Translate this page into:

Cyclohexylethanoid derivative and rearranged abietane diterpenoids with anti-inflammatory activities from Clerodendrum bungei and C. inerme

⁎Corresponding authors at: State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology, College of Pharmacy and Tianjin Key Laboratory of Molecular Drug Research, Nankai University, Haihe Education Park, 38 Tongyan Road, Tianjin 300353, People’s Republic of China. xiechunfeng@nankai.edu.cn (Chunfeng Xie), cheng.yang@nankai.edu.cn (Cheng Yang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

One new dimeric cyclohexylethanoid derivative (1) and one new rearranged abietane diterpenoid (2) were isolated from Clerodendrum bungei and C. inerme, respectively, together with 11 known compounds. The structures of the isolated compounds were elucidated by detailed spectroscopic and ECD analyses. The absolute configuration of 2 was unequivocally determined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Compound 1 showed the greatest inhibitory effect on NO production in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with the IC50 value of 6.328 µM. Compound 1 also suppressed the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS and IL-6 mRNA expression, while increased the mRNA expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10 and Arg-1 through NF-κB signaling pathway. The further experiments confirmed that compound 1 demonstrated the strong in vivo anti-inflammatory effect by reducing mortality, the serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ levels, and tissue toxicity in CLP-induced septic mice. Collectively, these findings suggested that compound 1 might serve as a potential anti-inflammatory agent candidate for the sepsis treatment.

Keywords

Clerodendrum bungei

Clerodendrum inerme

Cyclohexylethanoid derivatives

Rearranged abietane diterpenoids

Anti-inflammatory effect

Sepsis

1 Introduction

Sepsis may be a general inflammatory response to microorganism infection, and it is additionally one in all the vital causes of death and enhanced medical prices in modern intensive care units (Singer et al., 2016). Despite enhanced drug resistance, antibiotic use and organ support are still the most common strategies, and have a restricted impact on the prognosis of patients with infection (Gauer et al., 2020). Finding effective treatment for sepsis is an imperative for human health.

Inflammation imbalance is the most crucial basis during the pathologic process of sepsis. The pathogens inflicting inflammation consist of bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses (Huang et al., 2019). Sepsis-induced immunological disorder is due to the destruction of immune physiological condition. Its characteristics involve the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Liu et al., 2022).

The genus Clerodendrum, belonging to the family of Verbenaceae, are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions with different growth habits of small trees, shrubs, vines and herbs (Editorial Committee of the Flora of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1982). In addition to growing as ornamental plants, some Clerodendrum species have been reported to possess insecticidal and medicinally therapeutic properties (Kuźma and Gomulski, 2022; Wang et al., 2017). C. bungei and C.inerme were both used to treat skin diseases, rheumatic pain, arthritis, and other inflammation-related diseases (Compilatory Group of Compilation of Chinese Herbal Medicine, 1996). Phytochemical studies on C. bungei or C. inerme revealed the various constituents including diterpenoids, cyclohexylethanoids, phenylethanoids, perhydrobenzofurans, flavonoids, triterpenoids, sterols, megastigmane and iridoid glucosides (Kanchanapoom et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Pandey et al., 2003; Parveen et al., 2010; Srisook et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2002). Recently studies have shown that C. bungei, C. inerme or their secondary metabolites had various pharmacological effects, such as anti-tumor (Liu et al., 2009), anti-complement (Kim et al., 2010), antioxidant (Ba Vinh et al., 2018), hepatoprotective (Gopal et al., 2008), anti-inflammatory (Srisook et al., 2015), α-glucosidase and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory activities (Liu et al., 2014).

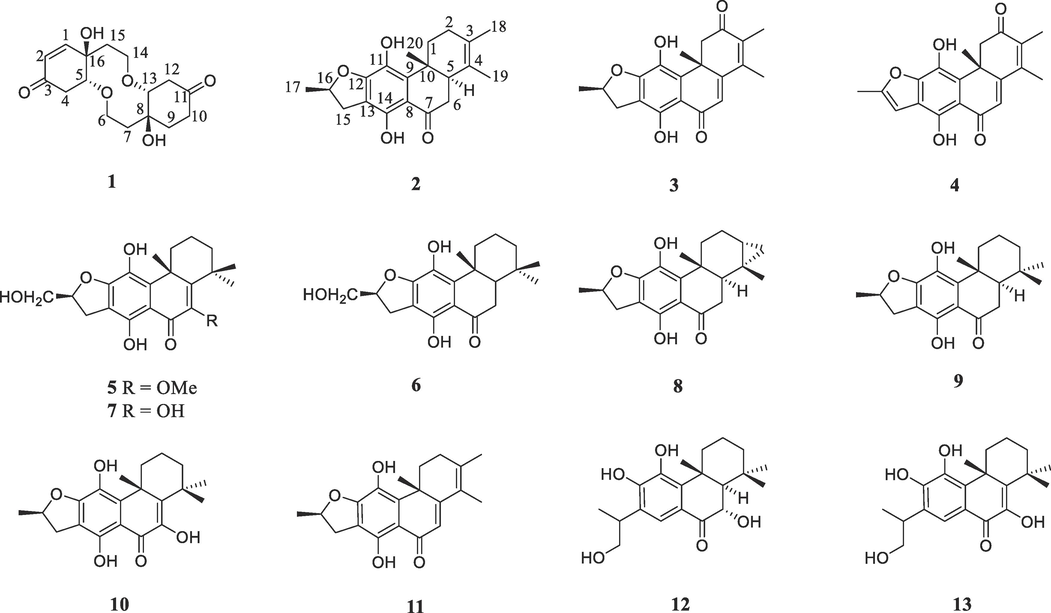

In our ongoing search for bioactive ingredients from the medicinal plants, the chemical constituents of C. bungei and C. inerme were investigated. Thirteen compounds, including one new dimeric cyclohexylethanoid derivative and one new abietane diterpenoid, were obtained (Fig. 1) and their anti-inflammatory effects were evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Herein, the isolation, structure elucidation, the in vitro anti-inflammatory testing of all compounds, as well as the in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of compound 1 in CLP-induced septic mice were reported.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–13.

