Translate this page into:

Efficient methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene over functionalized ZSM-5 supported cobalt complex catalysts

⁎Corresponding authors. fxjin@licp.cas.cn (Fuxiang Jin), hlliu@licp.cas.cn (Hailong liu), wangxicun@nwnu.edu.cn (Xicun Wang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

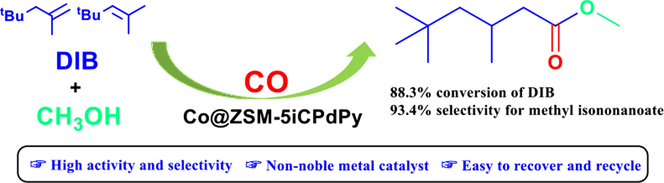

Nitrogen-containing functionalized ZSM-5-supported cobalt catalysts were prepared and applied to the methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene. Functionalize ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 exhibits excellent catalytic activity. Ideal conversion of diisobutylene (88.3%) and excellent selectivity for methyl isononanoate (93.4%) were obtained under mild conditions. The catalyst can be simply separated and reused with little change in structure or catalytic activity after 5 times.

Abstract

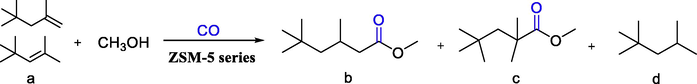

By grafting nitrogen-containing complexes onto ZSM-5 mesoporous material and then supporting a cobalt catalyst in situ, the methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene (DIB) was achieved. Moreover, a series of functionalized ZSM-5 mesoporous materials containing different nitrogen complexes were synthesized and characterized by FT-IR, N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, XRD, SEM, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Subsequently, the catalytic activity of functionalized ZSM-5 mesoporous materials and the reaction parameters in the methoxycarbonylation of DIB were investigated. The results revealed that the conversion of DIB was 88.3% and the selectivity for methyl isononanoate was 93.4% under solvent-free conditions at 6.0 MPa and 140 °C for 10 h by using the catalyst ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8. The potential mechanism for this catalytic reaction was also put forth. Admittedly, these inexpensive and easy-to-recover heterogeneous catalysts can replace the noble metal palladium complexes on a laboratory scale to achieve partial olefin carbonylation reactions.

Keywords

Molecular sieves

Functionalization

Cobalt complex

Diisobutylene

Methoxycarbonylation

1 Introduction

Carbonylation reactions constitute a powerful tool for the synthesis of carboxylic acids and their derivatives in the synthesis of large-scale industrial products (Kiss, 2001; Peng et al., 2019). Therein, hydroformylation and hydroesterylation of alkenes are also important components of alkenes carbonylation (Hebrard and Kalck, 2009; Dydio et al., 2014). On an industrial scale, cobalt- and rhodium-based homogeneous catalysts have been successfully used to date, although alternative metals continue to attract significant interest (Pospech et al., 2013). Traditionally, cobalt catalysts are often used to convert medium- and long-chain olefins into alcohols because of their high inherent hydrogenation activity. In addition, the rhodium-based catalyst system replaces the cobalt complex in the lower olefins carbonylation reaction due to its excellent catalytic activity and selectivity (Tudor and Ashley, 2007). Remarkably, the recovery costs of the metal and ligands are decisive regardless of which metal catalysts are used. Therefore, heterogeneous and immobilized homogeneous catalysts for carbonylation have been studied by many research groups, including mainly rhodium and cobalt catalysts (Rupflin et al., 2017; Li et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2015; Adint and Landis, 2014; Jakuttis et al., 2011; Li et al., 2018; Gorbunov et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2005). Additionally, researchers are becoming more and more interested in creating more affordable methods that enable the quantitative recovery of catalysts to accomplish catalyst circulation.

Isononanoic acid is a widely used chemical, suitable for the fine chemical production of surfactants, pharmaceutical intermediates and cosmetics, etc. At present, isononanoic acid is usually prepared from 2-ethyl hexanol through complex dehydration and hydrogenation. However, the disadvantages of this process are its low yield, large environmental pollution, equipment requirements, and corrosion problems, which limit its industrial application in large-scale production. In addition, the preparation of isononanoic acid from diisobutene by esterification and hydrolysis is a promising route, but the challenge is how to achieve high quality conversion of diisobutene methoxycarbonylation. To our knowledge, only a few homogeneous catalytic systems have been applied in hydroesterification of diisobutylene so far (Nobbs et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2018; Sang et al., 2018; Sang et al., 2020; Dühren et al., 2021). Based on the study of heterogeneous catalyst systems, only porous organic polymers (POLs) supported cobalt catalysts have been reported (Song et al., 2022).

To improve the efficiency of heterogeneous catalysts in carbonylation reactions, the molecular sieves provide ideal support for the immobilization of metal complexes due to their crystalline structure (Corma and Garcia, 2004). Their structures contain well-proportioned pores and channels so that only active ingredients with appropriate size and shape can be added; which can significantly improve the selectivity of carbonylation reactions. Furthermore, molecular sieves supported heterogeneous catalysts have made initial progress in the carbonylation of olefins (Silva et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2010; Maurya et al., 2011; Kuźniarska-Biernacka et al., 2013; Kuźniarska-Biernacka et al., 2012), and how to improve the catalytic activity and selectivity more effectively needs to be further investigated.

