Translate this page into:

Exploring the mechanism and key active components of Gegen Qinlian decoction combined with XELOX in the treatment of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer based on network pharmacology and multi-omics analysis

⁎Corresponding author. lqyxm@hotmail.com (Qing Li)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

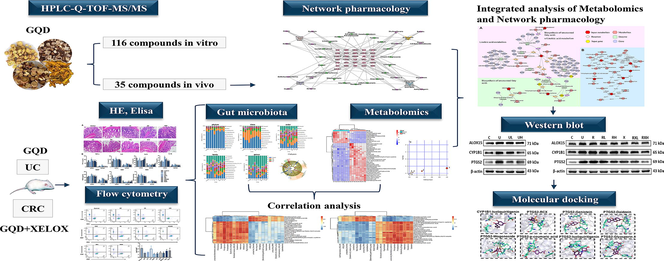

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune disease with a steady increase in global prevalence and long-term susceptibility to colorectal cancer (CRC). CRC is often treated with XELOX regimen (oxaliplatin and capecitabine), which is limited by the high toxicity, many adverse reactions and intolerance of patients, thus often leading to termination of chemotherapy. Traditional Chinese medicine is effective in improving patients' clinical symptoms. Gegen Qinlian decoction (GQD) is frequently utilized in the management of UC and has the potential to treat CRC. Whereas, there are few studies on GQD in the treatment of UC-associated CRC, and the therapeutic mechanism of GQD combined with XELOX has not been fully reported. Herein, HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS technique was used to analyze the main chemical components of GQD. Network pharmacology was performed to unveil the critical genes and components of GQD against UC and UC-associated CRC. The detection of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, VEGF, SOD, MDA and immune factors revealed that GQD played a key role in improving immune function, reducing inflammation and resisting oxidative stress. 16S rDNA sequencing technology results showed that GQD could maintain gastrointestinal homeostasis by increasing beneficial bacteria and decreasing harmful bacteria. Then, metabolomics based on HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS found that the combination of GQD and XELOX could significantly restore the disturbance of metabolites. Particularly, the compound-reaction-gene-enzyme network was first constructed to realize the combination of network pharmacology and metabolomics. The results showed that GQD may assist XELOX to play a synergistic anti-tumor role by regulating the key enzymes ALOX15, CYP1B1 and PTGS2 in unsaturated fatty acid metabolism. Finally, the mechanism was verified by western blot, and the key pharmacodynamic components were found by molecular docking. Overall, the current study offered fresh perspectives on both the prevention and treatment of UC to CRC as well as fresh concepts for the therapeutic application of GQD with XELOX to lessen the side effects of chemotherapy and enhance patients' quality of life.

Keywords

Ulcerative colitis

Colorectal cancer

XELOX

Gegen Qinlian decoction

Theraputic mechanism

1 Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune disease that mostly affects the mucosal layer of the colon and rectum (Loftus, 2005, Ordas et al., 2012). In recent years, UC is recognized as a disease that poses a threat to global health due to its recurrence (Zhu et al., 2019). Notably, prolonged UC is a risk factor of colorectal cancer (CRC) (Grivennikov, 2013, Rutter and Riddell, 2014). According to prior studies, individuals with UC had a 2.4 times higher risk of getting CRC compared to healthy population, and the risk for CRC in UC patients was around 30 % after 35 years (Eaden et al., 2001, Rogler, 2014). With a huge global prevalence (approximately 1.9 million new cases in 2020) and high mortality (0.9 million deaths in 2020), CRC is the second most common cancer in women and the third most prevalent cancer in men (Siegel et al., 2022). The transformation of UC into CRC may impose more heavy economic burden on families and society (Zhu et al., 2017). Therefore, a full understanding of the pathogenesis of UC-induced CRC is essential for the prevention and treatment of progression of disease as well as the optimization of existing treatments.

The combination therapy of oxaliplatin and capecitabine (also known as XELOX method) is one of the most commonly used chemotherapy regimens in the treatment of CRC (Shinji et al., 2022). However, XELOX therapy can produce multiple adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting, immune function decline, and dose involvement may cause serious neurotoxicity, thereby reducing patients' tolerance and compliance, and eventually leading to the termination of chemotherapy and affecting chemotherapy efficacy (Rodriguez et al., 2017, Quidde et al., 2018). Consequently, there remains an urgent need for exploring a new chemotherapeutic synergistic drug, reducing the dose of chemotherapy drugs or shortening the chemotherapy cycle on the premise of maintaining the chemotherapy effect, in order to enhance patients' quality of life and reduce toxicity and harmful effects brought by XELOX. In clinical practice, traditional Chinese medicine is frequently used in conjunction with chemotherapy medications because of its invaluable benefits for symptom relief, immune system regulation, and overall quality of life (Luo et al., 2019, Sun et al., 2021). As a traditional Chinese medicine, Gegen Qinlian decoction (GQD) contains the following ingredients: Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi (Gegen), Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Huangqin), Coptis chinensis French (Huanglian) and Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch (Gancao). The properties of GQD include anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antiviral, antibacterial, antioxidant, and intestinal mucosa protection (Liu et al., 2019, Cao et al., 2021, Li et al., 2021a, Li et al., 2021b). For thousands of years, this conventional medication has been extensively used to treat UC and diarrhea (Xu et al., 2021). In modern research, it has also been used to treat CRC with satisfactory results (Wang et al., 2021). However, although the therapeutic effect of GQD has been reported, its molecular mechanism of action and pharmacological are still not clearly understood. Moreover, the therapeutic effect and mechanism of GQD combined with XELOX therapy have rarely been elucidated.

Network pharmacology provides potent tools for exploring the action mechanism of conventional Chinese formulations (Shi et al., 2022). In order to identify the crucial genes and components that contribute to the pathogenesis of GQD against UC and UC-associated CRC, network pharmacology was performed in the current investigation. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, VEGF, SOD, MDA and immune factors detected by Elisa and flow cytometry revealed that GQD may treat UC and CRC by enhancing the immunomodulatory functions, anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor. As gastrointestinal diseases, UC and CRC can not only cause significant changes in the above indicators, but also cause disturbances in the structure of gut microbiota. Gut microbiota is a general term of microorganisms in the gut of organisms (Miyauchi et al., 2020, Zheng et al., 2020), which participate in the physiological processes such as immune and metabolic regulation and energy supply (Nishida et al., 2018). The structural imbalance of intestinal microflora often leads to numerous gastrointestinal diseases, so maintaining normal intestinal microflora is of great significance to body health (Khan et al., 2019). Accordingly, in the prevention and treatment of UC-associated CRC, altering gut microbiota and metabolites might be a promising therapeutic approach. 16S rDNA sequencing results revealed that widespread dysbiosis in the gut microbiota resulted from the development of UC to CRC, and inflammatory pathology was reduced by GQD through modifying the gut microbiota. After GQD intervention, the abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus was significantly increased, while the abundance of harmful bacteria such as Escherichia-Shigella was effectively inhibited, which confirmed the hypothesis that GQD could regulate body health by maintaining the homeostasis of intestinal microflora. Metabolomics studies evaluated changes in the metabolic pathway during the evolution of UC to CRC, the intervention of GQD combined with XELOX could enhance the rollback effect on differential metabolite concentrations. Spearman correlation analysis found that the changes of different bacteria genera were correlated with the improvement of metabolic indexes. This finding indicated that GQD improved the metabolic disorders such as unsaturated fatty acids by regulating intestinal microflora. Moreover, integrated analysis of metabolomics and network pharmacology predicted that GQD might assist XELOX in playing an anti-tumor role by regulating the metabolic pathway of unsaturated fatty acids through ALOX15, CYP1B1 and PTGS2, and the reliability of this hypothesis were then proved by western blot and molecular docking. Ononin, genistein, puerarin, daidzein, skullcapflavone II, baicalin, wogonoside, p-coumaric acid, coptisine, isoliquiritigenin and glyasperin A were the key active ingredients of GQD.

Taken together, network pharmacology, molecular pharmacology, high-throughput sequencing technology and metabolomics data were integrated in our study to fully confirm that GQD can prevent the transition from UC to CRC. The most important thing is that the action mechanism, pharmacodynamic effect and pharmacodynamic compositional basis of XELOX with GQD in the treatment of UC-associated CRC were systematically and deeply studied for the first time. Our current study not only paved the way for the prevention and treatment from UC to CRC, but also provided scientific basis for new clinical therapies to against CRC based on GQD.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and drug preparation

1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH), 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Distilled water was got from Wahaha Group Co. Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Ethanol, pentobarbital sodium and physiological saline were obtained from Yuwang Co. Ltd (Shandong, China). Methanol, formic acid and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Newd Jersey, USA). The ELISA kit (TNF-α, VEGF, IL-6, SOD, IL-10, MDA, IL-1β) was purchased from Shanghai MLBio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Oxaliplatin and capecitabine was obtained from Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Shandong, China). Protein for Western blot: ALOX15 (ab244205, Abcam), CYP1B1 (ab185954, Abcam), PTGS2 (ab179800, Abcam); Secondary antibody (bs-40295G-HRP; Biomass), rapid blocking solution (Genefist, Oxfordshire, UK).

According to the prescription ratio (8:3:3:2), Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi (Gegen), Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Huangqin), Coptis chinensis French (Huanglian) and Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch (Gancao) were immersed in 8 times amount of water for 30 min. First, Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi (Gegen) was boiled for 20 min. Next, the remaining medicine was boiled (40 min) for twice and filtered through a 200-mesh screen. Then, the two filtrates were combined and concentrated under pressure at 50 ℃. GQD was administered to rats at 2.16 g/kg (low dose, equivalent to half of the dose of GQD commonly used in clinical patients) and 8.64 g/kg (high dose, equivalent to the twice dosage of GQD commonly used in clinical patients).

2.2 Animals experiment

Six-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 86, males, weighing 180–220 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University. The animals were raised in a dedicated SPF standard room with a temperature of 22 ± 2 ℃, humidity of 40–60 %, and natural light and dark cycles from 7 am to 7 pm. All 86 rats were free to eat and drink for 7 days, and were deprived of water for 12 h before the experiment. The animal procedures were executed according to the SYPU Ethics Committee and carried out in line with the SYPU Guidelines for Animal Experimentation (SYPU-IACUC-S2022-07.28-201).

-

After 7 days of adaptive feeding, 6 rats were randomly selected to collect blank plasma in the EDTA tube (orbital blood collection). Then GQD was given intragastric administration (8.64 g /kg) once a day for 7 days. Plasma samples were collected (orbital blood collection) at 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h and 4 h after the last administration for subsequent analysis.

-

The remaining rats were randomly divided into 10 groups (n = 8): (1) control; (2) UC (after anesthesia with 30 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium, rats were given enema by injecting TNBS (100 mg/kg)-50 % ethanol mixture into the anuses of the rats); (3) UL (low-dose GQD to treat UC); (4) UH (high-dose GQD to treat UC); (5) CRC (Intraperitoneal injection of 30 mg/kg DMH once a week for 13 weeks, continued to induce cancer based on UC); (6) RL (low-dose GQD for the treatment of CRC); (7) RH (high-dose GQD for the treatment of CRC); (8) XELOX (4 mg/kg Oxaliplatin intraperitoneal injection once a week and 150 mg/kg capecitabine intragastric injection once a day for CRC rats); (9) RXL (low-dose GQD combined with XELOX for the treatment of CRC); (10) RXH (high-dose GQD combined with XELOX for the treatment of CRC).

After 12 h of fasting, rats were given TNBS (100 mg/kg)-50 % ethanol enema to induce UC, UL and UH rats were given GQD intragastric administration for 7 days, and daily weight was registered. On the 7th day after modeling, the disease activity index (DAI) score was recorded. For specific scoring criteria, please refer to Table S1.