2 Experimental section

2.1 General experimental procedures

The material and instruments for the isolation and identification of compounds 1–13 were the same as reported (Ding et al., 2020).

2.2 Plant material

The branches and leaves of C. bungei and C. inerme were collected in December 2019 from Neijiang city of Sichuan Province and in November 2020 from Kunming city of Yunnan Province, China, respectively. The botanical identification was conducted by one of the authors (C.X.), and the two voucher specimens (No. 201912CB and 202011CI) were deposited at College of Pharmacy, Nankai University, China.

2.3 Extraction and isolation

The branches and leaves of C. bungei (5 kg) were extracted by refluxing with MeOH three times, followed by methanol elimination under reduced pressure to obtain a residue (775 g). The residue was suspended in water and then partitioned with EtOAc to yield a crude fraction (120 g), which was subjected to a silica gel column eluted with petroleum ether/acetone (100:0–100:30) to obtain five fractions (F1–F5). Fraction F3 (2.7 g) was isolated by medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) over ODS eluted with 75% and 85% MeOH in H2O, resulting in five subfractions F3a–F3e. Compounds 3 (tR = 23 min, 6.7 mg) and 4 (tR = 29 min, 10.8 mg) were isolated from the subfraction F3b by preparative HPLC (80% MeOH in H2O). Fraction F4 (4.5 g) gave six subfractions F4a– F4f on the basis of the same MPLC (75–85% MeOH in H2O). Compound 1 (tR = 10 min, 161.8 mg) was purified from the subfraction F4a using preparative HPLC (55% MeOH in H2O), while compounds 5 (tR = 28 min, 16.9 mg) and 6 (tR = 35 min, 7.1 mg) were obtained from the subfraction F4c based on HPLC (80% MeOH in H2O). Furthermore, the subfraction F4e was isolated by preparative HPLC (75% MeOH in H2O) to give compound 7 (tR = 82 min, 7.4 mg).

The branches and leaves of C. inerme (7.5 kg) were subjected to methanol extraction by refluxing three times and then methanol was removed under reduced pressure to obtain the crude extract (1100 g), which was subsequently suspended in H2O and partitioned with EtOAc. The resulting EtOAc-soluble part (155 g) was subjected to a column of silica gel eluted with petroleum ether/acetone (100:0–100:30) to obtain seven fractions (F1–F7). Fraction F2 (8.4 g) was isolated by medium-pressure liquid chromatography (MPLC) over ODS eluted with 75% to 85% MeOH in H2O to give five subfractions F2a–F2e. F2c was purified by preparative HPLC (80% MeOH in H2O) to afford compounds 8 (tR = 61 min, 4.7 mg), 2 (tR = 65 min, 3.3 mg), 9 (tR = 66 min, 9.4 mg) and 10 (tR = 81 min, 10.9 mg). Fraction F3 (13.1 g) provided seven subfractions F3a − F3g by the same MPLC (75–85% MeOH in H2O). F3b yielded compound 11 (tR = 53 min, 15.6 mg) through HPLC (75% MeOH in H2O). Fraction F4 (10.2 g) was purified on the MPLC (75–85% MeOH in H2O) to afford seven subfractions F4a − F4g. The subsequent purification of F4b using preparative HPLC (71% MeOH in H2O) gave compounds 12 (tR = 95 min, 38.9 mg) and 13 (tR = 197 min, 30.8 mg).

2.3.1 Clerodenone B (1)

Rufous oil; [α] − 12.515 (c 0.08, CH2Cl2); ECD (CH3CN) 204 (Δε + 1.15) nm, 219 (Δε + 0.79) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2959, 2924, 2856, 1713, 1682, 1455, 1378, 1260, 1092, 1065, 1018, 799, 704, 662, 589 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD) data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 333.1312 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C16H22O6Na 333.1314).

Position

1

2

δH mult (Hz)

δC

δH mult (Hz)

δC

1

6.79 dd (1.6, 10.2)

149.3

α 3.32 m; β 1.56 m

31.7

2

5.96 d (10.2)

127.4

α 1.99 m; β 1.25 m

29.8

3

197.8

124.0

4

α 2.79 m; β 2.58 m

38.9

127.0

5

4.14 td (1.6, 4.5)

80.8

2.73 d (15.5)

44.6

6

3.84 m; 3.94 m

65.5

α 2.49 m; β 2.83 m

37.5

7

2.54 m; 2.75 m

39.1

204.1

8

76.5

110.6

9

2.08 m

32.7

137.7

10

α 2.45 m; β 2.19 m

34.5

38.2

11

211.4

131.6

12

α 2.48 m; β 2.76 m

41.7

156.2

13

3.89 m

83.4

110.6

14

3.84 m; 4.02 m

65.7

155.8

15

2.23 m

39.5

α 2.83 m; β 3.37 m

34.3

16

74.1

5.12 m

83.3

17

1.51 d (6.3)

21.9

18

1.66 s

19.2

19

1.63 s

15.5

20

1.21 s

16.3

2.3.2 15,16-dihydrouncinatone (2)

Yellow crystal; [α] 22.686 (c 0.05, CH2Cl2); ECD (CH3CN) 221(Δε + 2.98) nm, 297 (Δε − 1.00) nm, 323 (Δε + 1.02) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3272, 2955, 2923, 2856, 1716, 1635, 1608, 1452, 1404, 1355, 1258, 1186, 1144, 1089, 1016, 962, 910, 880, 806, 718, 647, 586, 480 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 327.1601 [M − H]− (calcd for C20H23O4 327.1596).

2.4 ECD calculation

ECD spectrum was determined on a MOS-450CD spectrometer (BioLogic, France) and ECD calculation was carried out as previously reported (Ma et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2020).

2.5 X-ray crystal structure analysis

The crystallographic data were measured on a Rigaku XtalAB PRO MM007 DW diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. Tetragonal, space group P43, a = 8.43293(17) Å, b = 8.43293(17) Å, c = 23.1641(9) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, Z = 4, V = 1647.30(9) Å3, density (calculated) = 1.324 mg/m3, F(0 0 0) = 704, μ(Cu Kα) = 1.54184 mm−1, Flack parameter = − 0.12 (16), crystal size = 0.11 × 0.09 × 0.09 mm3, reflections collected: 7984, Independent reflections: 3248 [R(int) = 0.0432], R1 = 0.0423, wR2 = 0.1077, Final R1 = 0.0423, wR2 = 0.1077 (I > 2sigma(I)).

