å, forming a bottom regular triangular prism. The B atoms exhibit the zigzag arrangement along the c axis with the equal B–B bond length of 1.705 Å. In addition, the adjacent zigzag B chains are parallel to each other. These results indicate that the boron framework in the Cmcm-YB structure contains the zigzag B chains. Next, the hexagonal P6/mmm-YB2 phase in the AlB2-type structure (see Fig. 3(b)) contains the alternating B layers and Y layers within an intriguing B6–Y–B6 sandwiches stacking order along the c axis. It should be noted that each Y atom is located at the center of a regular hexagonal column with an equal Y–B bond distance of 2.710 Å and B atoms form parallel hexagonal planes with the equal adjacent B–B bond length of 1.903 Å. Thus, the boron network in the P6/mmm-YB2 crystal consists of the planar hexagonal B rings. The newly predicted P121/c1-Y2B5 structure (Fig. 3(c)) belongs to the monoclinic crystal system and is composed of eight Y atoms and twenty B atoms. Y atoms take the Wyckoff 4e positions, (0.232, 0.193, 0.627) and (0.242, 0.815, 1.253), while B atoms occupy-five nonequivalent sites in this unit cell, the Wyckoff 4e (0.503, 0.674, 0.540), 4e (0.501, 0.089, 1.410), 4e (0.503, 0.038, 1.174), 4e (0.074, 0.990, 0.925), and 4e (0.686, 0.002, 1.041) positions. In the P121/c1-Y2B5 structure, one Y atom is surrounded by twelve B atoms with the Y–B separations varying from 2.613 to 2.993 Å and the B–Y–B angles varying between 33°and 157°. Furthermore, this structure also contains distorted B6 octahedrons and seven-member B rings in one plane. Interestingly, the B6 octahedron consists of three different rectangles with the equal B–B bond length of the reciprocal opposite sides. Six B–B bond lengths are 1.786, 1.791, 1.794, 1.797, 1.808 and 1.816 Å, respectively. In the seven-member B ring, two equal B–B bond lengths are 1.722 Å, two equal B–B bond lengths are 1.723 Å, one B–B bond length is 1.780 Å. In the meantime, another two different B–B bond lengths, 1.786 and 1.794 Å, overlap with two equatorial B–B bond lengths of the B6 octahedrons. The consequences demonstrate that the boron framework for the P121/c1-Y2B5 structure is best described as distorted B6 octahedrons and seven-member B rings. In the tetragonal P4/mbm-YB4 polymorph (Fig. 3(d)), each Y atom is linked by 18 adjacent B atoms with four B atoms at a separation of 2.727 Å, four B atoms at a separation of 2.741 Å, four B atoms at a separation of 2.825 Å, four B atoms at a separation of 2.856 Å, and two B atoms at a separation of 3.069 Å. This crystal is also composed of slightly distorted B6 octahedrons and seven-member B rings in a plane. In this B6 octahedron, there exist two equal rectangular pyramids and each rectangular pyramid is composed of four identical isosceles triangles: eight lateral-edge B–B distances are 1.751 Å and four B–B distances in the basal surface are 1.811 Å. In the seven-member B ring, there exit four B–B distances of 1.718 Å, two B–B distances of 1.811 Å and one B–B distance of 1.746 Å. Simultaneously, the B–B distance of 1.811 Å is overlapping with the B–B distance in the basal surface of rectangular pyramid in B6 octahedron. In consequence, the boron construction of the P4/mbm-YB4 polycrystalline is constituted by slightly distorted B6 octahedrons and planar seven-member B rings. For the cubic Pm–3 m–YB6 configuration, as presented in Fig. 3(e), one Y atom possesses 24 adjacent B atoms with the equal Y–B distance of 3.010 Å. Moreover, this phase consists of two-dimensional eight-member B rings and regular B6 octahedrons with the equal B–B distance of 1.745 Å. In the planar eight-member B rings, there are four B–B bond lengths of 1.631 Å and four B–B bond lengths of 1.745 Å, declaring a slightly distorted planar eight-member B ring. Hence, the boron configuration for the Pm–3 m-YB6 structure can be characterized as slightly distorted planar eight-member B rings and regular B6 octahedrons. In the cubic Fm–3 m-YB12 polymorph, one Y atom is located at the center of the particular B24 cage with all the equal Y-B distance of 2.786 Å (Fig. 3 (f)). Furthermore, the special B24 cage is constructed from eight planar hexagons and six standard squares. In a two-dimensional hexagon, there are three B–B bond distances of 1.789 Å and three B–B bond distances of 1.722 Å. Based on the rounded analyses of the structural characters for six considered Y–B compounds, the B–B network of these six considered yttrium borides also undergoes a range of transformation with the increasing B concentration: zigzag B chains → planar hexagonal B rings → distorted B6 octahedrons and planar seven-member B rings → slightly distorted B6 octahedrons and planar seven-member B rings → regular B6 octahedrons and planar eight-member B rings → B24 cages. The results above demonstrate that the boron framework for six considered Y–B compounds transform from quasi one-dimensional chain to two-dimensional B ring to a combination of two-dimensional B ring and three-dimensional B6 octahedron to B24 cage as the B content increases, revealing the increasing dimension with the increasing B concentration in yttrium borides. Simultaneously, the Y–B distances in these six yttrium borides vary from 2.610 to 3.010 Å, which are larger than the sum (2.44 Å) of the covalent radii of Y (r = 1.62 Å) and B (r = 0.82 Å), revealing the inexistence of Y–B covalent bonding interaction. Moreover, the range of B–B bond lengths (1.631–1.903 Å) of the boron network is comparable to that of α-B (1.669–2.003 Å) (Li et al., 1992) and γ-B (1.661–1.903 Å) (Oganov et al., 2009); implying a B–B covalent network in six studied yttrium borides. Overall, the boron network in six considered Y–B compounds should have B–B covalent bond.

