Translate this page into:

CuI nanoparticles-immobilized on a hybrid material composed of IRMOF-3 and a sulfonamide-based porous organic polymer as an efficient nanocatalyst for one-pot synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans

⁎Corresponding author. ghorbani@basu.ac.ir (Ramin Ghorbani-Vaghei)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

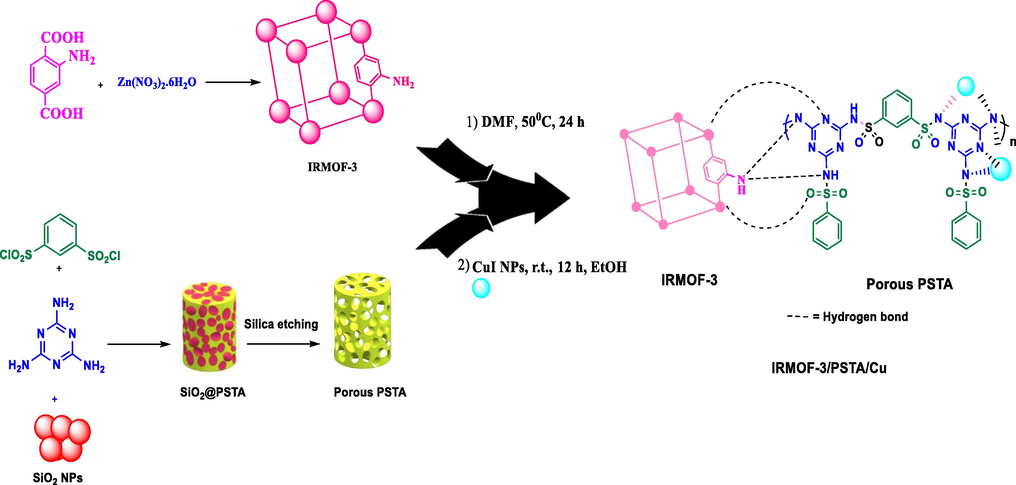

This study was conducted to synthesize and characterize a new polymer/metal–organic framework (MOF) stabilizer via the reaction between a sulfonamide-triazine-based porous organic polymer (poly(sulfonamide-triazine)) (PSTA) and an amino-functionalized zinc metal–organic framework (IRMOF-3). Next, the prepared nanocomposites (IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu) were modified using copper iodide nanoparticles (CuI NPs). The composites were characterized by FT-IR, XRD, EDX, N2 adsorption–desorption, TGA, SEM, TEM, and XPS analysis. Finally, the application of the prepared nanocomposites was investigated through the one-pot synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans. To this end, alkyne, salicylaldehydes, and amines were subjected to a three-component domino reaction. All products were obtained in high turnover frequency (TOF) up to 142.42, suggesting this catalyst’s high selectivity and activity in the mentioned domino reactions. The synthesized nanocatalyst is reusable up to seven times with no considerable catalytic efficiency loss. Overall, the high yields of products, nanocatalyst’s facile recovery, short reaction time, and wide substrate scopes make this procedure eco-friendly, practical, and economically justified.

Keywords

IRMOF-3

Polymer/metal–organic framework

Nano porousmaterials

Benzo[b]furan

Copper iodide

Three-component coupling

1 Introduction

Multicomponent domino reactions are efficient tools for synthesizing large and complex molecules (Sun et al., 2021; Erfaninia et al., 2018; Kazemi and Mohammadi, 2020). In these reactions, three or more components are mixed through a single chemical step to synthesize products with considerable portions of each component (Mohammadi and Ghorbani-Choghamarani, 2022; Shabanloo et al., 2020; Ghorbani-Vaghei et al., 2018). This reaction occurs through a powerful, economically justified, and facile procedure (Jamshidi et al., 2018; Tayebee et al., 2019; Koosha et al., 2023; Ghobakhloo et al., 2022). Multicomponent domino reactions have been the subject of intense research in the synthetic organic chemistry community. Accordingly, they have been utilized to prepare various biological and pharmacological products (Wang et al., 2022; Alavinia et al., 2023; Bahiraei et al., 2021; Solgi et al., 2022).

Benzofurans are specific heterocyclic pharmacophores with diverse medicinal chemistry and several interesting pharmacological and therapeutic characteristics (Dwarakanath and Gaonkar, 2022). They are also used as the core moieties for preparing many well-known drugs with antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and many other pharmaceutical and bioorganic features. For instance, obovaten is an active antitumor agent, and XH-14 is the first reported potent nonnucleoside adenosine A1 agonist (Scheme 1) (Nair and Baire, 2021; Morgan et al., 2021). The main techniques to prepare benzo[b]furans include coupling the o-iodophenols and aryl acetylenes, intramolecular cyclization of substituted allyl–aryl ethers, dehydrative annulation of phenols containing appropriate ortho vinylic substituents, dehydrative cyclization of a-(phenoxy)-alkyl ketones, (Kazemi and Mohammadi, 2020; Kazemi and Mohammadi, 2020)-sigmatropic rearrangement of various arenes, reactions of 2-hydroxybenzaldehydes, amines, and alkynes using different catalysts, and Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction of 2-iodonitrophenol acetates (Morgan et al., 2021; Deng and Meng, 2020; Lavanya et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2022). In this respect, each technique has specific advantages and opens a new horizon in synthesizing 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans (Chiummiento et al., 2020). Nevertheless, such catalytic systems have shortcomings such as the long reaction time, tedious workup, difficult reusability and recovery of metal catalysts, and not being eco-friendly.![Representative examples of benzo[b]furans scaffolds found in some drugs.](/content/184/2023/16/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.104975-fig1.png)

Representative examples of benzo[b]furans scaffolds found in some drugs.

Recently, several studies have been conducted on nanocomposite materials because of the unique surface properties of these heterogeneous catalysts in different organic reactions (Mohammadi et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022). Therefore, researchers endeavor to refine these materials toward reaching sustainable development (Zolfigol et al., 2003; Rahimzadeh et al., 2022). Conventional porous polymers have found multiple industrial uses regarding their facile processability and low cost (Esen and Kumru, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Mohamed et al., 2022). Nonetheless, their performance is restrained in terms of reusability due to selectivity and permeability issues (Zhang et al., 2022; Daliran et al., 2022). In this respect, incorporating inorganic components into the polymer is among the efficient methods to deal with this limitation (Luo et al., 2021). Recently, carbon nanotube, zeolite, graphene, metal–organic frameworks (MOF), and covalent organic frameworks (COF) have been reported as the inorganic materials suitable for this purpose (Daliran et al., 2022; Ramish et al., 2022; Ghorbani-Choghamarani et al., 2021).

Metal-organic framework materials contain inorganic metal centers (or clusters) coordinated with organic linkers (Koolivand et al., 2022; Behera et al., 2022). These materials have tunable surface functionalities, large surface areas, pore channels with regular geometry, and controllable porosity and pore size (Xiao et al., 2022). Because of their inherent advantages, MOFs have been widely used in constructing biomedicine, chemical sensing, and heterogeneous catalysts (Rego et al., 2022; Peng et al., 2022). In this regard, MOF is a promising inorganic compound incorporated in a polymer matrix to synthesize a polymer/MOF nanocomposite (Tombesi and Pettinari, 2021; Guo et al., 2022). However, this system offers low compatibility between the polymer and MOF, leading to a defective structure and irregular morphology (McDonald et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2022). In this respect, the choice of polymer and MOF matrix pair is essential in polymer/MOF construction regarding its role in their performance and morphology.

Isoreticular metal–organic framework-3 (IR-MOF-3) is an important MOF with a cubic framework (Karami and Khodaei, 2022). The structure has free –NH2 functional groups non-attached to tetragonal ZnO4 as nodes. Such a feature allows for modifying IR-MOF-3 with various organic and organometallic compounds (Scheme 2) (Mozaffari et al., 2022). The hybridization of MOF with other functional substances is a fascinating research field to produce novel materials with better properties than the individual components (Zolfigol et al., 2003; Ghorbani-Choghamarani et al., 2021).

Schematic representation of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu.

Mesoporous polysulfonamides are among other highly interesting compounds for preparing heterogeneous catalysis (Alavinia and Ghorbani-Vaghei, 2020). Mesoporous polysulfonamides have good chemical stability, great surface area, and a low skeleton density (Alavinia and Ghorbani-Vaghei, 2020; Alavinia et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2021). In this regard, a careful selection of monomers and templates is essential in these materials’ electronic, chemical, and topological features (Rieger et al., 2018; Hwang et al., 2022; Imai et al., 1977). Also, the silica template technique has been used to prepare a novel porous sulfonamide-triazine-based polymer support (PSTA) (Scheme 2).