After the last dose, orbital venous blood of each group was collected in coagulant tubes and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to collect serum samples. After the colon contents were collected, the colon was cleaned with physiological saline. Then, the colonic mucosal damage index (CMDI) was scored by observing the gross morphology of colon tissues. The scoring criteria and results were shown in Table S1. Part of colon tissues were clipped for Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, and the remaining were immediately frozen at −80 ℃.

Then, CRC, RL, RH, XELOX, RXL and RXH groups were given DMH (30 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection once a week for 13 weeks to continue to induce CRC. The rats in RL, RH, RXL and RXH groups were given GQD, while the rats in XELOX group were given the XELOX continuously for 6 weeks. Sample collection methods were the same as above.

2.3 HE staining

Colon tissues were fixed with paraformaldehyde (4 %). More than 24 h later, paraffin was adopted for embedding and section. After dewaxing, hydration and HE staining were carried out successively. Ultimately, the slices were observed under a 200-fold microscope and photographed.

2.4 Component identification experiment

-

Preparation of GQD for the analysis of vitro components: GQD was prepared according to the prescription ratio (8:3:3:2), and the filtrate was concentrated at 50 ℃ to the relative density of 1.05. A certain volume was taken and diluted with an appropriate amount of methanol, which was equivalent to 0.1 g crude drug per 1 mL. The liquid was filtered by 0.22 μm for instrumental use.

-

Preparation of plasma samples for the analysis of components in vivo: 1 mL plasma sample mixed with 3 mL methanol, then vortexed for 3 min and centrifugated at 12,000 rpm (5 min, 4 ℃). The supernatant was dry by placed under nitrogen flow and then added with 50 μL methanol, followed by vortexed for 3 min, ultrasound and centrifugated (5 min, 12,000 rpm, 4 ℃). After that, the supernatant was separated for instrumental analysis.

The chromatographic and mass spectrum conditions were shown in Table S2-3. Then, the chemical composition of GQD were analyzed and identified using PeakView 1.2.1 (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) software.

2.5 Network pharmacology analysis

The target of the components in plasma was predicted based on SwissTargetPrediction website (https://www.swisstargetprediction.ch). To obtain the key targets of components in plasma, SMILES strings of these components in vivo were entered into SwissTargetPrediction (https://www.swisstargetprediction.ch), from which possible targets for these compounds were returned based on predicted probability ranking order. Meanwhile, the genes of UC and CRC were obtained on Therapeutic Target Database (TTD, https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/) and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org), with “Ulcerative colitis” and “Colorectal cancer” as keywords. Venny (https://www.liuxiaoyuyuan.cn/) website was used to compare the differential genes of diseases and the targets of the components of GQD in plasma, and the intersection targets were selected. A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was draw through String database (https://cn.string-db.org/). Finally, the “herb-component-target” network was constructed by Cytoscape 3.10.0 (UC, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.6 Elisa assay

The expression levels of VEGF, SOD, TNF-α, IL-1β, MDA, IL-6 and IL-10 in colon and serum were quantitatively determined by ELISA kit according to the product description. First, 50 μL standard products in kit with different concentrations and 50 μL samples to be tested were added in each hole, and nothing is added to the blank hole. Next, each standard and sample holes were added with 100 μL of HRP labeled detection antibody and incubated in a 37 ℃ incubator for 60 min, and then washed with washing buffer for 3 times. 50 μL substrate A and 50 μL B were added to each hole. After incubation at 37 ℃ for 15 min, 50 μL termination solution was added to each hole successively. Finally, OD value of each hole was measured at 450 nm by enzyme-labeled instrument.

2.7 Flow cytometry detected of T lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+)

First, 0.5 mL blood was diluted to 3 mL and placed on 3 mL lymphocyte separation solution, and centrifuge at 400 g (20 min). The lymphocyte layer was cleaned with cleaning solution centrifuged for 10 min (250 g). Next, the precipitation was mixed with RBC lysate (3 mL) and incubated on ice (10 min), followed by terminated with PBS. The underlying cells were retained after centrifugation. PBS was used for suspending the cells, and then 0.5 μg FITC-CD3+, 0.25 μg APC-CD4+ and 0.25 μg PE-CD8+ were added and stained at 4 ℃ for 1 h away from light. 500 μL PBS was added and centrifuged 250 g for 10 min for cleaning. The underlying cells were re-suspended with PBS and transferred to the flow tube. Flow cytometry was adopted for detecting and calculating the proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes.

2.8 Intestinal microflora detection and data processing methods

DNA was extracted from every 0.1 g of frozen colon contents and genomic DNA integrity (including purity and concentration) was examined by 1 % agar-gel electrophoresis. The PCR amplification system was 20 μL, and the V3-V4 region was amplified using the universal primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Next, the products were identified, purified and quantified. Sequencing was then performed on the Illumina MiSeq PE250 system. Trimmomatic (v0.33) was used to filter the sequenced Raw Reads. And cutadapt 1.9.1 software was used to identify and remove primer sequences, then Clean Reads without primer sequences were obtained. After a series of preprocessing, the original data were obtained with high quality sequences, and then OUT clustering and species annotation were carried out. According to the annotation results, distribution histogram of the top 10 community in abundance at different levels were drawn by QIIME2 (https://qiime2.org/). In addition, linear discriminant analysis (LDA, https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/lefse/) was used to estimate the influence of microflora abundance on the difference effect. Finally, the significance analysis of inter-group differences (Metastats, https://metastats.cbcb.umd.edu/) was used to measure the differences in microflora abundance composition in disease group, control group and drug intervention groups, and to find biomarkers with statistical differences.

2.9 Metabolomics detection and data processing methods

1 mL of physiological saline and 100 mg of colon tissue were combined and homogenized for 3 min. Then, 500 μL of homogenate supernatant was measured and added with 10 μL internal standard solution (10 µg/mL of L-2-Chlorophenylalanine and heptadecanoic acid) and 1.5 mL methanol. The mixture was vortexed for 3 min before being centrifuged (12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C). The residue dried by nitrogen was then redissolved with 100 μL methanol, swirled for 3 min, ultrasonically for 3 min, then centrifuged (5 min, 12,000 rpm). The supernatant was collected for instrument analysis and detailed chromatographic and mass spectrum conditions were presented in the Table S4-5.

The original data was imported into XCMS (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu/) platform for peak identification, peak matching and other processing. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the processed data using SIMCA-P 14.0 (Umetrics, Malmo, Sweden), followed by orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and 200 permutation tests. Subsequently, a combination of multiple indicators was used to determine the differential metabolites. Subsequently, based on the precise mass/charge ratio and MS/MS information provided by HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS, the differential metabolites were identified using HMDB (https://hmdb.ca/), MetDNA (https://metdna.zhulab.cn/) and Mzcloud (https://www.mzcloud.org) databases. Then, MetaboAnalyst (https://www.metabo-analyst.ca/) platform was used for the analysis of KEGG pathway enrichment of differential metabolites. In addition, Spearman analysis between differential microflora and metabolites were conducted and visualized by heatmap. Finally, Metscape was used to obtain compound-reaction-enzyme-gene interaction networks to realize integrated analysis of network pharmacology and metabolomics.

2.10 Western blot analysis of crucial target proteins

Using the Pierce™BCA Protein Quantification Kit (Thermo, San Jose, CA, USA), the total proteins in the colon tissues were measured. Colon samples were diluted and added to 5 × protein loading buffer (Epizyme, Shanghai, China) to achieve a final protein concentration of 4 g/L (the volume ratio of samples to loading buffer was 4:1). For further examination, all samples were then denatured for 10 min (100 °C). After adding 2.5 μL of marker (Fisher, San Jose, CA, USA), 40 μg samples were added, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis from 60 V to 110 V were carried out. Then, the electric transfer was performed at 240 mA. Membranes were then blocked for 30 min using blocking solution (Genefist, Oxfordshire, UK), and then eluted for 3 times with TBST (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Next, the bands were incubated in ALOX15 (1:1000), CYP1B1 (1:5000), PTGS2 (1:1000) and β-actin (colon loading control, 1:1000) primary antibodies overnight at 4 ℃. Then, the protein bands were re-elution of TBST for 3 times, followed by incubated with 1:5000 secondary antibodies (bs-40295G-HRP; Biomass) away from light for 1 h. After coated with ECL developer solution evenly (US Everbright, Suzhou, China), the target bands were visualized by Tanon 5200 Multi fully automated chemiluminescence image analysis system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Finally, ImageJ (Rawak Software Inc., Stuttgart, Germany) software was utilized for the purpose of quantification.

2.11 Molecular docking

The protein files of ALOX15 (PDB: 2p0m), CYP1B1 (PDB: 3 pm0) and PTGS2 (5kir) were acquired from the RCSB PDB protein Crystal Structure database (https://www.pdbus.org/). PyMOL 2.4 (PyMOL software, Schrödinger, NewYork, NY, USA) was applied to remove water and ligands. AutoDock 4.2.6 (AutoDock software, Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for hydrogenation and charging. Mol2 structures of key pharmacodynamic ingredients were then obtained from TCMSP (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php), and the two receptors were semi-flexibly docked with the active ingredients by AutoDock 4.2.6 (AutoDock software, Scripps Research, La Jolla, CA, USA). In the end, PyMOL 2.4 (PyMOL software, Schrodinger, NY, USA) was used to visualize the molecular docking results.

2.12 Statistical analysis

All calculated experimental values were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted with Student’s t-test using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS software, SourceForge, San Diego, CA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Composition identification results of GQD in vitro and in vivo

Through analysis of the fragmentation pathways obtained from literature sources and public data, as well as database matching, comparison of mass accuracy, isotope patterns, and retention times of reference standards, 93 and 34 compounds in GQD were preliminarily identified in the positive and negative ion mode, respectively. And a total of 35 components in vivo were detected in GQD. The total ion chromatograms (TICs) were shown in Fig. S1. The specific information of each chemical component was shown in Table 1.

Components in vitro of GQD

No.

Identification

Formula

Found At Mass (m/z)

Ion adduction

Error/ppm

Rt (min)

Main product Ions (m/z, Da)