Crystal structures of six considered Y–B compounds: (a) Cmcm–YB, (b) P6/mmm–YB2, (c) P121/c1–Y2B5, (d) P4/mbm–YB4, (e) Pm–3 m–YB6 and (f) Fm–3 m–YB12. The red and blue spheres represent Y and B atoms, respectively.

3.3 Electronic properties and bonding features

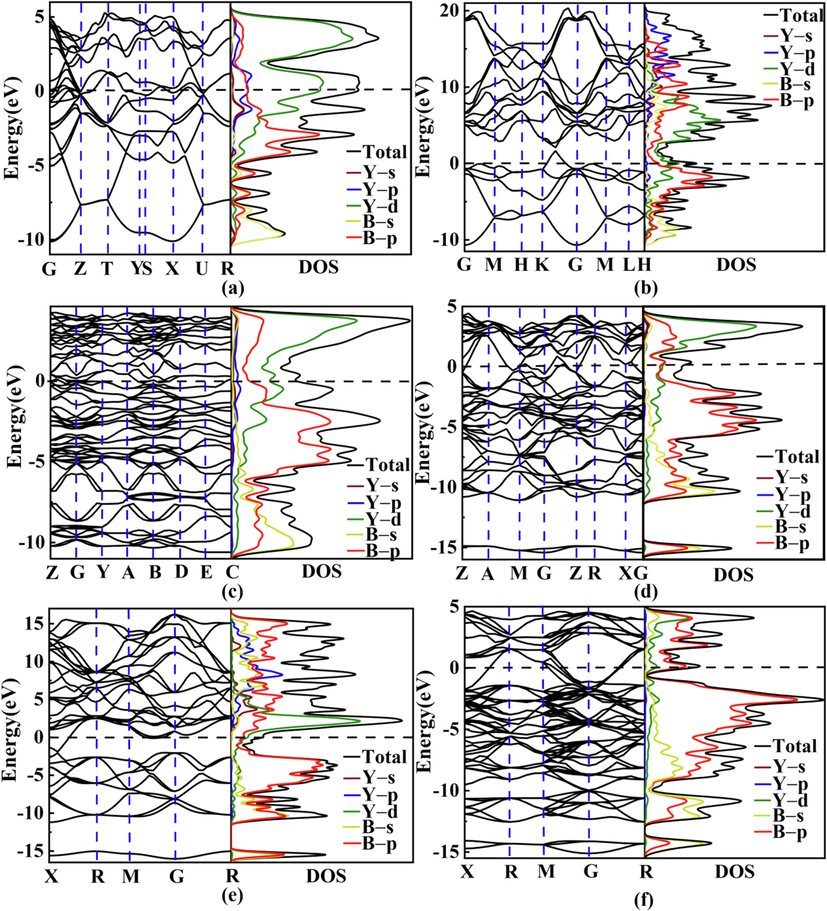

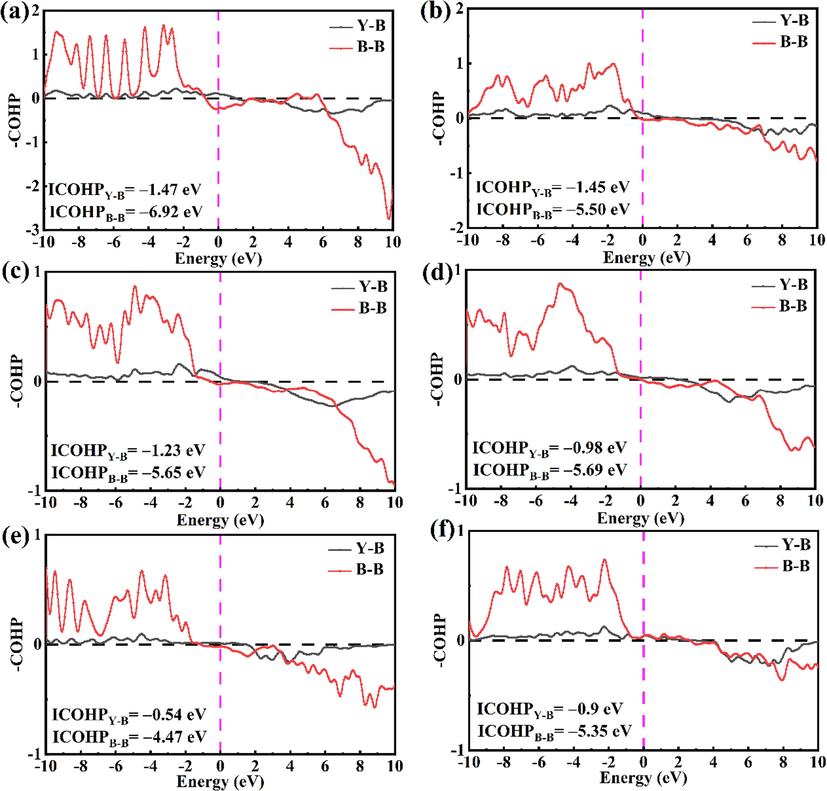

The intriguing structural features for six focused yttrium borides (Cmcm-YB, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, Pm–3 m-YB6, and Fm–3 m-YB12) further arouse our curiosity of exploring their electronic properties and bonding features. Following, we computed the band structures and density of states with the corresponding figures depicted in Fig. 4. Obviously, all the Y–B compounds present the metallic characters with the evidence of some energy bands crossing the Fermi level (EF). In addition, the total density of states (TDOS) near the Fermi level is largely contributed by the Y–4d and B–2p states. The unremarkable hybridization phenomenon between the Y–4d and B–2p states near the Fermi level reflects the relatively weak interaction between Y and B atoms. Meanwhile, the occupied electronic states in the valence region are dominated by B–2 s and B–2p states, while partial contributions from the Y atoms is trivial can be neglected. This indicates that the valence electrons of Y are mostly transferred to the B atoms and that the Y–B interaction in six considered Y–B compounds possesses the ionic character. To further explore the bonding nature of six