Photovoltaic response promoted via intramolecular charge transfer in pyrazoline-based small molecular acceptors: Efficient organic solar cells

⁎Corresponding authors. khalid@iq.usp.br (Muhammad Khalid), suvash_ojha@swmu.edu.cn (Suvash Chandra Ojha)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Herein, a series of pyrazoline based non-fullerene compounds (THP1-THP8) having ladder-like backbone was designed by structural modulation with various electron accepting moieties. The density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent functional theory (TD-DFT) study was executed at M06/6-311G(d,p) level for structural optimization and to determine the electronic and optical characteristics of the pyrazoline based chromophores. The optimized structures were employed to execute frontier molecular orbital (FMO), transition density matrix (TDM), density of state (DOS), open circuit voltage (Voc) and reorganization energy analyses at the aforementioned level of DFT to comprehend the photovoltaic (PV) response of THP1-THP8. The red-shifted absorption spectrum (512.861–584.555 nm) with reduced band gap (2.507–2.881 eV) allow considerable charge transferal from HOMO to LUMO in all the studied compounds. Global reactivity parameters (GRPs) demonstrated high softness with considerable reactivity in THP1-THP8. Moreover, remarkable Voc values (2.083–2.973 V) were noted for all the derivatives (THP1-THP8). However, THP2 with lowest energy gap (2.364 eV), highest λmax (617.482 nm) and softness (0.423 eV) values is considered good candidate among afore-said chromophores. Hence, the studied chromophores with efficient properties are appropriate for experimentalists in terms of manufacturing of efficient OSCs.

Keywords

Pyrazoline-based molecules

DFT

Optical properties

TDM

Open circuit voltage

1 Introduction

Development in science and technology offers advanced methods to produce clean energy at an adaptable level (Wu et al., 2005). The scientific community of the contemporary world is directing its approach of energy generation from greenhouse gas emission technologies to eco-friendly power generation projects and photovoltaic energy is a pertinent alternate for this aim (Shafiq et al., 2023b; ul Ain et al., 2021). The most auspicious approach of transforming solar energy into electrical power is by using photovoltaic cells employing photoelectric effect (Khalid et al., 2022a). Photovoltaic technology has been industrialized in the existing decades however, it still needs to be upgraded to attain the utmost output (Yaqoob et al., 2021). Usually, 173,000 terawatts of solar energy is received by the earth’s surface which is 10,000 times greater than the overall energy consumption (Aboulouard et al., 2021). The energy generated by PV cells epitomizes around 1% of the total energy requirement. It turns out that the required electrical power can be domestically produced by decreasing electrical deficits as well as storage capacities (Traverse et al., 2017).

Based on the material and techniques utilized to engineer solar cells, the PV cells are categorized into three generations. Initially, silicon based first-generation solar cells were developed and these cells were used for a long duration due to their stability, heat constancy and high efficiency. Later on, second and third-generation thin-film PV cells were introduced to overcome the deficiencies of crystalline silicon photovoltaics i.e., high cost of production and problematic installation on large scale (Conibeer et al., 2008; Green, 2004; Heidarzadeh and Tavousi, 2019). Over the last 15 years, apparent improvements in ‘second generation’ thin-film cells have been made. With the use of thin film, the cost of the material has been reduced by eradicating silicon. Furthermore, power conversion efficiency (PCE) has been significantly improved. With the passage of time as technology advanced, the manufacturing cost has dominated over the cost of material (Green, 2002). Thus, further progress of thin-film photovoltaics (PVs) confronted bottlenecks and the research on third-generation PVs has been progressed. These cells do not contain p-n junction as in conventional solar cells (Arjunan and Senthil, 2013) and are suitable for large-scale installation of PVs (Conibeer, 2007). Third-generation PV cells include polymer, organic PVs, (Yan and Saunders, 2014) hot carrier solar cells, (Tavousi, 2019) multi-junction cells (Conibeer, 2007) etc.

A keen examination reveals that OSCs have the potential to be engineered at less cost, effective using simple synthetic route with lightweight and high flexibility (Chen et al., 2011; Mahmood et al., 2018; Zhan and Marder, 2019). Besides, the OSCs exhibit irregular absorption that can be supervised to transmit visible, infrared and ultraviolet light simultaneously (Aboulouard et al., 2021). The active layer in OSCs generally comprises a blend of electron acceptor and donor with a bulk heterojunction (BHJ) structure that facilitates charge separation and transfer of hole and electron to their respective electrodes (Zhan and Marder, 2019). During the last two decades, fullerene derivatives remained the most extensively used acceptors in OSCs as they embrace fascinating assets comprising high PCE and exclusive electron and hole mobility (Yu et al., 1995). However, their morphological instability and confined variability of optoelectronic properties limit the viable progress of this field, particularly restraining the upper attainable device efficacies (Zhan and Marder, 2019). Organic fullerene-free acceptors offer the probability to overcome these limitations. Less toxicity, facile synthesis, lower level of highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and fine absorption spectrum made non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) progress a mainstream of today’s research (Chan et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018). Moreover, NFAs having acceptor–donor-acceptor (A-D-A) backbone presented around 17% PCE (Lin et al., 2019). They substantially enrich the carrier mobility with high intramolecular charge transfer rate within a molecule (Firdaus et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019).

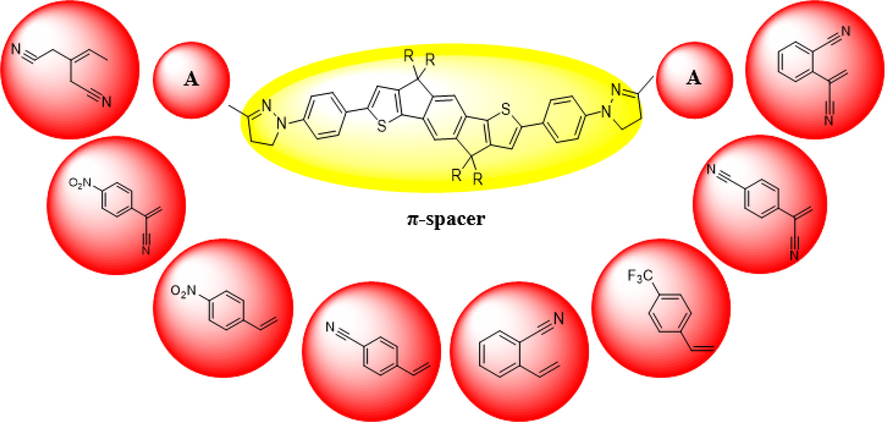

End-group modulation is viewed as an effective approach to modulate the optoelectronic behavior of materials utilized in PV devices (Khan et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2020). Herein, keeping in view the crystallinity and remarkable PCE of indacenodithiophene (IDT) (Arshad et al., 2022), we utilized it as π-spacer and enlarged π-conjugation with 1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole. The THP1 derivative is developed by attaching 3-ethylidenepentanedinitrile as end-capped acceptor moiety with π-spacer. The remaining chromophores (THP2-THP8) are designed by amending terminal acceptor entities (Szukalski et al., 2017). A comprehensive DFT study of designed derivatives (THP1-THP8) is performed with the characterization of essential parameters like the frontier molecular orbital (FMO), density of state (DOS), global reactivity parameters (GRPs), transition density matrix (TDM), reorganization energy and open circuit voltage (Voc) to explore the PV response of afore-said compounds. It is estimated that these innovative NFAs would play an indispensable role in the engineering of highly proficient OSCs.

2 Computational study

In the current investigation, non-fullerene electron acceptors having ladder-like backbone were designed by structural modulation of several end-capped acceptors. Gaussian 09 program package (Frisch et al., 2009) was utilized to compute the entire theoretical calculations of the studied chromophores (THP1-THP8). The optimization of THP1-THP8 was accomplished by using Minnesota 06 (M06) (Bryantsev et al., 2009) exchange-correlational functional along with 6-311G(d,p) (Andersson and Uvdal, 2005) basis set. Furthermore, to visualize the photovoltaic and optoelectronic properties, FMO, GRPs, DOS, Voc, UV–Vis absorption and TDM analyses were accomplished at the TD-DFT/M06/6-311G(d,p) level. A number of software i.e., Avogadro, (Hanwell et al., 2012) Gaussum, (O’boyle et al., 2008) Chemcraft, (Zhurko and Zhurko, 2009) PyMOlyze 2.0, (UrRehman et al., 2022) Multiwfn 3.7 (Lu and Chen, 2012) and Gauss view 6.0 (Dennington et al., 2016) were utilized to elucidate the results from output files.