1

L-tryptophan

C11H12N2O2

205.0962

[M + H]+

−4.6

11.57

91.0546, 188.0697

2

Sucrose

C12H22O11

365.1046

[M+Na]+

−2.2

4.00

185.0406, 203.0513

3

Daidzein

C15H10O4

255.0649

[M + H]+

−1.1

39.22

91.0545, 137.0218, 199.0735, 227.0681, 237.0523

4

7,8,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone

C15H10O5

271.05972

[M + H]+

−1.4

45.89

169.0119, 253.0483

5

daidzein-4′-O-glucuronide

C21H18O10

431.09562

[M + H]+

−3.8

40.32

255.0538, 269.0766

6

Puerarin

C21H20O9

417.11726

[M + H]+

−1.8

25.70

267.0634, 297.0739, 351.0849, 381.0953, 399.1055

7

3′-Methoxypuerarin

C22H22O10

447.12684

[M + H]+

−3.9

26.45

411.1020, 429.1116

8

Mirificin

C26H28O13

549.15779

[M + H]+

−4.5

26.71

297.0735, 399.1048, 417.1150

9

Chrysin

C15H10O4

255.0649

[M + H]+

−1.1

39.22

137.0218, 153.0684

10

Norwogonin

C15H10O5

270.0528

[M + H]+

−1.0

36.93

123.0068, 169.0119, 253.0483

11

Baicalein

C15H10O5

271.0594

[M + H]+

−0.7

31.31

169.0119, 253.0483

12

2′,3,5,6′,7-Pentahydroxyflavone

C15H10O7

302.0427

[M + H]+

0.0

22.75

153.0158, 207.0275, 229.0476

13

quercetin

C15H10O7

303.0499

[M + H]+

0.0

22.75

229.0925, 257.0797

14

Baicalein II

C16H12O6

301.07003

[M + H]+

−2.1

45.87

286.0458, 301.0686

15

Dihydrooroxylin A

C16H14O5

287.0907

[M + H]+

−2.4

41.31

168.0044, 183.0280, 287.0895

16

Scutellaria flavonoids I

C17H14O6

315.0855

[M + H]+

−2.6

50.38

286.0784, 285.0748

17

5,7,2′,5′-Tetrahydroxy-8,6′-dimethoxyflavone

C17H14O8

347.07529

[M + H]+

−2.5

38.43

314.0404, 332.0511

18

Tenaxin I

C18H16O7

345.09596

[M + H]+

−2.7

49.97

315.0483, 330.0719

19

Skullcapflavone II

C19H18O8

375.10594

[M + H]+

−4.0

50.48

327.0474, 345.0571, 360.0815

20

Chrysin-7-O-glucuronide

C21H18O10

431.09562

[M + H]+

−3.8

40.32

255.0685, 308.9824

21

Baicalin

C21H18O11

447.09054

[M + H]+

−3.7

36.31

271.0583, 271.0379, 271.0594

22

Dihydrobaicalin

C21H20O11

449.10608

[M + H]+

−3.9

36.68

131.0481, 169.0119, 273.0734

23

Chrysin-8-C-glucoside

C21H20O9

417.11726

[M + H]+

−1.8

25.70

267.0740, 293.1011,307.0919

24

Wogonoside

C22H20O11

461.10572

[M + H]+

−4.6

41.54

285.0746, 270.0501, 285.0739

25

5,7,2′-trihydroxy-6-methoxyflavone 7-O-glucuronide

C22H20O12

477.10107

[M + H]+

−3.5

39.11

286.0485, 301.0688

26

Isoscutellarein8-O-D-glucuronate

C24H24O12

505.13272

[M + H]+

−2.6

35.35

127.0376, 137.0221, 257.0791

27

Tetracosane

C24H5O

310.0413

[M + H]+

−0.1

23.86

71.0188

28

Amoenin A

C27H34O14

583.19985

[M + H]+

−3.9

30.59

85.0281, 105.0697, 133.0634, 151.0365, 193.0488, 259.0946, 367.1162

29

Mullein glycoside

C29H36O15

625.21013

[M + H]+

−4.1

32.47

163.0374, 273.0742, 607.1372

30

Keratoside D

C31H40O15

653.24124

[M + H]+

−4.2

38.05

85.0304, 485.1510, 653.2460

31

P-hydroxybenzoic acid

C7H6O3

139.0387

[M + H]+

−2.0

14.54

56.9658, 65.0382, 80.0493

32

2,3-dihydrobenzofuran

C8H8O

121.06443

[M + H]+

−3.0

5.56

91.0557, 92.0242, 119.0349

33

2-methoxy-4-vinyl phenol

C9H10O2

151.07479

[M + H]+

−3.8

6.64

77.0400, 137.0430

34

5-hydroxycoumarin

C9H6O3

163.03883

[M + H]+

−0.9

19.14

51.0273, 135.0409, 163.0396

35

Transcaffeic acid

C9H8O4

181.04958

[M + H]+

0.2

38.77

153.0570, 181.0465

36

Ferulic acid

C10H10O4

195.06469

[M + H]+

−2.5

24.90

145.0367, 177.0530

37

Noroxyhydrastinine

C10H9NO3

192.06562

[M + H]+

0.5

31.41

134.0586, 149.0574

38

Cinnamic acid, 3,4-dimethoxy- (8CI)