studied yttrium borides, we computed their electron localization function (ELF) (Becke and Edgecombe, 1990; Savin et al., 1992), as plotted in Fig. 5. From Fig. 5, it is clearly seen that high electron localization exists in the region between B atoms, declaring the strong B–B covalent bonding within the boron framework in six considered yttrium borides. In comparison, ionic bonding is formed between Y and B atoms, which is in consistent with the aforementioned DOS analysis and corroborated by the further Bader partial charge analysis (see Table 1) (Bader, 1994), which stems from large amounts of charge transferred from Y to the B–B covalent network. To further clarify the relative bond strength between Y–B and B–B covalent framework for six concerned yttrium borides at ambient pressure, we have calculated the crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) and integral crystal orbital Hamilton population (ICOHP) as executed in the LOBSTER package (Dronskowski and Bloechl, 1993; Maintz et al., 2016); as displayed in Fig. 6. The predicted ICOHPs of B–B pair is much larger than that of Y–B pair, demonstrating that the B–B interaction is much stronger than that of Y–B. In short, we can speculate that the chemical bonding in six concerned yttrium borides comprises of positively charged metal Y cation and negatively charged B–B covalent framework. This bonding configuration can also be found in other metal borides, such as MgB2 (Tateishi et al., 2019), YB6 (Wang et al., 2018) and YB12 (Czopnik et al., 2005).