2.6 RAW 264.7 cell culture and nitrite determination

RAW 264.7 cells were purchased from the Procell Life Science&Technology Co., Ltd. The experimental procedures were the same as previously reported (Cheng et al., 2023).

2.7 Cell viability assay

The method for assessing the cell viability was similar as previously described (Cheng et al., 2023). The detailed procedure was provided in the Supporting Information.

2.8 Western blot assays

The western blot assays were carried out as reported (Cheng et al., 2023). The following antibodies were used: IκB-α (AF5002, Affinity), p-IκB-α (AF2002, Affinity), NF-κB p65 (AF5006, Affinity), NF-κB p-p65 (AF2006, Affinity) and β-tubulin (T0023, Affinity).

2.9 RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

The methods for the total RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis were the same as previously described (Cheng et al., 2023). The primers used for SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR were as follows:: IL-1β, 5′-AGCTTCAGGC AGGCAGTATC-3′ (Forward) and 5′-AAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC-3′ (Reverse); IFN-γ, 5′-TGA ACGCTACACACTGCATCT-3′ (Forward) and 5′-TGTTGCTGATGGCCTGATTGT-3′ (Reverse); iNOS, 5′-GGGCTGACCTGTTTCCT ACT-3′ (Forward) and 5′-GGAGGTTGAGACCCAATGGA-3′ (Reverse); IL-6, 5′-CAACGATGATGCACTTGCAGA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-TGTGACTCCAGCTTA TCTCTTGG-3′ (Reverse); TNF-α, 5′-CC CACGTCGTAGCAAACCA-3′ (Forward) and 5′-ACAAGGTACAACCCATCGGC-3′ (Reverse); IL-4, 5′-GGCAGGAGAACATGGAGAGT-3′ (Forward) and 5′-CTTTCCTTCCTGCCTCTCCA-3′ (Reverse); IL-10, 5′-TAACTGCACCCACTTCCCAG-3′ (Forward) and 5′-AAGGCTTGGCAACCCAAGTA-3′ (Reverse); Arg-1, 5′-CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG-3′ (Forward) and 5′-GGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATCA-3′ (Reverse); β-actin, 5′-TGAGCTGCGTT TTACACCCT-3′ (Forward) and 5′-GCCTTCACCGTTCCAGTTTT-3′ (Reverse); GAPDH, 5′-GGACTTA CAGAGGTCCGCTT-3′ (Forward) and 5′-CTATAGGGCCTGGGTCAGTG-3′ (Reverse). Mean Ct of each gene was determined from triplicate measurements and normalized with the mean Ct of GAPDH or β-actin, a control gene.

2.10 Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (weight 19–21 g) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All animal experiments have been approved by the Animal Protection and Use Committee of Nankai University (No. 2022-SYDWLL-000586) and followed Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. Mice were classified into five groups (n = 8 for each): Sham group, CLP group, CS group (CLP + intraperitoneal injection of Cefpirome sulfat, 200 mg/kg each time), low-dose group (CLP + intraperitoneal injection of compound 1, 5 mg/kg each time) and high-dose group (CLP + intraperitoneal injection of compound 1, 15 mg/kg each time). After mice were acclimatized to the laboratory conditions for 7 days, multibacillary sepsis was stimulated by CLP method. The mice were administered at 2 h before and 24 h after CLP. The H&E staining was carried out according to the previous procedure (Cheng et al., 2023).

2.11 ELISA assay

Blood samples were collected from five groups at 48 h post-surgery and then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Serum was collected and stored at − 20 °C before subjecting to further analysis. The levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ were determined using ELISA kits (Jianglai Biological Technology, Shanghai, China) by reading the absorbance at 450 nm.

2.12 Statistical analysis

Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad) for statistical comparison, two-tailed student T test to compare two data sets, and ANOVA for multiple comparison were performed, respectively. The statistical significance was considered based on P value < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural elucidation

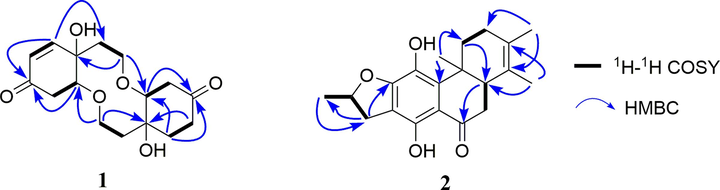

Compound 1 was isolated as rufous oil. Its HR-ESIMS showed an [M + Na] + peak at m/z 333.1312, indicating the molecular formula of C16H22O6 (calcd for C16H22O6Na 333.1314) and six degrees of unsaturation. The IR data revealed hydroxyl (3376 cm−1), carbonyl (1717 cm−1) and double bond (1682 cm−1) functional groups. The 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1) displayed the presence of two olefinic methines at δH 5.96 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H) and 6.79 (dd, J = 1.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), two oxygenated methines at δH 4.14 (td, J = 1.6, 4.5 Hz) and 3.89 (m, 1H), and two oxygenated methylenes at δH 3.84 (m, 2H), 3.94 (m, 1H), 4.02 (m, 1H). The 13C NMR spectrum (Table 1) of 1 showed 16 carbon signals consisting of eight methylenes [two oxymethylenes (δC 65.7, 65.5)], four methines [two oxymethines (δC 80.8 and 83.4) and two olefinic methines (δC 127.4 and 149.3)], and four quaternary carbons [two ketone carbonyl (δC 197.8, 211.4) and two oxygenated tertiary carbon (δC 74.1, 76.5)] on the basis of the DEPT and HMQC spectra. Since three degrees of unsaturation were assignable to two ketone carbonyl and one double bond groups, the remaining ones were thus attributed to three saturated rings. The NMR data of 1 indicated a resemblance with those of the known compound clerodenone A also occurring in C. bungei (Liu et al., 2009) except for the appearance of two aliphatic methylenes (δC 32.7, 34.5) instead of the double bond carbons (δC 148.8, 128.1), as evidenced by 1H–1H COSY correlations and HMBC correlation (Fig. 2). Thus, the planar structure of 1 was determined to be that depicted.