Usually, reorganization energy is utilized to study the rate of charge transference and is segregated into two main types i.e., internal reorganization energy (λint) and external reorganization energies (λext). λint is concerned with the quick variations in internal composition, while λext is directly linked with the external environmental relaxation (Janjua, 2012; Khalid et al., 2020b). In this work, λext effect was neglected because of the little contribution of external environmental factors, so λint was considered. Hence, the reorganization energy of hole (λh) and electron (λe) can be computed with the aid of Eqs. (1) and (2) (Mehboob et al., 2021b).

3 Results and discussion

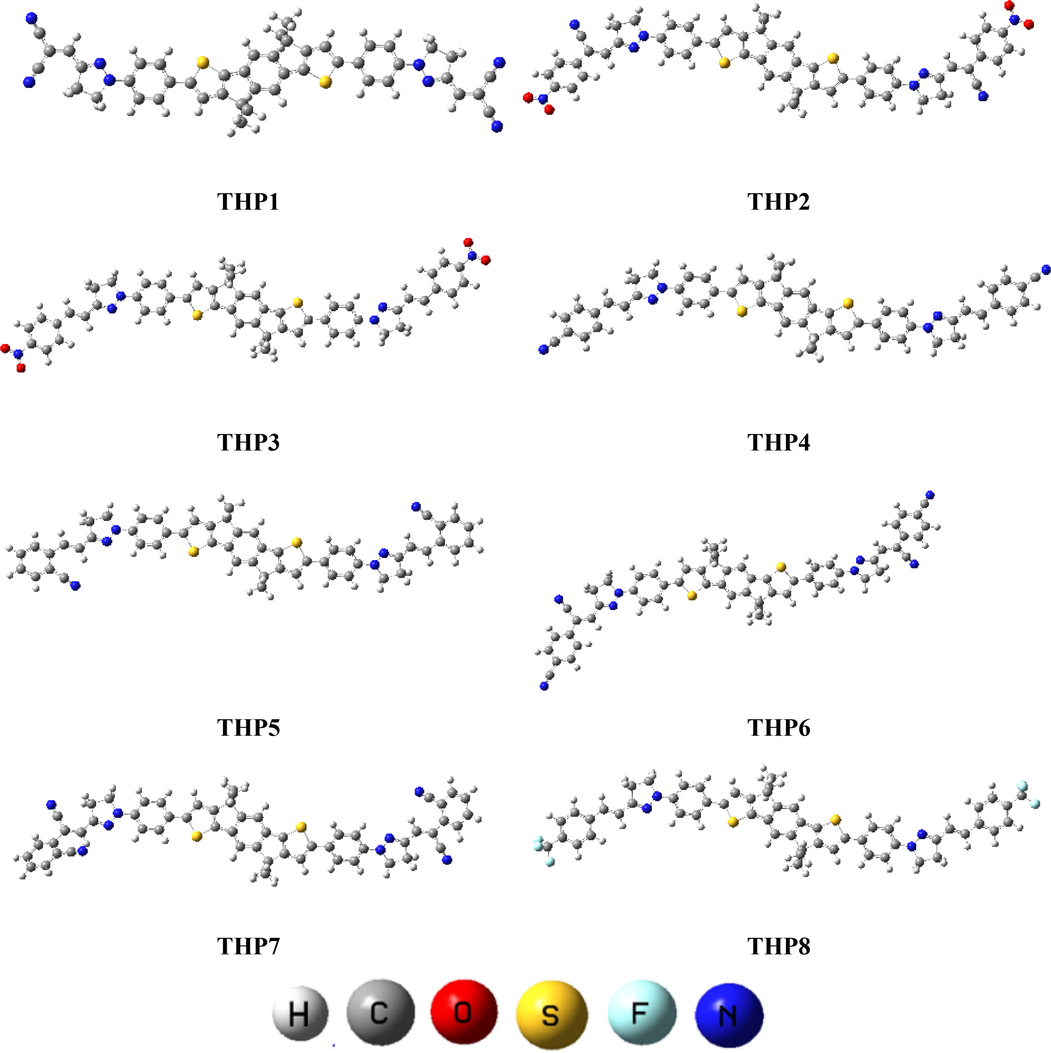

The present quantum chemical research envisages some effective NFAs having A-π-A framework with pyrazoline ring as a crucial component of each structure, are signified in Figure S1 and the optimized structures are illustrated in Fig. 2. In this report, eight novel molecules (Figure S1) are designed utilizing the end-capped modification approach to further discover the potential of IDT related compounds. The IUPAC names of compounds are given in Table S9 and structures of all the acceptors that are utilized in structural modulation are shown in Figure S2. Furthermore, their Cartesian coordinates are presented in Tables S1-S8. Literature survey discloses that acceptor groups are essential in tuning the absorption wavelength as well as energy gap of a compound (Khan et al., 2018). Thus, eight derivatives (THP1-THP8) are being designed by changing acceptor moieties to discover and enhance the electronic properties of OSCs. Moreover, to analyze how various acceptors affect the PV and spectral response, several parameters such as UV–Vis absorption wavelength, Voc and GRP have been computed by TD-DFT and DFT calculations. The schematic demonstration of THP1-THP8 are presented in Fig. 1.

- Schematic illustration of the designed compounds.

- Optimized structures of all the theoretically computed molecules (THP1-THP8).