Band structures and density of states for six considered Y–B compounds: (a) Cmcm–YB, (b) P6/mmm–YB2, (c) P121/c1–Y2B5, (d) P4/mbm–YB4, (e) Pm–3 m–YB6 and (f) Fm–3 m–YB12.

Three-dimensional electron localization functions (ELFs) with an isosurface 0.77 and two-dimensional ELFs on the corresponding planes for six considered Y–B compounds. (a) Cmcm–YB (1 0 0), (b) P6/mmm–YB2 (0 0 1), (c) P121/c1–Y2B5 (1 0 0), (d) P4/mbm–YB4 (0 0 1), (e) Pm–3 m–YB6 (0 0 1) and (f) Fm–3 m–YB12 (1 1 1).

Composition

Space group

Atom

Change value (e)

δ (e)

YB

Cmcm

Y

9.89

1.11

B

4.11

–1.11

YB2

P6/mmm

Y

9.45

1.55

B

3.78

–0.78

Y2B5

P121/c1

Y

9.46

1.54

B

3.62

–0.62

YB4

P4/mbm

Y

9.29

1.71

B

3.43

–0.43

YB6

Pm-3 m

Y

9.13

1.87

B

3.31

–0.31

YB12

Fm-3 m

Y

9.22

1.78

B

3.15

–0.15

The crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) curves for (a) Cmcm–YB, (b) P6/mmm–YB2, (c) P121/c1–Y2B5, (d) P4/mbm–YB4, (e) Pm–3 m–YB6 and (f) Fm–3 m–YB12. The dotted vertical line at 0 eV denotes Fermi energy level.

3.4 Mechanical properties and Vickers hardness

Based on the robust thermal and dynamical stabilities under atmospheric pressure, as well as particular structural characters and strong covalent B–B frames, it is necessary to gain insight into the mechanical properties of six considered yttrium borides (Cmcm-YB, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, Pm–3 m-YB6, and Fm–3 m-YB12) which are important parameters for assessment as promising near-superhard or hard materials for engineering applications. Thus, we computed their elastic constants by employing the strain–stress method (Lu et al., 2010), as displayed in Table 2. Furthermore, the elastic constants can also be used to verify the mechanical stabilities of the materials. It is found from Table 2 that all the six considered yttrium borides meet their corresponding mechanical stability standard (Wu et al., 2007), confirming their mechanical stabilities. Based on the calculated elastic constants, the bulk modulus (B), shear modulus (G), Young's modulus (E), B/G, Poisson's ratio (ν) and Debye temperature (Θ) for six considered Y–B compounds were further estimated within the Voigt–Reuss–Hill method (Connétable and Thomas, 2009), as presented in Table 2. Beyond the present computed consequences, Table 2 also lists the previous theoretical results of P4/mbm–YB4 (Fu et al., 2014) and Pm–3 m–YB6 (Romero et al., 2019) for comparison. It can clearly be found that the calculated results in present work are consistent with the reported theoretical consequences (Fu et al., 2014; Romero et al., 2019); confirming the reliability of the present calculations. The predicted values of C11; C22, and C33 for six considered crystals are considerable, illustrating that they possess very strong incompressibility along a, b, and c axis, respectively. C44 is another significant parameter which is indirectly related to the indentation hardness of a material. As presented in Table 2, these four compounds studied (P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, and Fm–3 m-YB12) exhibit relatively high C44 values (>100 GPa), uncovering a strong strength of resisting the shear deformation. On the contrary, the remainder two compounds considered, Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6, have relatively low C44 values (<100 GPa), reflecting the weak shear strength.