1H–1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

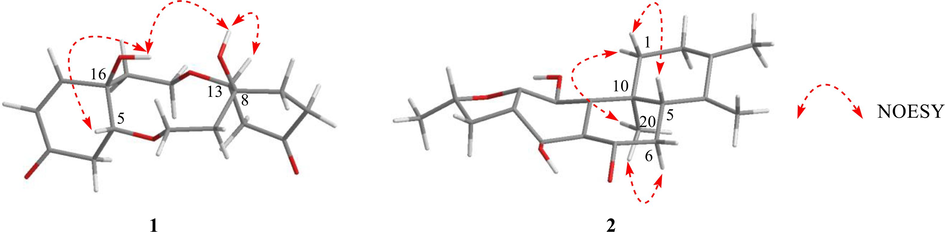

The NOESY correlations of HO-8/H-13 and HO-16/H-5 (in DMSO‑d6) (Fig. 3), as well as the small coupling, implied a relative cis orientation (Liu et al., 2009). Furthermore, the NOESY correlation of HO-8 and HO-16 revealed that HO-8, H-13, HO-16 and H-5 were all the same orientation and assigned as a β-orientation. The calculated ECD spectrum matched the experimental data closely (Figure S10), demonstrating a (5R, 8S, 13R, 16R) absolute configuration for 1. Compound 1 is thus established and named clerodenone B.

Selected NOESY correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

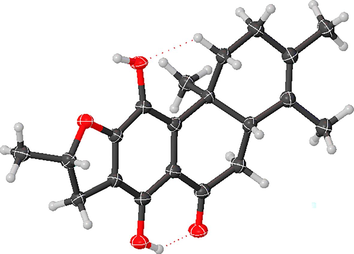

The molecular formula of compound 2 was deduced to be C20H24O4 according to the negative ion peak at m/z 327.1601 [M − H]– (calcd for C20H23O4 327.1596) in HR-ESIMS spectrum with the 9 degrees of unsaturation. Four methyl signals at δH 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.51 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 1.63 (s, 3H), and 1.66 (s, 3H), one oxygenated methine at δH 5.12 (m, 1H), and one characteristic signal of a hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl group at δH 13.44 (s, 1H) were observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1). The 13C NMR spectrum displayed 20 carbon signals, which were divided into one carbonyl carbon at δC 204.1, eight sp2 quaternary carbons, one sp3 quaternary carbon, four sp3 methylenes, two sp3 methines and four methyl groups with the aid of DEPT and HMQC spectra. This suggested that 2 might be a 17(15 → 16), 18(4 → 3)-diabeo-abietane diterpenoid (Fan et al., 2000), and was structurally similar to the known compound uncinatone (11) (Tian et al., 1993) except for the shielded resonances at C-5 (ΔδC − 125.3 ppm) and C-6 (ΔδC − 85.9 ppm). Combined with the 1H–1H COSY correlations of H-5/H2-6 and the HMBC interactions of H-6/C-7 and C-10, compound 2 was inferred to be a 5, 6-dihydro derivative of uncinatone. The complete planar structure of 2 was established by the detailed interpretation of 1H–1H COSY and HMBC spectra (Fig. 2). The NOESY correlations of H-5/H-1β, H-1α/H3-20, and H-6α/H3-20 suggested that the A/B rings are trans-fused (Fig. 3). X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC 2160720) of 2 determined the absolute configuration as 5S,10R,16S (Fig. 4). Thus, the structure of 2 was identified as (5S,10R,16S)-12,16-epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-17(15 → 16), 18(4 → 3)- diabeo-abieta-3,8,11,13-tetraen-7-one and named 15,16-dihydrouncinatone.

X-ray crystallographic structure of 2.

The known compounds were identified as teuvincenone E (3) (Rodríguez et al., 2002), teuvincenone F (4) (Cuadrado et al., 1992), 6-methoxyvillosin C (5) (Wang et al., 2013), villosin B (6) (Li et al., 2014), villosin C (7) (Li et al., 2014), teuvincenone D (8) (Rodríguez et al., 2002), villosin A (9) (Chen et al., 2017), teuvincenone B (10) (Ulubelen et al., 1994), uncinatone (11) (Tian et al., 1993), 6α,11,12,16-Tetrahydroxy-7-oxo-abieta-8,11,13-triene (12) (Yadav et al., 2010), and 6,11,12,16-tetrahydroxy-5,8,11,13- abitetetraen-7-one (13) (Han et al., 2008), respectively, be means of spectral data.