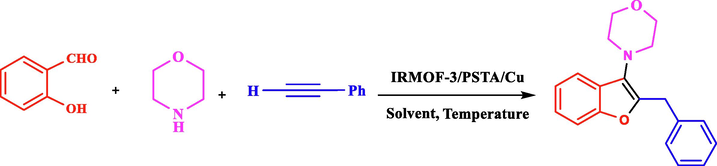

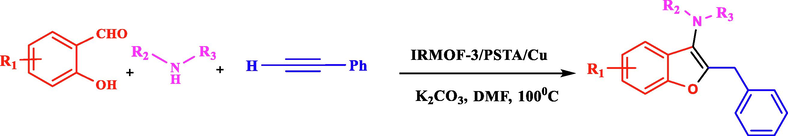

Regarding the mentioned points, the present article introduces a new nanocomposite material consisting of IRMOF-3 and PSTA, offering advantages of both materials. Combining these two agents can improve the binding sites, thermal stability, and loading level of metal of the produced support. CuI NPs were then successfully decorated on prepared support (IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu). Eventually, the nanocatalyst was incorporated successfully in a three-component reaction to prepare the new 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans through mild reaction conditions (Scheme 3).![Synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans using IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu.](/content/184/2023/16/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.104975-fig3.png)

Synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans using IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials and methods

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Merck in high purity. All the materials were of commercial reagent grade and were used without further purification. In addition, flash-column chromatography was performed by using Merck silica gel 60 with freshly distilled solvents. All melting points were uncorrected and determined in a capillary tube on a Boetius melting point microscope. Moreover, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker 400 MHZ spectrometer with CDCl3 as solvent using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were collected using a Rigaku model Ultima-IV diffractometer and Cu-Kα radiation (1.5405 Å) at 40 kV and 25 mA over a 2θ range of 20° to 90°. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) samples were created by pouring ethanolic solutions onto alumina stubs and coating them with gold using an automatic gold coater (Quorum, Q150T E). The energy-dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) used for the elemental analysis and mapping were obtained using an Oxford Instruments INCA attachment on a Lyra 3 SEM (dual beam) from TESCAN. TEM images were obtained using a JEM2100F transmission electron microscope from JEOL. The TEM samples were prepared by dropping them from an ethanolic suspension onto a copper grid and allowing them to dry at room temperature. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry was used to determine the amount of Ir nanoparticles in the catalyst (ICP-OES; PlasmaQuant PO 9000 – Analytik Jena). The catalyst samples were initially digested in a dilute mixture of HNO3 and HCl. Ir calibration curves were produced using standard solutions (ICP Element Standard solutions, Merck). An X-ray photoelectron spectroscope (XPS) was used to measure the surface composition and oxidation states. To this end, an X-ray monochromator with an Al-K micro-focusing microprobe (ESCALAB 250Xi XPS, Thermo Scientific, USA) was used. Base pressure was applied to calibrate the binding energy scale.

2.2 Synthesis of IRMOF-3

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (1.895 g) and 2-aminoterephthalic acid (0.370 g) were dissolved in DMF solvent by sonication (50 mL). After ensuring the container was sealed and impermeable, the solution was heated at 100 ℃ (in an oven) for 1 day. To remove DMF guest molecules from IRMOF-3, the prepared crystals were isolated, washed with DMF and chloroform three times, and soaked in chloroform for 1 day. Finally, they were dried at 50 ℃ under reduced pressure (Nabipour et al., 2021).

2.3 Synthesis of porous PSTA

SiO2/PSTA NPs were synthesized through in-situ polymerization of 1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triamine (0.7 mol) and benzene-1,3-sulfonyl chloride (1 mol) in the presence of acetonitrile (30 mL) and SiO2 NPs (0.1 g). The reaction mixture was stirred for 6 h under reflux conditions. Afterward, the nanocomposites were washed using ethanol and water. In the next step, it was filtered and vacuum dried at room temperature (RT). Furthermore, the silica template was removed by etching the SiO2 NPs with an aqueous HF solution. HF solution (10 mL, 10 wt%), deionized water (10 mL), and SiO2/PSTA NPs (0.5 g) were added to a 5 mL flask. Then, the mixture was stirred for 6 h at room temperature. Eventually, the produced porous polymer was washed using water and then dried at 50 ℃.

2.4 Synthesis of porous IRMOF-3/PSTA

A novel IRMOF-3/PSTA nanocomposite was synthesized by reacting IRMOF-3 with porous PSTA. To this end, 18 mg of IRMOF-3 was dispersed in N, N-dimethylformamide (5 mL), followed by adding PSTA (12 mg in 5 mL DMF) to the mixture dropwise. Afterward, the mixture was stirred and heated overnight at 50 ℃. Finally, the solid was dried at 110 ℃ for 24 h to remove residual solvent and yield the IRMOF-3/PSTA.

2.5 Synthesis of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite

About 0.1 g of the prepared IRMOF-3/PSTA support was added to an ethanol solution of CuI NPs (0.05 g in 20 mL), followed by stirring the mixture for 12 h. The IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposites were then isolated, washed with ethanol (2 × 25 mL) and water (2 × 25 mL), and dried at 50 ℃.

2.6 General procedure for the preparation of benzo[b]furan derivative using IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu

A mixture of phenylacetylene (0.17 mL, 1.5 mmol), IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (0.01 g, 0.88 mol%), K2CO3 (0.138 g, 1.0 mmol), morpholine (0.087 mL, 1.0 mmol), and salicylaldehyde (0.20 mL, 2.0 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) at 100 ℃ was stirred by a magnetic stirrer. The reaction progress was continuously monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). After completing the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and then centrifuged to separate the catalyst. Afterward, the obtained solid was recrystallized from ethyl acetate to give the pure product.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite

3.1.1 FT-IR studies

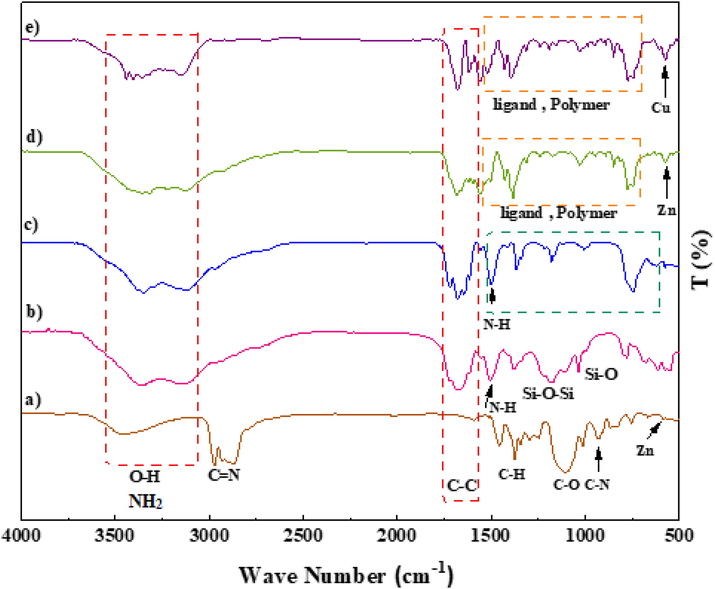

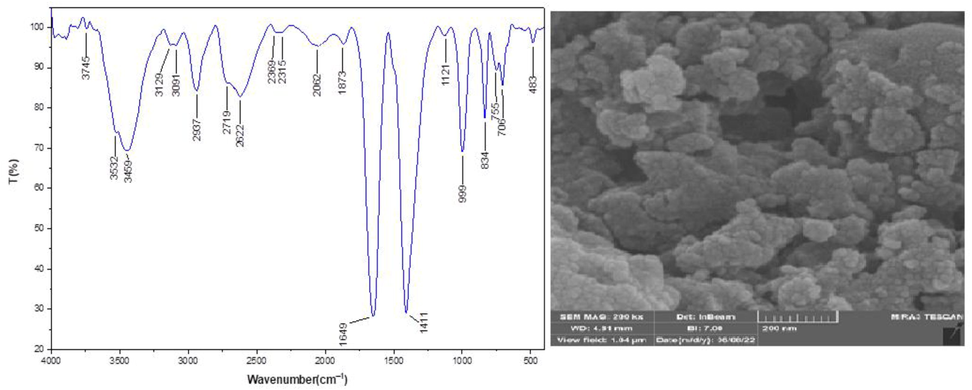

A prominent peak appeared at 3000–4000 cm -1 corresponds to the amino group of the stretching vibration. The sharp bands from 1682 to 1344 cm -1 signify C⚌C stretching vibrations of a benzene ring and symmetric and asymmetric modes of the dicarboxylate groups. Furthermore, the peaks at 1101 and 830 cm−1 correspond to aromatic C—H bending vibrations. The absorption peak at 681 cm−1 is due to the metal–oxygen bond of Zn—O (Fig. 1a). Regarding the SiO2/PSTA sample, the weak peak at 812 cm−1 and the sharp and broad absorption peaks at 1099 cm−1 are attributed to symmetric and asymmetric Si-O-Si bond stretches, respectively. Vibrational bands observed at 1160 and 1338 cm -1 represent the sulfone bridge presence in the catalyst. Absorption peaks at 1660, 1680, and 1645 cm−1 also relate to the melamine presence in the studied structure (Fig. 1b). Because of the template’s selective removal, SiO2 NPs peak was not observed in the porous PSTA (Fig. 1c). After the hybridization of IRMOF-3 with porous PSTA, the characteristic absorption bands (as previously described) were observed (Fig. 1d). Adding CuI NPs to the structure of IRMOF-3/PSTA significantly changed the FTIR spectra (1685 vs. 1665 cm -1). Moreover, the bands at 3344 cm−1 and 3248 cm−1 correspond to the NH2 stretching vibrations that shifted to a lower wavenumber than 3355 cm−1 and 3257 cm−1 due to the NH2 stretching vibrations on IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (Fig. 1e).