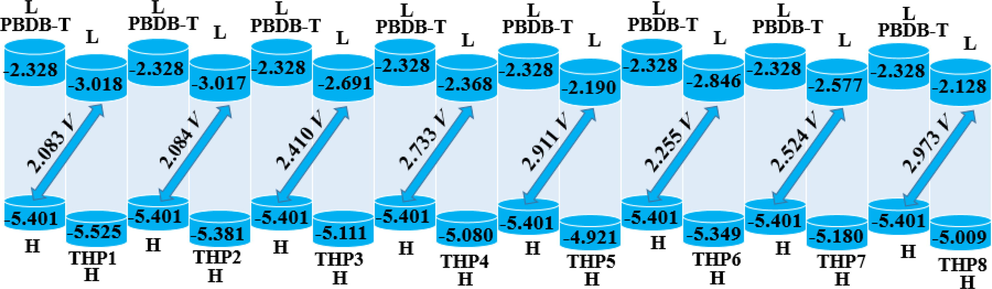

3.1 Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis

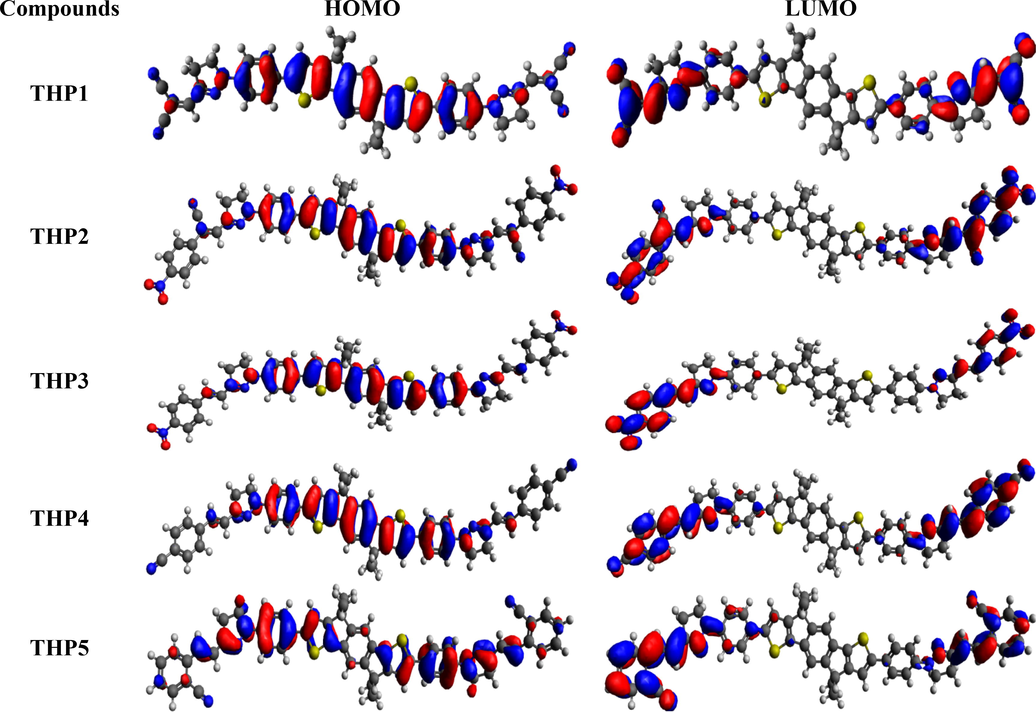

FMO analysis is an effective approach for exploring the optoelectronic characteristics and chemical stability of the molecule (Javed et al., 2014). The mechanical modeling and absorption spectrum are greatly influenced by FMOs i.e., HOMO and LUMO considered as valence and conduction bands, respectively (Mandado et al., 2006). This analysis unveils the electronic distribution pattern and also provide information about the properties of PVs having the capability to accelerate the transmission of electric current (Khan et al., 2019c; Peng and Yu, 1994). The energy gap among FMOs (

| Compounds | HOMO | LUMO | Egap |

|---|---|---|---|

| THP1 | −5.525 | −3.018 | 2.507 |

| THP2 | −5.381 | −3.017 | 2.364 |

| THP3 | −5.111 | −2.691 | 2.420 |

| THP4 | −5.080 | −2.368 | 2.712 |

| THP5 | −4.921 | −2.190 | 2.731 |

| THP6 | −5.349 | −2.846 | 2.503 |

| THP7 | −5.180 | −2.577 | 2.603 |

| THP8 | −5.009 | −2.128 | 2.881 |

Units in eV.

- The FMOs (HOMO and LUMO) of THP1-THP8.

- The FMOs (HOMO and LUMO) of THP1-THP8.

From literature, it has been noticed that experimentally determined HOMO/LUMO values (-5.63/-3.86 eV) of IDIC-C8 compound (Zhang et al., 2020) shows harmonization with the DFT computed results of our designed chromophores. The theoretically calculated EHOMO values of THP1-THP8 are −5.525, −5.381, −5.111, −5.080, −4.921, −5.349–5.180 and −5.009 eV, correspondingly while their ELUMO values are −3.018, −3.017, −2.691, −2.368, −2.190, −2.846, −2.577 and −2.128 eV, respectively. The Egap of THP1-THP8 is observed as 2.507, 2.364, 2.420, 2.712, 2.731, 2.503, 2.603 and 2.881 eV, respectively. The maximum value of Egap is noticed in THP8 (having three fluoro groups at terminal acceptor) i.e., 2.881 eV which is the uppermost value among all the derivatives (THP1-THP8). The fluorine substituents have lowest electron withdrawing capability than nitro and cyano groups utilized in other chromophores which resulted in superior Egap of THP8. The Egap value is declined to 2.712 and 2.731 eV in THP4 and THP5, respectively owing to the cyano group at para and ortho positions of peripheral acceptor unit (2-vinylbenzonitrile). In THP7 and THP6, the Egap is further dropped to 2.603 and 2.503 eV due to the 2-(1-cyanovinyl)benzonitrile and 4-(1-cyanovinyl) benzonitrile end-capped groups. Moreover, the Egap of 2.507 eV is noticed in THP1 that might be due to the existence of two cyano groups at the terminal acceptors. The greater electronegativity of cyano groups increases the acceptors capability to pull the electrons towards itself, results in reduced Egap among orbitals. Remarkably, the HOMO and LUMO energy difference is lowered to 2.420 eV in THP3 due to the presence of sole nitro group which has greater electron withdrawing capability. Moreover, the smallest value (2.364 eV) of Egap is viewed in THP2 owing to the nitro group which has strong electron withdrawing (-I) nature that attracts the electron density towards itself. Further, the presence of cyano group in the vicinity of benzene ring also abridged the Egap. Moreover, the overall decreasing trend of Egap is as follows: THP8 > THP5 > THP4 > THP7 > THP1 > THP6 > THP3 > THP2. The effective charge mobility and lowest Egap between orbitals is inspected in THP2 than all the examined chromophore that emerged as a competent PV-material.

The scheme of electronic charge distribution over the surface areas of THP1-THP8 is illustrated in Fig. 3. The electronic cloud is majorly occupied on π-spacer in HOMO, while in LUMO it is mainly concentrated on over terminal acceptors and minutely over π-spacer. This designates that substantial assistance of charge transmission from π-spacer towards acceptors is monitored in all the designed compounds (THP1-THP8).