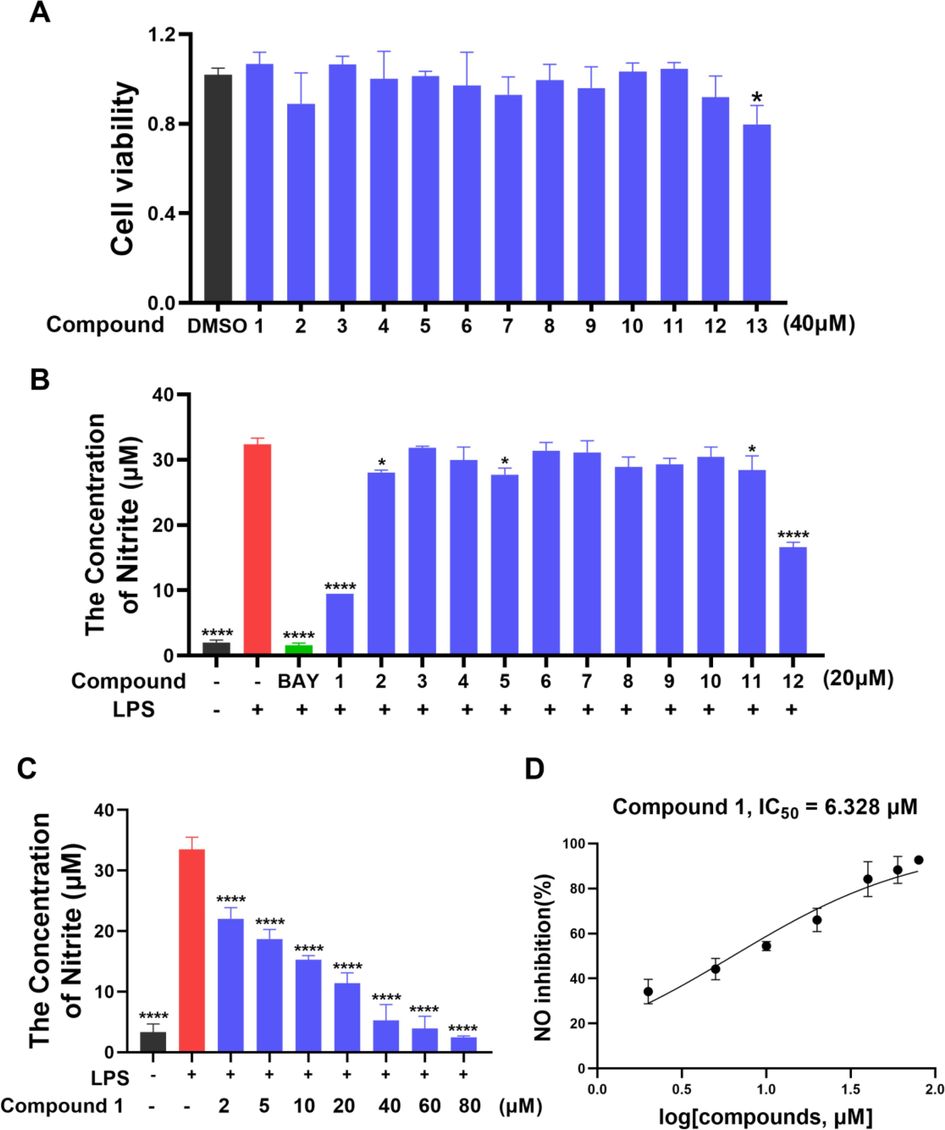

3.2 Anti-inflammatory effect of compounds 1–13 on LPS-activated NO production

The cytotoxicity of all the isolates 1–13 on RAW 264.7 cells was firstly assessed by Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) assay. As exhibited in Fig. 5A, all compounds except 13 have no significant toxicity on RAW 264.7 macrophages in vitro. Next, the inhibitory effects of 1–12 on NO generation in LPS (1 µg/ml)-mediated RAW 264.7 cells were examined, where BAY 11–7082 (BAY, 4 µg/ml) was used as a positive control. The anti-inflammatory result showed that compounds 1 and 12 significantly restrained the LPS-stimulated production of pro-inflammatory factor NO (Fig. 5B).

(A) Cell viability of RAW 264.7 cells treated with compounds 1–13 (40 μM). (B) NO production in LPS-mediated RAW 264.7 macrophages after compounds 1–12 treatment (20 μM). (C-D) Different concentrations treatment and the IC50 value of compound 1 against LPS-mediated NO production in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001, compared with the LPS group.

Due to low cytotoxicity (Fig. S41) and the greatest NO inhibitory activity in vitro, compound 1 was used to further investigate the anti-inflammatory activity. Cells were treated with different concentrations of 1 for 30 min followed by a 24 h treatment with LPS (1 µg/ml). The elevated NO levels stimulated by LPS were reduced significantly by pre-treatment with compound 1 in a dose-dependent fashion with the IC50 value of 6.33 μM (Fig. 5C-5D).