C11H12O4

209.08102

[M + H]+

0.9

35.17

69.9853, 129.9953, 148.9615

39

Corydaldine

C11H13NO3

208.09661

[M + H]+

−1.0

30.96

77.0386, 91.0518, 105.0702

40

Moupinamide

C18H19NO4

314.13852

[M + H]+

−0.5

40.84

117.0325, 121.0640, 145.0275, 177.0518

41

Coptisine

C19H13NO4

320.09133

[M + H]+

−1.3

35.85

262.0833, 292.0926, 291.0888

42

Thalifendine

C19H15NO4

322.10664

[M + H]+

−2.3

32.89

251.0888, 279.0838, 307.0808

43

Groenlandicine

C19H15NO4

322.10664

[M + H]+

−2.3

32.89

279.0867, 307.0811

44

DeMethyleneberberine

C19H17NO4

324.12201

[M + H]+

−3.2

32.44

280.0948, 294.0736, 309.0963

45

Berberine

C20H17NO4

336.12194

[M + H]+

−3.2

39.68

278.0783, 292.0939, 306.0732, 320.0886

46

8-O-Berberine

C20H17NO5

352.11678

[M + H]+

−3.3

33.30

308.0901, 322.0695, 336.0844

47

Jatrorrizine

C20H19NO4

338.13732

[M + H]+

−4.0

35.66

294.1100, 308.0900, 322.1048

48

(R)-Canadine

C20H21NO4

340.15343

[M + H]+

−2.7

30.70

308.1263, 309.0980, 325.1284

49

Palmatine

C21H21NO4

352.15339

[M + H]+

−2.7

39.40

294.1087, 309.1295, 336.1092, 337.1239

50

Limonin

C26H30O8

471.20235

[M + H]+

2.1

19.85

274.1142, 471.1838

51

Acaciin

C28H32O14

593.18412

[M + H]+

−4.0

30.69

365.1005, 575.1720, 593.1236

52

p-coumaric acid

C9H8O3

165.05429

[M + H]+

−2.0

5.56

77.0393, 91.0537, 95.0498, 119.0476

53

Cis-Caffeic acid

C9H8O4

181.04958

[M + H]+

0.2

38.77

147.0654, 163.0591

54

Glyzaglabrin

C16H10O6

299.05517

[M + H]+

0.5

39.00

91.0540, 119.0511, 245.0380, 271.0580

55

HMO/isoformononetin

C16H12O4

269.08029

[M + H]+

−2.0

47.71

237.0524, 254.0555

56

Vestitol

C16H16O4

273.11186

[M + H]+

−1.0

19.85

137.0587, 149.0601

57

Glabranin

C20H20O4

325.14245

[M + H]+

−3.0

52.59

123.0455, 189.0912, 325.1167

58

Sigmoidin-B

C20H20O6

357.1332

[M + H]+

−0.2

51.01

127.0379, 147.0437, 175.0380, 357.1324

59

Vitexin

C21H20O10

433.11183

[M + H]+

−2.5

21.44

283.0586, 313.0686, 337.0691

60

Astragalin

C21H20O11

449.10608

[M + H]+

−3.9

36.68

273.0740, 274.0778, 449.1052, 450.1101

61

Gancaonin I

C21H22O5

355.15282

[M + H]+

−3.3

52.46

271.0479, 299.0538

62

Liquiritin

C21H22O9

419.13211

[M + H]+

−3.7

37.09

137.0226, 147.0431, 239.0680, 257.0790

63

Isoononin

C22H22O9

431.13225

[M + H]+

−3.3

35.65

256.0621, 269.0794

64

Isoschaftoside

C26H28O14

565.15327

[M + H]+

−3.4

29.40

447.1256, 565.1514, 566.1551

65

Kanzonol H

C26H32O5

425.23265

[M + H]+

0.9

55.69

351.1212, 369.1290, 425.1926

66

Liquiritigenin

C15H12O4

257.08015

[M + H]+

−2.7

31.98

91.0538, 119.0474, 137.0212

67

Isoliquiritigenin

C15H12O4

257.08015

[M + H]+

−2.7

31.98

137.0218

68

Naringenin

C15H12O5

273.07556

[M + H]+

−0.7

36.68

131.0477, 271.0497, 273.0755

69

Formononetin

C16H12O4

269.08029

[M + H]+

−2.0

47.71

197.0578, 237.0542, 254.0555

70

Medicarpin

C16H14O4

271.09577

[M + H]+

−2.6

49.25

123.0435, 137.0529, 271.0981

71

12-Methyltetradecanoate

C16H32O2

257.24735

[M + H]+

−0.6

61.07

69.0696, 81.0691

72

Odoratin

C17H14O6

315.0855

[M + H]+

−2.6

50.38

282.0493, 285.0366, 300.0589, 315.0821

73

Licoisoflavone B

C20H16O6

353.10112

[M + H]+

−2.4

53.82

283.0598, 299.0545

74

Licoisoflavone

C20H18O6

355.11731

[M + H]+

−0.9

52.15

121.0608, 149.0563, 353.1354

75

Corylifolinin

C20H20O4

325.14245

[M + H]+

−3.0

52.59

149.0578, 171.0780, 325.1408

76

Glycyrrhizol

C21H18O6

367.11636

[M + H]+

−3.4

53.19

283.0572, 311.0533, 309.0360, 339.1181

77

Isoliquiritin

C21H22O9

419.13211

[M + H]+

−3.7

37.09

239.0680, 257.0790

78

Ononin

C22H22O9

431.13225

[M + H]+

−3.3

35.65

256.0621, 269.0794, 270.0823

79

Glyasperins D

C22H26O5

371.18419

[M + H]+

−3

54.48

235.1320, 303.1208, 315.1212

80

8-Methoxyformononetin

C23H24O10

461.14303

[M + H]+

−2.6

29.86

253.0850, 281.0788, 299.0905

81

Glyasperin A

C25H26O6

423.17831

[M + H]+

−4.5

55.97

311.0534, 367.1150

82

Glabrol

C25H28O4

393.20453

[M + H]+

−3.8

55.21

205.0892, 321.1366

83

3-Hydroxyglabrol

C25H28O5

409.19911

[M + H]+

−4.5

56.13

353.1361, 409.1983

84

Schaeffertoside

C26H28O14

565.15327

[M + H]+

−3.4

29.40

397.0894, 415.0997, 433.1095

85

Glycyroside

C27H30O13

563.17391

[M + H]+

−3.6

31.69

413.1213, 431.1316, 563.1726

86

Vicenin-2

C27H30O15

595.16363

[M + H]+

−3.6

18.04

383.0697, 403.1316, 565.1693

87

Isoglycyrrhizinate and its isomers

C30H44O4

469.32961

[M + H]+

−3.5

45.69

405.3087, 433.3086, 451.3179

88

beta-Glycyrrhetinic acid

C30H46O4

471.34557

[M + H]+

−2.8

47.70

317.2114, 407.3257, 471.3422

89

Ursolic acid

C30H48O3

457.3662

[M + H]+

−3.1

48.02

123.1165, 375.1123, 457.2111

90

Glycyrrhizin

C42H62O16

823.40714

[M + H]+

−4.8

47.70

453.3319, 454.3382, 471.3436, 647.3734

91

Licorice-saponin G2

C42H62O17

839.40276

[M + H]+

−3.8

46.72

469.3271, 487.3378, 645.3599

92

(L)-alpha-Terpineol

C10H18O

155.14285

[M + H]+

−1.2

49.32

81.0764, 95.0848, 109.0981, 127.1112

93

Licochalcone B

C16H14O5

287.0907

[M + H]+

−2.4

41.31

168.0042, 183.0277

94

Chrysin

C15H10O4

253.04986

[M−H]-

−3.1

34.34

254.0520, 253.0492

95

Daidzein

C15H10O4

253.04986

[M−H]-

−3.1

34.34

91.0183, 133.0252, 209.0481, 224.0474

96

Genistein

C15H10O5

269.0452

[M−H]-

−1.3

47.26

195.0387, 225.0443

97

3′-methoxydaidzein

C16H12O5

283.06031

[M−H]-

−3.1

51.42

239.0337, 268.0369, 283.0611

98

puerol B

C18H16O5

311.09172

[M−H]-

−2.5

37.69

93.0344, 119.0503, 267.1033

99

Genistin

C21H20O10

431.09809

[M−H]-

−0.6

24.48

255.0666, 283.0610, 311.0560, 431.0991

100

Puerarin

C21H20O9

415.1027

[M−H]-

−1.8

27.61

267.0666, 295.0618, 308.0643

101

3′- Methoxy Puerarin

C22H22O10

445.11334

[M−H]-

−1.5

27.87

282.0518, 297.0763, 325.0706

102

Ononin

C22H22O9

429.11865

[M−H]-

−1.1

33.09

266.0581, 281.0816, 309.0768

103

Genistein-8-C-xylosyl-(1–6) -glucoside

C26H28O14

563.1401

[M−H]-

−0.9

30.66

283.0613, 311.0557, 563.1403

104

Baicalein

C15H10O5

269.0452

[M−H]-

−1.3

47.26

223.0416, 241.0522, 269.0447

105

Chrysin-7-O-glucuronide

C21H18O10

429.08142

[M−H]-

−3.0

42.53

209.0593, 252.2539, 253.0509

106

Baicalin

C21H18O11

445.07733

[M−H]-

−0.7

38.20

159.0326, 269.0450, 275.0253

107

Darendroside B

C21H32O12

475.18183

[M−H]-

−0.6

23.47

267.0665, 295.0617, 415.1032

108

Wogonoside

C22H20O11

459.09134

[M−H]-

−4.2

43.53

175.0244, 268.0485, 283.0598, 459.0946

109

Chrysin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside

C26H28O13

547.1453

[M−H]-

−0.8

27.99

267.0656, 295.0604, 547.1451

110

Chrysin 7-O-Beta-Gentiobioside

C27H30O14

577.15679

[M−H]-

0.9

21.04

294.0530, 429.1193, 457.1129

111

Martynoside

C31H40O15

651.229

[M−H]-

−0.7

38.88

475.1835, 605.2107

112

Protocatechuic acid

C7H6O4

153.0191

[M−H]-

−1.5

16.55

91.0200, 109.0301, 153.0200

113

3,4-Dimethoxycinnamic acid

C11H12O4

207.0660

[M−H]-

−1.4

30.75

149.0554, 192.0361

114

3-Carboxy-4-hydroxy-phenoxy glucoside

C13H16O9

315.07188

[M−H]-

−0.9

13.27

101.0288, 108.0221, 109.0305, 123.0441

115

Luteolin

C15H10O6

285.03954

[M−H]-

−3.2

46.53

151.0045, 175.0388, 199.0410, 267.0295

116

Rosmarinie acid

C18H16O8

359.07592

[M−H]-

−3.7

50.29

344.0530, 359.0763

117

Pinoresinol glucoside

C26H32O11

519.18673

[M−H]-

−0.9

33.21

151.0375, 309.0671

118

(+)-lariciresinol gluciside

C26H34O11

521.20243

[M−H]-

−0.8

30.78

299.1417, 329.1391

119

Malic acid

C4H6O5

133.01417

[M−H]-

−0.6

4.63

71.0287, 115.0033, 133.0121

120

Danshensu

C9H10O5

197.04533

[M−H]-

−1.1

12.29

123.0454, 135.0450, 179.0281, 179.040, 197.0502

121

Isoliquiritigenin

C15H12O4

255.06548

[M−H]-

−3.2

45.23

91.0216, 119.0514, 135.0102

122

Carthamidin

C16H12O6

299.05521

[M−H]-

−3.0

47.07

284.0325, 299.0554

123

Liquiritin

C21H22O9

417.11814

[M−H]-

−2.3

33.64

91.0203, 119.0506, 135.0088, 255.0657

124

Isoliquiritin

C21H22O9

417.11814

[M−H]-

−2.3

33.64

119.0505, 135.0088, 255.0665

125

Narcissoside

C28H32O16

623.16207

[M−H]-

0.5

24.33

415.1018, 416.1060, 623.1650

126

Glycyrrhizin

C42H62O16

821.39572

[M−H]-

−1.0

47.53

351.0554, 822.3965

127

Darendoside A

C19H28O11

431.15585

[M−H]-

−0.1

20.80

191.0572, 233.0653, 311.0557

Components in vivo of GQD

No.

Identification

Formula

Found At Mass (m/z)

Ion adduction

Error/ppm

Rt (min)

Main product Ions (m/z, Da)

1

Daidzein

C15H10O4

255.06507

[M + H]+

−0.5

39.86

91.0548, 137.0245, 199.0747, 227.0704, 237.0556

2

7,8,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone

C15H10O5

271.06021

[M + H]+

0.4

45.98

215.0764, 243.0605

3

Puerarin

C21H20O9

417.11698

[M + H]+

−2.5

26.11

267.0645, 297.0745, 351.0846, 381.0953, 399.1050

4

3′-Methoxypuerarin

C22H22O10

447.12707

[M + H]+

−3.4

26.71

297.0771, 411.1061, 429.1152

5

Mirificin

C26H28O13

549.15845

[M + H]+

−3.3

26.93

297.0758, 399.1067, 417.1177

6

Chrysin

C15H10O4

255.06507

[M + H]+

−0.5

39.86

152.0614, 227.0704

7

Dihydrooroxylin A

C16H14O5

287.09119

[M + H]+

−0.7

42.03

69.0743, 168.0046

8

Skullcapflavone II

C19H18O8

375.10734

[M + H]+

−0.3

50.73

227.0544, 327.0400, 345.0609

9

Baicalin

C21H18O11

447.09137

[M + H]+

−1.8

32.73

271.0596

10

Chrysin-8-C-glucoside

C21H20O9

417.11698

[M + H]+

−2.5

26.11

267.0645, 297.0745, 417.1166

11

Wogonoside

C22H20O11

461.10681

[M + H]+

−2.2

42.09

270.0516, 285.0752

12

Coptisine

C19H13NO4

320.09171

[M + H]+

−0.1

37.04

262.0860, 277.0731, 292.0963

13

Thalifendine

C19H15NO4

322.10701

[M + H]+

−1.2

33.29

250.0866, 279.0906

14

Groenlandicine

C19H15NO4

322.10701

[M + H]+

−1.2

33.29

207.0833

15

DeMethyleneberberine

C19H17NO4

324.12271

[M + H]+

−1.0

32.72

280.0961, 309.0979

16

Berberine

C20H17NO4

336.1227

[M + H]+

−1.0

41.49

292.0973, 306.0769, 320.0915

17

Jatrorrizine

C20H19NO4

338.13847

[M + H]+

−0.6

35.97

279.0884, 294.1113, 323.1140

18

Palmatine

C21H21NO4

352.15399

[M + H]+

−1.0

40.89

308.1276, 336.1225, 337.1306

19

p-coumaric acid

C9H8O3

165.05409

[M + H]+

−3.2

5.58

91.0545, 119.0495, 123.0440, 147.0399

20

Astragalin

C21H20O11

449.1061

[M + H]+

−3.9

34.51

273.0721, 449.1996

21

Isoononin

C22H22O9

431.13329

[M + H]+

−0.9

35.96

269.0805, 431.1117

22

Liquiritigenin

C15H12O4

257.08059

[M + H]+

−1.0

32.72

91.0568, 119.0498, 137.0228

23

Isoliquiritigenin

C15H12O4

257.08059

[M + H]+

−1.0

32.72

137.0228, 147.0413

24

Ononin

C22H22O9

431.13329

[M + H]+

−0.9

35.96

213.0971, 254.0557, 269.0805, 431.1117

25

Glyasperin A

C25H26O6

423.18008

[M + H]+

−0.3

58.82

327.2220, 367.2001

26

Glycyrrhizin

C42H62O16

823.40792

[M + H]+

−3.8

47.72

453.3350, 471.3325, 647.3756

27

Licorice-saponin G2

C42H62O17

839.40909

[M + H]+

3.7

47.32

839.4986

28

(L)-alpha-Terpineol

C10H18O

155.1427

[M + H]+

−1.2

49.64

156.7057, 157.0821

29

Licochalcone B

C16H14O5

287.0911

[M + H]+

−0.7

41.03

69.0743, 168.0046

30

Genistein

C15H10O5

269.0454

[M−H]-

−0.5

47.68

63.0251, 157.0377, 224.0498

31

3′-methoxydaidzein

C16H12O5

283.06096

[M−H]-

−0.8

51.48

239.0340, 268.0383, 283.0592

32

Puerarin

C21H20O9

415.10221

[M−H]-

−3.0

27.39

267.0651, 295.0590, 307.0558

33

3′- Methoxy Puerarin

C22H22O10

445.11259

[M−H]-

−3.2

27.71

297.0774, 325.0689, 430.0994

34

Baicalin

C21H18O11

445.07668

[M−H]-

−2.2

34.35

85.0298, 113.0247, 269.0440

35

Wogonoside

C22H20O11

459.09206

[M−H]-

−2.7

43.68

175.0256, 268.0366, 283.0605

36

Chrysin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside

C26H28O13

547.14423

[M−H]-

−2.7

27.82

277.0519, 295.0606, 325.0709

37

Chrysin 7-O-Beta-Gentiobioside

C27H30O14

577.15547

[M−H]-

−1.4

20.62

457.0922, 508.9563

38

Isoliquiritin

C21H22O9

417.11796

[M−H]-

−2.7

35.98

119.0520, 135.0450

39

Glycyrrhizin

C42H62O16

821.39558

[M−H]-

−1.1

47.64

351.0540, 822.4001

40

Baicalein

C15H10O5

269.0454

[M−H]-

−0.5

47.68

63.0251, 169.0649, 224.0498, 268.7776

3.2 Network pharmacology predictive analysis

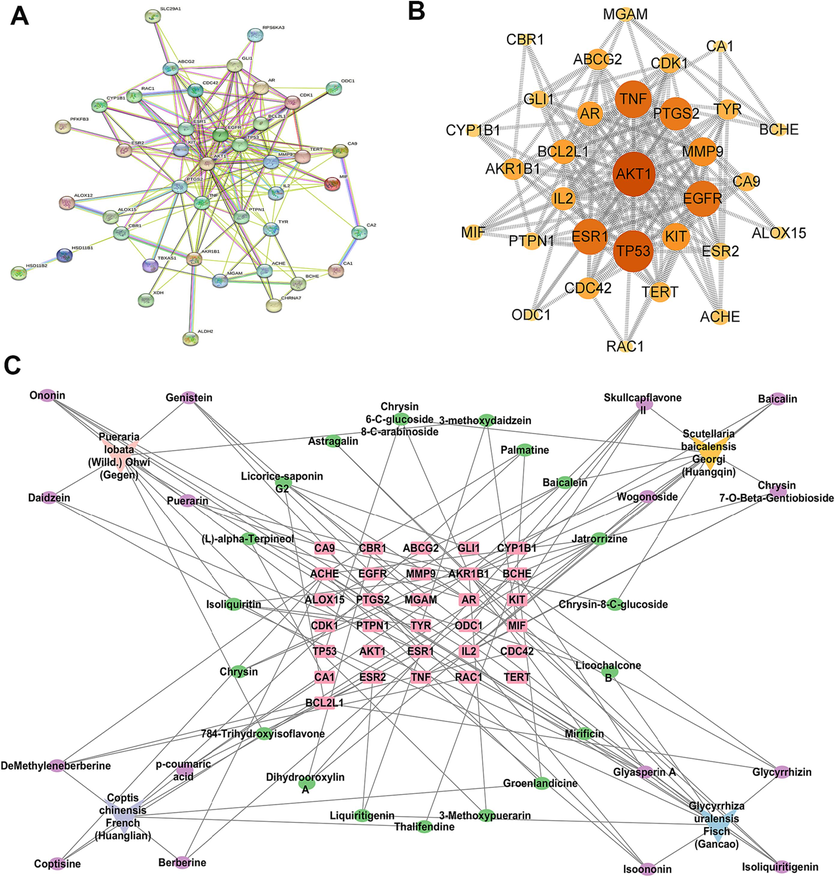

43 targets were obtained in total from the intersection of 35 in vivo component targets (the top 5 targets with the highest Probability value) and disease targets. Then, PPI network diagram of 43 targets was constructed through String database (Fig. 1A). With the degree value > 4 as the standard, 31 key targets were screened out and the interaction network diagram was drawn (Fig. 1B). The list of targets was shown in Table S6. Finally, using Cytoscape 3.9.1 (UC, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA) software, a network diagram of 4 herb, 35 components and 31 targets was constructed (Fig. 1C). The top 4 components with the highest degree of each herb were identified as the key active components that might play important roles in drug efficacy. As a result, Ononin, genistein, puerarin, daidzein were the key components in Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi (Gegen); Skullcapflavone II, chrysin 7-O-beta-gentiobioside, baicalin, wogonoside were the key components in Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Huangqin); DeMethyleneberberine, p-coumaric acid, coptisine, berberine were the key components in Coptis chinensis French (Huanglian); Isoliquiritigenin, glyasperin A, isoononin and glycyrrhizin were the key components in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch (Gancao).