Herein, we performed the ZSM-5 molecular sieve, which had a relatively abundant Si—OH group to be grafted easier by silanization reagent and suitable micro-mesoporous structure. A series of functionalized molecular sieves supported by cobalt catalysts were synthesized, which have exhibited significant effects on the methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene through various schiff base complexes and amide complexes supported on molecular sieves. Subsequently, the surface properties of the catalysts were characterized by elemental analysis, infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), thermogravimetric (TG) and N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (BET). In addition, the effects of catalyst amount, reactant mole ratio, reaction time, reaction temperature, and pressure (CO) on the reaction were investigated.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

The commercial HZSM-5 (Si:Al = 500:1), which purchased from Jiangsu XFNAON Materials Technology Co., Ltd., were calcined in air at 550 °C for 4 h before use. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (99 wt%, Innochem), 3-Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (95 wt%, Innochem), 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde (98 wt%, Innochem), 4-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde (98 wt%, Innochem), 5-Hydroxypicolinaldehyde (98 wt%, Innochem), Imidazole (99 wt%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.), 2,2-Dipyridylamine (99 wt%, Innochem), Co2(CO)8 (98 wt%, Zhongze group), diisobutylene (2,4,4-trimethyl-1-pentene 79 wt%, 2,4,4-trimethyl-2-pentene 21 wt%, Innochem), carbon monoxide gas (99.999 wt%, Dalian Special Gases Co., Ltd), were used directly without further purification.

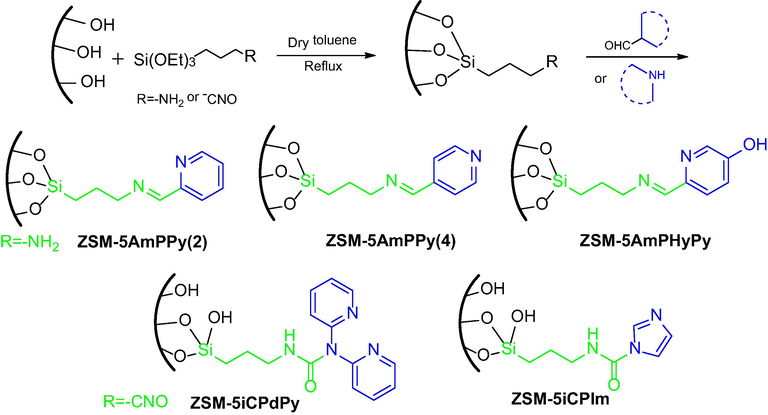

2.2 Catalysts supports preparation

As shown in Scheme 1, the catalyst support HZSM-5 with surface modification was pre-treated with the following procedure (Yang et al., 2010). Typically; the calcined HZSM-5 (10.0 g) was dispersed in anhydrous toluene (100 mL) to form suspension with vigorous stirring under dry nitrogen atmosphere. Afterwards, appropriate amount of 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (0.02 mol, 4.4 g) or 3-Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (0.02 mol, 5.0 g) was added dropwise to the solution, and refluxed at 110 °C for 24 h. Next, the processed solids were filtered, washed with anhydrous toluene for 3 times, and dried in vacuum at 60 °C overnight to obtained ZSM-5AmP (3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane) or ZSM-5iCP (3-Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane). Subsequently, dried ZSM-5AmP or ZSM-5iCP (5.0 g) was dispersed into the absolute ethanol (50 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere. Then, 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde (20 mmol, 2.1 g or 20 mmol other aldehyde) and triethylamine (20 mmol) were added dropwise under stirring, followed by refluxing at 80 °C for 24 h. Finally, the powder was filtered, washed three times with toluene-dichloromethane, and dried to obtain an off-white powdery solid (shown in Scheme 1). Moreover, the functionalized molecular sieves (ZSM-5iCPdPy, ZSM-5iCPIm) were synthesized using a similar method (Natour and Abu-Reziq, 2015).

Preparation method of surface modification of molecular sieves.

2.3 Catalysts characterization

The FT-IR spectrums with scanning range of 400–4000 cm−1 were obtained by Nicolet NEXUS 870 system (USA) using the anhydrous KBr wafer technique. The particle size and morphology of the samples were assessed by SEM images using Zeiss Sigma 300 (Germany) at 3 kV. TG/DSC analysis was carried out in N2 atmosphere from 50 to 800 °C using Netzsch STA449F3 simultaneous thermal analysis system (Selb, Germany). The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were recorded using a Micromeritics ASAP2010 instrument (USA) at liquid nitrogen temperature. Prior to the measurement, each sample was degassed for 4 h at 80 °C. XRD patterns were recorded using the Panalytical X’PERT PRO X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation at a scanning rate of 5° min−1 in the 2θ range of 5–60°. The XPS spectra were performed using an ESCALAB 250 X-ray photoelectron spectrometer with Al Kα X-rays as the excitation source. All binding energies were calibrated by C1s (284.6 eV) as the reference. The abreaction-corrected HAADF-STEM images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were recorded on equipment equipped with FEI-Talos F200s and FEI Super-X EDS Detector operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV.