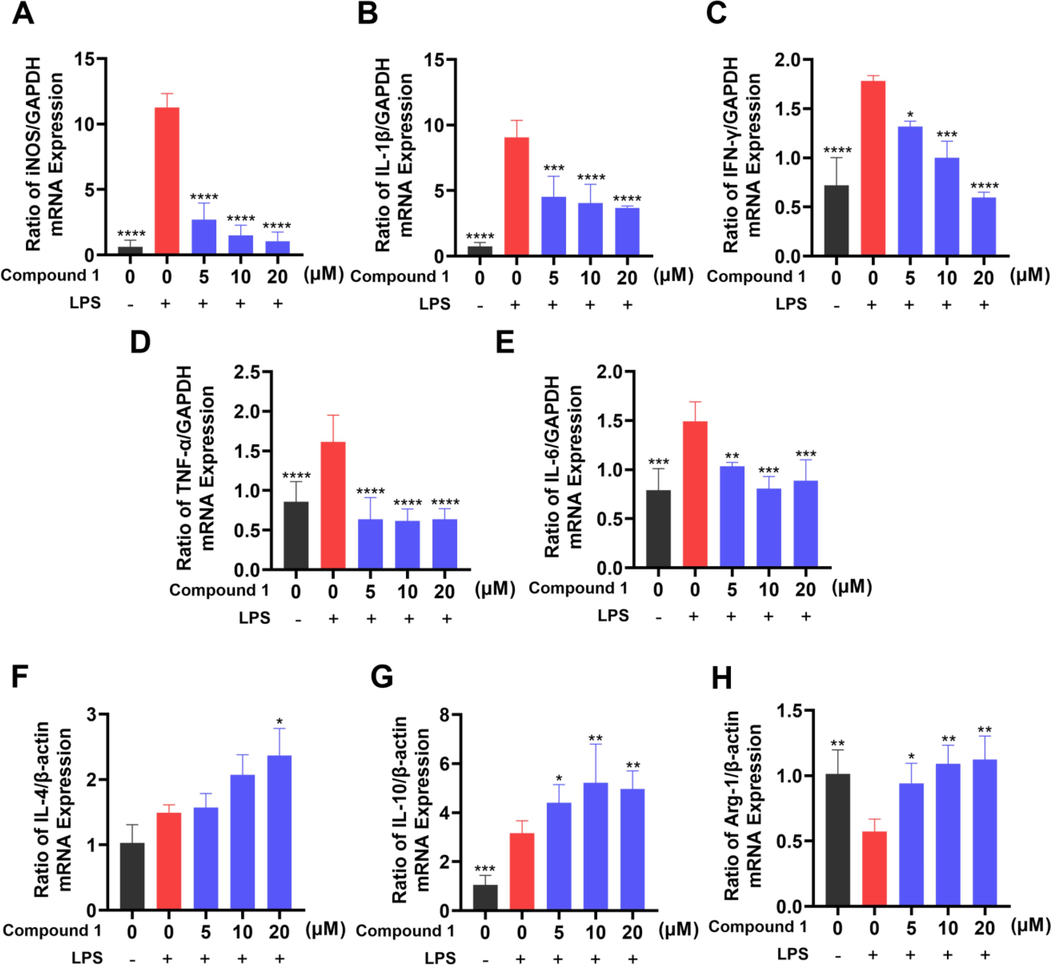

3.3 Effect of compound 1 on the mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines in LPS-exposed RAW 264.7 cells

In order to further validate the anti-inflammatory effect of compound 1, we investigated whether compound 1 regulated the mRNA expression levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines iNOS, IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10 and Arg-1 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 6A-H, compound 1 inhibited the LPS-stimulated mRNA expression of iNOS, IL-1β, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, while increased the mRNA expression of IL-4, IL-10 and Arg-1 in RAW 264.7 cells. These results showed that compound 1 exerted an inhibitory effect on the LPS-induced immune response.

Effects of compound 1 on LPS-induced iNOS (A), IL-1β (B), IFN-γ (C), TNF-α (D), IL-6 (E) IL-4 (F), IL-10 (G) and Arg-1 (H) mRNA level alteration in RAW 264.7 cells. mRNA levels were normalized to GADPH or β-actin mRNA and expressed as fold change relative to the control group. The data presented are the means ± SD of three independent experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, compared with the LPS group.

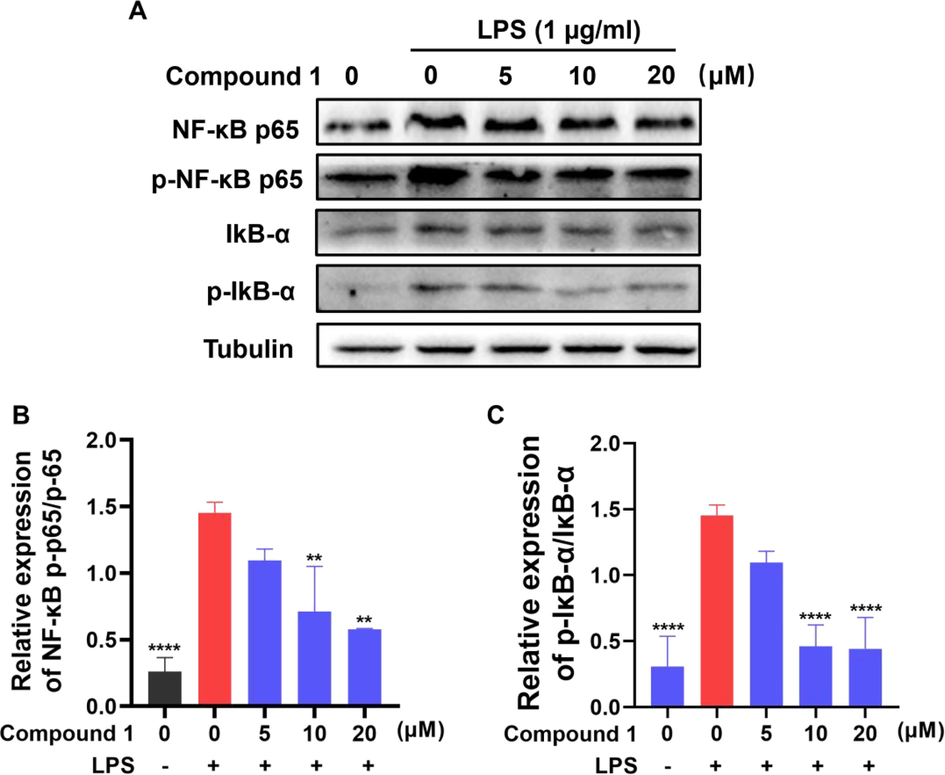

3.4 Compound 1 significantly inhibited NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells

Since the activation of NF-κB is the central event leading to the inflammatory process, targeting it represents an attractive approach for anti-inflammatory therapies. Phosphorylated IκBs are polyubiquitinated and afterwards degraded by the proteasome, thereby permitting NF-κBs to translocate to the nucleus and to exert their function (Bollrath et al., 2009). The phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 promotes its own nuclear translocation, which is an important marker of NF-κB pathway activation (Liu et al., 2017).

To clarify whether the inhibitory effect of compound 1 on inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells correlated with the NF-κB signaling pathway, the effects of compound 1 on LPS-triggered phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα were investigated using Western blotting. Compound 1 significantly restrained NF-κB p65 and IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 7A-C), indicating that compound 1 demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect by impeding the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

(A-C) Effects of compound 1 on LPS-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway related proteins expression in RAW 264.7 cells. The protein expression levels were determined using specific antibodies for IκB-α, p-IκB-α, NF-κB p65, NF-κB p-p65 and β-tubulin. The data presented are the means ± SD of three independent experiments; **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, compared with the LPS group.

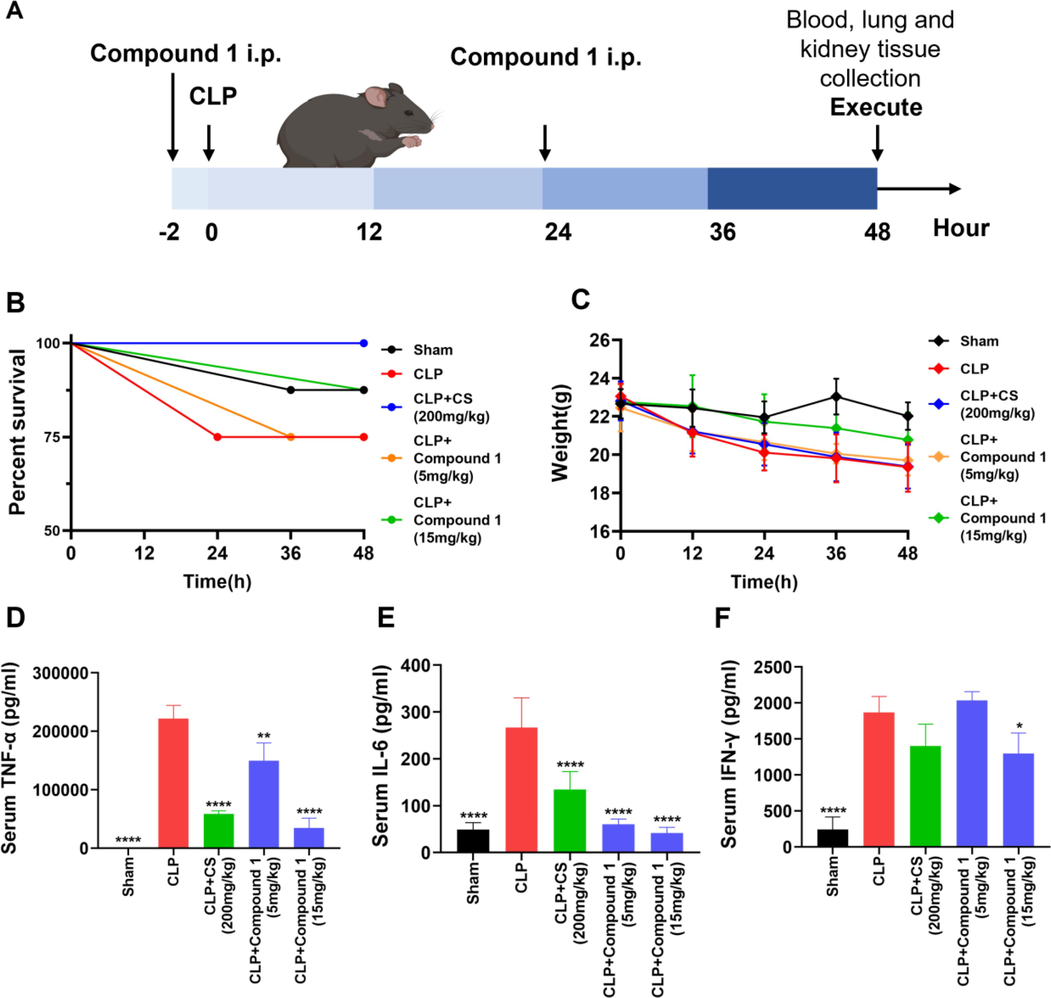

3.5 Compound 1 attenuated CLP-induced sepsis in mice

Sepsis, severe infections and the unbalanced immune response deleteriously affects physiological homeostasis of vital organ and often evolves into multi-organ failure (Lelubre et al., 2018). Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) is a standard experimental model of sepsis (Dejager et al., 2011). In the CLP model, a large number of intestinal bacteria enter the abdominal cavity flowed by bacterial peritonitis, and then the bacteria enter the systemic circulation. The infection triggers the excessive generation of inflammatory factors, causing a systemic inflammatory response that eventually progresses to multiple organ failure and collapse of the host defense system.

To further investigate the therapeutic potential of compound 1 for sepsis, we assessed survival rates and body weight at 12, 24, 36, 48 h after CLP in mice relative to controls. After 24 h post-CLP induction, septic mice showed progressive symptoms including decreased respiratory rate, more and more laborious breathing and minimal response to auditory and tactile stimuli. The results showed that the survival rate of mice increased after compound 1 treatment. Compared with CLP group in which the survival rate was 75 % at 48 h, the survival rate of mice in high dose group was 87.5 % (Fig. 8B). Meanwhile, the results showed weight loss in the CLP group. However, both low and high doses of compound 1 as well as CS treatment alleviated this phenomenon (Fig. 8C), which suggested that CS and compound 1 intervention could keep weight of septic mice to a certain extent. The serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ levels were also measured through ELISA. Those pro-inflammatory cytokines were elevated in the mice of CLP group, while decreased after compound 1 treatment in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 8D-F). High-dose compound 1 (15 mg/kg) has a similar or better effect compared with the positive drug CS. These data indicated that compound 1 was a promising inhibitor against CLP-mediated inflammatory responses in mice models of sepsis.

Protective effect of compound 1 on CLP-mediated sepsis. (A) Schematic diagram of the process of animal experiment. (B) Compound 1 was administered (5 or 15 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injection), and the survival rate was continuously observed. (C) The weight change of mice after CLP or sham operation. (D-F) Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ were detected through ELISA at 48 h after CLP operation. Data presented are the means ± SD of three independent experiments; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, compared with the CLP group.

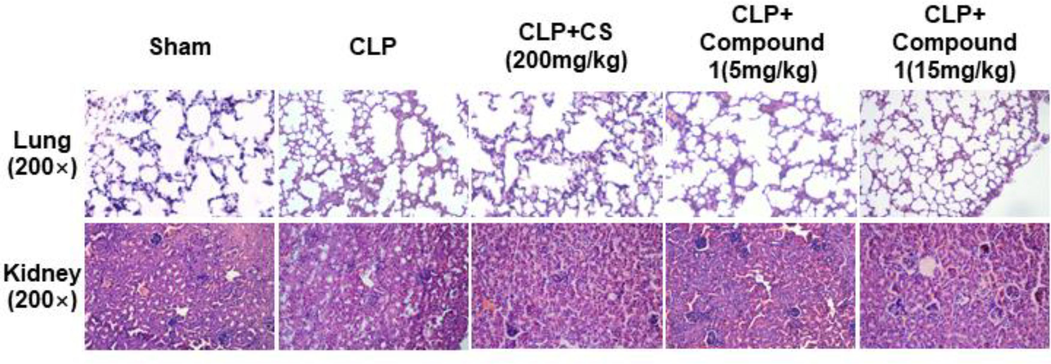

Furthermore, we conducted H&E staining to evaluate pathomorphological changes in lung and kidney tissues. As displayed in Fig. 9, we found that CLP enhanced inflammatory infiltration in lung and kidney tissues, induced morphological changes in renal tubules, which was alleviated in compound 1 and CS groups. In CLP group, the lung tissue of mice showed thickened diaphragm, infiltration of inflammatory cells and edema. As shown in the treatment group, the structure of lung tissue was more clear, and there were fewer edema bands or inflammation (Fig. 9). Renal tubular epithelial cell edema, vacuolar degeneration, brush border disappearance and renal tubular lumen dilatation were observed in the renal tissue of CLP group mice, and compound 1 treatment could significantly attenuated the pathological damage of renal tissue in sepsis model (Fig. 9). Taken together, treatment with compound 1 increased survival and alleviated tissue injury in septic mice, implying that compound 1 exhibited a potent anti-inflammatory effect in model mice with CLP-induced sepsis.