Prediction results of network pharmacology study. PPI diagram network (A); Network diagram of 31 key targets (B); “Herb-component-target” multivariate network (C).

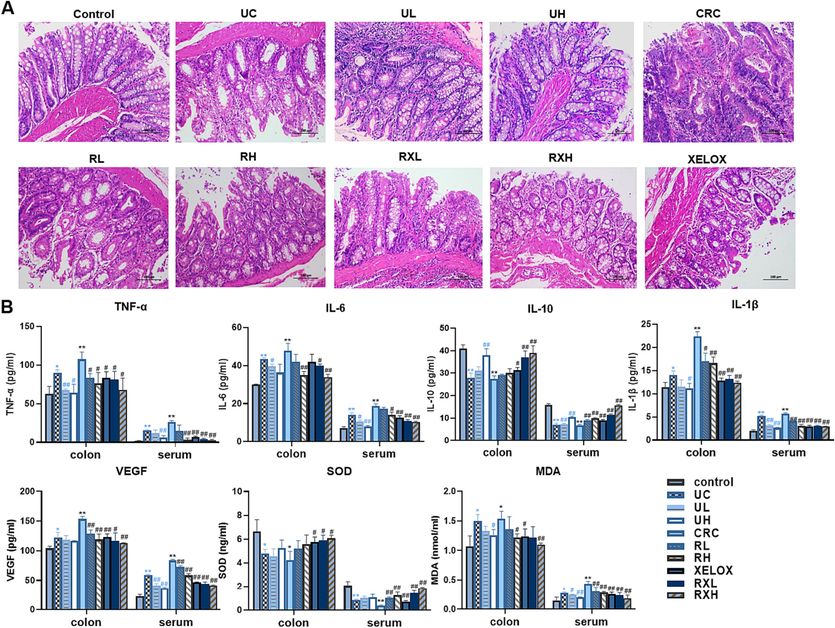

3.3 GQD intervention mitigated histopathologic injury in colon tissue caused by UC and CRC and reduce gastrointestinal adverse reactions of XELOX

The colon structure of control group was complete, and goblet cells were arranged neatly (Fig. 2A). However, colonic mucosa ulceration was serious in UC group, and pathological phenomena such as absence of colonic mucosal epithelial cells, destruction of glandular structure and disappearance of crypt structure were found. Severe colon erosion was observed in CRC group, and the pathological features were more obvious than UC group. After GQD treatment, the pathological phenomena of colonic tissue were recovered to a certain extent. Moreover, the colonic lesions of rats treated with GQD combined with XELOX were more improved than those treated with XELOX alone, indicating that GQD could effectively reduce colonic mucosal injury, assist XELOX to enhance the effect of improving intestinal lesions and reduce gastrointestinal adverse reactions of chemotherapy drugs.

H&E staining results of colon tissues (200 × magnification) (A); Bar chart of ELISA kit results for inflammatory factors, tumor factors and antioxidant indicators (B). Values shown are means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 UC vs Control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 CRC vs Control group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs UC group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs CRC group.

3.4 GQD intervention enhanced anti-inflammatory, antitumor and antioxidant activities

The activities of anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor as well as anti-oxidative of GQD were evaluated by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 2B, the pro-inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β in colon and serum increased substantially in the development of UC to CRC. After GQD treatment, significant callback effect was observed in both UC and CRC period. Meanwhile, the inflammatory factors in RXL and RXH groups were more significantly decreased than those in XELOX group. In addition, GQD also greatly increased the content of IL-10, the anti-inflammatory factor. And there was a more significant correction trend in the RXL and RXH groups than that in the XELOX group, which declared that GQD had a very strong anti-inflammatory effect, and combined treatment with XELOX might enhance the anti-inflammatory effect. Moreover, the detection results of tumor factor VEGF, antioxidant factor SOD and MDA also proved that GQD had excellent anti-tumor and antioxidant effects, and might assist chemotherapy drugs to enhance its anti-tumor and antioxidant activities. Inflammation and oxidative stress are the key factors in the toxicity and side effects of XELOX. The results above indicated that GQD had great potential in alleviating the toxicity and side effects of XELOX.

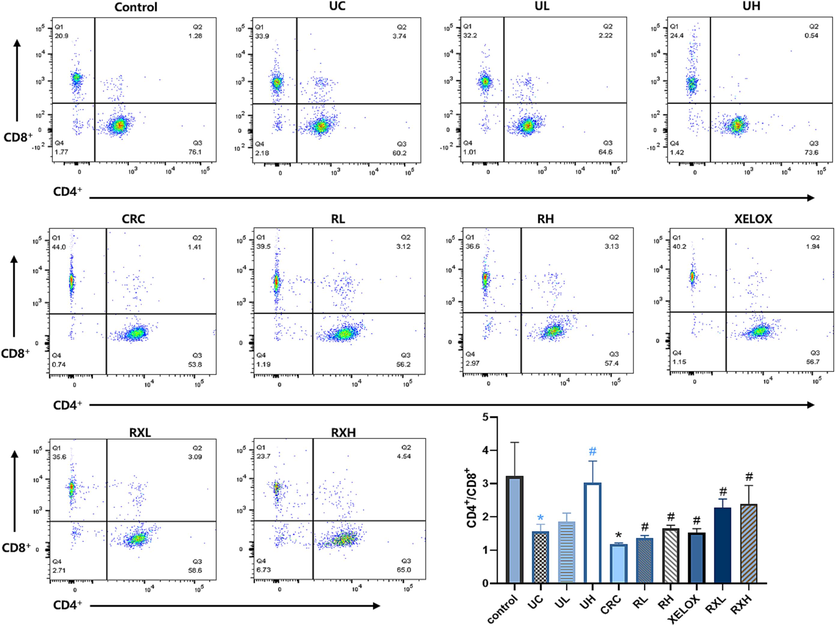

3.5 GQD intervention regulated immune response to resist the adverse reactions of XELOX

It is well known that the balance of the CD4+/CD8+ is essential for immunomodulatory effects. In this study, CD4+ and CD8+ positive cells in T lymphocytes were detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). The proportion of CD4+/CD8+ cell subsets in UC and CRC groups were prominently reduced compared with the control group (p<0.05), indicating that inflammation and tumor could damage immune function. However, after GQD intervention, the ratio of CD4+/CD8+T lymphocytes showed a dose-dependent correction and was similar to that of the control group, enunciating that GQD treatment could normalize the immune system’ balance and facilitate to play an anti-tumor role. In addition, after treatment of GQD combined with XELOX, a further reversed trend in the T lymphocytes proportion (CD4+/CD8+) was found refer to the XELOX treatment group. The data above manifested that the intervention of GQD combined with XELOX could have a positive effect on the immune system's ability to fend off unfavorable reactions.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in each group of rats. *p < 0.05 UC vs control group; *p < 0.05 CRC vs Control group; #p < 0.05 vs UC group; #p < 0.05 vs CRC group.

3.6 Intestinal microflora analysis

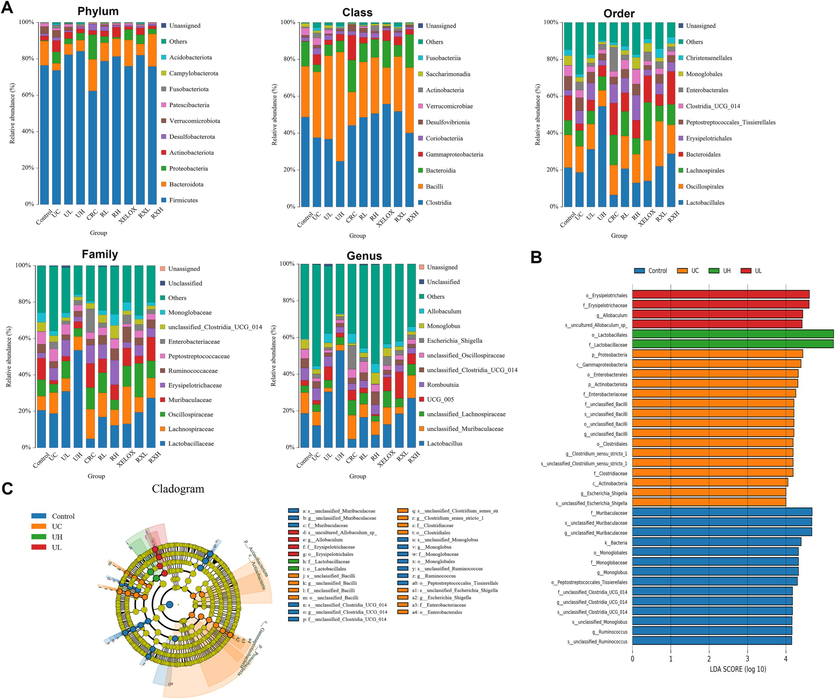

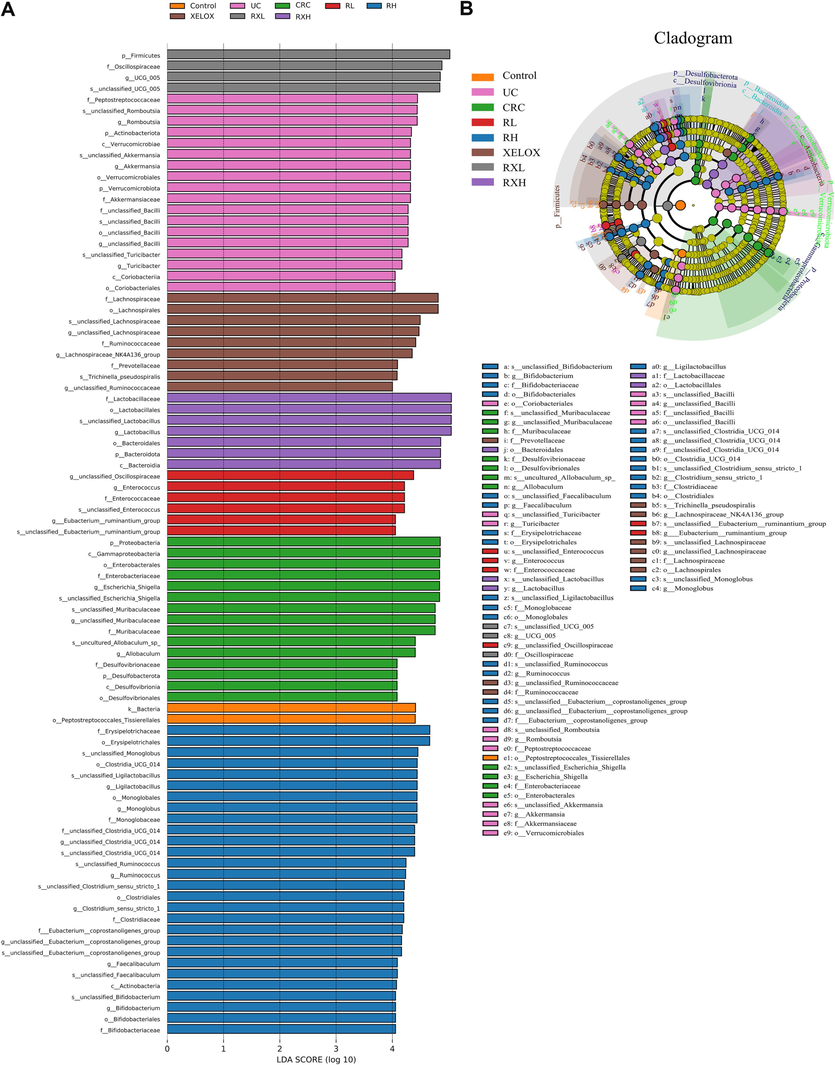

To study the impacts and molecular underpinnings of the microbial consortia on colorectal carcinogenesis, 16S rDNA sequencing technology was applied to detect the gut microbial community of rats in each group. As shown in Fig. 4A, the community distribution histogram of each group at various levels was drawn. Moreover, LDA distribution histogram and cladogram of dominant microorganisms in different groups were displayed both in Figs. 4 and 5. It could be seen from the diagram that during the evolution from UC to CRC, the intestinal microflora was obviously disturbed, manifested with Firmicutes' abundance dramatically dropped, while Proteobacteria's abundance dramatically grew at the phylum level. The microflora with high abundance were Escherichia_Shigella and Lactobacillus, and the two bacteria were common beneficial bacteria and harmful bacteria in vivo, respectively (genus level). The results showed that from UC to CRC, the abundance of Escherichia_Shigella gradually increased, and that of Lactobacillus gradually decreased. After GQD intervention, the abundance of various microflora including the above microflora was regulated towards normal levels, indicating that GQD could treat UC and CRC by remodeling intestinal microflora homeostasis and inhibit the progression of UC to CRC. What’s more, the decline trend of Escherichia_Shigella in RXL and RXH groups was more than that in XELOX group, the lactobacillus’ abundance in the RXL and RXH groups was much greater than that in XELOX group, suggesting that GQD could help restore the balance of intestinal microflora on the basic of XELOX treatment.