2.4 Catalysts activity tests

The methoxycarbonylation reaction of diisobutylene with CO and methanol was carried out in a 100 mL stainless steel autoclave equipped with a stable temperature control and a mechanical stirrer. Typically, a certain proportion of pretreated HZSM-5 catalyst support, Co2(CO)8 precursor and methanol were added in the autoclave. After flushing with N2 for 3 times, the pre-fabrication of Co-based catalysts supported on pretreated HZSM-5 were conducted at room temperature for 30 min. Whereafter, a certain amount of diisobutylene was added to the autoclave. Subsequently, after the reactor was pressured with CO to 2.0 MPa, the reaction mixture was heated to the desired temperature and kept constant during the reaction. When the reaction was completed, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature, and the catalyst and product were separated by filtration. The products were analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) with an HP-5MS capillary column (Agilent 7890A/5975C). Using ethyl acetate as the internal standard, quantitative analysis of diisobutylene and products was performed by GC (Agilent 6820) with a SE-54 capillary column and a flame ionization detector (FID).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Catalysts characterization

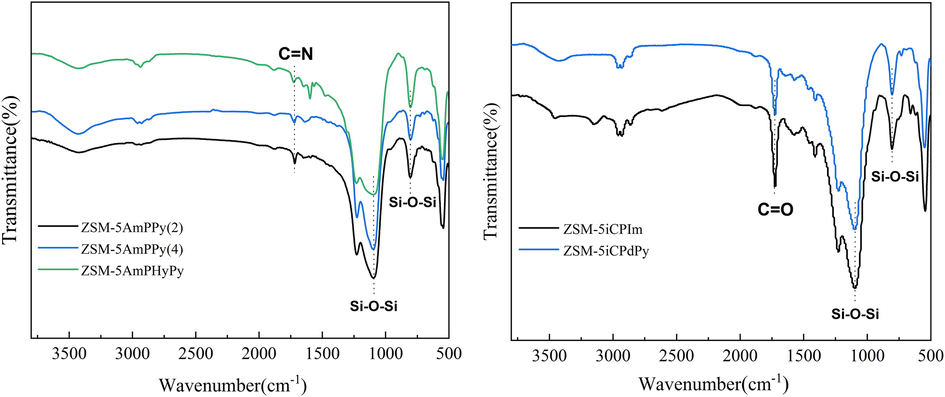

3.1.1 FT-IR analysis

The FT-IR spectra of the HZSM-5 catalyst supports pre-treated with different reagents were shown in Fig. 1. The FT-IR absorption peaks at 1088 and 802 cm−1 in all samples were attributed to the stretching vibration peak of the Si—O—Si bond in the ZSM-5 framework (Zhu et al., 2014). There was a wide absorption peak at 3400–3600 cm−1 attributed to the hydrogen bonds Si—OH absorption peak in the sample. The peaks at 449.1, 802.3, 1097.8, and 1227.8 cm−1 indicate the presence of the O—Si—O bond (Zhu et al., 2014). Furthermore, the presence of a C⚌N stretching vibration is demonstrated by the weak absorption peak at around 1635 cm−1 (October and Mapolie, 2017). The absorption at 2950 and 700 cm−1 is designated as the C—H stretching vibration and N—H bending vibration, respectively, and a new peak at 1707 cm−1 for the CO group indicates that the nitrogen-containing functional groups were successfully grafted onto ZSM-5 (Saikia et al., 2016).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectra of functionalized molecular sieves.

3.1.2 Elemental analysis

The amount of each functional group grafted onto the molecular sieves was determined by the nitrogen content obtained from the element analyzer, and the results were exhibited in Table 1. According to the calculation of nitrogen content, the grafting amount of nitrogen-containing functional groups in the HZSM-5 catalyst supports pre-treated with different reagents was 1.13,1.22,1.01,1.2 and 1.15 mmol/g respectively, which further indicated that the functionalized group was successfully grafted onto the molecular sieves.

Sample

N content

(wt.%)Functionalized group

amount (mmol/g)

ZSM-5AmPPy(2)

3.16

1.13

ZSM-5AmPPy(4)

3.41

1.22

ZSM-5AmPHyPy

2.82

1.01

ZSM-5iCPdPy

6.75

1.20

ZSM-5iCPIm

4.83

1.15

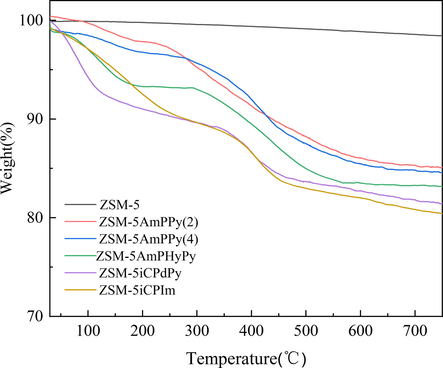

3.1.3 TG analysis

The thermal stability of functionalized molecular sieves was recorded by the TG method, and the weight losses were shown in Fig. 2. Before 100℃, the functionalized molecular sieve (ZSM-5AmPPy(2); ZSM-5AmPPy(4)) exhibited slight weight loss due to the release of adsorbed water and solvent. 12 % weight loss was observed at the temperature range of 230–450 °C, which attributed to the loss of grafted components and indicated that the organic components were successfully grafted onto ZSM-5 (Peña et al., 2001). A similar result was obtained for the functionalized molecular sieve (ZSM-5AmPHyPy; ZSM-5iCPdPy; ZSM-5iCPIm). The weight loss of about 8% at temperatures below 220 °C was attributed to the loss of solvent and unreacted silanol groups, while the loss of weight of the grafted organic components was observed at 320–450 °C (Jin et al., 2006). Therefore, the functionalized catalyst ZSM-5 can be operated stably at temperatures under 230 °C.

TG analysis curves of functionalized molecular sieves.

