Translate this page into:

Harmful volatile substances in recorded and unrecorded fruit spirits

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Hajduk Veljkova 3, 21 000 Novi Sad, Serbia. BRANISLAVA.SRDJENOVIC-CONIC@mf.uns.ac.rs (Branislava Srdjenović-Čonić)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The alcohol-attributable mortality is an important issue in South-Eastern Europe, whereby consumption of homemade spirits is stated to be one of the leading causes. Presence of harmful volatiles in spirits in Serbia was investigated in 26 recorded and 127 unrecorded fruit spirits, collected in 2020 and analysed using GC-FID methods. Statistical analysis confirmed higher content of ethanol, ethyl acetate, n-propanol and iso-butanol in unrecorded spirits. Regarding concentration limits proposed by the Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance, the one for methanol was exceeded in 4% of recorded and 17% of unrecorded spirits, for acetaldehyde in 4% of unrecorded and for higher alcohols only in one recorded spirit. Risk assessment, conducted using a margin of exposure approach, showed that spirit consumption, even at average level, posed a risk due to their high ethanol content. Regarding acetaldehyde, for males the risk was indicated starting from the regular drinkers only scenario (mean MOE 9937 for recorded and 9123 for unrecorded spirits) and for females who were chronic heavy drinkers of recorded (2324) or unrecorded spirits (1644). Chronic heavy drinkers of both sexes were in the risk of methanol and higher alcohols in case of exclusive consumption of unrecorded spirits.

Keywords

Fruit spirits

Ethanol

Acetaldehyde

Ethyl acetate, Methanol

Higher alcohols

1 Introduction

Alcohol use exhibits substantial impact not only on individual drinkers, but also on society at large. More than 290 000 people died in 2016 due to alcohol-attributable diseases, and 7.6 million years of life were lost due to either premature mortality or disability (WHO, 2018). For people aged 25–49 years, in 2019 alcohol use was the leading risk factor globally for attributable disability-adjusted life years (GBD, 2020). Per capita alcohol consumption (APC) in the WHO European Region is not only the highest in the world, but also almost double the global average. APC was lower in northern and southern European Member States and higher in the middle band of countries. In non-communicable disease mortality in Central Europe in 2019, 5.79% of deaths were attributable to alcohol use. In the Republic of Serbia, this percentage was slightly lower – 3.92%, with 5065.9 deaths due to alcohol consumption (IHME, 2021).

Worldwide, 44.8% of total recorded alcohol is consumed in the form of spirits. One quarter (25.5%) of all alcohol consumed worldwide is in the form of unrecorded alcohol (WHO, 2018). Production, distribution, and consumption of unrecorded alcohol is not under official quality control and regulation, thus the risk of unrecorded alcohol consumption containing potentially hazardous substances such as methanol, acetaldehyde, aflatoxins, heavy metals, toxic denaturants may be higher in comparison to recorded alcoholic beverages consumption (Okaru et al., 2019). Lima et al. (2022) emphasized that high content of contaminants in spirits was mainly related to the insufficient adoption of good production practices. The established tradition of unrecorded, homemade fruit spirits consumption has been identified as health risk driver, especially in countries located at the Balkan Peninsula, Central and Eastern Europe. As unrecorded alcohol is usually the least expensive form of alcohol available in many countries, it may contribute to higher rates of chronic and irregular heavy drinking.

Alcohol use causes substantial health loss, whereby the risk of all-cause mortality, and of cancers specifically, rises with increasing levels of consumption (GBD, 2018). Alcoholic beverages are classified as carcinogenic to humans (IARC Group 1) (IARC, 1988). Ethanol, being a genotoxic carcinogen, as well as toxic to many other health conditions, is the most hazardous toxic substance in spirits. Acetaldehyde, a potent volatile flavouring compound found in many foodstuffs is regarded as being possibly carcinogenic to humans (IARC Group 2B) (IARC 1999), but acetaldehyde associated with alcohol consumption is considered carcinogenic to humans (IARC Group 1) (IARC 2012). Additionally, chronic excessive alcohol intake induces functional defects of monocytes, whereby acetaldehyde directly affects the immune response| (Shiba et al., 2021). In alcoholic beverages, acetaldehyde may be formed by yeast, acetic acid bacteria, and coupled auto-oxidation of ethanol and phenolic compounds (Liu and Pilone, 2000). Ethyl acetate is commonly found in distilled spirits and can originate from fermentation or be created during barrel aging. In fact, the longer a spirit is aged, the more ethyl acetate it will likely have. Ethyl acetate finds particular use as a flavour enhancer in foods and pharmaceuticals because of its fruity taste when diluted. It is even included on the US Food and Drug Administration's Generally Recognized As Safe list for use as a synthetic flavouring agent. Although there is no evidence that it is carcinogenic, mutagenic, or reprotoxic, it has to be born in mind that ethyl acetate is rapidly hydrolysed to ethanol and acetic acid, and thus can attribute to ethanol toxicity when it comes to alcoholic beverages (Estevan and Vilanova, 2014; FDA, 2021; Marino, 2005). Higher alcohols occur naturally in alcoholic beverages as by-products of alcoholic fermentation. The major higher alcohols found in alcoholic beverages are 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 2-butanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol. An animal study on rats revealed that one type of an Indian country liquor rich in higher alcohols had increased toxicity compared to the same dose of pure ethanol (Lal et al., 2001). Higher alcohols have been speculated as a cause of unrecorded alcohol toxicity in Eastern Europe (hepatic cirrhosis) (Lachenmeier et al., 2008). Methanol has been considered as the most common cause for surrogate alcohol toxicity (Lachenmeier et al., 2007; Paine and Davan, 2001). In 2012, U.S. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA, 2012) added methanol to the list of chemicals that cause developmental toxicity (OEHHA, 2012). Although unrecorded fruit spirits contain appreciable quantities of methanol, often at levels much higher than in commercially produced spirits, the blood methanol levels achieved even in case of heavy drinking will not be sufficient to cause acute toxicity. However, this does not exclude the possibility of so far unknown adverse consequences of chronic consumption (Muhollari et al., 2022). For some of the aforementioned substances found in spirits, legal requirements have been established regarding their content. Within the EU, according to the Regulation 2019/787 (EU, 2019), which is also transposed in the regulation of the Republic of Serbia, fruit spirit is a spirit drink that meets, among others, the following requirements: alcoholic strength by volume shall range from 37.5 to 86%; volatile substance content should be equal or over 200 g/hL of 100% vol. alcohol; maximum methanol content shall be 1000, 1200 or 1350 g/hL of 100% vol. alcohol, depending on the type of fruit. Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance project (AMPHORA), along with limitation for methanol content at 1000 g/hL of 100% vol. alcohol, proposed maximum chemical testing limits for additional substances with potential to pose a public health risk, in recorded and unrecorded alcohol products (g/hL of 100% vol. alcohol): higher alcohols (sum) 1000; ethyl acetate 1000; acetaldehyde 50. (IARD, 2015).