FT-IR spectra of IRMOF-3 (a), SiO2/PSTA (b), porous PSTA (c), IRMOF-3/PSTA (d), and IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (e).

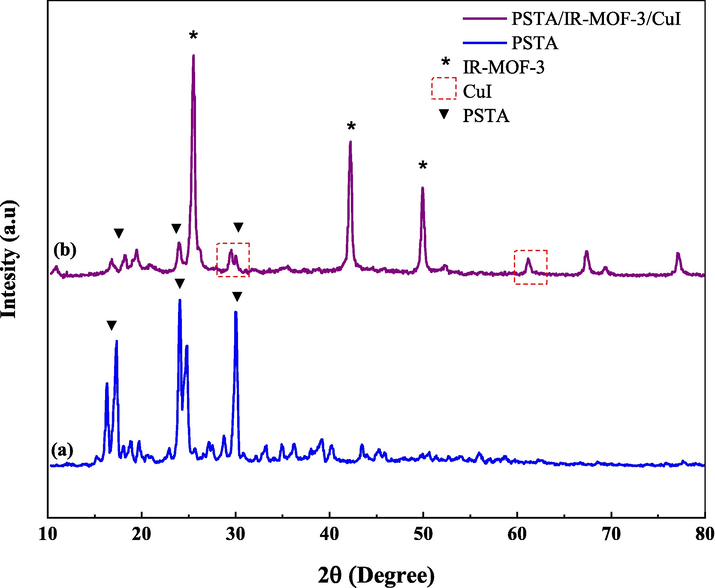

3.1.2 XRD analysis

XRD measurements were performed to evaluate the prepared porous IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu and PSTA in terms of their crystalline structure (Fig. 2). The XRD pattern of the prepared porous PSTA revealed a high degree of crystallization and characteristic peaks of sulfonamide and triazine at 2θ = 17.34°, 24.04°, and 29.99° (Fina et al., 2015). Furthermore, no SiO2 NP peaks were observed in the XRD spectra of porous PSTA (Fig. 2a). As can be seen from the XRD pattern of the final catalyst (Fig. 2b), the XRD pattern of the synthesized IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu catalyst has all characteristic peaks of IRMOF-3 (2θ = 25.54°, 42.24°, and 49.89°) (Luan et al., 2015), porous PSTA (2θ = 18.19°, 23.94°, 29.99°), and CuI NPs (2θ = 29.54°, 61.29°) (Alavinia et al., 2020). This result suggests the successful hybridization and presence of inorganic and organic phases in the nanocomposite matrix. As can be seen, the peak intensity of PSTA decreases at 2θ = 18.19°, 23.94°, and 29.99°. This alteration is due to the interactions between the PSTA and IRMOF-3. Also, the size of the IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite crystals was calculated to be 35.6 nm using the Scherer equation, indicating the IR-MOF-3′s preserved crystalline structure.

XRD pattern of porous PSTA (a) and IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (b).

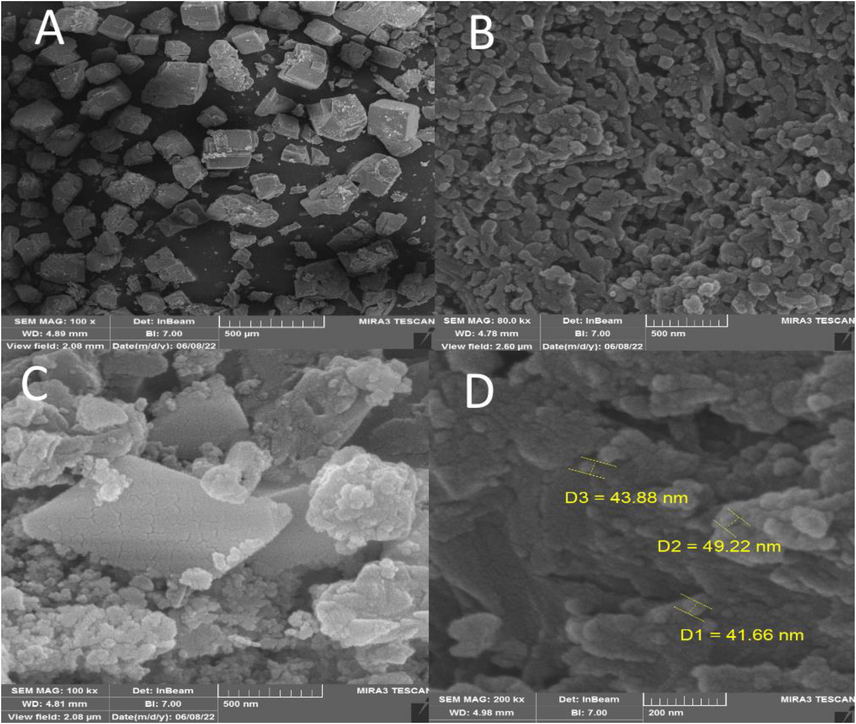

3.1.3 FESEM analysis

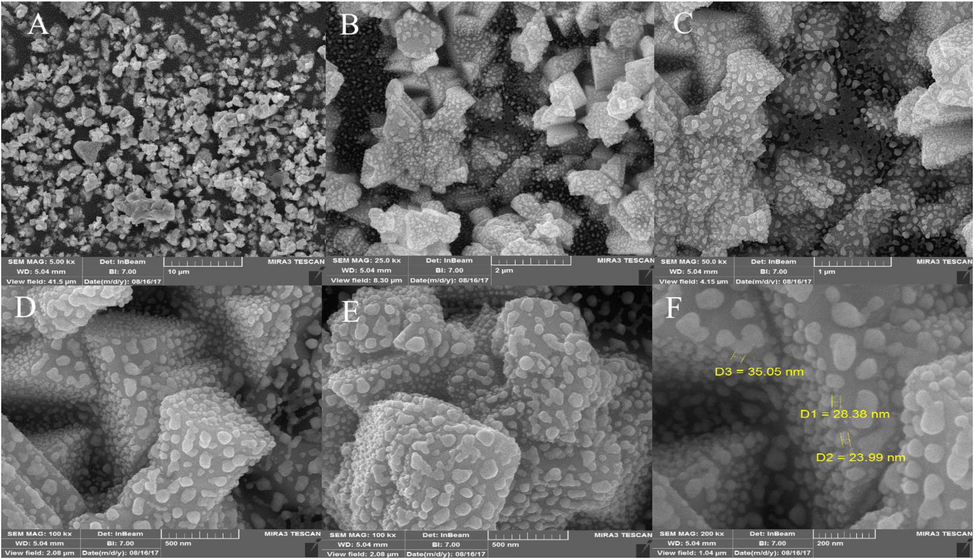

FESEM was performed to investigate the size and surface morphology of IRMOF-3, porous PSTA, IRMOF-3/PSTA, and IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (Fig. 3). A well-distributed, nearly cubic, and uniform nanostructure with a grain size of 30–50 nm was observed in the synthesized IRMOF-3 (Fig. 3a). In addition, FESEM images of PSTA (Fig. 3b) were captured for SiO2/PSTA nanocomposites using selective removal of the silica template. As can be seen, the prepared sample has a 3D porous, regular network with numerous spherical nanopores. The FESEM image of IRMOF-3/PSTA indicates the spherical structure of PSTA developed on IRMOF-3′s surface. Moreover, they exhibited a complex and porous nature (Fig. 3c). In Fig. 3d, spherical CuI particle distribution on IRMOF-3/PSTA is evident in the FESEM images of the prepared nanocatalysts.

SEM images of IRMOF-3 (a), porous PSTA (b), IRMOF-3/PSTA (c), and IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NCs (d).

The morphology and particle size of CuI nanoparticles were investigated using an SEM image of CuI nanoparticles presented in Fig. 4. These results show that spherical CuI nanoparticles were obtained with an average diameter of 10–30 nm (Fig. 4a-f).

FESEM images of CuI nanoparticles.