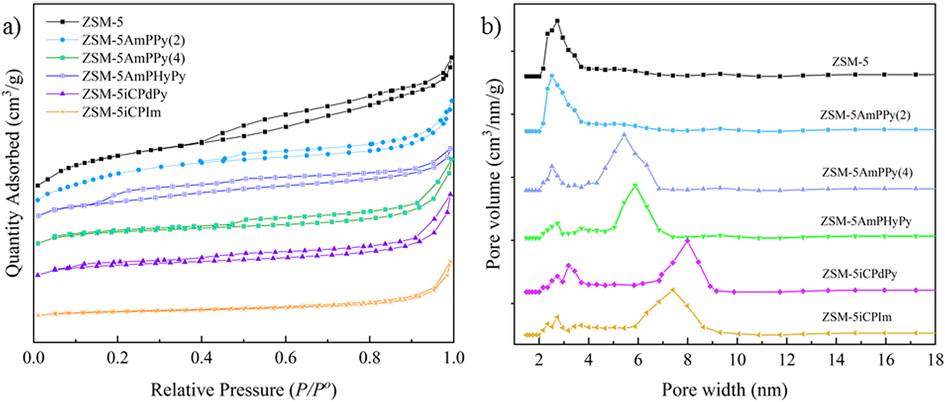

3.1.4 N2 adsorption–desorption

The BET isotherms and pore size distributions of functionalized molecular sieves were shown in Fig. 3(a-b). The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size parameters of the samples were listed in Table 2. The N2 adsorption–desorption of the samples presented the characteristics of both type Ⅰ and type Ⅳ isotherms, and the adsorption hysteresis phenomenon formed a hysteresis loop at the pressures of P/P0 = 0.4–0.95, indicating that the functionalized molecular sieves demonstrated regular pore channels and micro- and mesoporous properties. However, the pore volume and surface area of the sample are reduced because the hydroxyl group is replaced by a larger modifying group in the functionalized sample (Mitchell et al., 2011). The average pore diameter increased as a small fraction of the pores were blocked off after grafting (Song et al., 2018). Additionally, the fact that organic components were bound to the functionalized molecular sieves caused their hysteresis loops to slightly shrink.

(a)N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and (b) the corresponding BJH pore size distributions of functionalized molecular sieves.

Sample

BET surfacearea

(m2/g)Pore volume (cm3/g)

Average pore diameter (nm)

ZSM-5

407.8

0.23

2.23

ZSM-5AmPPy(2)

277.5

0.16

2.42

ZSM-5AmPPy(4)

268.9

0.13

5.34

ZSM-5AmPHyPy

220.8

0.11

5.72

ZSM-5iCPdPy

275.6

0.12

8.08

ZSM-5iCPIm

110.4

0.07

7.41

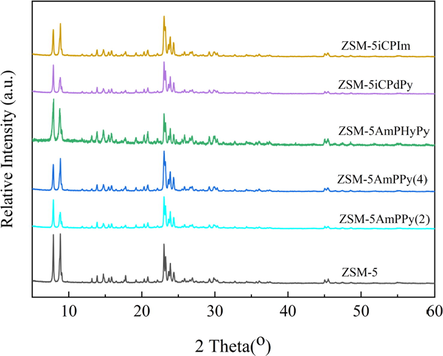

3.1.5 X-Ray diffraction (XRD) studies

The high-angle XRD spectrum of ZSM-5 and the functionalized molecular sieves were revealed in Fig. 4. Obviously, the functionalized molecular sieves catalyst exhibited the characteristic peaks of an MFI type zeolite (2θ = 7-9° and 23-25°) (Sun et al., 2016). It indicated that the framework of the functionalized molecular sieves was not damaged. However, the intensity of the diffraction peaks (ZSM-5AmPPy(2), ZSM-5AmPPy(4), ZSM-5AmPHyPy, ZSM-5iCPdPy, and ZSM-5iCPIm) was slightly reduced(2θ = 7-9°). It implies the crystallinity and orderliness of the functionalized molecular sieves decrease, which may be due to the reaction between Si-(OEt)3 of the grafting group and Si-OH on the molecular sieve skeleton to generate new Si-O-Si groups (Song et al., 2018; He et al., 2019).

XRD patterns of ZSM-5 and functionalized molecular sieves.