Distribution histogram of the top 10 community in abundance at the level of phylum, class, order, family and genus (A); Distribution histogram based on LDA of dominant microorganisms in the control, UC, UL, UH groups (B); Cladogram of dominant microorganisms in the control, UC, UL, UH groups (C).

Distribution histogram based on LDA of dominant microorganisms in different groups (A); Cladogram of dominant microorganisms in different groups (B).

3.7 Non-targeted metabolomics analysis and correlation analysis with intestinal microflora

To further explore the mechanism of GQD regulation of disease at the small-molecule level, non-targeted metabolomics study was performed on colon samples by HPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS, with.

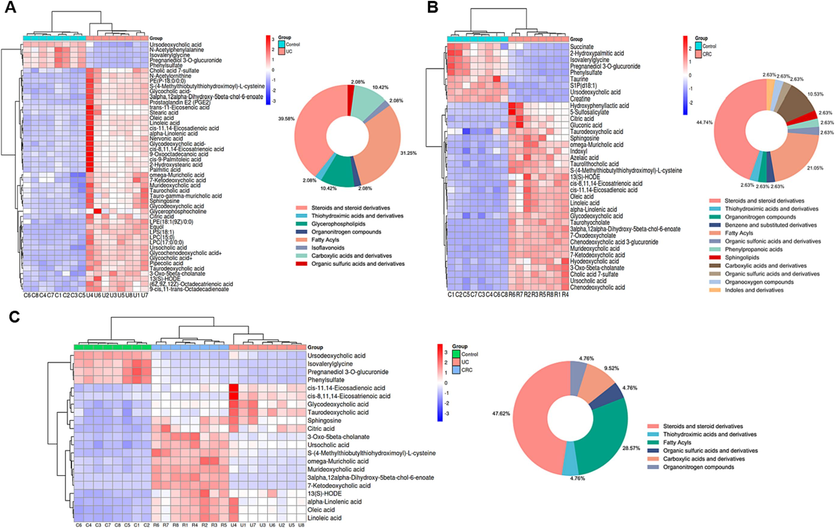

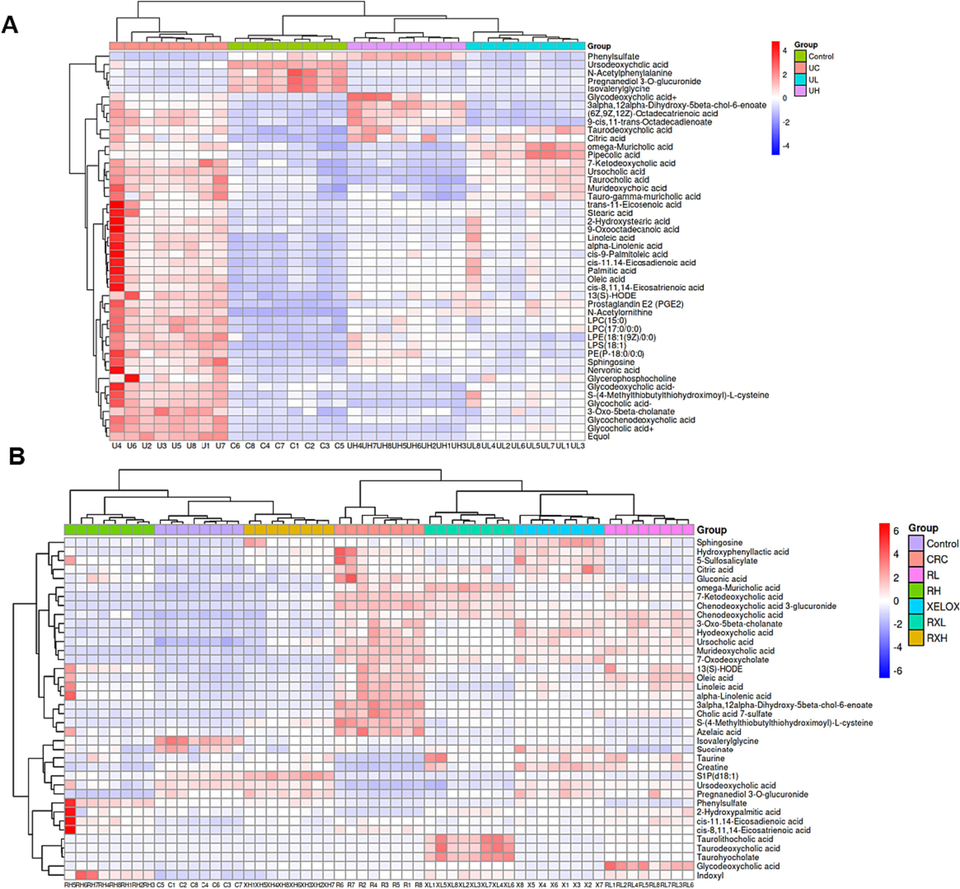

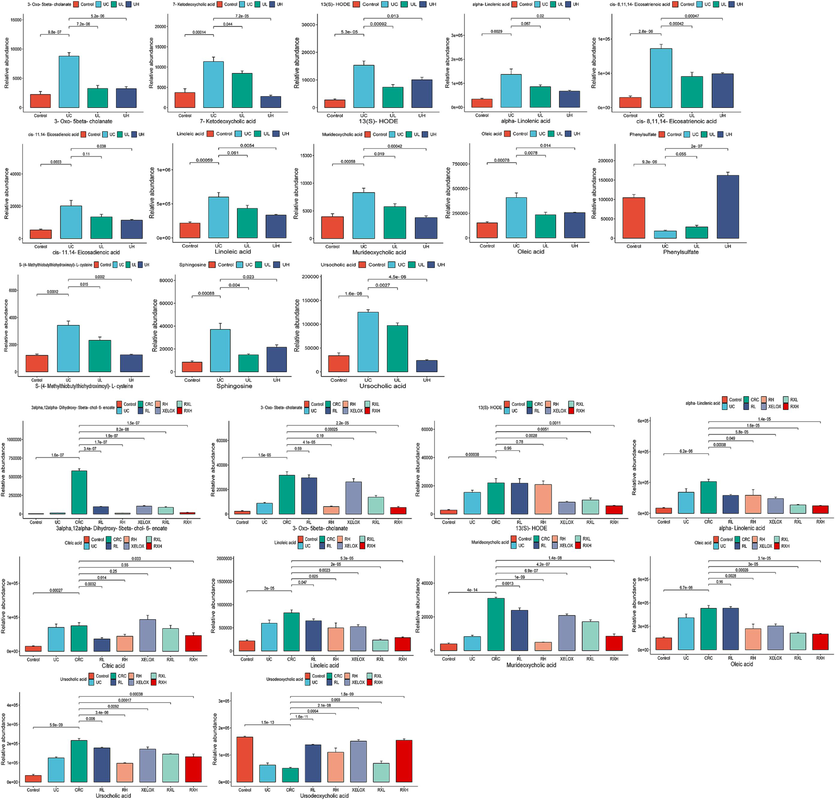

proven precision, stability, and reproducibility (Table S7). The Control, UC and CRC groups showed significant separation without overfitting (Fig. S2). Subsequently, metabolites satisfying multiple conditions were screened out (P<0.05, FC>2.0 or FC<0.5, VIP > 1.0) as potential biomarkers. In the end, 45 biomarkers were screened in the Control and UC groups, and 38 biomarkers were examined in the Control and CRC groups, among which 21 biomarkers were examined in both the UC and CRC groups. The detailed information of each biomarker was shown in Table 2. Then, the abundance of these metabolites in each group was visualized using heat maps (Figs. 6 and 7) to intuitively investigate the variation of metabolites after GQD intervention. Moreover, among the 21 metabolites associated with UC and CRC, linoleic acid, 7-ketodeoxycholic acid and other metabolites showed obvious trend of correction after treatment (p < 0.05), and the changes of these metabolites were shown in Fig. 8. UC: ulcerative colitis group, CRC: colorectal cancer group, Con.: control group, FC: Fold change. Fold1: control group/UC group, Fold 2: control group/CRC group. VIP1: control group/UC group, VIP2: control group/CRC group. ↑: increased, ↓: decrease.

No.

t(R)

ESI mode

m/z

Identification

Fomular

FC1

VIP1

FC2

VIP2

Change trend

UC/Con.

CRC/Con.

CRC/UC

1

3.3

+

130.0855

Pipecolic acid

C6H11NO2

0.42

1.17

↑

2

7.2

+

134.0593

Indoxyl

C8H7NO

0.35

1.07

↑

3

7.0

+

243.1005

Equol

C15H14O3

0.02

2.58

↑

4

3.0

+

258.1090

Glycerophosphocholine

C8H20NO6P

0.30

1.18

↑

5

9.2

+

300.2883

Sphingosine

C18H37NO2

0.23

1.53

0.24

1.21

↑

↑

↓

6

12.3

+

301.2149

(6Z,9Z,12Z)-Octadecatrienoic acid

C18H30O2

0.35

1.28

↑

7

12.9

+

303.2306

9-cis,11-trans-Octadecadienoate

C18H32O2

0.40

1.20

↑

8

10.7

+

375.2868

Murideoxycholic acid

C24H40O4

0.48

1.13

0.13

1.49

↑

↑

↑

9

11.3

+

375.2871

3-Oxo-5beta-cholanate

C24H38O3

0.26

1.55

0.07

1.68

↑

↑

↑

10

9.6

+

380.2539

S1P(d18:1)

C18H38NO5P

4.12

1.20

↓

11

9.9

+

389.2660

7-Oxodeoxycholate

C24H38O5

0.06

1.75

↑

12

10.8

+

391.2816

3alpha,12alpha-Dihydroxy-5beta-chol-6-enoate

C24H38O4

0.34

1.32

0.01

2.23

↑

↑

↑

13

10.1

+

393.2978

Chenodeoxycholic acid

C24H40O4

0.34

1.04

↑

14

11.4

+

393.2984

Hyodeoxycholic acid

C24H40O4

0.11

1.56

↑

15

9.0

+

407.2765

7-Ketodeoxycholic acid

C24H38O5

0.33

1.46

0.01

2.32

↑

↑

↑

16

8.8

+

409.2911

omega-Muricholic acid

C24H40O5

0.48

1.16

0.11

1.55

↑

↑

↑

17

9.5

+

409.2918

Ursocholic acid

C24H40O5

0.27

1.55

0.16

1.44

↑

↑

↑

18

8.6

+

450.3178

Glycodeoxycholic acid

C26H43NO5

0.21

1.58

0.32

1.12

↑

↑

↑

19

9.8

+

450.3179

Glycochenodeoxycholic acid

C26H43NO5

0.12

1.92

↑

20

8.3

+

466.3130

Glycocholic acid

C26H43NO6

0.13

1.85

↑

21

10.7

+

482.3208

LPC(15:0)