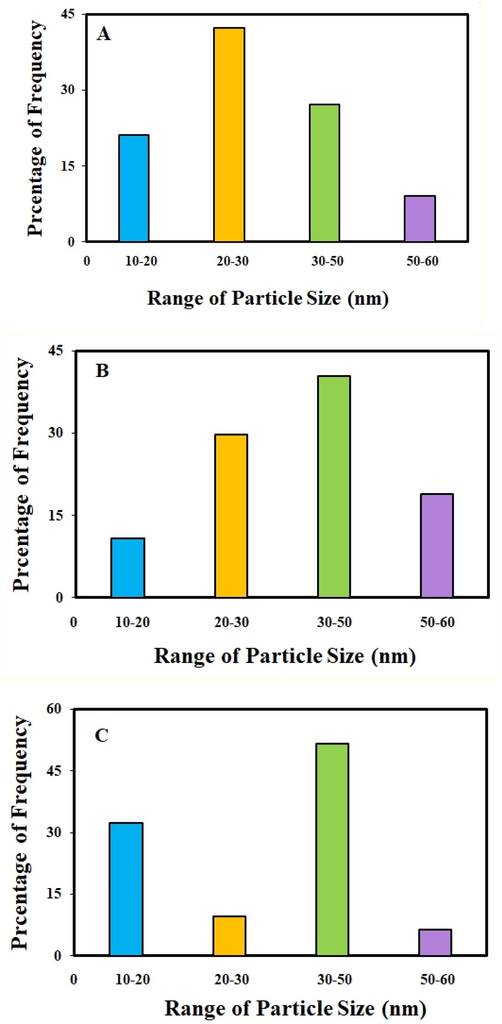

Moreover, the size distribution histogram of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NCs (Fig. 5a), CuI NPs (Fig. 5b), and IRMOF-3 (Fig. 5c) confirm that their average size diameter is less than 50 nm.

The particle size distributions of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NCs (a), CuI NPs (b), and IRMOF-3 (c).

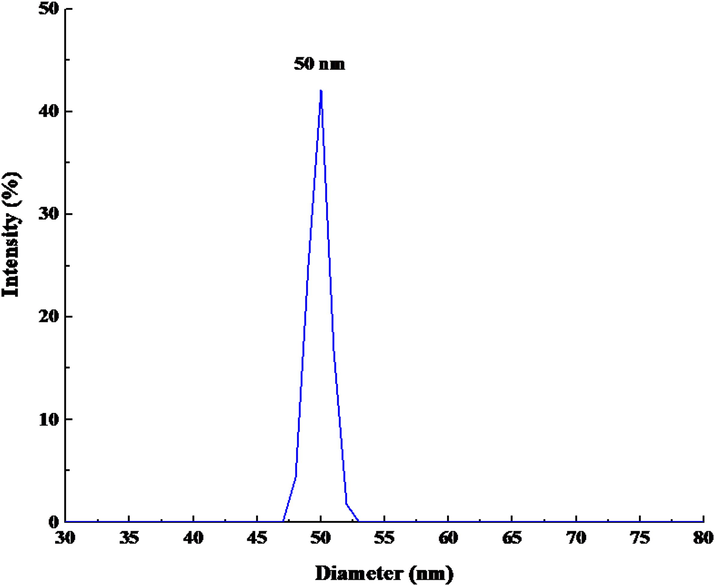

3.1.3.1 Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Based on the results of DLS (Fig. 6), the particle size in nanometers for IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NCs was equal to 50 nm. Generally, nanoparticle sizes obtained from DLS analyses are greater than other analyses such as SEM and XRD. This phenomenon is attributed to the effect of coating and stabilizer substances that stack on the surface of nanoparticles (Emami et al., 2023).

DLS result of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocatalyst.

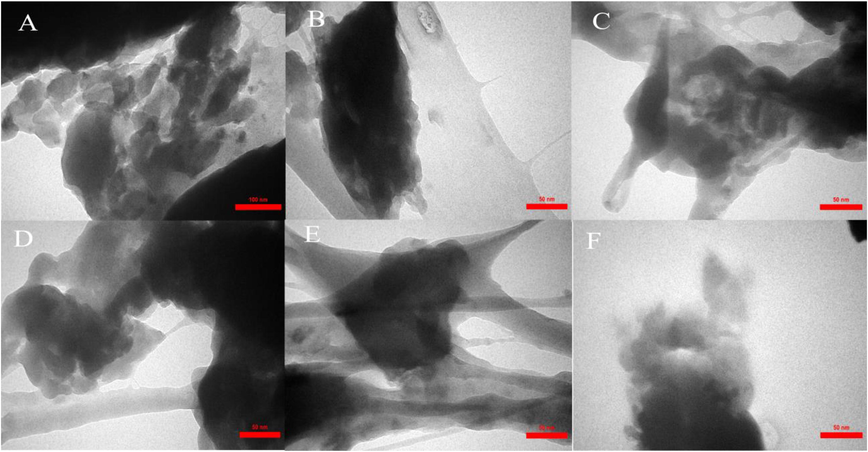

The size distribution of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was investigated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM images of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu show a nanocomposite structure (Fig. 7).

TEM image of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite.

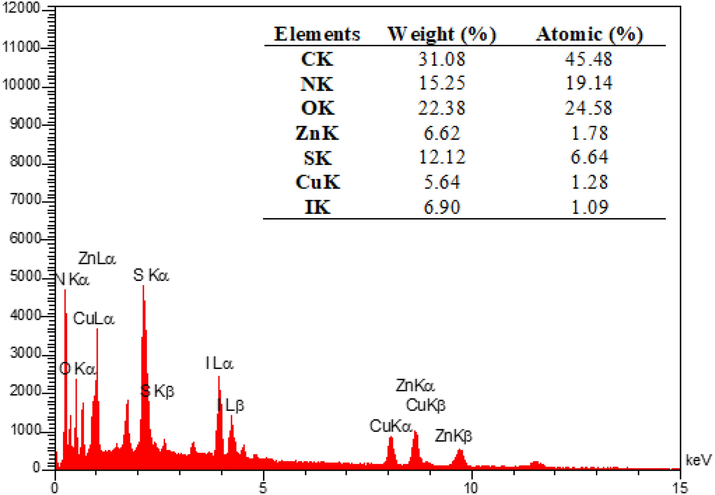

3.1.4 EDS and ICP-AES analysis

The EDX analysis was performed to determine the elemental composition of the IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NPs, which confirmed the presence of catalytic components (Fig. 8). Elemental mapping studies of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu NPs show a uniform distribution of carbon, copper, oxygen, iodide, nitrogen, sulfur, and zinc components in the fabricated structure (Fig. 9). In addition, the ICP-AES analysis of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu showed 0.88 mmol/g Cu.

EDX spectrum of IRMOF-3/PSTA@Cu nanocomposite.

Elemental mapping of the C, N, O, S, Cu, Zn, and I atoms achieved from SEM micrographs.

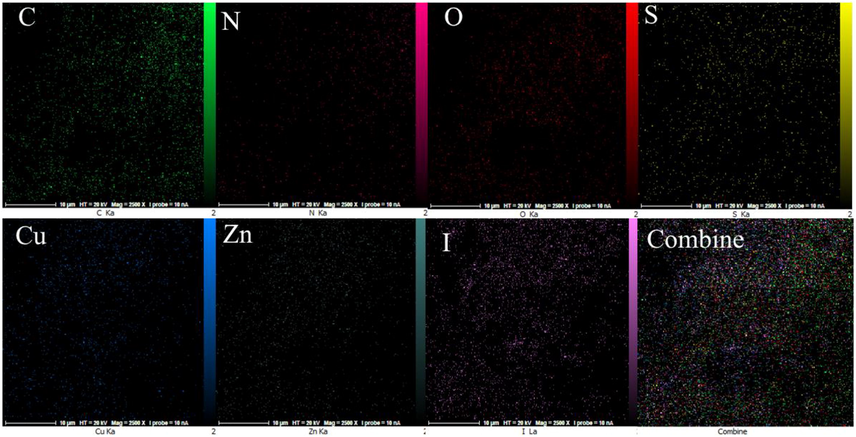

3.1.5 Thermogravimetric analysis

In this research, TGA was performed to investigate the stability of the prepared catalyst (Fig. 10). The TGA curve of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu shows three stages of degradation. Through steps 1, 2, and 3, this composite decomposes at 59.39, 382, and 546.87 ℃, respectively, typically losing 62.63% of its weight. The first step, starting at 25–236.4 ℃, is attributed to solvent removal and thermal condensation of melamine to produce NH3 and carbon nitride (CN) (Nabipour et al., 2021). Step 2, starting at 236.4-382 ℃, is due to the decomposition of the polymer backbone. Finally, step 3, i.e., from 382 to 546.87, is attributed to the MOF backbone (Fig. 10).

TGA curve of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu.

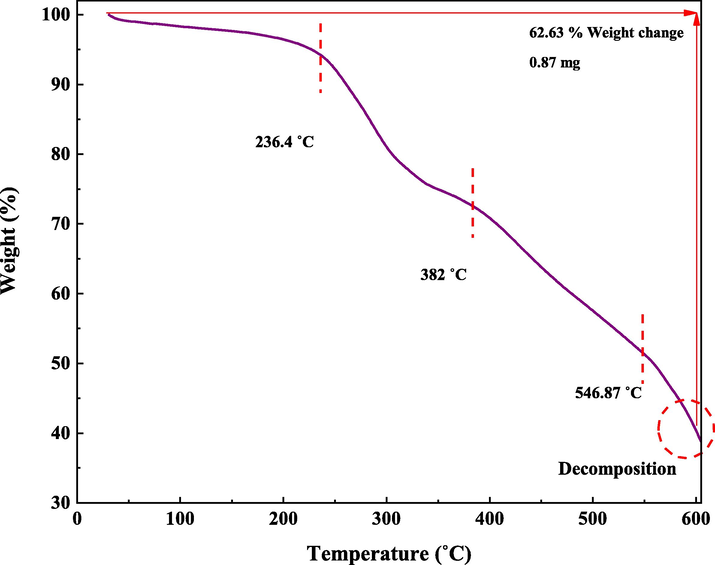

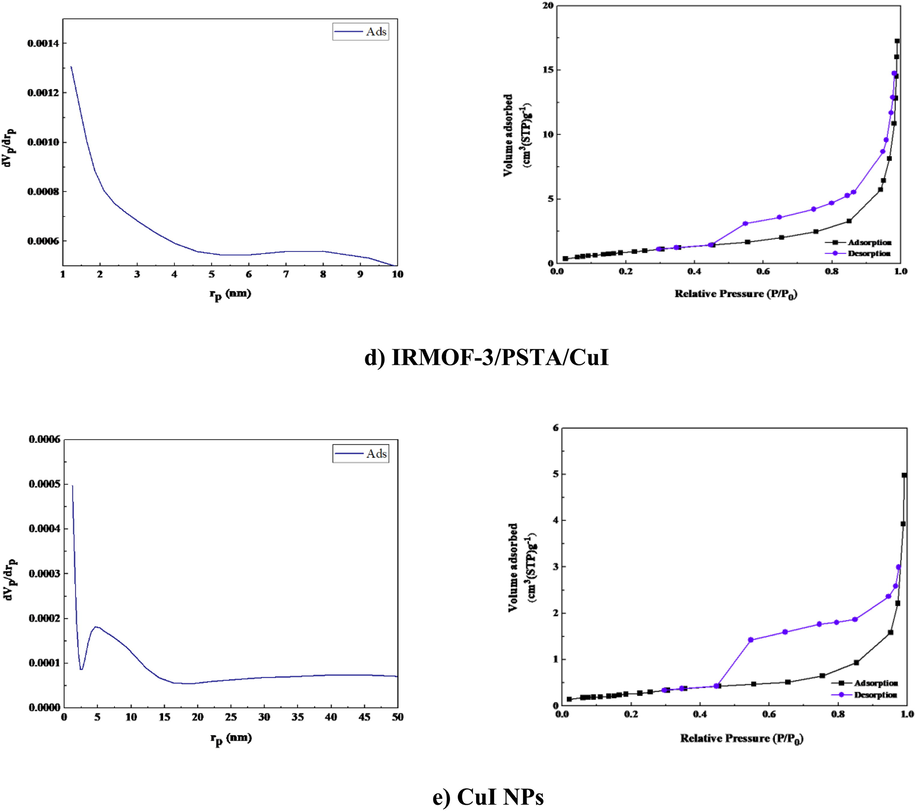

3.1.6 Porosity studies

BET analysis was carried out on the N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of IRMOF-3, PSTA, and IRMOF-3/PSTA nanostructures. A characteristic type IV H4 hysteresis loop was observed in the synthesized compound, indicating an ordered mesoporous structure (Fig. 11). The specific surface areas of IRMOF-3, porous PSTA, and IRMOF-3/PSTA are 34.96, 2.67, and 19.05 m2/g, respectively (Table 1). As expected, the observed decrease in the synthesized composites is mainly due to the modification of IRMOF-3 by porous PSTA. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI catalyst indicate no obvious change in the catalyst composition after copper nanoparticle immobilization (Fig. 11d). The changes associated with the textural properties of the IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI catalyst can be attributed to copper nanoparticles distributed inside the IRMOF-3/PSTA pores. The surface areas for CuI NPs were found to be 1.125 m2/g. Furthermore, a pore volume of 0.258 cm3/g and a pore diameter of 1.21 nm were achieved by BJH analysis (Fig. 11e).

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of IRMOF-3 (a), PSTA (b), IRMOF-3/PSTA (c), IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI (d), and CuI NPs.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of IRMOF-3 (a), PSTA (b), IRMOF-3/PSTA (c), IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI (d), and CuI NPs.

Parameter

IRMOF-3

PSTA

IRMOF-3/PSTA

IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI

CuI NPs

as (m2/g)

34.96

2.67

19.05

3.86

1.125

Vm (cm3(STP) g−1)

11.31

0.81

6.1

0.888

0.258

Vp (cm3g−1)

0.36

0.017

0.18

0.026

0.007

rp (nm)

71.9

1.64

53.04

1.21

1.21

ap (m2/g)

34.54

5.64

19.52

5.007

1.37

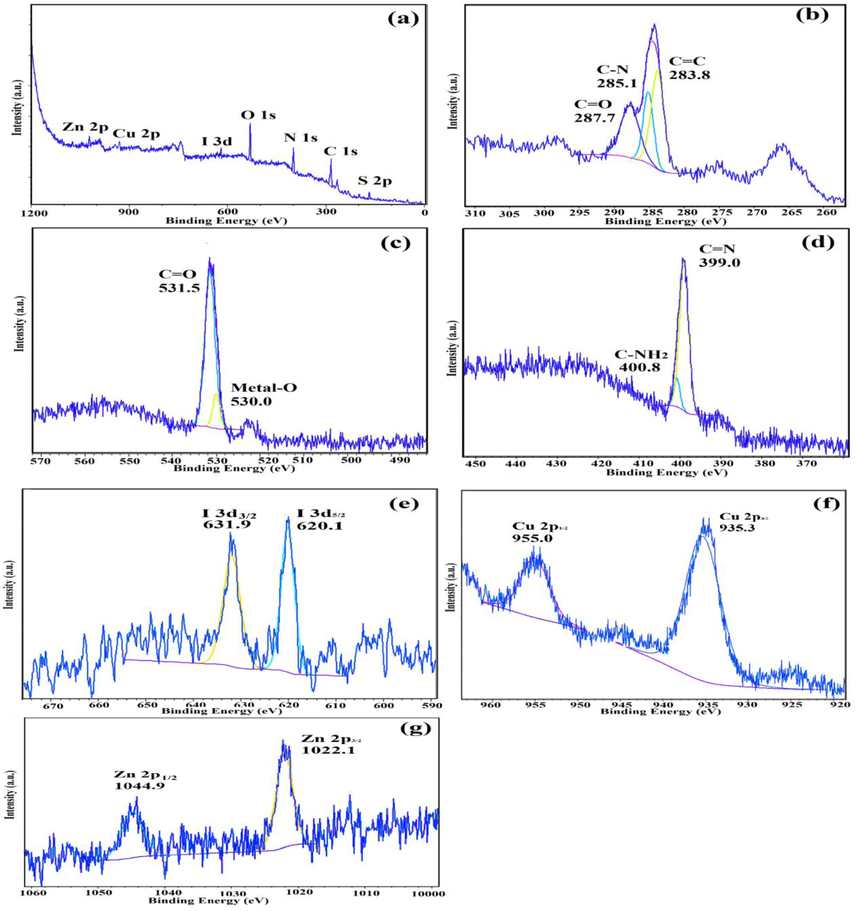

3.1.7 XPS analysis

The atomic oxidation states and chemical compositions of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu were investigated using XPS. According to XPS analysis (Fig. 12a), basic elements in IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu are Cu, I, C, O, N, S, and Zn, which is consistent with the EDS analysis results. According to Fig. 12b, the absorption peaks of C1 at binding energies of 287.7 eV, 285.1 eV, and 283.8 eV are assigned to C⚌C, C—N, and O⚌C—O, respectively, corresponding to amino terephthalate ligands. Fig. 12c indicates the spectrum of O 1s. Peaks at 530.0 eV and 531.5 eV correspond to M—O (M⚌Zn, Cu) and O⚌C—O, respectively. Two peaks at 399.0 eV and 400.8 eV correspond to the functional groups C—NH2 and C⚌N, respectively (Fig. 12d). The observed I 3d peaks in Fig. 12e are characteristic of CuI NPs (Fig. 12e). Moreover, Cu 2p spectrum indicates two strong peaks at 935.3 eV and 955.0 eV that are related to Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2, respectively (Fig. 12f). This observation provides a strong reason to prove the interaction of Cu(I) and IRMOF-3/PSTA. The peaks shown in Fig. 14g at 1044.9 eV and 1022.1 eV for Zn 2p in IRMOF-3 are characteristic of Zn 2p1/2 and Zn 2p3/2, respectively. Accordingly, it is confirmed that introducing porous PSTA and CuI NPs into IRMOF-3 resulted in successful surface functionalization.

XPS spectra of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu: (a) survey, (b) C 1s, (c) O 1s, (d) N 1s, (e) I 3d, (f) Cu 2p, and (g) Zn 2p.