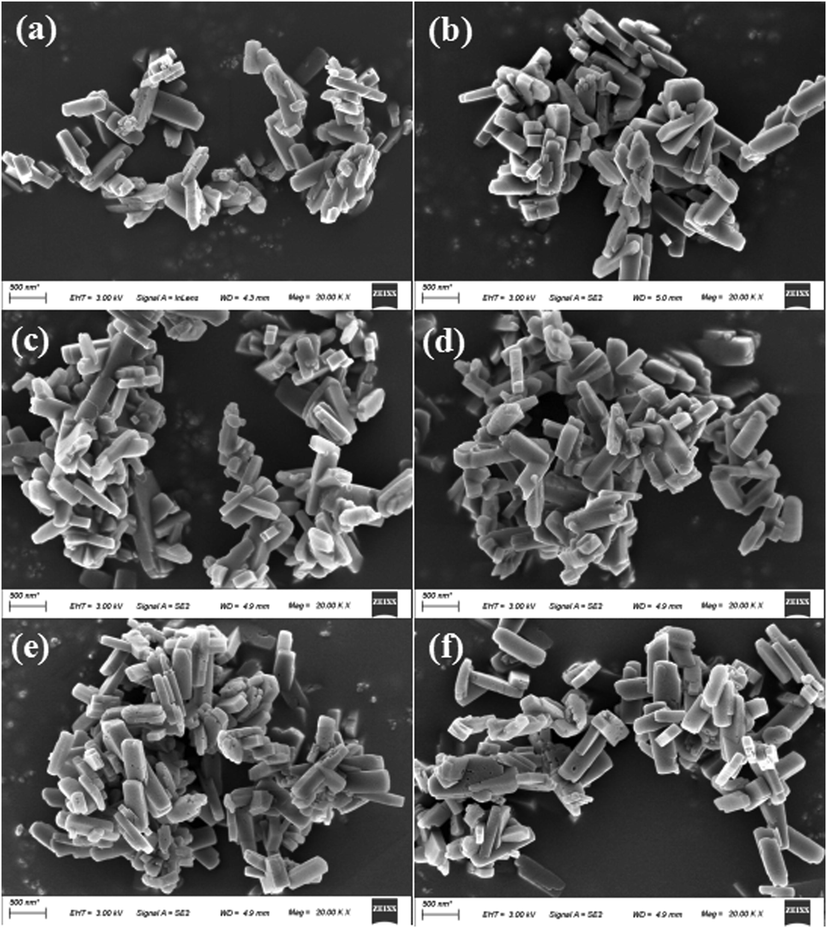

3.1.6 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies

As illustrated in Fig. 5, Fig (b-f) show the representative shapes of functionalized ZSM-5 zeolite nanocrystals. The nanocrystal particles were uniformly distributed with an average particle size of about 0.2 - 0.3 µm. In addition, functionalized ZSM-5 particles were slightly combined, which might be due to the combination of zeolite crystals. It indicates that the functionalization process will not affect the overall morphology of molecular sieve.

The SEM images of ZSM-5 and functionalized zeolite. (a) ZSM-5, (b) ZSM-5AmPPy(2), (c) ZSM-5AmPPy(4), (d) ZSM-5AmPHyPy, (e) ZSM-5iCPdPy, (f) ZSM-5iCPIm.

3.2 Performance of catalytic methoxycarbonylation

The catalytic performance of functionalized zeolite-supported cobalt catalysts was implemented through the typical hydroesterification of diisobutylene as the probe reaction (Table 3). Firstly, under heterogeneous conditions, the impact of functionalized molecular sieves with various nitrogen sources on the hydroesterification of diisobutylene was examined. It was found that the optimum yield could be obtained using ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 as the catalyst, with the conversion of DIB of 88.3%, the selectivity for methyl isononanoate of 93.4% (Table 3, entry 4). Moreover, when ZSM-5AmPPy(2)@Co2(CO)8 was used as the catalyst, higher conversion (85.9%) and selectivity (93.7%) could also be obtained, which may be due to the synergistic coordination between dinitrogen and cobalt in ZSM-5AmPPy(2)@Co2(CO)8. The yield of the obtained product decreased slightly under the catalysis of ZSM-5AmPHyPy@Co2(CO)8, which may be due to the weak acidity of the —OH group in ZSM-5AmPHyPy, resulting in a slight decrease in catalyst activity. Next, the impacts of various metal sources (Co, Ru, Rh) were investigated with medium conversion and favorable selectivity, except for CoCO3 due to poor solubility in the reaction system. In addition, the effects of various nitrogen-containing ligands on the hydroesterification of diisobutylene were investigated under homogeneous conditions. When pyridine or trihydroxypyridine were used as ligands, the conversion of diisobutylene was 90.5–85.1%, and the selectivity of methyl isononanoate was 86.5–82.5%. With 1,10-phenanthroline hydrate as a ligand, the conversion of diisobutylene was only 12.2% and the product selectivity was 86.6%, which may be due to the difference in basicity and coordination of each nitrogen ligand. Compared with the catalytic effect of the homogeneous system, the functionalized molecular sieve-supported cobalt catalyst exhibits better selectivity for methyl isononanoate, which may be due to the better coordination between cobalt and nitrogen and the appropriate pore structure of the modified molecular sieve. More intriguingly, the high diisobutylene conversion achieved by functionalized molecular sieve ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 may be related to the easier enhancement of the disproportionation reaction of Co2(CO)8 to [Co(CO)4]- in accordance with the proposed catalytic mechanism (Guo et al., 2020). Reaction conditions: Co2(CO)8 4 wt%, CH3OH:DIB = 15:1(mol ratio), CO 6.0 MPa, 140℃, 10 h.