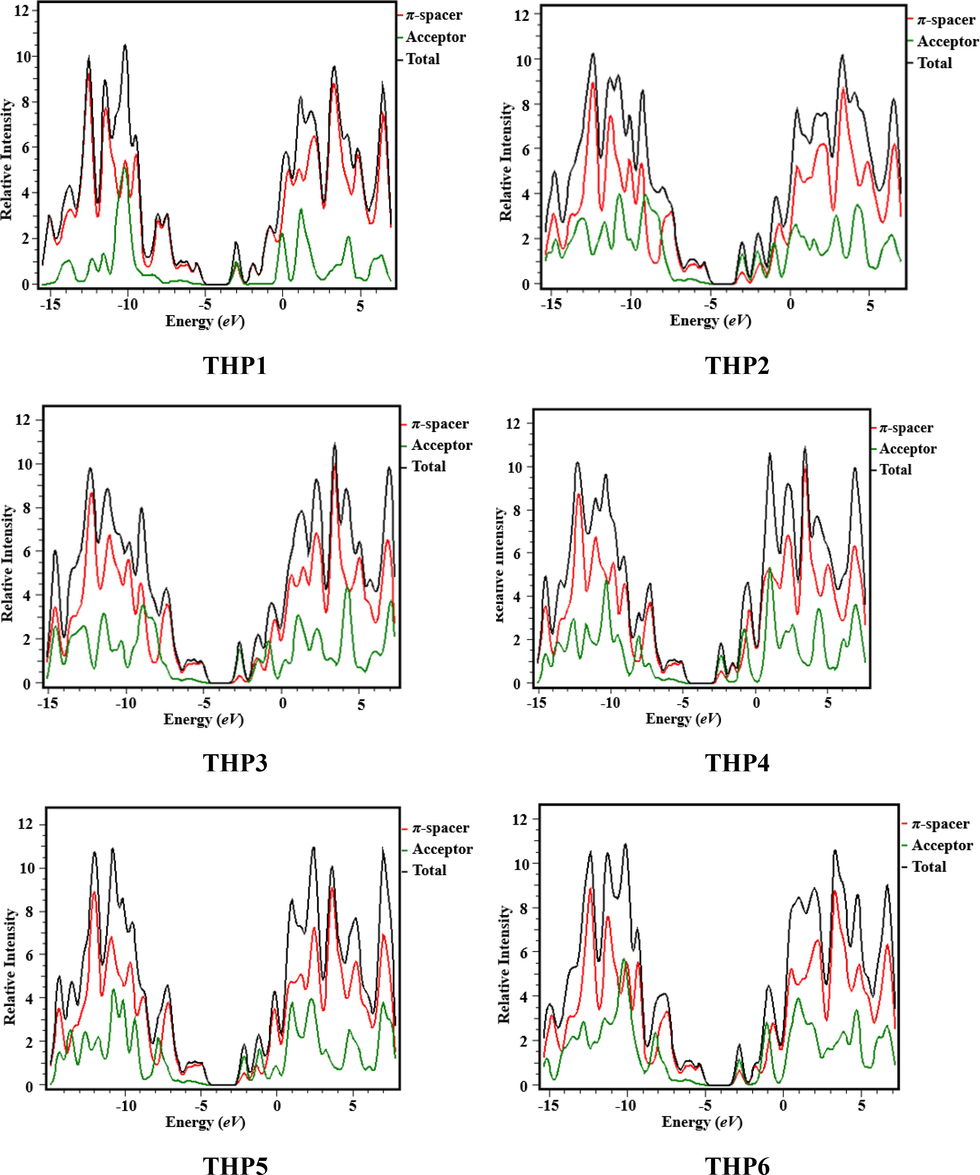

3.2 Density of state (DOS)

The DOS investigation was performed at M06 functional with 6-311G basis set to interpret the findings of THP1-THP7. To envisage the path of charge transmission, we separated our investigated chromophores into two fragments i.e., acceptor and π-spacer that are portrayed by green and red lines, correspondingly as shown in Fig. 4. The DOS study has been executed to ascertain the valuable contribution of every fragment over the molecular system which has particular number of electronic states (Adeel et al., 2021). It has unveiled the charge dissemination from HOMO which has large capacity to donate electrons to LUMO that has tendency to accept electrons (Goszczycki et al., 2017). The pattern of charge dissemination is changed by varying acceptor units that is supported by HOMO/LUMO percentage of DOS (Table S11). Herein, acceptor demonstrates the contribution of electronic charges as: 4.5, 5.5, 5.0, 5.1, 5.0, 5.6, 5.1 and 5.0% to HOMO, while 52.2, 70.4, 81.7, 68.2, 69.2, 62.4, 60.2 and 61.2% to LUMO for THP1-THP8, correspondingly. Similarly, π-spacer reveals the distribution of charges as: 95.5, 94.5, 95.0, 94.9, 95.0, 94.4, 94.9 and 95.0% to HOMO, whereas 47.8, 29.6, 18.3, 31.8, 30.7, 37.6, 39.8 and 38.8% to LUMO for THP1-THP8, respectively. In DOS graphs, the negative values denote the HOMO, whereas the positive values show LUMO along x-axis and the Egap expresses the distance among HOMOs and LUMOs (Khalid et al., 2022c). From DOS spectrum, it is anticipated that maximum charge density of HOMO is positioned over π-spacer at approximately −13 eV whereas LUMO is mainly resided over acceptor with highest peak at 3.5 eV in the aforesaid compounds. Overall, DOS analysis exhibits extensive charge transfer from π-bridge towards peripheral acceptor moieties in all the studied chromophores.

- Graphical illustration of DOS of the titled compounds (THP1-THP8).

- Graphical illustration of DOS of the titled compounds (THP1-THP8).

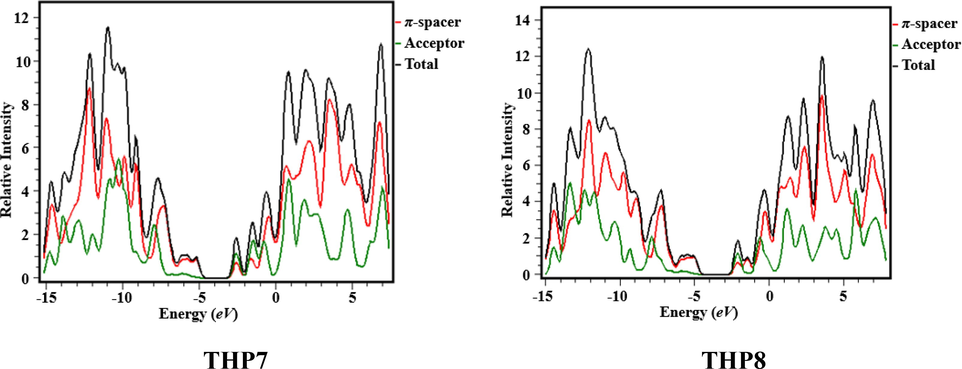

3.3 Optical response

TD-DFT computations are utilized to investigate the absorption spectrum of the titled chromophores (THP1-THP8) in gas phase at M06 with 6-311G(d,p) basis set. UV–Vis analysis gives substantial information about the nature of electronic transitions, possibility of charge transference as well as contributing configuration of the molecule. The oscillator strength (fos), maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax) and excitation energies (E) of lowest six singlet–singlet electronic transitions were examined and the outcomes are tabulated in Tables S13-S20, whereas some main results are depicted in Table S12. The optical absorption spectra of THP1-THP8 are exhibited in Fig. 5 in gaseous phase. The electronic excitation spectrum of the examined compounds is envisioned to acknowledge the influence of several acceptors on the spectral properties.

- Absorption spectra of entitled compounds THP1-THP8.

The results mentioned in Table S12 has disclosed that all the studied molecules display absorption in the visible region. The simulated λmax of THP1-THP8 are found in the range of 512.861––584.555 nm with oscillation strength of 1.807–2.951 and excitation energy of 2.008–2.417 eV in gaseous phase. The compound (THP2) depicted highest λmax value of 617.482 nm with transition energy value of 2.008 eV and 1.948 oscillation strength presenting 93% molecular orbital (MO) contribution from HOMO to LUMO. The utmost value of λmax in THP2 is ascribed to the extensively electron accepting nitro and cyano groups. The λmax in THP3 is abridged to 589.166 nm owing to 1-nitro-4-vinylbenzene group. In addition, in THP6, the λmax value is observed as 588.021 nm that is larger than THP1 and THP7 (584.555 and 567.096 nm, respectively). Furthermore, this value is squeezed to 539.202 and 537.123 nm in THP4 and THP5 due to the incorporation of cyano groups at the end-capped acceptors. The computed maximum wavelength for THP8 is observed at 512.861 nm with transition energy 2.417 eV and oscillation strength as 2.951 which is the lowermost value among all the studied compounds. The values of λmax are noticed in the subsequent declining trend as: THP2 > THP3 > THP6 > THP1 > THP7 > THP4 > THP5 > THP8. Lower excitation energy and increase in wavelength disclose that THP1-THP8 molecules exhibit greater charge transfer aptitude, consequently easy transition might occur amongst HOMO and LUMO. In a nutshell, THP2 possess highest λmax, least energy gap and minimum transition energy among all the derivatives which might be anticipated as a suitable material for OSCs.

3.4 Global reactivity parameters (GRPs)

The energy gap of HOMO and LUMO is utilized to compute the GRPs (Khalid et al., 2020a) of the entitled compounds (THP1-THP8) which in turn determine their reactivity as well as stability. Therefore, Egap is a dynamic feature to evaluate the GRPs such as electron affinity (EA), electronegativity (X), ionization potential (IP), softness (σ), electrophilicity index (ω), hardness (η) and chemical potential (μ) (Sheela et al., 2014). The ionization potential (IP = -EHOMO) and electron affinity (EA = -ELUMO) are calculated utilizing the given formulas (Pearson, 1986). Koopman’s theorem (Koopmans, 1934) is used to calculate the electronegativity [X = (IP + EA)/2], chemical hardness [η = (IP – EA)/2] and chemical potential [μ = EHOMO + ELUMO)/2]. Parr et al. (Parr et al., 1978) described the global electrophilicity index that is computed via using the given equation (ω = μ2/2η) (Chattaraj and Roy, 2007). Moreover, the global softness is determined by the mentioned equation (σ = 1/2η) (Koopmans, 1934). The values of η helps in determining the chemical reactivity and stability, (Pearson, 2005) while μ describes the electronic movement within the molecule (Toro-Labbé, 1999). Further, ω aids in determining the stability of a molecule when an additional electronic charge is acquired by it from an external source (Parr et al., 1999).