C23H48NO7P

0.33

1.33

22

8.5

+

484.3046

Taurolithocholic acid

C26H45NO5S

0.34

1.04

↑

23

10.0

+

489.2569

Cholic acid 7-sulfate

C24H40O8S

0.02

2.04

↑

24

7.8

+

498.2848

Taurohyocholate

C26H45NO7S

0.04

1.83

↑

25

8.1

+

500.2995

Taurodeoxycholic acid

C26H45NO6S

0.23

1.69

0.50

1.07

↑

↑

↓

26

12.1

+

510.3520

LPC(17:0/0:0)

C25H52NO7P

0.35

1.29

↑

27

7.5

+

516.2942

Tauro-gamma-muricholic acid

C26H45NO7S

0.42

1.09

↑

28

8.2

+

516.2947

Taurocholic acid

C26H45NO7S

0.39

1.26

↑

29

8.1

+

569.3261

Chenodeoxycholic acid 3-glucuronide

C30H48O10

0.00

2.68

↑

30

5.1

–

117.0200

Succinate

C4H6O4

2.28

1.02

↓

31

2.9

–

124.0080

Taurine

C2H7NO3S

2.75

1.12

↓

32

3.1

–

130.0627

Creatine

C4H9N3O2

2.73

1.16

↓

33

6.6

–

158.0824

Isovalerylglycine

C7H13NO3

23.16

1.96

6.81

1.64

↓

↓

↑

34

7.2

–

172.9914

Phenylsulfate

C6H6O4S

5.58

1.43

3.12

1.23

↓

↓

↑

35

3.3

–

173.0934

N-Acetylornithine

C7H14N2O3

0.15

1.48

↑

36

6.6

–

181.0507

Hydroxyphenyllactic acid

C9H10O4

0.22

1.37

↑

37

7.5

–

187.0975

Azelaic acid

C9H16O4

0.24

1.37

↑

38

4.5

–

191.0197

Citric acid

C6H8O7

0.21

1.29

0.19

1.42

↑

↑

↑

39

3.0

–

195.0511

Gluconic acid

C6H12O7

0.28

1.26

↑

40

7.2

–

206.0822

N-Acetylphenylalanine

C11H13NO3

6.21

1.47

↓

41

6.9

–

216.9809

5-Sulfosalicylate

C7H6O6S

0.07

1.82

↑

42

7.3

–

233.0426

S-(4-Methylthiobutylthiohydroximoyl)-L-cysteine

C8H16N2O3S2

0.35

1.09

0.15

1.60

↑

↑

↑

43

15.1

–

253.2167

cis-9-Palmitoleic acid

C16H30O2

0.23

1.26

↑

44

16.1

–

255.2323

Palmitic acid

C16H32O2

0.37

1.03

↑

45

14.2

–

271.2271

2-Hydroxypalmitic acid

C16H32O3

2.95

1.15

↓

46

14.9

–

277.2165

alpha-Linolenic acid

C18H30O2

0.25

1.24

0.17

1.55

↑

↑

↑

47

15.5

–

279.2320

Linoleic acid

C18H32O2

0.36

1.07

0.26

1.32

↑

↑

↑

48

16.4

–

281.2477

Oleic acid

C18H34O2

0.37

1.05

0.29

1.28

↑

↑

↑

49

17.4

–

283.2634

Stearic acid

C18H36O2

0.25

1.14

↑

50

12.6

–

295.2268

13(S)-HODE

C18H32O3

0.18

1.41

0.13

1.63

↑

↑

↑

51

17.8

–

297.2426

9-Oxooctadecanoic acid

C18H34O3

0.11

1.54

↑

52

15.7

–

299.2584

2-Hydroxystearic acid

C18H36O3

0.22

1.28

↑

53

16.0

–

305.2476

cis-8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid

C20H34O2

0.16

1.44

0.17

1.54

↑

↑

↓

54

16.7

–

307.2632

cis-11.14-Eicosadienoic acid

C20H36O2

0.26

1.22

0.41

1.06

↑

↑

↓

55

17.6

–

309.2788

trans-11-Eicosenoic acid

C20H38O2

0.14

1.39

↑

56

8.8

–

351.2166

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

C20H32O5

0.17

1.43

↑

57

19.7

–

365.3408

Nervonic acid

C24H46O2

0.18

1.37

↑

58

10.1

–

391.2835

Ursodeoxycholic acid

C24H40O4

2.66

1.09

3.26

1.27

↓

↓

↓

59

9.6

–

448.3047

Glycodeoxycholic acid

C26H43NO5

0.37

1.07

↑

60

8.2

–

464.2993

Glycocholic acid

C26H43NO6

0.39

1.06

↑

61

12.3

–

464.3121

PE(P-18:0/0:0)

C23H48NO6P

0.19

1.36

↑

62

10.9

–

478.2916

LPE(18:1(9Z)/0:0)

C23H46NO7P

0.31

1.16

↑

63

8.9

–

495.2937

Pregnanediol 3-O-glucuronide

C27H44O8

10.37

1.68

4.41

1.40

↓

↓

↑

64

11.7

–

522.2813

LPS(18:1)

C24H46NO9P

0.07

1.80

↑

Heat maps of differential metabolites between the control and UC groups (A); Heat maps of differential metabolites between the control and CRC groups (B); Heat maps of differential metabolites in both the UC and CRC groups (C); circle graphs represented the classification and proportion of differential metabolites.

Heat maps of differential metabolites between the control and UC groups after treatment (A); Heat maps of differential metabolites between the control and CRC groups after treatment (B).

Column chart of different metabolite concentrations in the control, UC, UL and UH groups (A); Column chart of different metabolite concentrations in the control, UC, CRC, RL, RH, XELOX, RXL and RXH groups (B).

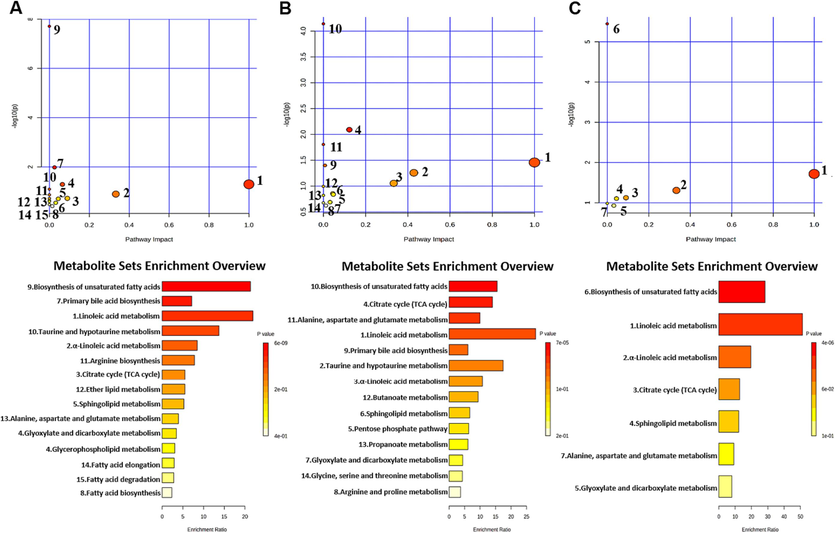

Furthermore, the MetaboAnalyst (https://www.metabo-analyst.ca/) platform was used to enrich the KEGG pathway (Fig. 9). The results showed that 15 metabolic pathways were significantly enriched during UC development. 14 metabolic pathways were significantly enriched during CRC development. 7 pathways might be affinitive to the transition from UC to CRC.

KEGG enrichment pathway maps of differential metabolites between the control and UC groups (A); KEGG enrichment pathway maps of differential metabolites between the control and CRC groups (B); KEGG enrichment pathway maps of differential metabolites related to UC and CRC (C).

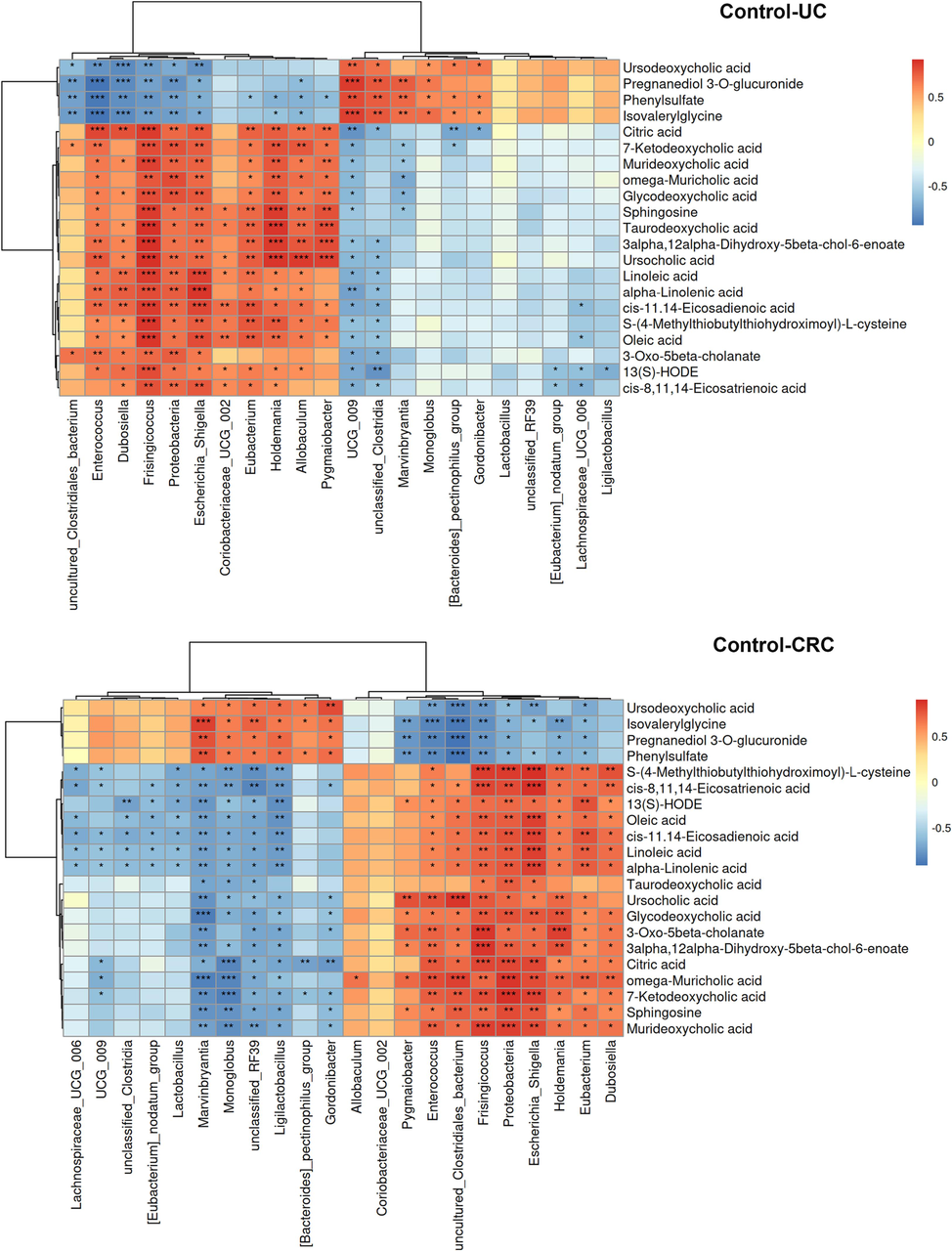

Whereafter, Spearman correlation analysis was adopted to evaluate the interaction between altered metabolites and microflora, in order to find out the key microflora and metabolites (Fig. 10). According to the Metastats analysis, among the differential microflora in control vs UC and control vs CRC, there were 22 differential microflora both in the UC and CRC groups at phylum and genus level, including Enterococcus, Allobaculum, Escherichia_Shigella, Dubosiella, Ligilactobacillus, Lactobacillus etc. And the correlation analysis was performed between them and 21 differential metabolites. The abundance of Proteobacteria, Enterococcus, Allobaculum, Escherichia_Shigella, Dubosiella and uncultured_Clostridiales_bacterium showed a gradually increasing change pattern in the development process from UC to CRC. On the contrary, the abundance of Marvinbryantia, Monoglobu, Lachnospiraceae_UCG_006, [Bacteroides]_pectinophilus_group, Gordonibacter, Ligilactobacillus and Lactobacillus showed a gradual decrease. The above bacteria were considered to have connections to the evolution of UC into CRC. Correlation analysis showed that Proteobacteria, Escherichia_Shigella and several bacteria had a significant positive correlation with unsaturated fatty acids (oleic acid, alpha-linoleic acid, linoleic acid, etc.). Ligilactobacillus, Lactobacillus and other bacteria showed significant negative correlation with unsaturated fatty acids.