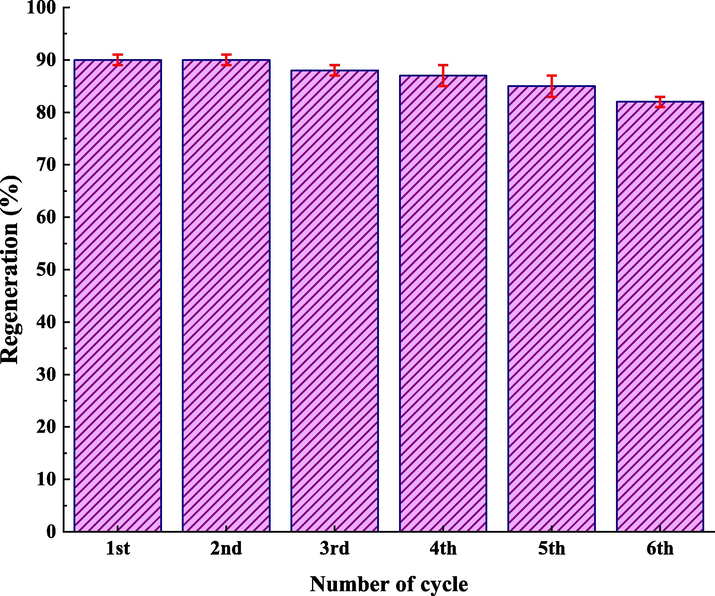

Reusability of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu in the synthesis of compound 4h.

The FT-IR spectrum and FESEM image of the reused catalyst after six recycles.

3.2 Catalytic studies

3.2.1 Effect of parameters

The prepared IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was examined in terms of its catalytic potential and the effects of temperature, catalyst, and solvent content on the model reaction. First, the three-component domino reaction of salicylaldehyde, morpholine, and phenylacetylene was studied in terms of catalytic activity in DMF at 100 ℃ (Table 2). Notably, the reaction yielded the desired product (entry 1). Afterward, we investigated the effect of the catalyst loading on the reaction (entries1-3), with the results presented in Table 2. The optimal MOF amount was determined to be 10 mg (entry 2), which yielded the highest amount of the product with the least catalyst use. This amount is 0.43 mol% Cu for IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu. When 10 mg of the catalyst was taken, the complete transformation of reactants occurred (based on yield) and the reaction efficiency was not improved by increasing the amount of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu beyond 10 mg. Based on the obtained results, conducting the reaction in the absence of the catalyst (Table 2, entry 4) led to no detectable amount of the composite. Next, the role of other solvents was tested by studying the model reaction through solvents such as toluene, EtOH, CH3CN, and solvent-free condition in the presence of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite (Table 2, entries 5–9). It is worth mentioning that the reaction efficiency was decreased using ethanol. Ethanol’s deactivating effect is also manifested through changes in the activation energy. Moreover, the decreased activity of the catalytic species is suggested to be caused by preferential solvation of them and reactant by ethanol. Also, ethanol reduces the progress of the reaction by establishing a hydrogen bond with the reactants. In the case of toluene, due to its toxicity and the low solubility of the synthesized catalyst in toluene as a solvent, the reaction proceeds with a lower rate, efficiency, and yield (entry 8). However, the results of these experiments showed the best reaction medium is DMF (Table 2, entry 2). The surface modification’s effect on the reaction progress was examined by investigating the model reaction in the presence of CuI NPs, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, IRMOF-3, IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu, IRMOF-3/CuI, UiO-66-NH2, and PSTA/CuI (Table 2, entries 10–16), and none of them produced satisfactory results. In addition to the effective metal-support synergistic interaction of copper and IRMOF-3/PSTA in the IRMOF-3/PSTA/CuI catalyst, the Lewis acidic nature of IRMOF-3 highly contributes to bringing the N-bearing heterocyclic substrate closer to the catalytic metal center (Cu) and hence promote the reaction rate. Introducing metal nanoparticles in these structures leads to the creation of bimetallic systems. As a result, it brings the synergistic effect of the metal nanoparticles introduced with the metal nodes in the MOF structure and enhances the catalytic activity. Also, IRMOF-3/PSTA support may promote copper metal particle dispersion on its surface, resulting in more active catalyst sites of the metal center. The results indicate the high sensitivity and selectivity of the prepared model due to the synergistic effect of Zn-cluster, PSTA, and CuI NPs. Finally, various temperatures were applied to make the model reaction (Table 2, entries 17–18). Overall, 100 ℃ can be considered the model reaction’s preferred temperature. Examining the reaction without a base revealed a reduction in reaction efficiency (Table 2, entry 19). Following the screening, the optimal result was achieved in the presence of 10 mg IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocatalyst with DMF as the solvent at 100 ℃.Table 3

Entry

Cat. (mg)

Solvent

Temperature (℃)

Time (h)

Yield (%)b

TOF(h−1)c

1

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (5)

DMF

100

1

79

89.77

2

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

DMF

100

1

91

103.4

3

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (20)

DMF

100

1

91

103.4

4

No catalyst

DMF

100

24

–

–

5

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

EtOH:H2O

reflux

1

58

65.9

6

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

Solvent-free

100

1

69

78.4

7

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

EtOH

reflux

1

75

85.22

8

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

Toluene

reflux

1

81

92.04

9

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

CH3CN

reflux

1

55

62.5

10

IRMOF-3 (10)

DMF

100

1

40

45.45

11

UiO-66-NH2 (10)

DMF

100

1

35

39.77

12

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (10)

DMF

100

1

trace

–

13

CuI NPs (10)

DMF

100

1

42

47.72

14

IRMOF-3/PSTA (10)

DMF

100

1

59

67.04

15

PSTA/Cu (10)

DMF

100

1

66

75

16

IRMOF-3/Cu (10)

DMF

100

1

79

89.77

17

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

DMF

80

1

84

95.45

18

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

DMF

120

1

91

103.4

19

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (10)

DMF

100

1

61

69.31

Entry

Substrate

Product

Time

(min)

Yield

(%)

Melting point

Masured

Litrature

1

90

86

162–163

New

2

60

92

172–173

New

3

45

94

180–182

New

4

60

94

190–190

New

5

120

93

202–204

New

6

120

90

155–158

New

7

120

88

187–189

New

8

50

88

121–122

Not reported

9

60

91

105–108

107–108 (Zhang et al., 2011)

10

120

87

58–60

57–59 (Sharghi et al., 2014)

11

45

90

185–186

185–188 (Abtahi and Tavakol, 2021)

12

60

95

76–78

74–75 (Sharghi et al., 2014)

Regarding catalytic performance and ICP analysis, IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu indicated a more intense catalytic activity than PSTA/Cu and IRMOF-3/Cu. In this study, the Cu contents of porous PSTA/Cu and IRMOF-3/Cu were 1.35 and 3.5%, respectively, which were lower than the Cu content of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (5.58%). This difference is probably because of the cooperative interaction of melamine, sulfonamide, and free carboxylate groups with Cu. These functional groups can stabilize CuI NPs via a stronger bonding interaction between Cu and polymer/MOF than between PSTA and IRMOF-3. The obtained results suggest the essential role of the hybridization of IRMOF-3 and PSTA in CuI NPs’ activation. The reaction was selective. The starting material is almost consumed such that no by-products were observed (based on yield).

3.2.2 Effect of different salicylaldehyde and amine derivatives on the catalytic activity of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu.

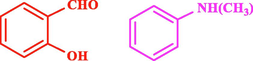

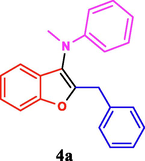

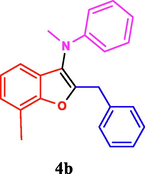

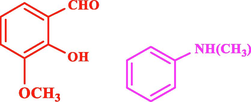

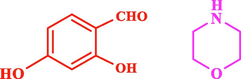

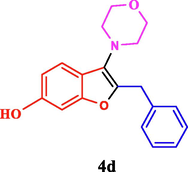

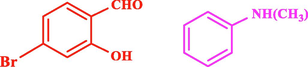

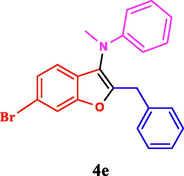

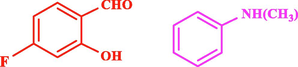

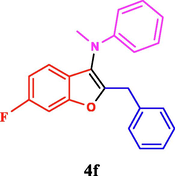

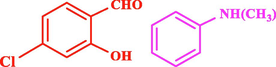

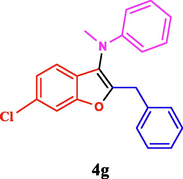

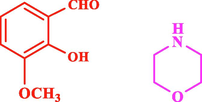

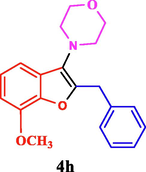

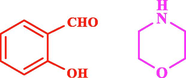

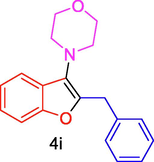

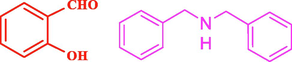

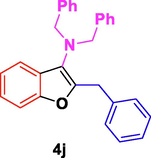

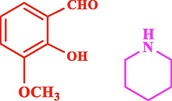

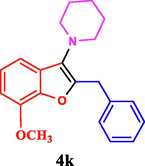

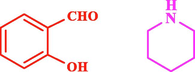

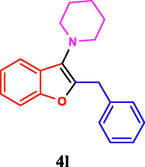

The general applicability of the IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was investigated using some salicylaldehydes, amines, and phenylacetylene substrates. The results showed an excellent turnover frequency (TOF) of the benzo[b]furan-forming reaction under optimized conditions and high yields. Whether the benzene ring of salicylaldehyde was substituted by electron-withdrawing groups (—H, —Cl, —Br, and —F) (4e, 4f, and 4g) or electron-donating (—OMe, —Me, —OH) (4b, 4c, and 4d), the corresponding products were obtained within 3.5–5.5 h in 77–90% yields. Based on the obtained results, salicylaldehyde’s electron-donating groups enhanced the IRMOF-3/PSTA-supported Cu-catalyzed domino reactions with higher reactivity than those containing electron-withdrawing groups and led to higher TOFs and yields. The results also showed the successful reactions of aliphatic amines (e.g., morpholine, piperidine, and dibenzylamine) with salicylaldehyde (4h, 4i, 4j. 4k, and 4l). Although the presented system is highly effective for secondary amines, the primary amine substrates (e.g., PhNH2) could not afford the desired benzofuran. Nevertheless, we prepared new benzo[b]furan, the first to report to our knowledge.