Entry

catalyst

ligand

aN:M

(mol)Con.a/%

Sel. /%

b

c

d

1

ZSM-5AmPPy(2)@

Co2(CO)8

–

2

85.9

93.7

3.8

2.4

2

ZSM-5AmPPy(4)@

Co2(CO)8

–

2

84.3

91.1

4.7

3.6

3

ZSM-5AmPHyPy@Co2(CO)8

–

2

82.5

85.4

7.8

5.5

4

ZSM-5iCPdPy@

Co2(CO)8

–

4

88.3

93.4

3.6

2.9

5

ZSM-5iCPIm@

Co2(CO)8

–

3

76.6

91.5

4.5

3.8

6

ZSM-5iCPdPy@

CoCl2

–

4

50.7

86.8

7.6

4.2

7

ZSM-5iCPdPy@

CoCO3

–

4

21.2

85.5

6.9

5.9

8

ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co

(acac)2

–

4

56.3

78.4

11.2

9.4

9

ZSM-5iCPdPy@

Ru3(CO)12

–

4

60.2

82.0

9.6

7.9

10

ZSM-5iCPdPy@Rh

(CO)2(acac)–

4

57.0

90.1

5.4

4.5

11

Co2(CO)8

Pyridine

2

90.5

87.1

7.6

5.2

12

Co2(CO)8

Imidazole

4

74.4

82.1

8.1

8.5

13

Co2(CO)8

1,10-Phenanthroline

2

12.2

86.6

7.5

5.2

14

Co2(CO)8

3-Hydroxypyridine

2

85.1

86.1

7.6

4.9

The effects of various reaction factors were further investigated using ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 as the catalyst, and the results were summarized in Table 4. In accordance with the increase in the amount of cobalt, the conversion of diisobutylene increased from 71.2% to 95.2%. Additionally, selectivity for methyl isononanoate reached a maximum of 93.4% with 4 wt% Co2(CO)8 (Fig. S1). The effect of CH3OH/DIB was investigated. With an increase in CH3OH/DIB, the conversion of diisobutylene increased slightly from 89.2% to 91.4% (Fig. S2). When the total pressure of CO increased gradually, the conversion of diisobutylene increased to 90.1% and the selectivity for methyl isononanoate decreased slightly (Fig. S3). Moreover, when the temperature increased from 120℃ to 160℃, the conversion of diisobutylene increased from 72.4% to 92.1%, and the selectivity of methyl isononanoate was more than 90% (Fig. S4). Next, with the extension of the reaction time, the conversion rate of DIB gradually increased from 69.2% to 91.8% (Fig. S5), while the selectivity of methyl isononanoate essentially remained consistent. Reaction conditions: ZSM-5iCPdPy (0.16 g/ml) in reactants. DIB (0.02 mol), N:Co = 4:1(mol) in ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8.

Entry

Co2(CO)8 (wt%)

CH3OH /DIB

(mol)CO Press.

(MPa)Temp.

(℃)Time (h)

Con.a/%

Sel. /%

b

c

d

1

8

15

6.0

140

10

95.2

90.8

4.5

3.9

2

4

15

6.0

140

10

88.3

93.4

3.4

3.1

3

2

15

6.0

140

10

71.2

90.2

5.1

4.2

4

4

10

6.0

140

10

89.2

88.1

6.4

5.3

5

4

20

6.0

140

10

91.4

91.5

5.2

3.3

6

4

15

4.0

140

10

84.8

92.7

3.5

3.1

7

4

15

8.0

140

10

90.1

91.5

4.1

3.8

8

4

15

6.0

120

10

72.4

95.6

2.3

1.8

9

4

15

6.0

160

10

92.1

90.1

5.6

3.9

10

4

15

6.0

140

8

69.2

92.8

3.8

3.1

11

4

15

6.0

140

12

90.3

92.3

3.5

3.7

12

4

15

6.0

140

16

91.8

91.8

3.7

4.1

The substrate scope and limitations of the catalyst were explored according to the optimal reaction conditions by using ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 (Table 5). Initially, we evaluated the carbonylation of DIB with different alcohol sources. It was found that the conversion of DIB and selectivity were both reduced, which may be due to the steric hindrance of alcohol. With 1-hexene as the substrate, the selectivity for the corresponding methoxycarbonylation product was 75.4%. Then, hydroaminocarbonylation of DIB was further investigated. The conversion of DIB and selectivity were 44.2% and 71.6%, respectively.

Entry

Substrate

Con. of olefin (%)

Selectivity (%)

Linear-ester

Iso-ester

Iso-octane

1a

54.3

71.2

20.1

8.5

2a

40.8

43.8

44.7

11.5

3

14.2

68.2

24.3

7.3

4b

43.6

75.4

23.8

–

5c

44.2

71.6

21.4

6.8

3.3 Catalytic reaction mechanism

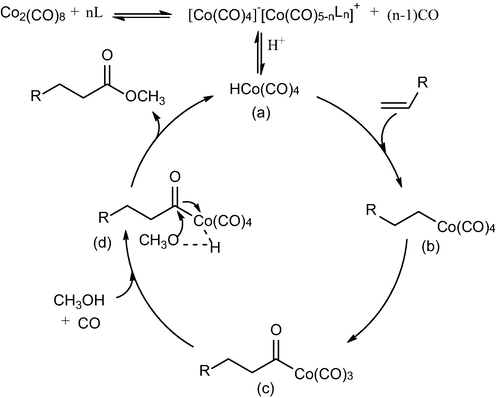

An explanation of the mechanism for methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene was proposed in a compact catalytic cycle (Tuba et al., 2003), as shown in Scheme 2. Firstly, nitrogen-containing complexes modified cobalt-catalyzed starts by the disproportionation of Co2(CO)8 to [Co(CO)4]-[Co(CO)5-nLn]+ followed by the formation of HCo(CO)4 (a) in protic solvent (Guo et al., 2020; Tuba et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2006; Gorbunov et al., 2019). HCo(CO)4 (a) reacts immediately with diisobutylene to produce compound (b), and the intramolecular migratory insertion of CO into the Co-C bond may result in the formation of the complex (c). The reactive species (c) undergoes a facile carbonylation in the presence of carbon monoxide to form the acyl complex (d), which affords an ester compound after treatment with methanol.

Proposed catalytic mechanism for methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene.