Table 2 elucidates the outcomes of GRPs for THP1-THP8 which are discussed here. The IP and EA designates the donating and accepting ability of a specie and are identical to the potential needed to transmit an electron from HOMO to LUMO. The polarization of a molecule is in direct relation with the EA and IP, which discloses the reactivity of a molecule. THP1-THP8 exhibit the high IP values (5.009–5.525 eV) and low EA values (2.128–3.018 eV) as mentioned in Table 2. All the studied molecules manifest comparable EA values which endorse their accepting nature. This might be owing to the existence of vigorous acceptors at the terminal portions of molecules. The values of X and ω also upholds the abovementioned statement. The chemical potential, global softness and hardness are correlated with the Egap and also give information about the reactivity. Thus, a compound with less Egap is considered as highly reactivity, soft and less stable. However, the compound with high Egap is assessed to be least reactive, hard and more kinetically stable.(Tahir et al., 2017) The increasing order of softness is: THP8 < THP5 < THP4 < THP7 < THP1 < THP6 < THP3 < THP2 with values as: 0.347 < 0.3662 < 0.3687 < 0.384 < 0.398 < 0.400 < 0.413 < 0.423 eV. Interestingly, THP2 exhibit the highest softness value that made it more polarized as well as reactive chromophore which might holds probable PV aptitude.

| Compounds | IP | EA | X | η | μ | ω | σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THP1 | 5.525 | 3.018 | 4.271 | 1.253 | −4.271 | 7.277 | 0.398 |

| THP2 | 5.381 | 3.017 | 4.199 | 1.182 | −4.199 | 7.458 | 0.423 |

| THP3 | 5.111 | 2.691 | 3.901 | 1.210 | −3.901 | 6.288 | 0.413 |

| THP4 | 5.080 | 2.368 | 3.724 | 1.356 | −3.724 | 5.113 | 0.368 |

| THP5 | 4.921 | 2.190 | 3.555 | 1.365 | −3.555 | 4.629 | 0.366 |

| THP6 | 5.349 | 2.846 | 4.097 | 1.251 | −4.097 | 6.708 | 0.400 |

| THP7 | 5.180 | 2.577 | 3.878 | 1.301 | −3.878 | 5.779 | 0.384 |

| THP8 | 5.009 | 2.128 | 3.568 | 1.440 | −3.568 | 4.420 | 0.347 |

3.5 Reorganization energy

Reorganization energy (λ) analysis is another essential tool utilized to disclose the performance and working of OSCs. Generally, λ is inversely correlated with the charge mobilities (hole and electron) (Köse et al., 2007). The lesser the reorganization energy, the greater will be the carrier mobility of a molecule. Reorganization energy is fluctuated by altering particular conditions, but these variations majorly influenced by the cationic and anionic geometries. Anionic geometry epitomizes electron transferal from the donor substance, whereas cationic geometry denotes hole transmission from acceptor material (Afzal et al., 2020). Reorganization energy is characterized into λint and λext, but we preferably choose λint by neglecting λext. The values of λh and λe are computed using Eqs. (1) and (2) and the results are collected in Table 3.

| Compounds | λe | λh |

|---|---|---|

| THP1 | −0.0002 | 0.0006 |

| THP2 | −0.0005 | −0.000007 |

| THP3 | −0.0004 | −0.0002 |

| THP4 | −0.0004 | −0.0004 |

| THP5 | −0.0008 | −0.0003 |

| THP6 | −0.0007 | −0.0005 |

| THP7 | −0.0006 | −0.0002 |

| THP8 | −0.00004 | −0.0004 |

Units in eV.

From literature survey, it has been observed that Bary et al., reported A1-A5 compounds which showed λe values in the range of 0.0077–0.0007 eV while λh values was found in the range of 0.0403–0.0003 eV (Bary et al., 2021) that are somewhat comparable to our designed compounds. Likewise, Adnan et al., reported that λe and λh values of R and CS1-CS5 are found in the range of 0.0184–0.0104 eV and 0.0206–0.0163 eV, respectively (Adnan et al., 2021). Kayani et al., observed that compounds R and Rm1-Rm4 depicted λe of 0.2290–0.0038 eV whereas λh values are noticed in the range of 0.0108–0.0072 eV (Kayani et al., 2021). Furthermore, Mehboob et al., studied R and H1-H5 chromophores which showed λe and λh values in the range of 0.0088–0.0104 eV and 0.0090–0.0060 eV, correspondingly (Mehboob et al., 2021c). Siddique et al., reported that R and D1-D4 compounds depicted λe values in the range of 0.1915–0.1344 eV whereas λh values are noticed in the range of 0.0834–0.0629 eV (Siddique et al., 2020) which are overestimated than out entitled compounds. The computed values of electron motilities for THP1-THP8 are −0.0002, −0.0005, −0.0004, −0.0004, −0.0008, −0.0007, −0.0006, −0.00004 eV, respectively. Among all studied chromophores, THP5 depicted the lowest value of λe which shows greater electron transference rate between HOMO and LUMO. Likewise, THP6 and THP2 have significantly better charge mobilities due to their lesser λe values. The escalating order of λe for the all the entitled compounds is: THP5 < THP6 < THP2 < THP4 = THP3 < THP1 < THP8. Similarly, the theoretically computed λh values for THP1-THP8 are 0.0006, −0.000007, −0.0002, −0.0004, −0.0003, −0.0005, −0.0002, −0.0004 eV, correspondingly. The ascending order of λh for all the entitled compounds are: THP6 < THP4 = THP8 < THP5 < THP3 = THP7 < THP2 < THP1. This analysis disclosed that λe values of all the examined chromophores are observed lower than λh values except THP8. Overall, the reduction in terms of λe designates that all the chromophores are promising applicants for transferal of electrons and can be used as competent PV materials.

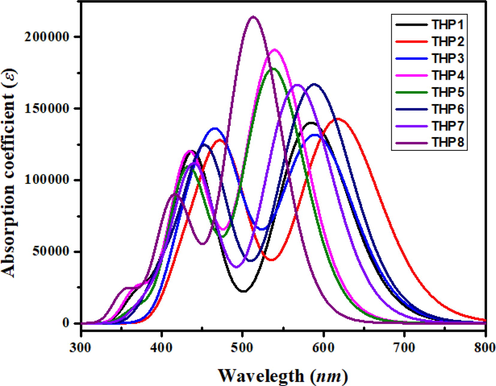

3.6 Open circuit voltage (Voc)

Open Circuit Voltage (Voc) is indispensable to elucidate the performance of OSCs and shows the maximum magnitude of voltage that can be taken out from any optically active material at zero current (Tang and Zhang, 2012). It plays an indispensable role to get insights into the working mechanics of organic semiconductor materials (Irfan et al., 2017). Numerous features influence the Voc i.e., light source, light intensity, temperature of OSCs, external environmental proficiency, charge carrier recombination and several other environmental factors (Saleem et al., 2021). Primarily, Voc is influenced by light generation and saturation voltage that helps in the recombination of PV devices. The Egap of donor and acceptor i.e., HOMOPBDB-T-LUMOacceptor is directly associated with the Voc. In the present quantum chemical calculations, PBDB-T donor molecule (Zheng et al., 2020) (which has EHOMO of −5.401 eV) is used to compute the Voc and the findings are summarized in Fig. 6. The calculated Voc outcomes of THP1-THP8 by using Eq. (3) developed by Scharber (Scharber et al., 2006) are grouped in Table 4.

- Diagrammatic representation of Voc of THP1-THP8 with PBDB-T.

| Compounds | VOC (V) |

|

|---|---|---|

| THP1 | 2.083 | 2.383 |

| THP2 | 2.084 | 2.384 |

| THP3 | 2.410 | 2.71 |

| THP4 | 2.733 | 3.033 |

| THP5 | 2.911 | 3.211 |

| THP6 | 2.255 | 2.555 |

| THP7 | 2.524 | 2.824 |

| THP8 | 2.973 | 3.273 |

The computed values of Voc of THP1-THP8 with regards to the energy gap of HOMOdonor –LUMOacceptor are examined to be 2.083, 2.084, 2.410, 2.733, 2.911, 2.255, 2.524 and 2.973 V, correspondingly. The Voc of the examined compounds are perceived to be in the subsequent declining order: THP8 > THP5 > THP4 > THP7 > THP3 > THP6 > THP2 > THP1. The highest value of Voc is noticed in THP8 at 2.973 V and this larger Voc value demonstrates the contribution to their superior LUMO values. Moreover, the Voc values majorly depends on the energy difference of a molecule that is an innate property of semiconductors. Having less energy gap means relaxed excitation and maximum photons would have greater energy than required for excitation producing more electricity with greater PV response and higher PCE. In this report, we made BHJ device by blending PBDB-T donor polymer with our designed acceptor molecules. When the complex developed, we observed that low level of LUMO of our acceptors enhance the transfer of charge carriers from HOMO of PBDB-T and thus escalate the transitions which results in higher efficiencies.