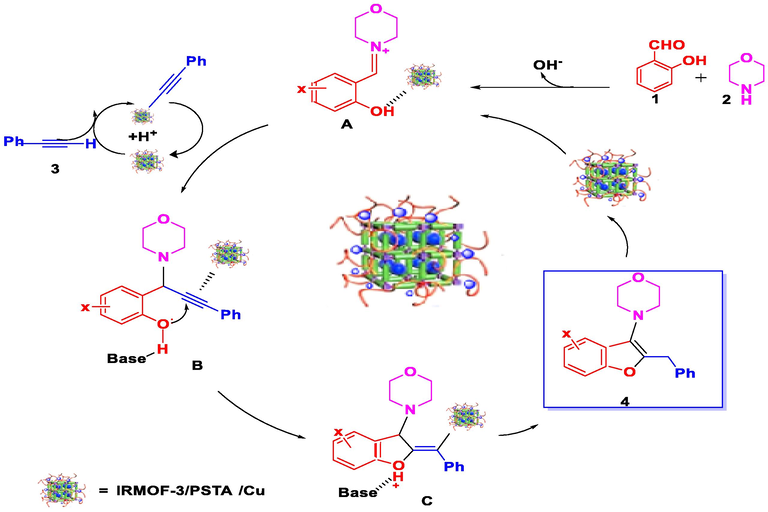

3.2.3 Reaction mechanism

Scheme 4 shows the mechanism offered for the one-pot preparation of benzofurans through a three-component domino reaction catalyzed by IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu. According to this figure, the IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu catalyst first enhances the activity of phenylacetylene binding to iminium ions generated in situ by the reaction between salicylaldehydes and amines (intermediate A). IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposites also promote cyclization through nucleophilic attack of hydroxyl groups (intermediate B). In the final step, as is evident in intermediate C, the corresponding product was obtained and the IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was recycled for further reactions (Abtahi and Tavakol, 2021; Safaei-Ghomi et al., 2016; Purohit et al., 2017; Sadjadi et al., 2018).

The possible mechanism for the synthesis of benzofuran derivatives.

3.2.4 Reusability of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocatalyst

The recyclability of catalyst materials is a crucial design parameter for a more economical process. Following completing the reaction, the catalyst was separated from the reaction system through centrifugation, washed it several times with water and ethanol, and dried it in a vacuum drying oven at 80 ℃ for compound 4 h. IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was reused for up to six cycles with negligible loss of catalytic activity such that products with high yields were obtained (90, 90, 88, 87, 85, 82%). The minor reduction observed in the catalytic ability is likely due to the normal dissipation of the catalyst in the workup process. These results indicate a negligible amount of catalyst leaching into the reaction mixture (Fig. 13).

In addition, the catalysts’ stability was proved by re-performing the FT-IR spectrum and FESEM image (Fig. 14). The outcomes confirm these catalysts’ stability. These patterns do not exhibit any changes after the initial patterns.

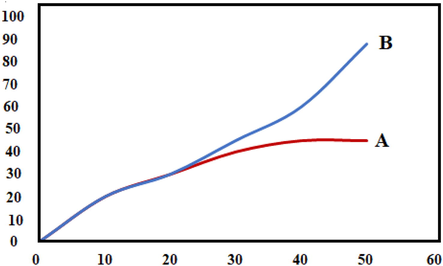

The filtration test for the reaction between 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, morpholine, and phenylacetylene using IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu as a catalyst was performed to check the leaching of CuI NPs during the reaction. A catalytic run was started for a standard reaction, and after the reaction for 25 min (the reaction was completed in 50 min), corresponding to 50% conversion, the reaction mixture was stopped and centrifuged to afford a clear filtrate. Then the mixture without the solid catalyst was treated as a standard catalytic run for another 25 min, and the conversion did not proceed significantly. The results were compared with that of a standard catalytic run. The results clearly show that after the removal of the heterogeneous catalyst, slow progression of the reaction was observed. This finding suggests that the prepared catalyst is stable and the leaching of CuI NPs species from the solid support is low (Fig. 15).

Hot-filtration test for IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu in the reaction of 2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, morpholine, and phenylacetylene: A) hot filtered test and (B) normal reaction.

3.2.5 Comparison activity of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu with other catalysts

The advantages of the produced nanocatalyst are summarized in Table 4 by comparing its properties with various catalytic systems used for producing 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans in the presence of different catalysts. According to these data, the catalytic system presented in this study offers higher efficiency than other systems for this reaction regarding the reaction yield and time. The advantages of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu as the catalyst in the system include a less intensive process, a high yield of 92%, and separability and recyclability several times, which are difficult to obtain using pure CuI NPs (entry 5).

Entry

Catalyst

Solvent

Conditions

Time

(min)

Yield (%)a

Ref.

1

h-Fe2O@SiO2-IL/Ag (25 mg)

H2O

r.t/ultrasound

10

92

(Sadjadi et al., 2018)

2

CuI (30 mol%)

CH3CN

Microwave

30

77

(Nguyen and Li, 2008)

3

CuI (20 mol%)

Toluene

110 °C

240

79

(Li et al., 2009)

4

CuI (5 mol%)

ChCl-EG

80 °C

420

80

(Abtahi and Tavakol, 2021)b

5

IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu (0.88 mol%)

DMF

K2CO3/100 °C

45

90

This work

4 Conclusion

We synthesized IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu nanocomposite by reaction of IRMOF-3 with porous PSTA followed by immobilization of CuINPs. The obtained solid was a combination of acidity of —NH groups, basicity, hydrogen bonding, and Lewis acidity of Zn4+ metal nodes and CuI NPs. This product was used as a heterogeneous active catalyst for different 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furan via the one-pot three-component reaction. The results showed the higher catalytic activity of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu than IRMOF-3, PSTA/Cu, IRMOF-3/PSTA, and UiO-66-NH2. The observed high catalytic activity might be due to the synergistic interaction between the unsaturated open Zn4+ sites, CuI NPs, and porous PSTA. Large surface area and high porosity are other important factors in catalytic activity. In addition, IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu was found as a multifunctional MOF with robustness and stability under reaction conditions. The advantages of performing the presented method in the presence of IRMOF-3/PSTA/Cu as a catalyst can be summarized as follows:

-

The catalyst can be reused up to six times without losing its catalytic activity and structural integrity.

-

Desired products are obtained in excellent yields under mild reaction conditions.

-

The catalyst is easily separated from the mixture by centrifugation and provides a great TOF.

-

The procedure involves an easy purification, synthesis of new compounds, and a short time. Overall, this research portrays a bright future for using porous MOFs and their functionalized analogs as multifunctional catalysts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Samaneh Koosha: Investigation, Doing laboratory work & preparing data. Samaneh Koosha: . Sedigheh Alavinia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Ramin Ghorbani-Vaghei: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bu-Ali Sina University, Center of Excellence Developmental of Environmentally Friendly Methods for Chemical Synthesis (CEDEFMCS) for financial supporting of this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- CuI-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of 3-aminobenzofurans in deep eutectic solvents. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2021;35:e6433.