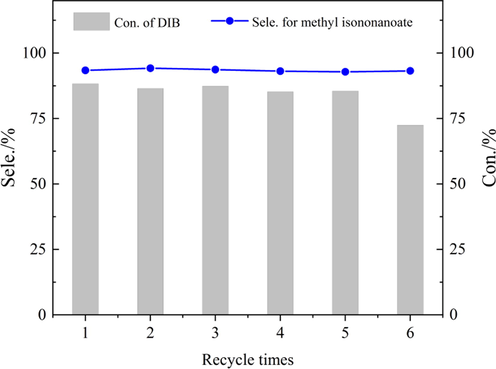

3.4 Recycling of the catalyst

In order to further evaluate the recyclability of the catalyst, a filter was utilized to extract the reaction liquid from the tube's bottom, separating the catalyst from the reaction mixture. The catalyst continues to remain at the bottom of the reactor for reuse without any treatment, which effectively prevents oxidation of the supported cobalt catalyst upon exposure to air. As shown in Fig. 6, after being reused five times, the conversion of DIB and selectivity of methyl isononanoate were not significantly decreased and stabilized at about 85% and 93%, respectively. In the sixth recycling, the conversion of DIB decreased slightly, and the selectivity remained basically stable. The cobalt content in the separated catalyst after the first reaction was 6.4% by ICP-OES analysis, while it was 5.7% after six cycles. The cobalt content in the reaction solution after the cycles was 8.3 ppm, indicating that there was a slight loss of cobalt on the catalyst during the reaction, which might be one of the reasons for the decreased catalyst activity. The infrared (Fig. S6) and BET (Fig. S7) characterizations before and after the catalyst recycling showed that the overall framework of the catalyst did not change significantly after six cycles, but the carbonyl peak was slightly reduced and the specific surface area of the catalyst decreased (Table S1), which might be due to the slight loss of supported cobalt carbonyl and local plugging of the ZSM-5 channels. EDS, XPS, (Fig. S8 a and b) and HAADF-STEM (Fig. S8 c) analyses unequivocally confirmed the presence of cobalt species and uniformly dispersed nitrogen species on the surface of functionalized ZSM-5 after the methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene, indicating that the chemical state of Co species remained at Co(Ⅱ) (Biesinger et al., 2011); which may be caused by partial oxidation of Co during the cycle.

Reusability of in the ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8 for DIB methoxycarbonylation. Reaction conditions: N:Co = 4:1(mol), Co2(CO)8 4 wt% (Not added during the cycle), CH3OH:DIB = 15:1(mol), 6.0 MPa CO, 140℃, 10 h.

3.5 Hot filtration experiment

In order to understand the heterogeneous nature of the supported catalyst, a thermal filtration experiment was performed over ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8. The results showed that after 4 h of processing, the conversion of diisobutylene was 36% and the selectivity of methyl isononanoate was 94%. After removing the catalyst from the reaction solution and continuing the reaction for 12 h (Fig. S9), the conversion rate of diisobutylene and the product selectivity were not obviously changed, which demonstrated the heterogeneity of the catalyst and that the homogeneous catalyst had no significant contribution.

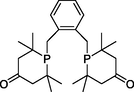

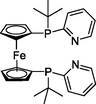

Some of the most active catalysts with different reaction conditions in the literature were compared, and the data was summarized in Table 6. Among these catalysts, the noble metal palladium was used as a homogeneous catalyst, demonstrating good selectivity and TOF values (240–480 h−1). Using formic acid (Table 6, entry 3) and paraformaldehyde (Table 6, entry 4) as the carbonyl sources, the reaction TOF value was only 4.7–1.7 h−1. Importantly, there were still problems with the circulation of palladium in a homogeneous catalytic system. According to the findings of this work, there are obvious advantages over the reported heterogeneous cobalt catalysts. L-1:

Entry

Catalyst

Ligand

CO/MPa

Temp./°C

Time/h

Sel./%

TOF/h−1

Refs

1a

Pd(OAc)2

L-1

5.0

105

4

99

240

(Nobbs et al., 2017)

2a

Pd(acac)2

L-2

4.0

120

20

99

480

(Dong et al., 2018)

3a

Pd(OAc)2

L-3

100

20

99

4.7

(Sang et al., 2018)

4a

Pd(OAc)2

L-4

120

55

90

1.7

(Sang et al., 2020)

5

Co@POLs

8.0

150

12

92.2

0.8

(Song et al., 2022)

6

ZSM-5iCPdy@Co2(CO)8

6.0

140

10

93.4

4.5

Present work

L-2:

L-2:

L-3:

L-3:

L-4:

L-4:

.

.

4 Conclusions

Functionalized ZSM-5 mesoporous materials were successfully synthesized by anchoring nitrogen-containing complexes and following in-situ supported cobalt catalyst, and the methoxycarbonylation of DIB was realized under solvate-free conditions. Under the optimum reaction conditions, high conversion of DIB (88.3%) and methyl isononanoate selectivity (93.4%) were achieved by functionalized molecular sieve ZSM-5iCPdPy@Co2(CO)8. In addition, the catalyst was also suitable for methoxycarbonylation of diisobutyl hydrocarbons with different alcohols and hydroaminocarbonylation of DIB. These findings provided a significant reference for replacing the noble metal palladium complexes and developing efficient and stable catalysts for methoxycarbonylation of olefins.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Immobilized bisdiazaphospholane catalysts for asymmetric hydroformylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:7943-7953.