Effect of compound 1 on CLP-mediated organ injury in mice. Lung and kidney histopathology at post-operation 48 h from five groups; magnification: 200 ×.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, two undescribed (1 and 2) and eleven known compounds (3–13) were isolated and elucidated from C. bungei and C. inerme. Among them, compound 1 exhibited the strongest in vitro NO inhibitory activity. Further research showed compound 1 regulated the mRNA levels of various inflammatory cytokines by suppressing the NF-κB pathway in RAW 264.7 cells. Moreover, compound 1 exhibited the general anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing the levels of inflammatory cytokines and tissue injury in mice model of CLP-induced sepsis. We therefore concluded that compound 1 has a superior anti-inflammatory property during CLP-induced sepsis and could serve as a specific drug candidate for the prevention of bacterial sepsis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82072660) and the 111 Project (Grant No. B20016).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ba Vinh, L., Thi Minh Nguyet, N., Young Yang, S., Hoon Kim, J., Thi Vien, L., Thi Thanh Huong, P., Van Thanh, N., Xuan Cuong, N., Hoai Nam, N., Van Minh, C., Hwang, I., Ho Kim, Y., 2018. A new rearranged abietane diterpene from Clerodendrum inerme with antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 2001–2007.

- IKK/NF-kappaB and STAT3 pathways: central signalling hubs in inflammation-mediated tumour promotion and metastasis. EMBO Rep.. 2009;10:1314-1319.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Yang, F., Ao, H., Pan, Y., Li, HX., Sa, X.H., Tang, X., L,i K.L., Chen, X., Zhao, W.J., Tan, Y.Z., 2017. Chemical constituents of Ajuga ovalifolia var. calantha. Chin. Tradit. Herbal Drugs, 48, 3475–3479.

- Anti-inflammatory polyoxygenated cyclohexene derivatives from Uvaria macclurei. Phytochemistry. 2023;214:113797

- [Google Scholar]

- Compilatory Group of Compilation of Chinese Herbal Medicine, 1996. Compilation of Chinese herbal medicine People’s Health Press, Beijing, p353–354; 730–731.

- Rearranged abietane diterpenoids from the root of two Teucrium species. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:1697-1701.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cecal ligation and puncture: the gold standard model for polymicrobial sepsis? Trends Microbiol.. 2011;194:198-208.

- [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Committee of the Flora of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1982. Flora of China, 65(1). Science Press, Beijing, p. 150.

- Rearranged abietane diterpenoids from Clerodendrum mandarinorum. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res.. 2000;2:237-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatoprotective activity of Clerodendrum inerme against CCl4 induced hepatic injury in rats. Fitoterapia. 2008;79:24-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- New abietane diterpenoids from the mangrove Avicennia marina. Planta Med.. 2008;74:432-437.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathogenesis of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2019;20:5376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Megastigmane and iridoid glucosides from Clerodendrum inerme. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:333-336.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-complement activity of isolated compounds from the roots of Clerodendrum bungei Steud. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24:1720-1723.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biologically active diterpenoids in the Clerodendrum genus-a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2022;23:11001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms and treatment of organ failure in sepsis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.. 2018;14:417-427.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abietane diterpenoids from Clerodendrum trichotomum and correction of NMR data of Villosin C and B. Nat. Prod. Commun.. 2014;9:907-910.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diterpenoids and phenylethanoid glycosides from the roots of Clerodendrum bungei and their inhibitory effects against angiotensin converting enzyme and α-glucosidase. Phytochemistry. 2014;103:196-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: mechanisms, diagnosis and current treatment options. Military Med. Res.. 2022;9:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents from Clerodendrum bungei and their cytotoxic activities. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2009;92:1070-1079.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meroterpene-like compounds derived from β-caryophyllene as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem.. 2018;16:9454-9460.

- [Google Scholar]

- 4α-methyl-24β-ethyl-5α- cholesta-14, 25-dien-3β-ol and 24β-ethylcholesta-5, 9(11), 22E-trien-3β-ol, sterols from Clerodendrum inerme. Phytochemistry. 2003;63:415-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel lupene-type triterpenic glucoside from the leaves of Clerodendrum inerme. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2010;24:167-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete assignments of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of five rearranged abietane diterpenoids. Magn. Reson. Chem.. 2002;40:752-754.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2016;315:801-810.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioassay-guided isolation and mechanistic action of anti-inflammatory agents from Clerodendrum inerme leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2015;165:94-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abietane diterpenes from Clerodendron cyrtophyllum. Chem. Pharm. Bull.. 1993;41:1415-1417.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rearranged abietane diterpenes from Teucrium divaricatum subsp. villosum. Phytochemistry. 1994;37:1371-1375.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditional uses and pharmacological properties of Clerodendrum phytochemicals. J. Tradit. Complement. Med.. 2017;8:24-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rearranged abietane diterpenoids from the roots of Clerodendrum trichotomum and their cytotoxicities against human tumor cells. Phytochemistry. 2013;89:89-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diterpenoids from premna integrifolia. Phytochemistry Lett.. 2010;3:143-147.

- Meroterpene-like α-glucosidase inhibitors based on biomimetic reactions starting from β-caryophyllene. Molecules. 2020;25:260.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105338.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 2

Supplementary data 2