In the Republic of Serbia, there has been a long tradition of, not only drinking but also, homemade production of different kinds of alcoholic beverages, the most common kinds of spirits being those made of plums, grapes and stone fruits. Therefore, the aims of this study were: (1) to determine the content of acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, methanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, n-butanol, isoamyl alcohol, and n-amyl alcohol in recorded and unrecorded fruit spirits available in the northern Serbian region Vojvodina, (2) to evaluate compliance of investigated fruit spirits with legal requirements, as well as limits proposed by the AMPHORA, (3) to assess the health risk caused by consumption of fruit spirits, and (4) to get insight into the differences between recorded and unrecorded fruit spirits regarding the aforementioned items (volatiles concentrations, compliance and risk).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and chemicals

Acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, n-propanol, isobutanol, n-butanol, isoamyl alcohol, and n-amyl alcohol for UV, IR, HPLC, ACS were purchased from AppliChem Panreac ITW Companies, Germany, as well as NaCl for analysis, ACS, ISO. Deionized water (ASTM II) from Merck Millipore: Elix Essential.10 ware system was used for all dilutions.

2.2 Preparation of standard solutions

Working solution (100 mL) containing a mixture of acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, methanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, n-butanol, isoamyl alcohol, and n-amyl alcohol in concentration of 9.75, 18.00, 98.75, 12.50, 12.50, 12.50, 37.50 and 10.00 g/L p.a. respectively was prepared by dissolving adequate volume of acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, methanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, n-butanol, isoamyl alcohol, and n-amyl alcohol in 40% ethanol (v/v). Calibration solutions were prepared by dilution of the working solution with 40% ethanol (v/v) in the range presented in the Table 2. For the ethanol determination, a 100 mL of 40% (v/v) ethanol was prepared. The sample preparation procedure (subsection 2.4.) was carried out for each calibration solution. *Accuracy range based on low, medium and high concentration recovery check; R2-correlation coefficient; LOQ-limit of quantification.

Spirits

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

Scenario 3

Scenario 4

average consumption

regular drinkers only

chronic heavy drinkers (A)

chronic heavy drinkers (B)

recorded

unrecorded

recorded

unrecorded

recorded

unrecorded

recorded

unrecorded

litres of pure alcohol per capita yearly

Men

3.89

3.00

5.28

4.07

5.84

4.50

27.76

27.76

Women

0.86

0.66

1.85

1.43

3.90

3.00

18.50

18.50

Both sexes

2.34

1.80

3.89

3.00

Analyte

Concentration range (mg/L p.a.)

Calibration equation

R2

Accuracy* (recovery, %)

Precision RSD (%)

LOQ (mg/L p.a.)

Intra-day precision

Inter-day precision

acetaldehyde

48.75–975

y = 0.0016x + 0.0348

0.9984

87.5–109.6

9.48

6.64

48.75

ethyl acetate

18–1800

y = 0.0027x + 0.0211

0.9972

85.3–105.4

6.53

5.07

18

methanol

98.75–9875

y = 0.0005x + 0.0381

0.9995

89.9–114.6

7.33

4.66

98.75

n-propanol

12.5–1250

y = 0.0010x + 0.0161

0.9993

86.6–114.3

6.68

4.98

12.5

iso-butanol

12.5–1250

y = 0.0013x + 0.0198

0.9985

90.7–110.4

5.90

5.35

12.5

n-butanol

62.5–1250

y = 0.0009x + 0.0219

0.9919

93.0–106.8

7.68

5.19

62.5

iso-amyl alcohol

37.5–3750

y = 0.0008x + 0.0281

0.9992

96.5–112.1

6.84

4.83

37.5

n-amyl alcohol

50–1000

y = 0.0007x + 0.0074

0.9991

89.1–112.9

7.66

5.08

50

ethanol

/

/

/

/

1.56

1.67

/

2.3 Fruit spirit samples

Out of 153 fruit spirit samples collected during 2020 in Vojvodina (Serbia), 26 with tax stamp were marked as recorded (commercial, made in Serbia), whereas 127 produced in private homes or small scale distilleries and obtained mainly directly from the producers were marked as unrecorded (non-commercial). Concurrently, information related to the raw fruit used for their production and identification of the producer were gathered. Samples were delivered to the laboratory correctly sealed in glass bottles, labelled with the identification number, stored in dark at room temperature and opened right before analysis. Spirits were grouped according to the source fruit: plum (n = 47), apricot (n = 23), pear (n = 18), quince (n = 12), apple (n = 10), grape pomace (n = 24) and miscellaneous (n = 19) (elder, peach, mulberry, strawberry, blackberry, cherry plum, cherry).