- [Google Scholar]

- Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2011;257:2717-2730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydroformylation of 1-hexene over ultrafine cobalt nanoparticle catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A.. 2010;330:94-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supramolecular host-guest systems in molecular sieves prepared by ship-in-a-bottle synthesis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2004;6:1143-1164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cooperative catalytic methoxycarbonylation of alkenes: uncovering the role of palladium complexes with hemilabile ligands. Chem. Sci.. 2018;9:2510-2516.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenium-catalysed domino hydroformylation-hydrogenation-esterification of olefins, Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2021;11:5777-15578.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beyond classical reactivity patterns: Hydroformylation of vinyl and allyl arenes to valuable β- and γ-aldehyde intermediates using supramolecular catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:8418-8429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of nitrogenous bases as promoters of the reaction of ethylene carboalkoxylation on a cobalt catalyst. Russ. J. Appl. Chem.. 2019;92:1069-1076.

- [Google Scholar]

- New heterogeneous Rh-containing catalysts immobilized on a hybrid organic–inorganic surface for hydroformylation of unsaturated compounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter.. 2018;10:26566-26575.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of cobalt-catalyzed direct aminocarbonylation of unactivated alkyl electrophiles: Outer-sphere amine substitution to form amide bond. ACS Catal.. 2020;10:1520-1527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic oxidation of isoamyl alcohol on modified ZSM-5 molecular sieve catalysts prepared by different methods. React. Kinet. Mech. Cat.. 2019;128:1097-1109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cobalt-catalyzed hydroformylation of alkenes: Generation and recycling of the carbonyl species, and catalytic cycle. Chem. Rev.. 2009;109:4272-4282.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rhodium–phosphite SILP catalysis for the highly selective hydroformylation of mixed C4 feedstocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2011;50:4492-4495.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encapsulation of transition metal tetrahydro-Schiff base complexes in zeolite Y and their catalytic properties for the oxidation of cycloalkane. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2006;249:23-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encapsulation of manganese(III) complex in NaY nanoporosity for heterogeneous catalysis. Appl. Organometal. Chem.. 2012;26:44-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manganese complexes with triazenido ligands encapsulated in NaY zeolite as heterogeneous catalysts. Inorg. Chim. Acta.. 2013;394:591-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydroformylation of olefins by a rhodium single-atom catalyst with activity comparable to RhCl(PPh3)3. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2016;55:16054-16058.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single atom dispersed Rh-biphephos&PPh3@porous organic copolymers: highly efficient catalysts for continuous fixed-bed hydroformylation of propene. Green Chem.. 2016;18:2995-3005.

- [Google Scholar]

- A mini review on strategies for heterogenization of rhodium-based hydroformylation catalysts. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng.. 2018;12:113-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methoxycarbonylation of propylene oxide: A new way to β-hydroxybutyrate. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2006;250:232-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxidovanadium(IV) complexes of tetradentate ligands encapsulated in zeolite-Y as catalysts for the oxidation of styrene, cyclohexene and methyl phenyl sulfide. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2011;31:4846-4861.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of organic-functionalized mesoporous ZSM-5 zeolites by consecutive desilication and silanization. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2011;127:278-284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functionalized magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticle-supported palladium catalysts for CarbonylativeSonogashira coupling reactions of aryl iodides. ChemCatChem.. 2015;7:2230-2240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isomerizing methoxycarbonylation of alkenes to esters using a bis(phosphorinone)xylene palladium catalyst. Organometallics.. 2017;36:391-398.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of novel rhodium and ruthenium based iminopyridyl complexes and their application in 1-octene hydroformylation. J. Organomet. Chem.. 2017;840:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elucidating the local environment of Ti(IV) active sites in Ti-MCM-48: a comparison between silylated and calcined catalysts. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater.. 2001;44–45:345-346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alternative metals for homogeneous catalyzed hydroformylation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2013;52:2852-2872.

- [Google Scholar]

- Platinum group metal phosphides as heterogeneous catalysts for the gas-phase hydroformylation of small olefins. ACS Catal.. 2017;7:3584-3590.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functionalized montmorillonite supported rhodium complexes: Efficient catalysts for carbonylation of methanol. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2016;412:27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palladium-catalyzed selective generation of CO from formic acid for carbonylation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2018;140:5217-5223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palladium-catalyzed carbonylations of highly substituted olefins using CO-surrogates. Org. Chem. Front.. 2020;7:3681-3685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Styrene oxidation by manganese Schiff base complexes in zeolite structures. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2006;258:327-333.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient and reusable zeolite-immobilized acidic ionic liquids for the synthesis of polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers. Mol. Catal.. 2018;455:179-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methoxycarbonylation of diisobutylene into methyl isononanoate catalyzed by cobalt complexes supported with porous organic polymers. Mol. Catal.. 2022;527:112408

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient heterogeneous hydroformylation over Rh-metalated porous organic polymers: synergistic effect of high ligand concentration and flexible framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2015;137:5204-5209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparision of catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass to aromatic hydrocarbons over ZSM-5 and Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol.. 2016;121:342-346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of the pyridine-modified cobalt-catalyzed hydromethoxycarbonylation of 1,3-Butadiene. Organometallics.. 2003;22:1582-1584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of industrial hydroformylation processes by the adoption of rhodium-based catalyst: Part I. Platinum Met. Rev.. 2007;51:116-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced catalytic performances by surface silylation of Cu(II) Schiff base-containing SBA-15 in epoxidation of styrene with H2O2. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2010;256:3346-3351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydroformylation of 1-hexene for oxygenate fuels on supported cobalt catalysts. Catal. Today.. 2005;104:48-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic oxidation of styrene to benzaldehyde over a copper Schiff-base/SBA-15 catalyst. Chin. J. Catal.. 2014;35:1716-1726.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104907.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1