Cmcm- YB

P6/mmm-YB2

P121/c1-Y2B5

P4/mbm-YB4

P4/mbm-YB4

Pm-3 m -YB6

Pm-3 m -YB6

Fm-3 m -YB12

C11

158

376

319

436

454a

447

455b

411

C12

59

57

37

78

80a

36

38b

128

C13

10

91

38

46

33a

C15

–34

C22

101

327

C23

29

66

C25

12

C33

277

339

305

431

442a

C35

9

C44

35

163

122

107

108a

31

21b

243

C46

9

C55

48

92

C66

54

70

128

132a

B

78

173

136

182

182a

173

176b

222

G

51

151

106

139

144a

74

64b

195

E

127

350

253

333

342a

194

171b

453

B/G

1.52

1.15

1.28

1.31

2.35

1.14

ν

0.23

0.16

0.19

0.19

0.18a

0.31

0.34b

0.16

Θ

400

743

660

818

874a

648

1166

Hv

9.31

27.49

18.83

22.29

7.34

5.49b

33.16

As is generally known, the bulk modulus B of a material is an index of the ability to resist uniform compression. The higher bulk modulus B of a material corresponds to the stronger ability in resisting uniform compression. From Table 2, the computed bulk modulus varies from 78 to 222 GPa. Among these six compounds studied, Fm–3 m–YB12 has the highest bulk modulus of 222 GPa, which is slightly less than that of common hard materials such as α-Ti3B4 (234 GPa) (Zhao et al., 2018) and β-Ti3B4 (235 GPa) (Zhao et al., 2018); Cmcm-HfB4 (239 GPa) (Chang et al., 2018); Cmcm-ZrB4 (234 GPa) (Chang et al., 2018); Fe3C (226.8 GPa) (Jang et al., 2009) and TiC (242 GPa) (Gilman and Roberts, 1961). To our knowledge, compared with bulk modulus, the shear modulus and Young modulus of a material exhibit stronger correlation with the hardness (Fulcher et al., 2012). As presented in Table 2, the Fm–3 m-YB12 phase possesses the largest shear modulus (195 GPa) and the highest Young modulus (453 GPa), revealing that this polycrystalline is expected to be the hardest compound among all the yttrium borides. In addition, another important parameter, B/G, is normally used to evaluate the ductility of a material. The high B/G ratio of a material (>1.75) can be classified into a ductile material while the low B/G ratio of a material (<1.75) corresponds to a brittle material (Pugh, 1954). In the view of classification rule, the Pm–3 m-YB6 compound possesses a B/G ratio of 2.35, demonstrating the ductile feature, while the other five crystals have B/G ratio < 1.75, suggesting brittle behaviors. The Poisson’s ratio ν is a critical target to estimate the degree of the directionality for the covalent bonds. As displayed in Table 2, the fact that the Poisson’s ratio ν for six focused yttrium borides (except for YB and YB6) are relatively low (<0.20) confirms their strong covalent bonding. Mechanical properties (in particular, hardness of a solid) are connected with thermodynamic parameters, including Debye temperature, specific heat, thermal expansion, and melting point (Abrahams and Hsu, 1975). In this concept, the Debye temperature (Θ) is one of the fundamental parameters for the characterization of materials and the hardness of a solid. Therefore, the Debye temperature (Θ) could be estimated on the account of the elastic constants at low temperature (Ravindran et al., 1998; Anderson, 1963). In Table 2, the derived Debye temperature (Θ) in YB12 can reach 1166 K, which is higher than those of ReB2 (755.5 K) (Aydin and Simsek, 2009), FeB4 (1089 K) (Zhang et al., 2013), TcB4 (1050 K) (Zhao and Xu, 2012), ReB4 (824 K) (Zhao and Xu, 2012). The Debye temperature value of YB12 is situated between that of superhard material ReB2 (755.5 K) and diamond (2230 K), indicating that YB12 should be harder than these superhard materials mentioned above (except for diamond).

In the view of the large shear modulus G, Young modulus E and Debye temperature Θ coupled with the small values for the B/G ratio and Poisson's ratio ν as tabulated in Table 2, the Fm–3 m–YB12 crystal may be expected to have high hardness among the Y-B compounds. We now further explore the Vickers hardness for six considered yttrium borides (Cmcm-YB, P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, Pm–3 m-YB6, and Fm–3 m-YB12) with the microscopic hardness model proposed by Tian et al (Tian et al., 2012). The Vickers hardness of complex crystals can be estimated by the following formula:

Herein, K = G/B, B and G represent the bulk modulus and shear modulus of the crystal. The calculated consequences for six concerning yttrium borides are summarized in Table 2. The fact that the present hardness values of 22.29 and 7.34 GPa for the P4/mbm-YB4 and Pm–3 m-YB6 crystalline structures are respectively consistent with the experimental value of YB4 (27.4 GPa) (Zaykoski et al., 2011) and the previous theoretical result for YB6 (5.49 GPa) (Romero et al., 2019) confirms the reliability of our calculations. The novel P121/c1-Y2B5 structure possesses a hardness value of 18.83 GPa, which approaches that of the famous hard material Al2O3 (20 GPa) (Andrievski, 2001), revealing the hard character. More importantly, the Vickers hardness value for YB12 can reach 33.16 GPa, which is higher than those of WB4 (31.8 GPa) (Gu et al., 2008), WC (30 GPa) (Haines et al., 2001); BP (33 GPa) (Andrievski, 2001); β-Si3N4 (30 GPa) (Andrievski, 2001), and TiC (32 GPa) (Guo et al., 2008), close to the lower limit of superhard materials (40 GPa). The analysis on the hardness of the YB12 compound suggests this crystal has the ultra-incompressible nature and can be regarded as a promising superhard material. Compared with the other four considered yttrium borides (P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, and Fm–3 m-YB12) with higher hardness values (>18 GPa), the Cmcm-YB and Pm–3 m-YB6 configurations possess the lower hardness values of 9.31 and 7.34 GPa. In general, the origin of differences in hardness is related not only to the strengths of B–B covalent bonds but also to the configuration of the boron framework. The Cmcm-YB phase with low hardness value can be ascribed to the zigzag B chain without the formation of the complex boron network, such as planar and three-dimensional covalent framework. Contrary to the Cmcm-YB phase, the Pm–3 m-YB6 crystal accompanied with the low hardness value should be attributed to the intrinsic ductile and soft character, which stems from the weak banana bond within the B6 octahedron (Zhou et al., 2015). Thus, the strong covalent B–B bond as well as the complex B–B covalent network are responsible for the high hardness, high shear modulus, high Young's modulus as well as low Poisson's ratio for four considered yttrium borides (P6/mmm-YB2, P121/c1-Y2B5, P4/mbm-YB4, and Fm–3 m-YB12).

4 Conclusions

To sum up, the exploration of the stable and metastable structures of boron-rich yttrium borides is a widely concerned subject in the fundamentally and practically functional materials because of their uniquely mechanical, superconductive and thermoelectric properties. In the present work, based on the CALYPSO prediction method coupled with the first-principles calculation, we conducted a systematical investigation on the stable and metastable configurations in the Y–B binary system, especially on the boron-rich side. In addition to four experimentally known phases, P6/mmm–YB2, P4/mbm–YB4, Pm–3 m–YB6 and Fm–3 m–YB12, we uncover a new stable Y2B5 compound with the monoclinic P121/c1 phase. In particular, the P121/c1–Y2B5 phase is a solely stable phase within an unprecedentedly fractional stoichiometry in the Y–B binary system. Structurally, the P121/c1-Y2B5 crystalline contains the distorted B6 octahedron and seven-member B ring. Moreover, the computed formation enthalpy, elastic constants, and phonon dispersion curves verify that the P121/c1–Y2B5 structure is energetically, mechanically, and dynamically stable, respectively. Further analysis on the bond length, density of states, electron localization function, Bader charge and crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) reveals that the bonding pattern in P121/c1–Y2B5 can be deemed as a combination of positively charged metal Y cation and negatively charged B–B covalent framework. Surprisingly, as the B content increases, the B–B bonding form in six concerned yttrium borides undergoes an increasing dimension, quasi one-dimensional chain → two-dimensional B ring → a combination of two-dimensional B ring and three-dimensional B6 octahedron → three-dimensional B24 cage. Based on a microscopic hardness model, the Vickers hardness value of P121/c1–Y2B5 is 18.83 GPa, indicating an incompressible and hard material. More interestingly, Fm-3 m-YB12 can be classified into an ultra-incompressible material with the significant hardness of 33.16 GPa. The high hardness for both phases can be attributed to the strong covalent B–B bond as well as the complex B–B covalent network. We anticipate that our work can motivate future experimental and theoretical investigations on the newly predicted boron-rich yttrium borides.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11804031, 11904297, 11904032 and 11747139), the Scientific Research Project of Education Department of Hubei Province (No. Q20191301), Talent and High Level Thesis Development Fund of Department of Physics and Optoelectronic Engineering of Yangtze University (C. Z. Z.), and Yangtze University Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (No. 2019364).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- A simplified method for calculating the Debye temperature from elastic constants. J Phys. Chem. Solids. 1963;24(7):909-917.

- [Google Scholar]

- Superhard materials based on nanostructured high-melting point compounds: achievements and perspectives. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater.. 2001;19(4–6):447-452.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles calculations of MnB2, TcB2, and ReB2 within the ReB2-type structure. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80(13):134107

- [Google Scholar]

- R.F. Bader, Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory (1994).