2.4 Sample preparation

For determination of volatiles, headspace sample solution was prepared as a mix of 1 mL of the calibration or sample solution with 25 μL of the internal standard (12.5 mg/mL methyl isobutil ketone) and 0.5 g NaCl, in 20 mL headspace vial, immediately crimp sealed. For ethanol determination, calibration solutions and samples were diluted with deionized water by a factor of 80, directly into the vial.

2.5 HSS/ALS-GC-FID analysis

The analytical method was based on method previously published by Srdjenovic et al. (2019). The instrumentation used for the analysis consisted of a gas chromatograph (7890B GC System, Agilent Technologies) equipped with automatic liquid and headspace samplers (7697A Headspace Sampler, Agilent Technologies), DB-WAX-UI analytical column (30 m × 0.250 mm × 0.25 µm, Agilent Technologies), and flame ionisation detector (FID). Ultra-high purity helium was used as the carrier gas. Temperature program, instrumental and analysis parameters of HSS-GC-FID method, used for all analytes except ethanol, as well as ALS-GC-FID method, used for ethanol analysis, are presented in the Supplementary material, Tables S1 and S2, respectively. Quantification of the analytes was based on the internal standard procedure, except for ethanol, when single-point external calibration was used.

2.6 Method validation

The procedures used for the method validation were those described in the International Conference of Harmonization Guidelines (ICH, 1994). The selectivity of the method was checked based on the chromatograms of calibration solution, one unrecorded and one recorded fruit spirit. The linearity of a calibration curve constructed over seven concentration points, run in duplicates, was estimated for each analyte presented in Table 2. The accuracy was investigated using calibration solutions with low, medium and high level of analytes, and one spirit sample spiked with low, medium and high level of analytes, all analysed in triplicates. Intra- and inter-day precision (n = 3) was evaluated using calibration solution containing medium level of analytes, while in case of ethanol determination a real sample was used. The signal to noise ratio of 10 or more was the criterion for determination of the limit of quantification (checked on the lowest calibration concentration).

2.7 Compliance evaluation and risk assessment

The compliance of the investigated samples was evaluated based on acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, methanol, and higher alcohols content, by comparison of their determined levels with the limits defined by the Regulation 2019/787 (EU, 2019) and/or proposed by the AMPHORA project (Table S3) (IARD, 2015).

For the risk assessment, a margin of exposure (MOE) approach was used to evaluate possible safety concerns arising from hazardous volatile substances present in fruit spirits. The MOE was calculated as a ratio of a toxicological threshold value and an estimated daily exposure. No observed adverse effect levels (NOAEL) and, exceptionally for methanol, lower one-sided confidence limit of benchmark dose (BMDL), used as the toxicological thresholds, were those presented in Table S4. Estimated daily exposure to each substance of interest (mg/kg bw per day) was calculated by multiplying determined concentration of a substance in a fruit spirit (mg/L p.a.) and alcohol consumption per day (L of pure alcohol per day), and further dividing the product with body weight (kg) (data taken from the European Food Safety Authority: 82.0 kg for man, 67.2 kg for woman, and 73.9 kg for both sexes average) (EFSA, 2012). If the amounts of specific volatiles in examined samples were lower than their respective LOQs, for the purpose of the risk assessment one half of the stated LOQ was taken. For the daily alcohol consumption of Serbian consumers, the following scenarios were employed: (1) average consumption on the population level (per capita consumption averaged across the entire population aged 15 + ), (2) regular drinkers only (total population aged 15 + minus abstainers), (3) chronic heavy drinkers version A (considering share of recorded and unrecorded alcohol consumption), and (4) chronic heavy drinkers version B (considering exclusive consumption of recorded or unrecorded spirits). All input data necessary for the calculation of alcohol consumption volumes, presented in Table 1, were taken from the WHO Global status report on alcohol and health (WHO, 2018).

MOE evaluation criteria were those defined by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). For genotoxic carcinogens, an MOE of 10,000 is indicated as the cut-off point for public health safety. However, when toxicological data are based on human studies and for a substance that is not considered an essential part of the diet (as ethanol), a cut-off point of 1,000 is considered acceptable. For health issues other than cancer (relevant for methanol, ethyl acetate, and higher alcohols), EFSA indicates an MOE of 100 as the cut-off point (CORDIS, 2013) Assuming additional risks owing to similar mechanisms of action, combined margin of exposure (MOEc) was calculated for ethanol and acetaldehyde, as well as for the group of higher alcohols (Bujdosó et al., 2019b).

All of the obtained data were processed by Microsoft Office Excel (v2019) and Statistica v12.5 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK). Descriptive statistical parameters, such as mean, median, interquartile range, selected percentiles, were calculated for variables of interest. Furthermore, the distribution of specific variables was presented by Box plot graphs. The differences in concentration of particular alcohols between groups of recorded and unrecorded products was assessed by application of Mann-Whitney U test, while for the differences in occurrence Chi-square test was applied, whereas p = 0.05 was taken as significance level.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Method validation

Applied HSS-GC-FID method enabled simultaneous determination of acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, methanol, isopropanol, isobutanol, n-butanol, isoamyl and n-amyl alcohol in fruit spirits. Chromatographic separation and selectivity of the method are documented in the Supplementary material, Figure S1, showing the chromatograms of the standard and one real sample solution. Method performance, meaning linearity correlation coefficient, accuracy, precision and limit of quantification confirmed its fitness for determination of all selected analytes (Table 2).