- [Google Scholar]

- Copper iodide nanoparticles-decorated porous polysulfonamide gel: as effective catalyst for decarboxylative synthesis of N -Arylsulfonamides. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2020;34:e5449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeted development of hydrophilic porous polysulfonamide gels with catalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids.. 2020;146:109573

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cu(II) immobilized on poly(guanidine-sulfonamide)-functionalized Bentonite@MgFe2O4: a novel magnetic nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole. RSC Adv.. 2023;13:10667-10680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrophobic ion pairing with cationic derivatives of α-, ß-, and γ-cyclodextrin as a novel approach for development of a self-nano-emulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) for oral delivery of heparin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm.. 2021;47:1809-1823.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MOF derived nano-materials: a recent progress in strategic fabrication, characterization and mechanistic insight towards divergent photocatalytic applications. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2022;456:214392

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Last decade of unconventional methodologies for the synthesis of substituted benzofurans. Molecules.. 2020;25:2327.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-organic framework (MOF)-, covalent-organic framework (COF)-, and porous-organic polymers (POP)-catalyzed selective C-H bond activation and functionalization reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2022;51:7810-7882.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent Advances in the Cycloaddition Reactions of 2-Benzylidene-1-benzofuran-3-ones, and Their Sulfur, Nitrogen and Methylene Analogues. Chem. - An Asian J.. 2020;15:2838-2853.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Advances in synthetic strategies and medicinal importance of benzofurans: a review. Asian J. Org. Chem.. 2022;11

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of cefxime and lamotrigine on HKUST–1/ZIF–8 nanocomposite: isotherms, kinetics models and mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2023;20:1645-1672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethylene diamine grafted nanoporous UiO-66 as an efficient basic catalyst in the multicomponent synthesis of 2-aminithiophenes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018;32:e4307.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalyst-Incorporated cross-linked porous polymer networks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2022;61:10616-10630.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural investigation of graphitic carbon nitride via XRD and neutron diffraction. Chem. Mater.. 2015;27:2612-2618.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polymer-metal-organic framework hybrids for bioimaging and cancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2022;456:214393

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- γ-Fe2O3@Cu-Al-LDH/HEPES a novel heterogeneous amphoteric catalyst for synthesis of annulated pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidines. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2022;36:e6823.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of Fe3O4@GlcA@Ni-MOF composites as environmentally green catalyst in organic reactions. Environ. Technol. Innov.. 2021;24:102050

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fe3O4@SiO2@propyl-ANDSA: a new catalyst for the synthesis of tetrazoloquinazolines. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2018;32:e4038.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent Progress in the synthesis of 2-Benzofuran-1(3H)-one. Chinese J. Org. Chem.. 2022;42:1085-1100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Copper-based polymer-metal–organic framework embedded with Ag nanoparticles: Long-acting and intelligent antibacterial activity and accelerated wound healing. Chem. Eng. J.. 2022;435:134915

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Powerful direct C-H amidation polymerization affords single-fluorophore-based white-light-emitting polysulfonamides by fine-tuning hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2022;144:1778-1785.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel synthesis of aromatic polysulfonamides from active DI-1-benzotriazolyl disulfonate and aromatic diamine under mild conditions. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Lett.. 1977;15:207-211.

- [Google Scholar]

- HPA-dendrimer functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O 4@D-NH2 -HPA) as a novel inorganic-organic hybrid and recyclable catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of highly substituted pyran derivatives. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2018;209:46-59.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Post-synthetic modification of IR-MOF-3 as acidic-basic heterogeneous catalyst for one-pot synthesis of pyrimido[4,5-b]quinolones. Res. Chem. Intermed.. 2022;48:1773-1792.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magnetically recoverable catalysts: catalysis in synthesis of polyhydroquinolines. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2020;34:e5400.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel cubic Zn-citric acid-based MOF as a highly efficient and reusable catalyst for the synthesis of pyranopyrazoles and 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2022;36:e6656.

- [Google Scholar]

- CuI nanoparticle-immobilized on a hybrid material composed of IRMOF-3 and a sulfonamide-based porous organic polymer as an efficient nanocatalyst for one-pot synthesis of 2,4-diaryl-quinolines. RSC Adv.. 2023;13:11480-11494.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Benzofuran: a key heterocycle - Ring closure and beyond. Mini. Rev. Org. Chem.. 2020;17:224-276.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New domino approach for the synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans via copper-catalyzed multicomponent coupling reactions followed by cyclization. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2009;50:2353-2357.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic promotion of the photocatalytic efficacy of CuO nanoparticles by heteropolyacid-attached melem: robust photocatalytic efficacy and anticancer performance. Appl. Organometallic Chem.. 2022;36:e6878.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesized CuO as a Green and Efficient Nanophotocatalyst in the Solvent-Free Synthesis of Some Chromeno[4, 3-b]Chromenes. Studying anti- Gastric Cancer Activity, Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 2022;42:7071-7090.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A general post-synthetic modification approach of amino-tagged metal–organic frameworks to access efficient catalysts for the Knoevenagel condensation reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A.. 2015;3:17320-17331.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of metalloporphyrin-based porous organic polymers and their functionalization for conversion of CO2 into cyclic carbonates: Recent advances, opportunities and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A.. 2021;9:25731-25749.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polymer@MOF@MOF: “grafting from” atom transfer radical polymerization for the synthesis of hybrid porous solids. Chem. Commun.. 2015;51:11994-11996.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Advances in porous organic polymers: Syntheses, structures, and diverse applications. Mater. Adv.. 2022;3:707-733.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hercynite silica sulfuric acid: a novel inorganic sulfurous solid acid catalyst for one-pot cascade organic transformations. RSC Adv.. 2022;12:26023-26041.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmite nanoparticles as versatile support for organic–inorganic hybrid materials: Synthesis, functionalization, and applications in eco-friendly catalysis. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2021;97:1-78.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent Developments in C−H Functionalisation of Benzofurans and Benzothiophenes. European J. Org. Chem.. 2021;2021:1072-1102.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Encapsulation of Allopurinol in GO/CuFe2O4/IR MOF-3 Nanocomposite and In Vivo Evaluation of Its Efficiency. J. Pharm. Innov. 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Organic-inorganic hybridization of isoreticular metal-organic framework-3 with melamine for efficiently reducing the fire risk of epoxy resin. Compos. Part B Eng.. 2021;211:108606

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent Dearomatization Strategies of Benzofurans and Benzothiophenes. Asian J. Org. Chem.. 2021;10:932-948.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient synthesis of dihydrobenzofurans via a multicomponent coupling of salicylaldehydes. Amines, and Alkynes, Synlett.. 2008;2008:1897-1901.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ordered macroporous MOF-based materials for catalysis. Mol. Catal.. 2022;529:112568

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hierarchically Porous Sphere-Like Copper Oxide (HS-CuO) nanocatalyzed synthesis of benzofuran isomers with anomalous selectivity and their ideal green chemistry metrics. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2017;5:6466-6477.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dysprosium–balsalazide complex trapped between the functionalized halloysite and g -C 3 N 4: A novel heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of annulated chromenes in water. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2022;36:e6829.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microporous hierarchically Zn-MOF as an efficient catalyst for the Hantzsch synthesis of polyhydroquinolines. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12:1479.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive review on water remediation using UiO-66 MOFs and their derivatives. Chemosphere.. 2022;302:134845

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microwave-Assisted desulfonylation of polysulfonamides toward polypropylenimine. ACS Macro Lett.. 2018;7:598-603.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green bio-based synthesis of Fe2O3@SiO2 -IL/Ag hollow spheres and their catalytic utility for ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of propargylamines and benzo[b ]furans. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2018;32:e4029.

- [Google Scholar]

- CuI-nanoparticles-catalyzed one-pot synthesis of benzo[b ]furans via three-component coupling of aldehydes, amines and alkyne. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2016;20:502-509.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- One-pot Synthesis of Pyranoquinoline Derivatives Using a New Nanomagnetic Catalyst Supported on Functionalized 4-Aminopyridine (AP) Silica. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2020:402-409.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Solvent-free and one-pot strategy for ecocompatible synthesis of substituted benzofurans from various salicylaldehydes, secondary amines, and nonactivated alkynes catalyzed by copper(I) oxide nanoparticles. Synth.. 2014;46:2489-2498.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and Application of Highly Efficient and Reusable Nanomagnetic Catalyst Supported with Sulfonated-Hexamethylenetetramine for Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-Ones. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd.. 2022;42:2410-2419.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study on the delivery of some common drugs by ZIF-67, ZIF-90, and ZIF-8 zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35:e6377.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phosphotungstic acid grafted zeolite imidazolate framework as an effective heterogeneous nanocatalyst for the one-pot solvent-free synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e4959.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts in olefin epoxidation and carbon dioxide cycloaddition. Inorganics.. 2021;9:81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NiO@TPP-HPA as an Efficient Integrated Nanocatalyst and Anti-Liver Cancer Agent. Synthesis of 2-Substituted Indoles. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 2D MOFs and their derivatives for electrocatalytic applications: Recent advances and new challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2022;472:214777

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porous organic polymers in solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2022;51:4465-4483.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porous organic polymers for light-driven organic transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2022;51:2444-2490.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- CuI/[bmim]OAc in [bmim]PF6: A highly efficient and readily recyclable catalytic system for the synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted benzo[b]furans. Catal. Commun.. 2011;12:839-843.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Organocatalytic synthesis of polysulfonamides with well-defined linear and brush architectures from a designed/synthesized Bis(N-sulfonyl aziridine) Macromolecules. 2021;54:8164-8172.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The use of Nafion-H®/NaNO2 as an efficient procedure for the chemoselective N-nitrosation of secondary amines under mild and heterogeneous conditions. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2003;44:3345-3349.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104975.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1