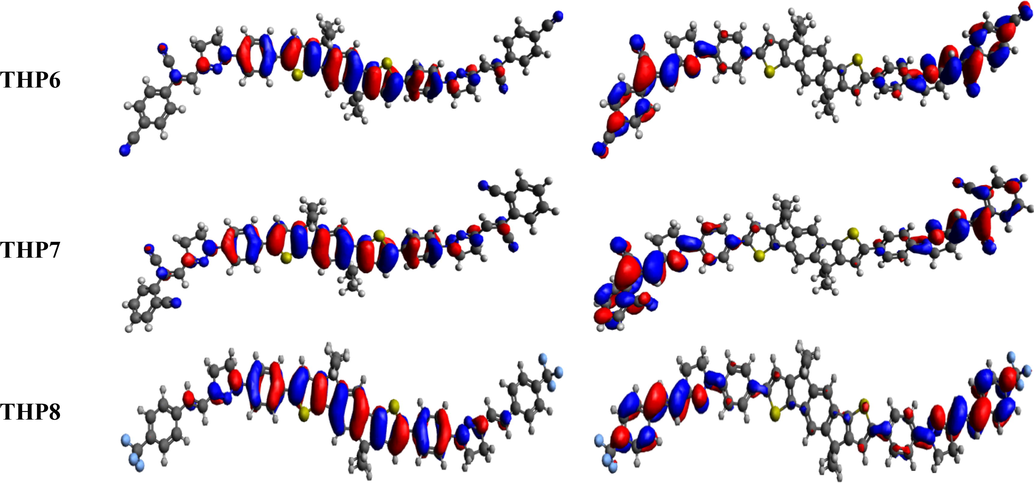

3.7 Transition density matrix (TDM)

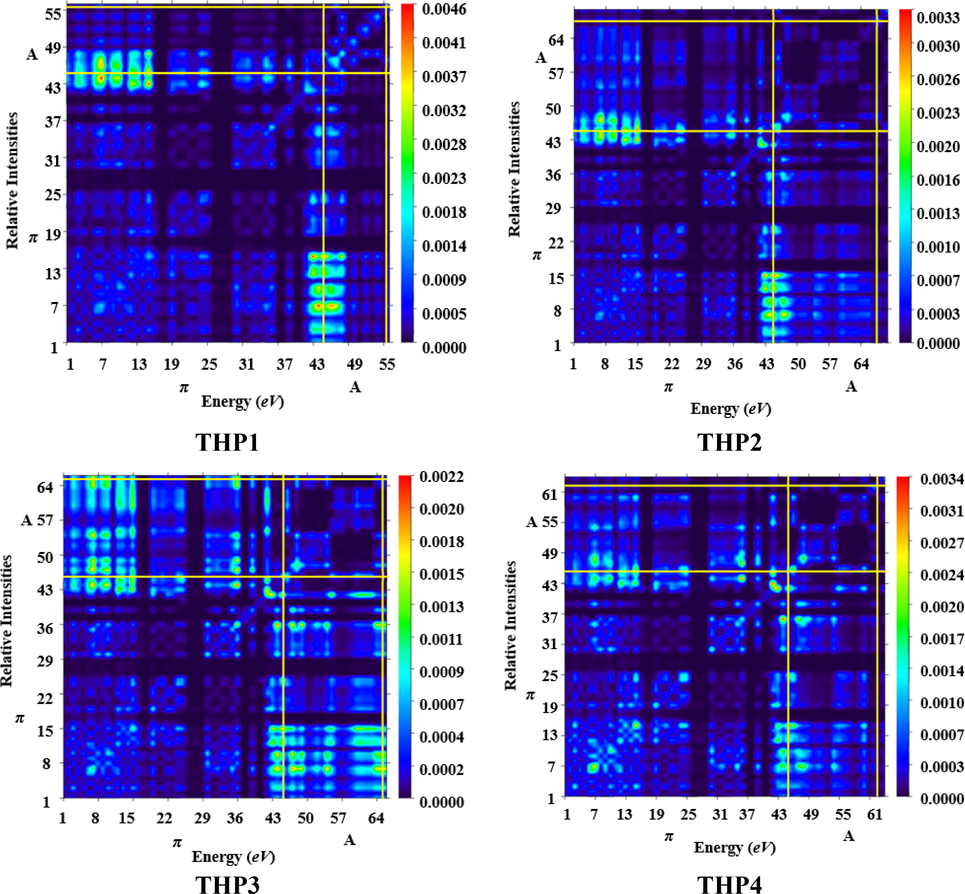

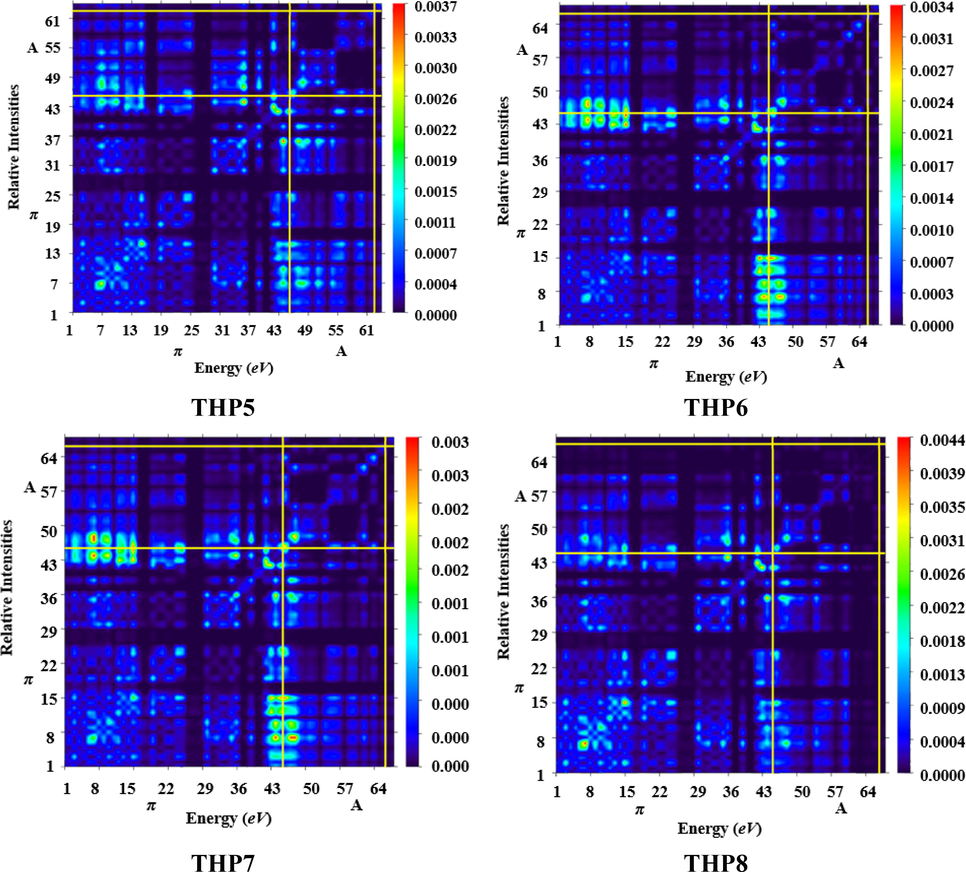

TDM analysis assists in interpreting the transition process, (Ans et al., 2019) electronic excitation state and hole-electron overlapping (Mehboob et al., 2021a). In addition, it is very valuable in evaluating the behavior of electronic transitions in the excited (S1) state, interaction among acceptor and donor entities accompanied by electron and hole localization as well as the extent of intramolecular charge transference (Ans et al., 2018). The determination of these parameters aids in evaluating the function of OSCs. M06 method in conjunction with 6-311G(d,p) basis set was used to ascertain the absorption and emission of all the designed chromophores (THP1-THP8). This analysis offers a 3D heat map with appropriate color discrepancy i.e., exhibited by blue region. The impact of hydrogen atoms has been overlooked due to their minute contribution in transition. The pictorial display of TDM analysis is given in Fig. 7.

- TDM graphs of the titled molecules (THP1-THP8).

- TDM graphs of the titled molecules (THP1-THP8).

In the current examination, we split our molecules (THP1-THP8) into two different portions i.e., acceptor and π-spacer. From FMO investigation, it is revealed that charge transmission is substantially executed over the molecule. The TDM pictographs disclosed that, there is an effective diagonal transmission of electron density from π-spacer towards terminal acceptors in all the chromophores, permitting good charge transference without any confinement. Moreover, electron hole pair generation and excitation of charge coherence also appear to proliferate non-diagonally over the TDM plots. Besides, calculation of TDM maps of THP1-THP8 indicate schematic, simpler and progressive exciton dissociation in the S1 state which proves valuable for future applications.