3.2 Evaluation of volatiles occurrence and compliance assessment

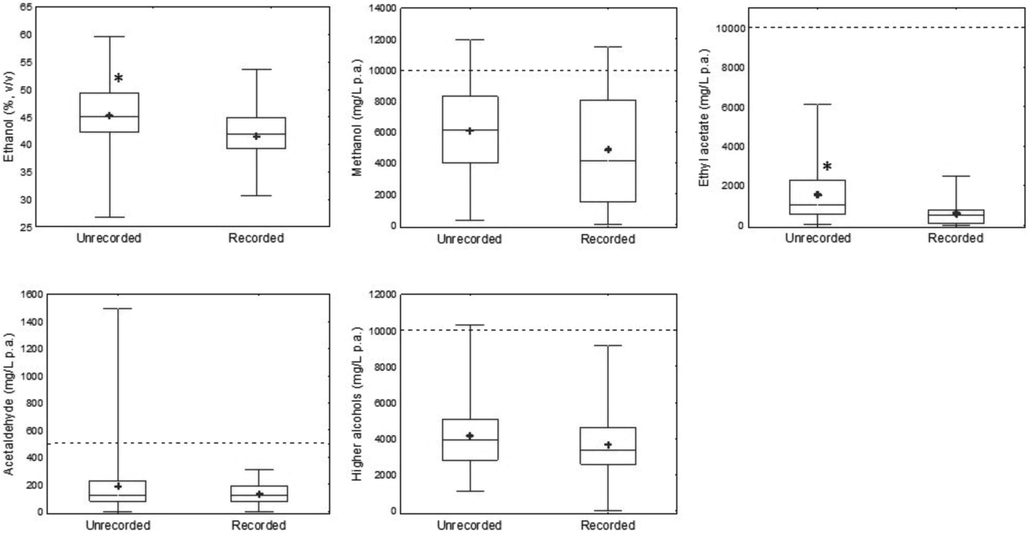

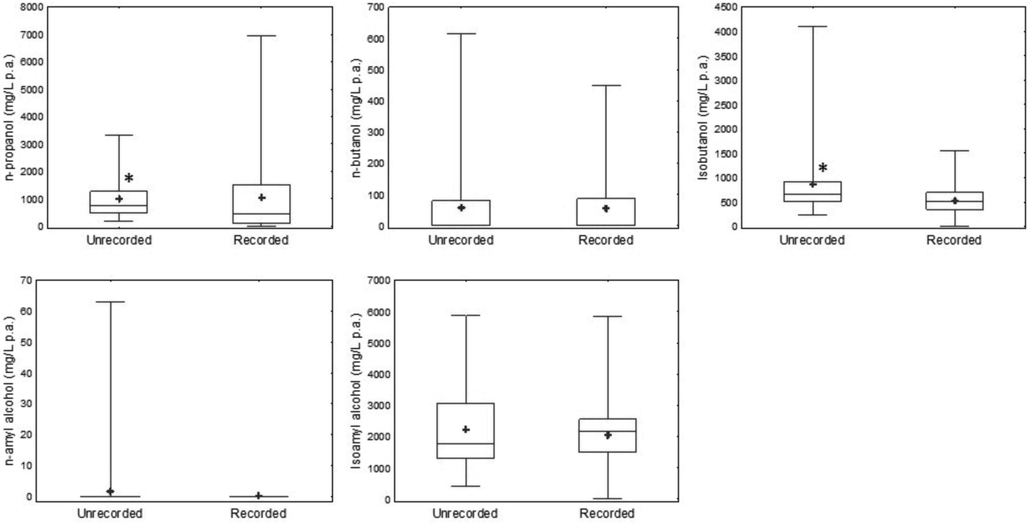

The analytically determined content of volatiles (apart of ethanol) was expressed in mg/L of pure ethanol to enable comparability of their concentrations in spirits with different alcoholic strength. Contents of ethanol (%, v/v), acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate, and methanol are presented in Fig. 1, as well as a sum of higher alcohols, whereas content of individual higher alcohols is presented in Fig. 2.

Comparison of measured content of volatiles in unrecorded and recorded spirits. *p < 0.05; ------------ AMFORA limit; - median, + mean; □ 25%-75%; I 1%-99%.

Comparison of measured content of individual higher alcohols in unrecorded and recorded spirits *p < 0.05; ------------ AMFORA limit; - median, + mean; □ 25%-75%; I 1%-99%.

The concentrations of ethanol (U = 1032, p = 0.002), ethyl acetate (U = 825, p < 0.001), n-propanol (U = 1208, p = 0.031) and iso-butanol (U = 1049, p = 0.003) were significantly higher in unrecorded spirits than those in their recorded counterparts. In case of n-amyl-alcohol only three unrecorded samples had content of n-amyl-alcohol above the LOQ. Frequency of occurrence above LOQ for n-butanol was 30% for unrecorded and 31% for recorded spirits, while for all other analysed higher alcohol these percentages were 100% for unrecorded spirits and around 90% for the recorded ones. The differences were statistically significant in the case of n-propanol (χ2 = 9.89, p = 0.001), iso-butanol (χ2 = 9.89, p = 0.001) and iso-amyl-alcohol (χ2 = 9.89, p = 0.001), as well as in the case of sum of higher alcohols (χ2 = 4.91, p = 0.026). Lower percentages of occurrence for acetaldehyde, ethyl acetate and methanol were observed for recorded spirits in comparison to the unrecorded ones (85, 92, and 88% vs 94, 100 and 100% respectively); these differences were statistically significant for ethyl acetate (χ2 = 5.35, p = 0.020) and methanol (χ2 = 14.94, p < 0.001).

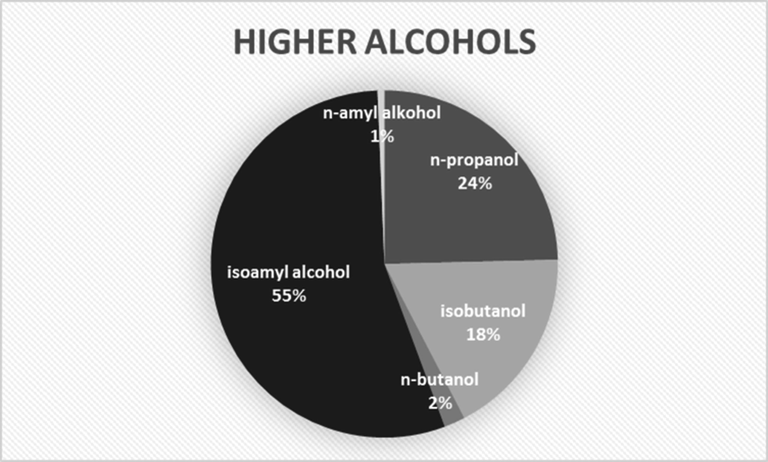

Finding of statistically higher ethanol content of unrecorded spirits (Fig. 1a) was in line with the results of Kokkinakis et al. (2020), who analysed recorded and unrecorded traditional Greek spirit beverages, and made a suggestion that producers of recorded products have better control over their production process than the individuals producing unrecorded spirits. Overall, all analysed fruit spirits, recorded and unrecorded ones, met the European Legislation requirement for maximum ethanol content (<86% by volume). Regarding methanol content, only 3 samples of unrecorded fruit spirits did not meet EU requirement for a maximum methanol content (EU, 2019). On the other hand, the AMFORA limit for methanol was exceeded in 17% of unrecorded samples, as opposed to the only 4% of recorded ones. Although tendency of higher methanol content in unrecorded spirits was noticed (6088 ± 3107 mg/L p.a. versus 4873 ± 3609 mg/L p.a. in recorded spirits), no statistical significance of the difference was confirmed (Fig. 1b). Mean methanol content of unrecorded spirits was very close with the one obtained in the study conducted in Bosnia and Hercegovina (6880 ± 3400 mg/L p.a.), a neighbouring Balkan country with similar habits of consumption and production of home-made spirits (Marjanovic et al., 2019). In respect of acetaldehyde, AMPHORA threshold was exceeded in only 4% of unrecorded spirits. Importantly, ethyl acetate content of all analysed samples was far below AMFORA limit, regardless the difference between recorded and unrecorded spirits (Fig. 1b). Recommendation related to the content of higher alcohols was not met by only one recorded spirit (Fig. 1d). Isoamyl alcohol contributed the most in the total content of higher alcohols (55%), followed by approximately 2.5- and 3-fold lower amounts of n-propanol and isobutanol, respectively, as presented in Fig. 3. n-Amyl alcohol was quantified in only three samples, in amounts slightly above the LOQ of 50 mg/L p.a., and around 200-fold lower than AMFORA limit for the sum of higher alcohols (Fig. 2d). Bujdoso et al. (2019b), who analysed recorded and unrecorded spirits in Hungaria, noticed statistical difference in the content of the sum of aliphatic alcohols excluding ethanol. However, in the study of Bujdoso et al. higher alcohols were calculated and assessed together with methanol as the group named „other aliphatic alcohols”, while in the present study they were evaluated separately, in line with the presentation of AMFORA recommendations. It was interesting to note that three samples, all from the same producer, were free of methanol and higher alcohols. As it is defined by the Regulation 2019/787 (EU, 2019), fruit spirits should contain at least 200 g of volatile substances per hL of pure alcohol. Although there are hundreds of substances contributing to the volatile fraction of fruit spirits, higher alcohols are quantitatively substantial contributors and, thus, their absence, supported with absence of methanol, suggest synthetic origin of the products. The fact that all three samples were officially placed on the market indicates that official control scheme in place in the Republic of Serbia is not fully efficient.

Share of the average content of individual higher alcohols in the total average content of higher alcohols.

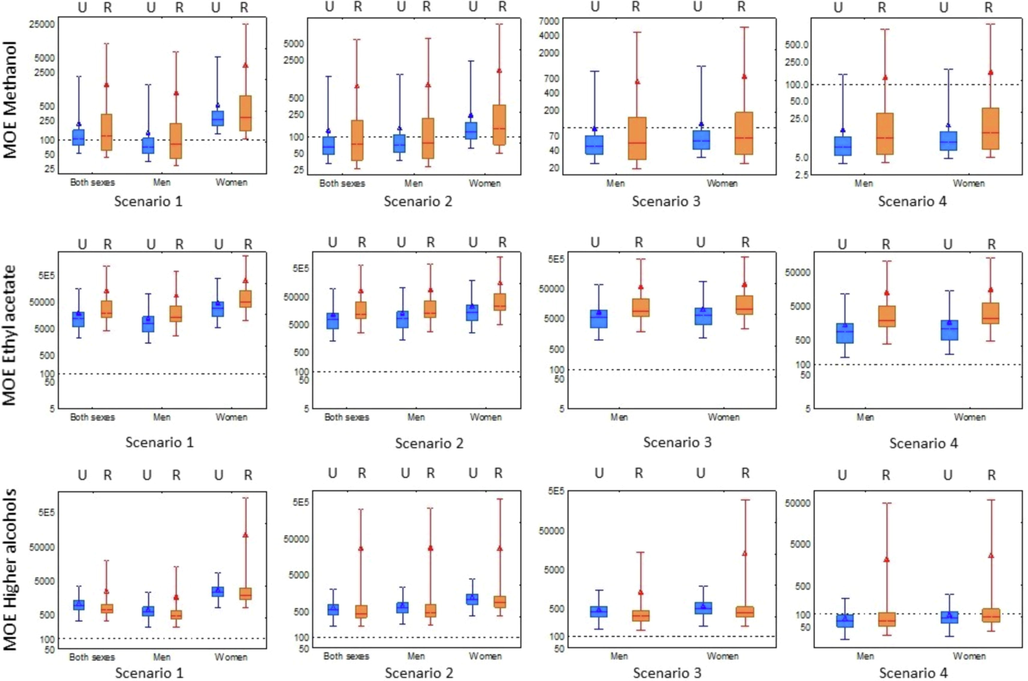

3.3 Risk assessment

The further goal was to evaluate whether the exposure to harmful volatile substances through recorded and unrecorded fruit spirits poses health risk to the consumers, taking into account gender specific consumption of unrecorded and recorded spirits. It should be noted that n-amyl alcohol, due to its very low occurrence frequency, as well as the lack of sufficiently reliable toxicological threshold, was omitted from the risk assessment.

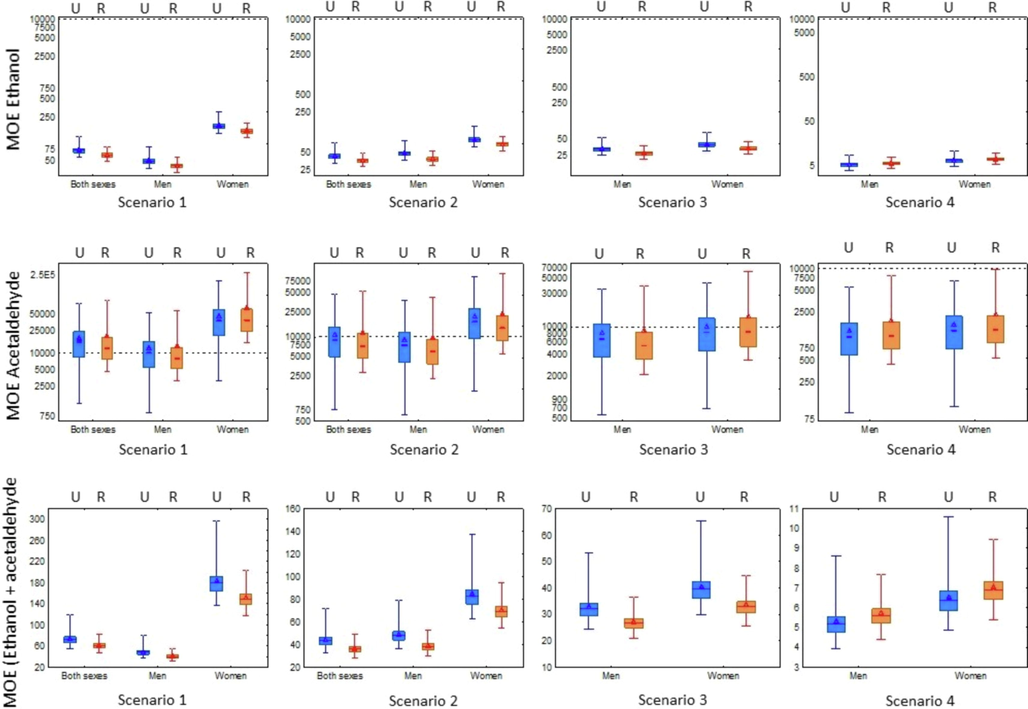

As expected, the lowest MOE values were obtained for ethanol. Exposure to ethanol caused by any of the samples was hazardous, even in the most conservative population average consumption scenario (Fig. 4a, Table 3), where mean MOE for men, as well as for both sexes, was an order of magnitude below the cut-off point, whereas mean MOE for women was approximately five-fold bellow the cut-off, with only slight differences regarding recorded or unrecorded samples (Fig. 4a). These findings are in accordance with the ones of Lachenmeier et al. (2012), who identified ethanol as the most important carcinogen in alcoholic beverages.

Comparison of margin of exposure (MOE) of carcinogenic volatiles in unrecorded (U) and recorded (R) spirits. ------------ cut-off point; - median, Δ - mean; □ 25%-75%; I 1%-99%.

Analyte - sample type

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

Scenario 3

Scenario 4

both sexes

men

women

both sexes

men

women

men

women

men

women

acetaldehyde unrecorded/recorded

31/35

47/65

5/0

53/69

64/77

27/31

69/77

57/58

100/100

100/100

etanol unrecorded/recorded

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

ethanol + acetaldehyde unrecorded/recorded

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

100/100

ethylacetate unrecorded/recorded

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

methanol unrecorded/recorded

46/46

73/58

0/0

76/65

73/62

33/46

80/65

76/65

97/85

96/85

higher alcohols unrecorded/recorded

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

0/0

77/73

65/58

Regarding acetaldehyde, a proportion of the samples was responsible for MOEs below 10 000 in all consumption scenarios, excluding the female population consuming average volumes of recorded spirits (Table 3). In case of chronic heavy drinkers of both sexes, MOEs dropped below the cut-off point for more than 50% of both types of spirits in version A, while in version B the group of hazardous samples was fully saturated (100%). Across the consumption scenarios, higher proportion of recorded spirits exerted toxic potential (Table 3). If the mean MOE was considered, both recorded and unrecorded spirits indicated a potential risk for men starting from the regular drinkers only scenario (9937 and 9123, respectively) and for women only in the heavy drinking scenario version B (2324 and 1644, respectively). (Fig. 4b). In the worst case scenario, mean MOEs were around nine-fold bellow the cut-off value. Presented findings are in line with the study of Kokkinakis et al. (2020), where the mean MOE of acetaldehyde was found to be well below 10 000, with slightly lower value for the in bulk spirits in comparison with the bottled ones.

Considering the similar mechanisms of action of ethanol and acetaldehyde, in order to evaluate cumulative risk, combined margin of exposure (MOEc) was calculated (Fig. 4c). Obtained MOEc levels revealed that the risk of acetaldehyde was minor compared with that of ethanol, similarly to the findings of Kokkinakis et al (2020). As previously concluded by Rehm et al. (2014), ethanol was the most harmful ingredient of alcohol beverages, and health consequences due to, in this case, acetaldehyde, in fruit spirits were scarce.

As for the non-carcinogenic volatiles, most worrying situation was noticed for methanol. Regarding individual samples, if consumed by females in population average volumes, not one of them caused an MOE below 100 (Fig. 5a). However, rise of the consumption to the regular drinkers level, resulted with MOEs lower than 100 for one third of unrecorded and almost a half of recorded samples. When males were considered, there was no practical difference between those two scenarios, whereas a higher proportion of unrecorded spirits was related to hazardous methanol exposure in comparison with recorded ones (73 vs 58% and 78 vs 62%, respectively) (Table 3). Although no statistically significant difference was noticed between unrecorded and recorded samples regarding the content of methanol, unlike recorded spirits, where mean MOE did not drop below 100 in any of the consumption scenarios (the mean MOE ranged from 3550 in scenario 1 to 134 in scenario 4), mean MOE for unrecorded spirits indicated potential risk in heavy drinking scenario version A (97, men) and B (15, men, and 19, women) (Fig. 5a). High methanol exposure through the consumption of unrecorded spirits, represented with 95th percentile of exposure, indicated risk even at population average consumption level (mean MOE 60, both sexes, and 40, men).

Comparison of margin of exposure (MOE) of non-carcinogenic volatiles in unrecorded (U) and recorded (R) spirits. ------------ cut-off point; - median, Δ - mean; □ 25%-75%; I 1%-99%.

With respect to the sum of higher alcohols, only in chronic heavy drinkers scenario version B high proportion of both recorded and unrecorded spirits exerted a risk for both men (77%) and women (62% of former and 65% of latter) (Table 3). When mean MOE was considered, in the risk were exclusive chronic heavy consumers of unrecorded spirits, both men and women (Fig. 5c). Isoamyl alcohol contributed the most in cumulative risk of higher alcohols, driven with its higher content (over the half of the sum of higher alcohols; Fig. 3), but also due to the considerably higher toxicity, compared with other quantitatively significant higher alcohols, n-propanol and isobutanol (Table S4). Unlike Hungarian (Bujdosó et al., 2019a; Bujdosó et al., 2019b) and Greek studies (Kokkinakis et al., 2020), no statistically significant difference between recorded and unrecorded spirits produced in the Republic of Serbia was observed regarding the content of volatiles in general and consequent health risk, although unrecorded spirits, to some extent, did pose higher risk.

Finally, neither men nor women were in the risk of the chronic negative effects of ethyl acetate contained in any of the samples, regardless the type of spirit and consumption scenario (Fig. 5b, Table 3).

The fact that prevalence of heavy episodic drinking in the Republic of Serbia is rather high, especially in males (even 46.3% in general adult population and 62.7% among drinkers only, while for females respective prevalence is 12.9 and 27.4%) pushes regular drinkers with episodes of heavy drinking closer to chronic heavy drinkers. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders is 5.9% for both sexes, and even 9.9% for males, with major share of alcohol dependence (3.4 and 5.5%, respectively) (WHO, 2018). Health consequences for Serbian adult population, estimated by the WHO in the latest Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, are expressed as 2263 alcohol attributable deaths per year, comprising contribution of liver cirrhosis (25%), road traffic injuries (11%) and, dominantly, cancer (64%) (WHO, 2018). Therefore, a call for a strategy to prevent health concerns caused by alcohol intake is in place. In that sense, Republic of Serbia has already established excise tax on alcoholic beverages, national legal minimum age (18), as well as restriction on hours and places (petrol stations are not included) for sales of alcoholic beverages, along with the prohibition of sale to intoxicated persons, national maximum legal blood alcohol concentration when driving a vehicle (0.03%), legally binding regulations on alcohol product placement, advertising, sales promotions and sponsorship. On the other hand, health warning labels on alcohol containers/advertisements are not legally required. National government supports community actions, but, obviously, it will take much more, especially in the era of pandemic of Corona virus, when substantial increase in alcohol consumption is widespread phenomenon (Davies et al., 2022; Manthey et al., 2021; Pachi et al., 2021).

3.4 Study strengths, limitations and on-going efforts

Although data related to the content of harmful volatile substances in fruit spirits in the Republic of Serbia are generally very scarce, the study mainly focused on unrecorded spirits (1 2 7), whereas recorded ones were much less represented. The number of recorded samples (26) was high enough to include majority of official brands and producers with significant presence on the market, but high percentiles of concentration and exposure should be considered only as an indication. However, inclusion of recorded samples enabled insight into the possible differences between recorded and unrecorded spirits. Conditionally homogenous group of fruit spirits, although produced in a similar way but from very versatile fruits, facilitated the comparison, as other alcoholic beverages, such as wine, beer and grain spirits, generally have low concentration of methanol and higher alcohols. It should be noted that huge differences exist in methanol and higher alcohols content even among fruit spirits, depending on the source fruit. Therefore, fruit spirits made of plums, pears and apricot which typically have high content of methanol and higher alcohols, were represented in very similar proportions in recorded and unrecorded group of samples (38 and 42%, respectively). Rather high share of these spirits is conditioned by high production rate of plums in the Republic of Serbia, as well as their popularity. Analytical investigation was conducted using validated, fit for purpose method, with eight volatile substances of toxicological importance included into the method scope. Considering consumption data, several scenarios were used to span the probable range of alcohol intake, taking into account general adult population (over 15 years), regular drinkers and chronic heavy drinkers, as well as gender differences. With respect to the toxicological threshold doses used for MOE calculation, uncertainties specifically related to NOAELs have to be acknowledged, due to the fact that these values do not provide information on dose-response relationship, in contrast to BMDLs. Finally, although presented results are limited to harmful volatiles, broader on-going study includes investigation of other substances of interest, such as elements and ethyl carbamate, with an aim to enable a more comprehensive insight into the toxicological potential of fruit spirits. A specific problem of the reliable identification of the source fruit in unrecorded spirits also requires attention. Although less justified from the toxicological aspect, that is of special importance for a proper correlation of content of volatile substances and spirits' source fruits, particularly interesting in case of methanol. Therefore, interpretation of the results in that sense was postponed until finalisation of on-going analytical investigation directed towards finding of marker compounds for a specific fruit. Last but not least, consumers' right on accurate information should also be considered, even in the case of products from the “grey market”. Moreover, obtained results present a valuable input into a food composition database.

4 Conclusion

Overall, presented results confirm previously drown conclusion that ethanol is by far the most important health concerning volatile compound in fruit spirits. Besides ethanol, methanol poses a high health risk, independently of the drinking pattern, when it comes to unrecorded spirits, and acetaldehyde considering the recorded ones. Both unrecorded and recorded spirits posed, to some extent, higher risk for men than for women, driven by higher alcohol consumption by men. Considering the type of spirit, tendency for lower MOEs for methanol, ethyl acetate and higher alcohols was observed in unrecorded spirits versus the recorded ones, whereby for acetaldehyde the opposite trend was noticed.

Although the most effective risk reduction measure would be reducing alcohol consumption per se (Lachenmeier et al., 2019), additional efforts should be focused on the establishment of the legal maximum limits for substances of interest, as well as on the broad coverage of the home-made products by quality checks, even if intended only for personal consumption. Relevant national authorities should be aware of the large quantities of unrecorded spirits sold on unofficial market and undertake appropriate measures.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Mr. Nebojsa Salaj for collecting part of the samples and processing the experimental data.

Funding

This study was funded by the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research, AP Vojvodina, grant number 142-451-2550/2021-01 (project “Herbal products - the potential of unused resources of AP Vojvodina for the development of new drugs and dietary products”).

References

- Can be the health risk from consumption of unrecorded fruit spirits containing alcohols other than ethanol ruled out? Regul. Toxicol. Pharm.. 2019;107:104431

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there any difference between the health risk from consumption of recorded and unrecorded spirits containing alcohols other than ethanol? a population-based comparative risk assessment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm.. 2019;106:334-345.

- [Google Scholar]

- CORDIS, 2013. European commission CORDIS EU Research Results . Final report summary: alcohol measures for public health research alliance (AMPHORA) Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2013. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/223059/reporting.

- Impacts of changes in alcohol consumption patterns during the first 2020 COVID-19 restrictions for people with and without mental health and neurodevelopmental conditions: a cross sectional study in 13 countries. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2022;101:103563

- [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, 2012. Guidance on selected default values to be used by the EFSA Scientific Committee, Scientific Panels and Units in the absence of actual measured data. EFSA journal. 10

- Ethyl Acetate. In: Wexler P., ed. Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Third Edition). Oxford: Academic Press; 2014. p. :506-510.

- [Google Scholar]

- EU, 2019. REGULATION (EU) 2019/787 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019R0787.

- FDA, 2021. FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION department of health and human services. Food for human consumption. Secondary direct food additives permitted in food for human consumption, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=173.228&SearchTerm=ethyl%20acetate.

- Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392:1015-1035.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223-1249.

- [Google Scholar]

- IARC, 1988. Alcohol Drinking, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 44.

- IARC, 1999. IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. List of Classifications. Agents classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–130.

- IARC, 2012. IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. List of Classifications. Agents classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–130.

- IARD, 2015. International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. AMPHORA chemical testing limits. http://iardunrecordedtoolkit.org/amphora_testing_limits.

- ICH, 1994. International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology Q2(R1).

- IHME, 2021. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2017. GBD Compare Data Visualisation. IHME, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 2019. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

- Carcinogenic, ethanol, acetaldehyde and noncarcinogenic higher alcohols, esters, and methanol compounds found in traditional alcoholic beverages. a risk assessment approach. Toxicol. Rep.. 2020;7:1057-1065.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defining maximum levels of higher alcohols in alcoholic beverages and surrogate alcohol products. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2008;50:313-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative risk assessment of carcinogens in alcoholic beverages using the margin of exposure approach. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131:E995-E1003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surrogate alcohol: what do we know and where do we go? Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res.. 2007;31:1613-1624.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exaggeration of health risk of congener alcohols in unrecorded alcohol: does this mislead alcohol policy efforts? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2019;107:104432

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of exposure to a country liquor (Toddy) during gestation on lipid metabolism in rats. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr.. 2001;56:133-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- A state-of-the-art review of the chemical composition of sugarcane spirits and current advances in quality control. J. Food Compos. Anal.. 2022;106:104338

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview of formation and roles of acetaldehyde in winemaking with emphasis on microbiological implications. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2000;35:49-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- J. Manthey et al., 2021. Use of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and other substances during the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Europe: a survey on 36,000 European substance users. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 16, 36

- Ethyl Acetate*. In: Wexler P., ed. Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Second Edition). New York: Elsevier; 2005. p. :277-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxic compounds in homemade spirits in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a pilot study. Bull. Chem. Technol. Bosnia Herzegovina. 2019;53:23-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methanol in unrecorded fruit spirits. does it pose a health risk to consumers in the European Union?. a probabilistic toxicological approach. Toxicol. Lett.. 2022;357:43-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- OEHHA, 2012. The Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. The Proposition 65 list. https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/methanol-fact-sheet.

- 1 - the threat to quality of alcoholic beverages by unrecorded consumption. In: Grumezescu A.M., Holban A.M., eds. Alcoholic Beverages. Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. :1-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- P.0014 Alcohol use, anger, aggression, resilience, and family support during the Covid-19 lockdown in Greece. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.. 2021;53:S11-S12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defining a tolerable concentration of methanol in alcoholic drinks. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.. 2001;20:563-568.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. Addiction. 2014;109:880-893.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acetaldehyde exposure underlies functional defects in monocytes induced by excessive alcohol consumption. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:13690.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health risk assessment for pediatric population associated with ethanol and selected residual solvents in herbal based products. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm.. 2019;107

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2018. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103981.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1