Correlation heat map of key differential microflora and differential metabolites. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

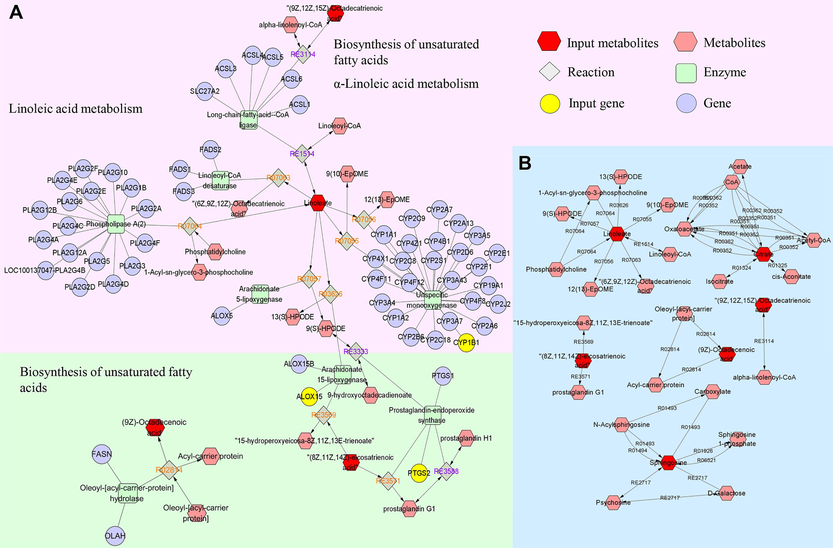

3.8 Integrated analysis of network pharmacology and metabolomics

Using the Metscape plug-in to form compound-reaction-enzyme-gene networks, 31 crucial targets from network pharmacology results and 21 distinct metabolites from metabolomics results were imported to the Cytoscape 3.10.0 (UC, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA) software, to visually related genes and metabolites of interaction (Fig. 11). Six metabolites (linoleic acid, cis-8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid, sphingolipid, α-linoleic acid, oleic acid, citric acid) as well as three targets (ALOX15, CYP1B1, and PTGS2) were identified in the network. Among them, linoleic acid and cis-8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid were key metabolites that had metabolic relationship with the targets of components in vivo. ALOX15 and CYP1B1 were core genes involved in the metabolism of linoleic acid, while ALOX15 and PTGS2 were important genes involved in the metabolism of cis-8,11,14-eicosatrienoic acid. These distinct targets and metabolites were chosen as the main metabolites and targets.

The compound-reaction-enzyme-gene networks of the key metabolites and targets (A); the network of interactions between key metabolites (B).

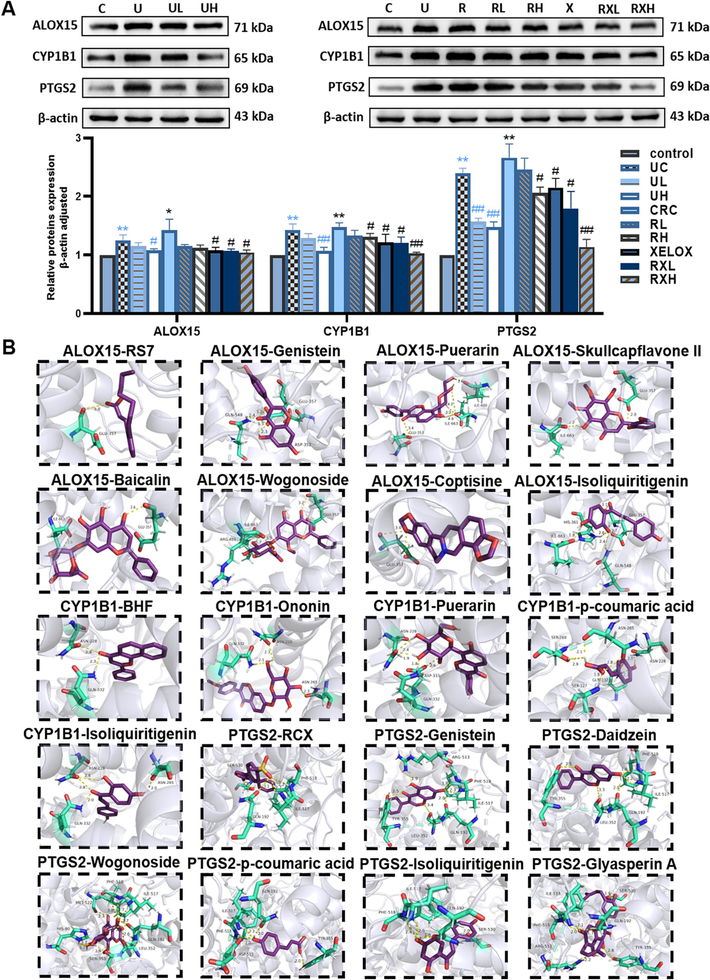

3.9 Western blot analysis of ALOX15, CYP1B1 and PTGS2 proteins

As shown in Fig. 12A, ALOX15, CYP1B1, and PTGS2 were all activated (p < 0.05) in UC and CRC groups, and each protein in CRC group was expressed more than the UC group. In addition, the expression of ALOX15, CYP1B1, and PTGS2 proteins were effectively inhibited by different concentrations of GQD (p < 0.05), especially the higher doses of GQD. Particularly, the administration of GQD combined with XELOX showed a stronger advantage in reversing the expression level of the above proteins than that of XELOX administration alone. These results indicated that the pathogenesis of UC and CRC might be accompanied by the activation of ALOX15, CYP1B1, and PTGS2 proteins, GQD exerted anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects by down-regulating these proteins, which was also a key mechanism for GQD to enhance the efficacy of XELOX.

Typical protein bands and relative expression of ALOX15, CYP1B1 and PTGS2 proteins in western blot analysis; Values shown are means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 UC vs Control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 CRC vs Control group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs UC group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs CRC group (A); Molecular docking interaction diagrams of key active components with macromolecular ligands (B).

3.10 Molecular docking result

In order to explore the pharmacodynamic substance basis of GQD in the therapy of UC and CRC, molecular docking was conducted between ALOX15, CYP1B1, PTGS2 and active components, respective. Firstly, the macromolecular ligands of ALOX15 (2p0m), CYP1B1 (3 pm0) and PTGS2 (5kir) were downloaded from the PDB database (https://www.pdbus.org/), respectively. Then, the potential active components were semi-flexible docked with the receptor proteins respectively. RS7, BHF and rofecoxib (RCX) were the positive drug of ALOX15, CYP1B1 and PTGS2, which were semi-flexible docked to 2p0m, 3 pm0 and 5kir, respectively. The results showed that GLU357 was the main active sites of 2p0m, GLN332, ASN228 were the main active sites of 3 pm0, and PHE518, ILE517, GLN192, SER530 were the main active sites of 5kir. Moreover, the binding energies to proteins of ononin, genistein, puerarin, daidzein, skullcapflavone II, baicalin, wogonoside, p-coumaric acid, coptisine, isoliquiritigenin, glyasperin A were less than −5 kcal/mol and the binding sites were similar to positive drugs, so that the above components were identified as key active components. Details of binding energy were shown in Table S8, and the results of protein–ligand interaction profile were presented in Fig. 12B and Fig. S3-5.

4 Discussion

GQD has been utilized to resist UC and other IBD since ancient times. Although several scholars have explored its therapeutic effect on CRC in recent years, the specific mechanism of action is not very clear (Fan et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2021). Furthermore, as one of the commonly used clinical treatment methods for CRC, XELOX may have certain harmful side effects and lower patients' compliance and quality of life. In clinical practice, Chinese medicine is frequently used in conjunction with chemotherapy drugs to reduce patients' adverse reactions. Our current study was the first to deeply study the pharmacodynamic effect, mechanism of action as well as pharmacodynamic material basis of XELOX combined with GQD in the treatment of CRC. HE staining results suggested that GQD combined with XELOX could effectively reduce intestinal mucosal injury and reduce gastrointestinal adverse reactions. Particularly, the contents of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, VEGF, SOD and MDA were significantly recovered after GQD treatment compared with the disease group (p<0.05), and were close to that of the control group. Therefore, the excellent performance of GQD in assisting XELOX in enhancing anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-tumor and regulating immune function was fully confirmed in this study. Inflammation and oxidative stress are major factors in nerve damage, and the low immune function is the adverse factor that leads to a series of adverse reactions. Therefore, this study suggested that GQD might counteract the toxic side effects and pain response of XELOX by controlling inflammation, oxidative stress, and boosting the immune system.

Altered microflora and metabolites is regarded as one of the most significant hallmarks of gastrointestinal disease (Lanis et al., 2017). 16S rDNA sequencing is a key technology that helps us fully understand the abundance of gut microbiome and its composition. Major advances in metabolomics technology provide us with tools to reveal the dynamic changes of endogenous metabolites at the level of small molecules in different stages of disease progression (Wu et al., 2020). The results showed that among several bacteria groups with significant increases, Proteobacteria, Allobaculum, Escherichia_Shigella, Dubosiella etc. were proved to be potential pathogenic bacteria (Hu et al., 2022, Otake-Kasamoto et al., 2022), and abnormal increases in abundance were detected in a variety of IBD and CRC groups. While Ligilactobacillus and Lactobacillus are two common beneficial bacteria, which showed a gradual decline in the evolution of inflammation into cancer. The above results indicated that the possible mechanism of UC development into CRC was to destroy the dynamic equilibrium of intestinal microecological environment, decrease the composition of helpful bacteria and increase the composition of harmful bacteria. The abundance of harmful bacteria was sensibly inhibited after GQD intervention, and the abundance of beneficial bacteria was also substantially reversed. In particular, the abundance of Escherichia_Shigella and Lactobacillus decreased and got higher even more respectively after combined administration. Linoleic acid, oleic acid, 13(S)-HODE and other 21 metabolites were different metabolites found in UC and CRC groups, and the concentrations of these substances showed a trend of gradual increase or decrease from UC to CRC. It is worth noting that after GQD combined with XELOX intervention, the correction trend is stronger than XELOX intervention. The results of correlation analysis showed that several harmful bacteria had strong positive correlation with linoleic acids and unsaturated fatty acid metabolites, but showed opposite relationship with beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus. It is suggested that the above bacteria and metabolites were deeply related to the development of UC and CRC, and might be used as potential targets for the prevention and control of UC-associated CRC, as well as key targets for the synergistic effect of GQD and XELOX.