3.8 Exciton binding energy (Eb)

Binding energy (Eb) is another distinctive feature correlated to TDMs that is utilized to evaluate the PV response of OSCs. It is a significant parameter for the evaluation of exciton dissociation capability and columbic force of interaction among electron and hole. The Eb is in inverse relation to the exciton dissociation and directly associated with columbic interaction (Farhat et al., 2020; Khalid et al., 2022b). The Eb of THP1-THP8 is computed from the difference in Egap of LUMO-HOMO and optimization energy (Eopt) as shown by Eq. (4) (Köse, 2012).

In Eq. (4), EL-H indicates the energy difference among HOMO/LUMO and Eopt represents the lowest amount of energy necessary for excitation form S0 to S1 state, which generates an electron-hole pair (Janjua et al., 2012b; Khan et al., 2019a). The calculated outcomes of Eb are grouped in Table 5.

| Compounds | EH-L | Eopt | Eb |

|---|---|---|---|

| THP1 | 2.507 | 2.121 | 0.386 |

| THP2 | 2.364 | 2.008 | 0.356 |

| THP3 | 2.420 | 2.104 | 0.316 |

| THP4 | 2.712 | 2.299 | 0.413 |

| THP5 | 2.731 | 2.308 | 0.423 |

| THP6 | 2.503 | 2.109 | 0.394 |

| THP7 | 2.603 | 2.186 | 0.417 |

| THP8 | 2.881 | 2.417 | 0.464 |

The values of Eb for THP1-THP8 are calculated as 0.386, 0.356, 0.316, 0.413, 0.423, 0.394, 0.417 and 0.464 eV, correspondingly. THP3 gives the lowermost value (0.316 eV) of Eb exhibiting higher efficiency of charge dissociation in S1 state as compared to the other chromophores. Generally, the compounds having 1.9 eV or lesser Eb value are regarded as effective PV candidates with inspiring Voc. Remarkably, our titled molecules (THP1-THP8) has expressed lower values of Eb than 1.9 eV. The descending trend of Eb is: THP8 > THP5 > THP7 > THP4 > THP6 > THP1 > THP2 > THP3. So, THP3 molecule possessed lowest Eb elucidating greatest potential of charge separation with exceptional optical and electronic properties.

4 Conclusion

Conclusively, state-of-the-art quantum chemical procedures have been utilized to inspect the electronic and photophysical capabilities of eight pyrazoline-based NFAs (THP1-THP8), designed by altering terminal acceptor moieties. The structural tailoring has demonstrated as a significant strategy to acquire inspiring PV compounds with remarkable optoelectronic possessions for OSCs. FMO study depicted that least band gap of 2.364 eV is perceived in THP2, while for all the derivatives, Egap values fall in the following range of 2.507–2.881 eV with effective charge transference rate that is further endorsed by the DOS and TDM analyses. Furthermore, GRPs studies disclosed that extensive conjugation gives exceptional stability to the studied chromophores. Likewise, THP1-THP8 displayed red shifted absorption spectra at 512.861–584.555 nm range in gas phase. The Voc of THP1-THP8 with regards to HOMOPBDB-T-LUMOacceptor are observed with satisfactory values. The binding energy of the entitled chromophores (THP1-THP8) are found comparable with each other resulted in higher exciton dissociation. Furthermore, least reorganization energy in the above-mentioned chromophores for electron with hole is also examined. Amongst all the designed chromophores, THP2 owing to the strong electron accepting capability is recognized as a significant candidate for OSCs applications with outstanding PV properties comprising highest λmax (617.482 nm), lowest energy gap (2.364 eV) and highest softness (0.423 eV). Our outcomes indicated that incorporating electron-accepting groups is an effective strategy for designing promising NF based OSCs. The designed molecules specifically THP2 is suggested for production of high-performance OSCs devices.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Muhammad Khalid gratefully acknowledges the financial support of HEC Pakistan (project no. 20-14703/NRPU/R&D/HEC/2021). A. A.C.B. acknowledges the financial support of the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (Grants 2014/25770-6 and 2015/01491-3), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientı́fico e Tecnológico (CNPq) of Brazil for academic sup- port (Grant 309715/2017-2), and Coordenac¸ ão de Aperfeic¸ oa- mento de Pessoal de Nı́vel Superior – Brasil (CAPES) that partially supported this work (Finance Code 001). The authors thank the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2023R6), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. S.C.O. acknowledges the support from the doctoral research fund of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- New non-fullerene electron acceptors-based on quinoxaline derivatives for organic photovoltaic cells: DFT computational study. Synth. Met.. 2021;279:116846

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploration of CH⋯ F & CF⋯ H mediated supramolecular arrangements into fluorinated terphenyls and theoretical prediction of their third-order nonlinear optical response. RSC Adv.. 2021;11:7766-7778.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico designing of efficient C-shape non-fullerene acceptor molecules having quinoid structure with remarkable photovoltaic properties for high-performance organic solar cells. Optik. 2021;241:166839

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing indenothiophene-based acceptor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters for fullerene-free organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model.. 2020;26:1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical studies and spectroscopic characterization of novel 4-methyl-5-((5-phenyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-yl) thio) benzene-1, 2-diol. J. Mol. Struct.. 2016;1119:18-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- New scale factors for harmonic vibrational frequencies using the B3LYP density functional method with the triple-ζ basis set 6–311+ G (d, p) Chem. A Eur. J.. 2005;109:2937-2941.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing three-dimensional (3D) non-fullerene small molecule acceptors with efficient photovoltaic parameters. ChemistrySelect. 2018;3:12797-12804.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing indacenodithiophene based non-fullerene acceptors with a donor–acceptor combined bridge for organic solar cells. RSC Adv.. 2019;9:3605-3617.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploration of the intriguing photovoltaic behavior for fused indacenodithiophene-based A-D–A conjugated systems: a DFT model study. ACS Omega. 2022;7:11606-11617.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing small organic non-fullerene acceptor molecules with diflorobenzene or quinoline core and dithiophene donor moiety through density functional theory. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:19683.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of B3LYP, X3LYP, and M06-class density functionals for predicting the binding energies of neutral, protonated, and deprotonated water clusters. J. Chem. Theory Comput.. 2009;5:1016-1026.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood proteomic profiling in inherited (ATTRm) and acquired (ATTRwt) forms of transthyretin-associated cardiac amyloidosis. J. Proteome Res.. 2017;16:1659-1668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hierarchical nanomorphologies promote exciton dissociation in polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Nano Lett.. 2011;11:3707-3713.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silicon quantum dot nanostructures for tandem photovoltaic cells. Thin Solid Films. 2008;516:6748-6756.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R., Keith, T.A., Millam, J.M., 2016. GaussView 6.0. 16. Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA.

- Tuning the optoelectronic properties of Subphthalocyanine (SubPc) derivatives for photovoltaic applications. Opt. Mater.. 2020;107:110154

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-range exciton diffusion in molecular non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Commun.. 2020;11:5220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G.A., 2009. Gaussian 09, Revision D. 01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT. See also: URL: http://www.gaussian.com.

- Synthesis, crystal structures, and optical properties of the π-π interacting pyrrolo [2, 3-b] quinoxaline derivatives containing 2-thienyl substituent. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1146:337-346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Third generation photovoltaics: solar cells for 2020 and beyond. Physica E. 2002;14:65-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminf.. 2012;4:1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance enhancement methods of an ultra-thin silicon solar cell using different shapes of back grating and angle of incidence light. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2019;240:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design of donor–acceptor–donor (D–A–D) type small molecule donor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2017;117:e25363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum mechanical design of efficient second-order nonlinear optical materials based on heteroaromatic imido-substituted hexamolybdates: First theoretical framework of POM-based heterocyclic aromatic rings. Inorg. Chem.. 2012;51:11306-11314.