- A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys.. 1990;92:5397-5403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, elastic, mechanical and thermodynamic properties of HfB4 under high pressure. R. Soc. Open Sci.. 2018;5(7):180701

- [Google Scholar]

- Phase stability and superconductivity of lead hydrides at high pressure. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;103:035131

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of ultra-incompressible superhard rhenium diboride at ambient pressure. Science. 2007;316:436-439.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles study of the structural, electronic, vibrational, and elastic properties of orthorhombic NiSi. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;79:094101

- [Google Scholar]

- Osmium diboride, an ultra-incompressible, hard material. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2005;127:7264-7265.

- [Google Scholar]

- Low-temperature thermal properties of yttrium and lutetium dodecaborides. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2005;17:5971-5985.

- [Google Scholar]

- The crystal structure of a simple rhombohedral form of boron. Acta Crystallogr.. 1959;12:503-506.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structures, phase stabilities, electronic properties, and hardness of yttrium borides: new insight from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.. 2021;12:5423-5429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystal orbital Hamilton populations (COHP): energy-resolved visualization of chemical bonding in solids based on density-functional calculations. J. Chem. Phys.. 1993;97:8617-8624.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergent reduction of electronic state dimensionality in dense ordered Li-Be alloys. Nature. 2008;451:445-448.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elastic and dynamical properties of YB4: first-principles study. Chin. Phys. Lett.. 2014;31:116201

- [Google Scholar]

- Hardness analysis of cubic metal mononitrides from first principles. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:184106

- [Google Scholar]

- G. Ghosh, A.van de Walle, M. Asta, First-principles calculations of the structural and thermodynamic properties of bcc, fcc and hcp solid solutions in the Al−TM (TM = Ti, Zr and Hf) systems: a comparison of cluster expansion and supercell methods, Acta Mater. 56 (2008) 3202−3221.

- Discovery of a superhard iron tetraboride superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 2013;111:157002

- [Google Scholar]

- Peierls distortion, magnetism, and high hardness of manganese tetraboride. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:064108

- [Google Scholar]

- Q. Gu, Günter Krauss, W. Steurer, Transition metal borides: superhard versus ultra-incompressible, Adv. Mater. 20 (2008) 3620–3626.

- Crystal structures and formation mechanisms of boron-rich tungsten borides. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;104:014110

- [Google Scholar]

- Hardness of covalent compounds: roles of metallic component and valence electrons. J. Appl. Phys.. 2008;104:023503

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure refinement of YB62 and YB56 of the YB66-type structure. J. Solid State Chem.. 1997;133:16-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The elastic behavior of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. London, Sect. A. 1952;65:349.

- [Google Scholar]

- YB48 the metal rich boundary of YB66; crystal growth and thermoelectric properties. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2015;87:221-227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the electronic properties of YB4 and YB6 using 11B NMR and first-principles calculations. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2004;383:232-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- Substitutional solution of silicon in cementite: a first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci.. 2009;44:1319-1326.

- [Google Scholar]

- Y.Y. Jin, J.Q. Zhang, S. Ling, Y.Q. Wang, S. Li, F.G. Kuang, Z.Y. Wu, C.Z. Zhang, Pressure-induced novel structure with graphene-like boron-layer in titanium monoboride, Chin. Phys. B 10.1088/1674-1056/ac9222.

- A simple, general synthetic route toward nanoscale transition metal borides. Adv. Mater.. 2018;30:1704181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169-11186.

- [Google Scholar]

- From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758-1775.

- [Google Scholar]

- Superhard properties of rhodium and iridium boride films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2010;2:581-587.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advancements in the search for superhard ultra-incompressible metal borides. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2009;19:3519-3533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electronic structures, total energies, and optical properties of α-rhombohedral B12 and α-tetragonal B50 crystals. Phys. Rev. B. 1992;45:5895-5905.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computational analysis of stable hard structures in the Ti–B system. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:15607-15617.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abnormal physical behaviors of hafnium diboride under high pressure. Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2019;115:231903

- [Google Scholar]

- Superconductivity mediated by a soft phonon mode: specific heat, resistivity, thermal expansion, and magnetization of YB6. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:024512

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical investigation on the high-pressure structural transition and thermodynamic properties of cadmium oxide. Europhys. Lett.. 2010;91:16002.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elucidating stress-strain relations of ZrB12 from first-principles studies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.. 2020;11:9165-9170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrastrong boron frameworks in ZrB12: a highway for electron conducting. Adv. Mater.. 2017;29:1604003.

- [Google Scholar]

- LOBSTER: A tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem.. 2016;37:1030-1035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nosé-Hoover chains: The canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys.. 1992;97:2635-2643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tungsten tetraboride, an inexpensive superhard material. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(27):10958-10962.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of transition metal doping and carbon doping on thermoelectric properties of YB66 single crystals. J. Solid State Chem.. 2006;179:2889-2894.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure, bonding and possible superhardness of CrB4. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys.. 2012;85:144116

- [Google Scholar]

- Digital HREM imaging of yttrium atoms in YB56 with YB66 structure. J. Solid State Chem.. 1998;135:182-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of B concentration on the structural stability and mechanical properties of Nb−B compounds. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:23175-23183.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles determination of the soft mode in cubic ZrO2. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 1997;78:4063-4066.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 1996;77:3865-3868.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relations between the elastic moduli and the plastic properties of polycrystalline pure metals. Philos. Mag.. 1954;45:823-843.

- [Google Scholar]

- Density functional theory for calculation of elastic properties of orthorhombic crystals: Application to TiSi2. J. Appl. Phys.. 1998;84:4891-4904.

- [Google Scholar]

- The crystal structure of YB66. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem.. 1969;25:237-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles calculations of the structural, elastic, vibrational and electronic properties of YB6 compound under pressure. Eur. Phys. J. B. 2019;92:159.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermoelectric and magnetic properties of spark plasma sintered REB66 (RE=Y, Sm, Ho, Tm, Yb) J. Eur. Ceram. Soc.. 2020;40:3585-3591.

- [Google Scholar]

- A. Savin, O. Jepsen, J. Flad, O.K. Andersen, H. Preuss, H.G.v. Schnering, Electron localization in solid-state structures of the elements: the diamond structure, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 31 (1992) 187–188.

- Band structure of superconducting dodecaborides YB12 and ZrB12. Phys. Solid State. 2003;45(8):1429-1434.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth of single crystals of YB2 by a flux method. J. Cryst. Growth. 2001;223:111-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- High temperature allotropy and thermal expansion of the rare earth metals. J. Less-Common Met.. 1961;3:110-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second group of high-pressure high-temperature lanthanide polyhydride superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;102:144524

- [Google Scholar]

- Semimetallicity of free-standing hydrogenated monolayer boron from MgB2. Phys. Rev. Mater.. 2019;3:024004

- [Google Scholar]

- Microscopic theory of hardness and design of novel superhard crystals. Int. J. Refract Met. H.. 2012;33:93-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B. 2008;78(13):134106

- [Google Scholar]

- Pearson’s Crystal Data Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds. ASM International: Materials Park, OH; 2007.

- Crystal structure prediction via particle-swarm optimization. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:094116

- [Google Scholar]

- CALYPSO: a method for crystal structure prediction. Comput. Phys. Commun.. 2012;183:2063-2070.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-pressure evolution of unexpected chemical bonding and promising superconducting properties of YB6. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:27820-27828.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, mechanical and electronic properties and hardness of ionic vanadium dihydrides under pressure from first-principles computations. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2020;10:8868.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermoelastic properties of ScB2, TiB2, YB4 and HoB4: Experimental and theoretical studies. Acta Mater.. 2011;59:4886-4894.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incompressibility and hardness of solid solution transition metal diborides: Os1−xRuxB2. Chem. Mater.. 2009;21(9):1915-1921.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structures and elastic properties of superhard IrN2 and IrN3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:054115

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles study of the lattice dynamics, thermodynamic properties and electron-phonon coupling of YB6. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:214103

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of YB4 ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.. 2011;94(11):4059-4065.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Qin, J. Ning, X. Sun, X. Li, M. Ma, R, Liu, First principle study of elastic and thermodynamic properties of FeB4 under high pressure, J. Appl. Phys. 114 (2013) 183517.

- The crystal structures, phase stabilities, electronic structures and bonding features of iridium borides from first-principles calculations. RSC Adv.. 2022;12:11722-11731.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stability and strength of transition-metal tetraborides and triborides. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 2012;108:255502

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of novel high-pressure structures of magnesium niobium dihydride. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:26169-26176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible pitfalls in theoretical determination of ground-state crystal structures: the case of platinum nitride. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;79:092102

- [Google Scholar]

- Unexpected stable phases of tungsten borides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2018;20:24665-24670.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles calculations of MnB4, TcB4, and ReB4 with the MnB4-type structure. Comp. Mater. Sci.. 2012;65:372-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- YB6: a ‘Ductile’ and soft ceramic with strong heterogeneous chemical bonding for ultrahigh-temperature applications. Mater. Res. Lett.. 2015;3:210-215.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104546.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1