- [Google Scholar]

- A DFT study on the two-dimensional second-order nonlinear optical (NLO) response of terpyridine-substituted hexamolybdates: physical insight on 2D inorganic–organic hybrid functional materials. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2012;2012:705-711.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of π-conjugation spacer (CC) on the first hyperpolarizabilities of polymeric chain containing polyoxometalate cluster as a side-chain pendant: A DFT study. Comput. Theor. Chem.. 2012;994:34-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photophysical and electrochemical properties and temperature dependent geometrical isomerism in alkyl quinacridonediimines. New J. Chem.. 2014;38:752-761.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tris-isopropyl-sily-ethynyl anthracene based small molecules for organic solar cells with efficient photovoltaic parameters. Comput. Theor. Chem.. 2021;1202:113305

- [Google Scholar]

- First principles study of electronic and nonlinear optical properties of A-D–π–A and D–A–D–π–A configured compounds containing novel quinoline–carbazole derivatives. RSC Adv.. 2020;10:22273-22283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing 2D fused ring materials for small molecules organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem.. 2020;1183:112848

- [Google Scholar]

- First theoretical framework for highly efficient photovoltaic parameters by structural modification with benzothiophene-incorporated acceptors in dithiophene based chromophores. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12:20148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enriching NLO efficacy via designing non-fullerene molecules with the modification of acceptor moieties into ICIF2F: an emerging theoretical approach. RSC Adv.. 2022;12:13412-13427.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical designing of non-fullerene derived organic heterocyclic compounds with enhanced nonlinear optical amplitude: a DFT based prediction. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12:20220.

- [Google Scholar]

- First theoretical framework of triphenylamine–dicyanovinylene-based nonlinear optical dyes: structural modification of π-linkers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:4009-4018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of second-order nonlinear optical properties of D–π–A compounds containing novel fluorene derivatives: a promising route to giant hyperpolarizabilities. J. Clust. Sci.. 2019;30:415-430.

- [Google Scholar]

- First theoretical probe for efficient enhancement of nonlinear optical properties of quinacridone based compounds through various modifications. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2019;715:222-230.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing triazatruxene-based donor materials with promising photovoltaic parameters for organic solar cells. RSC Adv.. 2019;9:26402-26418.

- [Google Scholar]

- In silico modeling of new “Y-Series”-based near-infrared sensitive non-fullerene acceptors for efficient organic solar cells. ACS Omega. 2020;5:24125-24137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel W-shaped oxygen heterocycle-fused fluorene-based non-fullerene acceptors: first theoretical framework for designing environment-friendly organic solar cells. Energy Fuel. 2021;35:12436-12450.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular designing of high-performance 3D star-shaped electron acceptors containing a truxene core for nonfullerene organic solar cells. J. Phys. Org. Chem.. 2021;34:e4119.

- [Google Scholar]

- Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den einzelnen Elektronen eines Atoms. Physica. 1934;1:104-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of acceptor strength in thiophene coupled donor–acceptor chromophores for optimal design of organic photovoltaic materials. Chem. A Eur. J.. 2012;116:12503-12509.

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical studies on conjugated phenyl-cored thiophene dendrimers for photovoltaic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2007;129:14257-14270.

- [Google Scholar]

- 17% efficient organic solar cells based on liquid exfoliated WS2 as a replacement for PEDOT: PSS. Adv. Mater.. 2019;31:1902965.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem.. 2012;33:580-592.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent progress in porphyrin-based materials for organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6:16769-16797.

- [Google Scholar]

- On the applicability of QTAIM, Hirshfeld and Mulliken delocalisation indices as a measure of proton spin–spin coupling in aromatic compounds. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2006;430:454-458.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum chemical designing of banana-shaped acceptor materials with outstanding photovoltaic properties for high-performance non-fullerene organic solar cells. Synth. Met.. 2021;277:116800

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum chemical design of near-infrared sensitive fused ring electron acceptors containing selenophene as π-bridge for high-performance organic solar cells. J. Phys. Org. Chem.. 2021;34:e4204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing of benzodithiophene core-based small molecular acceptors for efficient non-fullerene organic solar cells. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2021;244:118873

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum chemical exploration of A- π1–D1–π2–D2-Type compounds for the exploration of chemical reactivity, optoelectronic, and third-order nonlinear optical properties. ACS Omega 2023

- [Google Scholar]

- Cclib: a library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem.. 2008;29:839-845.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electronegativity: the density functional viewpoint. J. Chem. Phys.. 1978;68:3801-3807.

- [Google Scholar]

- Absolute electronegativity and hardness correlated with molecular orbital theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 1986;83:8440-8441.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second-order nonlinear optical polyimide with high-temperature stability. Macromolecules. 1994;27:2638-2640.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing of small molecule non-fullerene acceptors with cyanobenzene core for photovoltaic application. Comput. Theor. Chem.. 2021;1197:113154

- [Google Scholar]

- Design rules for donors in bulk-heterojunction solar cells—Towards 10% energy-conversion efficiency. Adv. Mater.. 2006;18:789-794.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploration of photovoltaic behavior of benzodithiophene based non-fullerene chromophores: first theoretical framework for highly efficient photovoltaic parameters. J. Mater. Res. Technol.. 2023;24:1882-1896.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of structural modifications into benzodithiophene compounds on electronic and optical properties for organic solar cells. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2023;308:128154

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular orbital studies (hardness, chemical potential and electrophilicity), vibrational investigation and theoretical NBO analysis of 4–4′-(1H–1, 2, 4-triazol-1-yl methylene) dibenzonitrile based on abinitio and DFT methods. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2014;120:237-251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing triphenylamine-configured donor materials with promising photovoltaic properties for highly efficient organic solar cells. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:7358-7369.

- [Google Scholar]

- A low cost and high performance polymer donor material for polymer solar cells. Nat. Commun.. 2018;9:743.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical structure versus second-order nonlinear optical response of the push–pull type pyrazoline-based chromophores. RSC Adv.. 2017;7:9941-9947.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis, single crystal analysis, and computational studies of sulfanilamide derivatives. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1127:766-776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design of donors with broad absorption regions and suitable frontier molecular orbitals to match typical acceptors via substitution on oligo (thienylenevinylene) toward solar cells. J. Comput. Chem.. 2012;33:1353-1363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wavelength-division demultiplexer based on hetero-structure octagonal-shape photonic crystal ring resonators. Optik. 2019;179:1169-1179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of chemical reactions from the profiles of energy, chemical potential, and hardness. Chem. A Eur. J.. 1999;103:4398-4403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergence of highly transparent photovoltaics for distributed applications. Nat. Energy. 2017;2:849-860.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing of benzodithiophene acridine based Donor materials with favorable photovoltaic parameters for efficient organic solar cell. Comput. Theor. Chem.. 2021;1200:113238

- [Google Scholar]

- DFT analysis of different substitutions on optoelectronic properties of carbazole-based small acceptor materials for Organic Photovoltaics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process.. 2022;140:106381

- [Google Scholar]

- Silicon-based solar cell system with a hybrid PV module. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2005;87:637-645.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-junction polymer solar cells with 16.35% efficiency enabled by a platinum (II) complexation strategy. Adv. Mater.. 2019;31:1901872.

- [Google Scholar]

- Third-generation solar cells: a review and comparison of polymer: fullerene, hybrid polymer and perovskite solar cells. RSC Adv.. 2014;4:43286-43314.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, optical and photovoltaic properties of unfused Non-Fullerene acceptors for efficient solution processable organic solar cell (Estimated PCE greater than 12.4%): A DFT approach. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;341:117428

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymer photovoltaic cells: enhanced efficiencies via a network of internal donor-acceptor heterojunctions. Science. 1995;270:1789-1791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-fullerene acceptors inaugurating a new era of organic photovoltaic research and technology. Mater. Chem. Front.. 2019;3:180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuning molecular geometry and packing mode of non-fullerene acceptors by alternating bridge atoms towards efficient organic solar cells. Mater. Chem. Front.. 2020;4:2462-2471.

- [Google Scholar]

- PBDB-T and its derivatives: A family of polymer donors enables over 17% efficiency in organic photovoltaics. Mater. Today. 2020;35:115-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zhurko, G.A., Zhurko, D.A., 2009. ChemCraft, version 1.6. URL: http://www.chemcraftprog.com.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105271.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: