Translate this page into:

Structural modifications and biomedical applications of π-extended, π-fused, and non-fused tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives

⁎Corresponding authors. renubalu@sejong.ac.kr (Sri Renukadevi Balusamy), spark0920@kongju.ac.kr (Sri Renukadevi Balusamy), renubalu@sejong.ac.kr (Sanghyuk Park) spark0920@kongju.ac.kr (Sanghyuk Park)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

In this present study, we have designed, synthetized twenty three tetra-substituted-imidazole-based fluorescent dyes that belongs to three different families of π-extended, π-fused, and non-fused tetra-substituted derivatives, to investigate their photophysical and biological properties namely anti-cancer and urease inhibitory activity. The impact of structural variation on photophysical properties, and their association with solvent’s polarity, and proticity were throughly examined by comparing with their analogues of blocked ESIPT functionality. Further, they were studied experimentally by means of absorption and fluorescence spectra monitoring through different solvent systems as well as theoretically by density functional theory/time dependent-density functional theory (DFT/TDDFT) calculations, respectively. For the evaluation of biological properties of imidazole molecules, urease inhibitory activity of the imidazole derivatives against urease protein 4H9M was investigated through docking and in vitro studies. Among the synthesized compounds, AHPI-Br and POMPI-F showed the most effective urease inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 0.0288 ± 0.0034 and 0.0289 ± 0.0025 μM and provided the highest docking scores. Moreover, anti-cancer activity of PHPI-I and PHPI-CI imidazole derivatives was confirmed by cytotoxic, and flurorescene analysis in stomach cancer cell lines (AGS). Our results demonstrated that PHPI-I, PHPI-Cl exhibited significant apoptotic mediated cell death compared to all other imidazole groups in both in vitro and in silico analysis. Our present study concluded that synthesis of imidazole derivatives have ability to inhibit urease enzyme activity and anti-cancer activity in vitro and can act as a potential therapeutic targets and warrants in vivo studies.

Keywords

Imidazole molecules

ESIPT

DFT/TD-DFT

Urease inhibition

Anti-cancer

Molecular docking

- ESIPT

-

Excited-state intramolecular proton transfer

- DFT

-

Density functional theory

- K

-

Keto

- MeCN

-

Acetonitrile

- PL

-

Photoluminescence

- ICT

-

Intramolecular charge transfer

- SAR

-

Structure-activity relationship

- EI

-

Enzyme inhibitor

- ESI

-

Enzyme-substrate inhibitor

- TLC

-

Thin layer chromatography

- ATPI-F

-

7-(4-fluorophenyl)-8-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole

- AOMPI-F

-

7-(4-fluorophenyl)-8-(2-methoxyphenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole,

- AHPI

-

2-(7-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- AHPI-F

-

2-(7-(4-fluorophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- AHPI-Cl

-

2-(7-(4-chlorophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- AHPI-Br

-

2-(7-(4-bromophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- AHPI-I

-

2-(7-(4-iodophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- AHPI- EtOAc

-

4-(8-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-7-yl)phenethyl acetate

- AMHPI

-

4-methoxy-2-(7-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol

- BTPI-F

-

1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazole

- BOMPI-F

-

1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazole

- BHPI

-

2-(1,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- BHPI-F

-

2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- BHPI-Cl

-

2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- BHPI-Br

-

2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- BHPI-I

-

2-(1-(4-iodophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- PTPI-F

-

1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole

- POMPI-F

-

1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole

- PHPI

-

2-(1-phenyl-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- PHPI-F

-

2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- PHPI-Cl

-

2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- PHPI-Br

-

2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- PHPI-I

-

2-(1-(4-iodophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol

- OD

-

Optical density

- SCF-TD-DFT

-

Self Consistent Field-Time Dependent-DFT

- DMSO

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Substituted imidazole derivatives are one of the significant classes of heterocyclic scaffolds which plays an important core fragment of a wide range of natural products and biological system (Alghamdi et al., 2021; Daraji et al., 2019) (Luca, 2006; Zhu and Bienaymé, 2006) Such imidazole analogues are also biologically active compounds and possess a broad spectrum of biological activities such as anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, analgesics, fungicidal, anti-bacterial, and plant growth regulations (Blevins et al., 2019; Dao et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018). After the investigation of facile synthetic methods which are pioneered by Debus (Wang et al., 2017)(and Radziszewski (Freedman and Loscalzo, 2016), the intriguing photophysical properties of 2,4,5-trisubstituted and 1,2,4,5-tetrasubstituted imidazoles have gained substantial attractions among researchers in recent decades(Dipake et al., 2022; Mirjalili et al., 2012). Recently, extensive ingenious researches are reported by several research groups to fabricate white light-emitting materials through a combination of proton transfer and restricted energy transfer using such kind of imidazole scaffolds with suitable donor–acceptor substituents (Huang et al., 2012; Mikhaylov et al., 2020; Tolomeu and Fraga, 2023).

The excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) has gained considerable attraction from theoretical as well as experimental perspectives due to its large Stoke’s shifted fluorescence emission. Most of the ESIPT reactions involve proton transfer from a pre-existing hydrogen bond, giving rise to proton-transferred keto tautomer in the excited state, and therefore widely accepted as an interesting phenomenon(Hristova et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2012). Due to their drastic structural alternation, the keto (K) tautomer possesses different photophysical properties from that of the original (enol (E)) species, offering great versatility in a variety of applications such as lasing materials (Chen et al., 2014; Elsässer and Becker, 2013; Hsieh et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2010; Machado et al., 2021)), UV photostabilizers (Scarpin et al., 2021), optical filters (Kuila et al., 1999; Tsentalovich et al., 2006), radiation scintillators (Sherin et al., 2009, 2008), molecular recognition, and fluorescent probes respectively(Uenuma et al., 2021). The most recent cutting edge application have mainly focused on the lighting materials (Murata et al., 2007). The ultrafast rate of ESIPT, together with a large Stokes’ shift between absorption and tautomer emission (peak–to–peak) provides a broad spectral window to fill in other complementary emissions from energy transfer and reabsorption. Many functional dyes display ESIPT, (e.g. flavones(Pariat et al., 2021)), 10-hydroxybenzo[h]quinoline (Kim et al., 2011), imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines (Park et al., 2009), 2-hydroxyphenylbenzoxazoles, and 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl) imidazole analogues are known to exhibit a high fluorescence quantum yields (Sun et al., 2009). Therefore, it will be more fascinating to understand the structure–property relationship of this category of compounds owing to its impact of π nature of the tetra-substituted imidazoles on the photophysical properties with solvent effect(Hariharan et al., 2018). Additionally, the substituted imidazole derivatives are one of the most significant pharmacologically active compounds of natural products(Gurudutta et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005, 2011; Park et al., 2009; Peng et al., 2011; Serdaliyeva D, Nurgozhin T, Satbayeva E, Khayitova M, Seitaliyeva A, 2022; Sharma et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2009), and the members of this category are well-known to possess nitric oxide synthase inhibition, anti-mycotic, anti-biotic, anti-ulcerative, and CB1 receptor antagonistic activities (Serdaliyeva D, Nurgozhin T, Satbayeva E, Khayitova M, Seitaliyeva A, 2022; Sharma et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2002), together with inhibitor activities of p38 MAP kinase (Magnus et al., 2006; Takle et al., 2006), β-Raf kinase (Naureen et al., 2015), glucagon receptors (de Laszlo et al., 1999), and therapeutic agents (Heeres et al., 1979). Similarly, substituted benzimidazole derivatives (Schmierer et al., 1988; Sharma et al., 2021) and the tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives (Heeres et al., 1979) (Ali et al., 2017) were reported to possesses α-glycosidase, anti-cancer and urease, respectively. Keeping all the above considerations, our research group have designed, synthesized, and characterized these π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and non-fused tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives. Along with experimental studies, semi-empirical calculations were also carried out using density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT), especially about critical hydrogen bonding by changing the ground and excited state geometry and Mulliken charge distribution analysis. Finally, the urease inhibitory activity and anti-cancer properties of ESIPT molecules were evaluated by in vitro and in silico method.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Chemistry

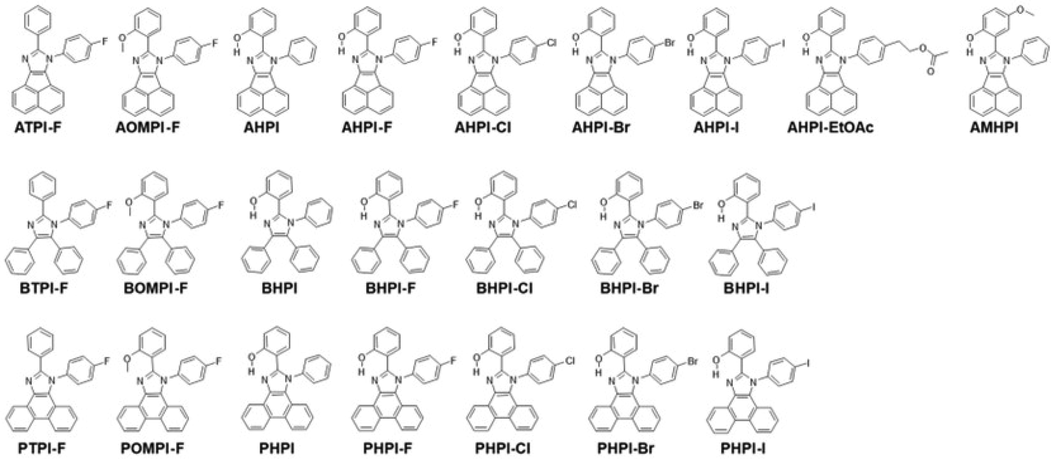

Scheme 1 illustrates the synthetic routes and the molecular structures of tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives, and the detailed molecular information are listed in Table 1. From the literature, the absorption and emission wavelength range of HPI and its derivatives are at 300–320 nm and 460–570 nm, respectively (Skonieczny et al., 2012). We have synthesized these imidazole derivatives based on the presence and nature of π-fusion, and π-extension of the chromophore would determine the photophysical properties, and therefore recommended the selection of different kinds of 1,2-diketones. To identify the substitution effect of 4-halophenyl group on the 1-position of imidazole and block of hydroxyl group, a library of twenty-three tetra-substituted imidazole molecules were synthesized with three different categories of 1,2-diketones such as π-non fused benzil, π-fused acenaphthoquinone, and π-extended 1,10-phenanthroquinone, as shown in Fig. 1.![Synthesis of π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra-phenyl imidazoles.](/content/184/2023/16/9/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.105030-fig1.png)

Synthesis of π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra-phenyl imidazoles.

S. No.

Compound Name

α-diketone

R

R1

X

1

PTPI-F

Phenanthroquinone (π–extended)H

H

F

2

POMPI-F

OCH3

H

F

3

PHPI

OH

H

H

4

PHPI-F

OH

H

F

5

PHPI-Cl

OH

H

Cl

6

PHPI-Br

OH

H

Br

7

PHPI-I

OH

H

I

8

ATPI-F

Acenaphthoquinone (π–fused)H

H

F

9

AOMPI-F

OCH3

H

F

10

AHPI

OH

H

H

11

AHPI-F

OH

H

F

12

AHPI-Cl

OH

H

Cl

13

AHPI-Br

OH

H

Br

14

AHPI-I

OH

H

I

15

AHPI-EtoAc

OH

H

CH2CH2OCOCH3

16

AMHPI

OH

OCH3

H

17

BTPI-F

Benzil (π–non fused)H

H

F

18

BOMPI-F

OCH3

H

F

19

BHPI

OH

H

H

20

BHPI-F

OH

H

F

21

BHPI-Cl

OH

H

Cl

22

BHPI-Br

OH

H

Br

23

BHPI-I

OH

H

I

Molecular structures of π-Extended, π-fused, and non-fused tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives.

The designed imidazole compounds were synthesized via classical Debus-Radziszewski one-pot multi-component reaction from 1,2-diketones with corresponding aromatic aldehydes, aromatic amines, and ammonium acetate with refluxing in acetic acid. The products were isolated with relatively good yield (65 to 75%) and single clean crystal was obtained from ethyl acetate by slow evaporation technique. The obtained imidazole derivatives were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy (Fig. S1–S46), GC–MS spectroscopy, and elemental analysis (EA). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of all compounds are in agreement with the molecular structure, and chemical shifts of the resonance associated with the proton and carbon atoms of these molecules are in the acceptable range. The molecular mass of all the compounds corresponds to the mass spectrum results. Single crystal X-ray crystallography was used to confirm further the solid-state geometry of some of the representative imidazole molecules such as AHPI-F, AHPI-Cl, AHPI-Br, BHPI-Cl, and BHPI-Br and these results were already reported in our previous publications. (Parkin et al., 2001; Somasundaram et al., 2017). The crystallographic results revealed that crystals of AHPI-F, AHPI-Cl, and AHPI-Br are in monoclinic crystal system with P21/c space group and the crystals of BHPI-Cl and BHPI-Br are orthorhombic crystal system with P212121 space group.

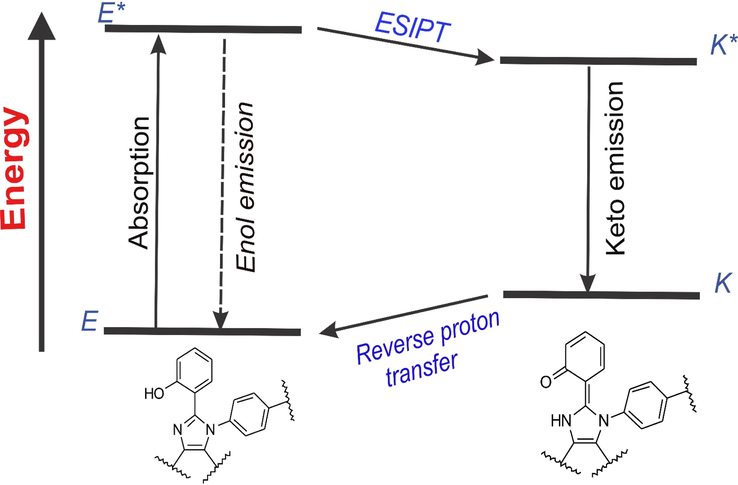

2.2 ESIPT phenomenon

All the synthesized imidazole molecules except ATPI-F, AOMPI-F, BTPI-F, BOMPI-F, PTPI-F and POMPI-F are possessing an acidic hydroxyl group at the ortho-position to phenyl ring which is directly attached to the imidazole core at position 2′. The existence of the intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the ground state is supported by the location of hydroxyl (–OH) and imine (=N–) groups as illustrated in the Fig. 2. During photoexcitation, the imine group (=N–), and the hydroxyl (–OH) group tend to become strong basic and acidic respectively as shown by the changes in the ground and excited states by Mulliken charge distribution (Table 2). Due to this, the excited-state enol form (E*) is converted to the excited-state keto form (K*) (Fig. 1) which results in the ESIPT. Briefly, upon UV light irradiation, absorption of light excites the ground state enol (E) state to the excited state (E*). Then, the E* either undergoes mainly the ESIPT by fast proton transfer to K* or returns to the ground state enol (E) form by emitting the ‘enol’ emission (E*→E). After ESIPT process, the excited keto form (K*) returns to the keto ground state (K) by releasing its radiation, which is called the ‘keto’ emission (K*→K). By this way of the 4-level ESIPT process (Fig. 2), these molecules exhibit absorption and characteristic large stokes shifted emission.

Pictorial expression of 4-level ESIPT process and the intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the tetra-substituted imidazole system.

S. No.

Compounds

Oxygen

Nitrogen

S0

S1

S0

S1

1

ATPI-F

–

–

–

–

2

AOMPI-F

–

–

–

–

3

AHPI

−0.770

−1.268

−0.592

−1.730

4

AHPI-F

−0.790

−0.771

−0.595

−0.982

5

AHPI-Cl

−1.110

−0.771

−0.594

−1.408

6

AHPI-Br

−0.780

−0.771

−0.594

−0.981

7

AHPI-I

−0.630

−0.625

−0.595

−0.717

8

AHPI-EtoAc

−0.780

−0.771

−0.593

−0.980

9

AMHPI

−0.80

−0.786

−0.591

−0.978

10

BTPI-F

–

–

–

–

11

BOMPI-F

–

–

–

–

12

BHPI

−0.780

−0.637

−0.747

−0.973

13

BHPI-F

−0.77

−0.783

−0.73

−0.973

14

BHPI-Cl

0.636

−0.783

0.746

−0.975

15

BHPI-Br

−0.77

−0.783

−0.729

−0.976

16

BHPI-I

−0.64

−0.783

−0.746

−0.975

17

PTPI-F

–

–

–

–

18

POMPI-F

–

–

–

–

19

PHPI

−0.77

−0.765

−0.699

−0.858

20

PHPI-F

0.771

−0.765

0.702

−0.861

21

PHPI-Cl

−0.77

−0.765

−0.702

−0.861

22

PHPI-Br

−0.77

−0.765

−0.701

−0.860

23

PHPI-I

−0.77

−0.765

−0.702

−0.861

2.3 Photophysical properties

The absorption and emission spectra of all the imidazole derivatives were studied in a dilute solution (10–5 molL–1) of three categories of solvents with different proticity and dielectric constants, non-polar chloroform (CHCl3), polar protic ethanol (EtOH) and polar aprotic acetonitrile (MeCN) at room temperature. To understand the complexity of the ESIPT process of synthesized imidazole derivatives and its efficiency under internal and external parameters such as structural modification and solvent nature, we compared the spectral properties with non-ESIPT analogues. Molar absorptivity and corresponding absorption maxima, emission maxima, Stokes’ shifts, and fluorescence quantum yields are given in Table S1-S3.

The absorption and emission spectra of π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra substituted imidazole series were studied in Fig. S47–S49. The respective absorption spectra are characterized by a band in the 250–400 nm range which are due to a π → π* transition corresponding to excitation of aromatic electrons (Fig. 2). The absorption band around 300 nm (ATPI-F, AOMPI-F), 250 nm (BTPI-F, BOMPI-F), and 320 nm (PTPI-F, POMPI-F) are probably due to neutral/unsolved open conformer of non-ESIPT system. The absorption maxima are negligibly sensitive to solvent polarity (Alarcos et al., 2015; Chowdhury et al., 2003; Mahanta et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2004). The slight redshifts of AHPI, BHPI and PHPI series compared to the ATPI-F, AOMPI-F, BTPI-F, BOMPI-F, PTPI-F and POMPI-F due to the presence of an intramolecular hydrogen bond making larger the π electronic configuration. On other hand, the insensitivity of the absorption spectra of these molecules to the solvent polarity indicates that the dipole moments of compounds in the ground state are nearly identical. The presence of halogen and ester functional groups in all AHPI-F, AHPI-Cl, AHPI-Br, AHPI-EtOAc, BHPI-F, BHPI-Cl, BHPI-Br, BHPI-I, PHPI-F, PHPI-Cl, PHPI-Br, and PHPI-I exhibits the S0 → S1 transition, which is relatively the same energies with their parent molecules as AHPI, BHPI and PHPI (whose absorption maximum is around 325 nm, 320 nm and 365 nm) (Skonieczny et al., 2012). In AMHPI absorption spectrum, hypsochromic shift was observed in chloroform, while ATPI-F showed bathochromic shifted absorption in ethanol solvent system. This variation is ascribable to the intermolecular interaction between solvent system and fluorescent molecules.

The fluorescence emission spectra of all π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra-phenyl substituted imidazole molecules consists of a unique band whose maximum is also shifted with the solvent effect. A prominent single emission peak in the range of 450–600 nm was observed in all the samples. The presence of these unique Stokes’ shifted emission peaks indicated that the fluorescence property of these molecules was not quenched (except AOMPI-F (in CHCl3), AMHPI (in CHCl3, MeCN, and EtOH) even in solid-state. In nonpolar organic solvents, all the compounds of AHPI, BHPI, and PHPI series showed the emission at 569 nm, 469–483 nm, and 477 nm, respectively.

Similarly, in polar protic solvent and a polar aprotic solvent such as EtOH and MeCN, emission band at around 578 nm (AHPI series), 474 nm (BHPI series), 477–480 nm (PHPI series), and 556–560 nm (AHPI series), 474 nm (BHPI series) (PHPI series) were observed (Fig. S47–S49). The keto emission shows a remarkable redshift from 556 nm (in EtOH) to 572 nm (in CHCl3) due to intermolecular interaction between solvent molecules and imidazoles, and similar emission properties are reported by Skonieczny et al.(Skonieczny et al., 2012). The emission of all compounds at > 450 nm can be assigned to the radiative decay of the excited keto tautomer (K*). The emission of ATPI-F, AOMPI-F, BTPI-F, BOMPI-F, PTPI-F, and POMPI-F confirmed these postulations. Compounds with a protected hydroxyl group (AOMPI-F, BOMPI-F, and POMPI-F) and without hydroxyl group (ATPI-F, BTPI-F, and PTPI-F) showed almost same emission in both protic and aprotic solvents, indicating the absence of ESIPT. From the photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy results, the emission shift tendency can be concluded to following order of π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazoles > π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d] imidazoles > π-non fused tetra phenyl substituted imidazoles. The longer emission of π-fused and π-extended system of imidazoles is probably due to the high π–π stacking interaction of planner geometry. The π-non fused system has relatively shorter emission wavelength compared to the other two systems. On the other hand, the large Stokes shifted emission spectra (Table S1–S3) according to the increased number of conjugated aromatic ring systems reflected the existence of intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) which takes place in the excited state keto-enol tautomer, thus resulting in significant changes in the optical properties.

Fluorescence quantum yields (ϕPL) of compounds possessing π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d] imidazole and π-non fused tetra-phenyl substituted imidazole cores showed different characteristics due to its sensitivity to the solvent polarity (Table S1–S3). It is observed that the quantum yields are higher in polar aprotic solvents and this can be attributed to longer emission lifetime due to the hydrogen bond between molecule and solvent system. Comparably, quantum yields are the highest in acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole derivatives and the least in tetraphenyl substituted imidazole derivatives.

2.4 Electronic spectra and frontier molecular orbitals: Computational studies

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to characterize the optimized molecular geometries, frontier molecular orbital energy levels, and relative absorption spectra for π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d] imidazole, π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, and π-non fused tetra phenyl substituted imidazoles at B3LYP/6–31 G (d, p) level by using Gaussian 09 program. The ground and excited state geometries of the fluorophores in both E and K forms were optimized with DFT/TD-DFT method. The theoretical UV–vis. absorption of synthesized compounds was calculated by TD-DFT method.

The DFT and TD-DFT method have been adopted to optimize the structure for the molecules in S0 and S1 state, respectively. The optimized geometries with intramolecular hydrogen bonds of AHPI, BHPI, and PHPI are shown in Fig. 3. Among twenty-three structures of stable isomers, we have displayed representative three molecules, because all the molecules of those three categories have similar geometry. To make the description of bond length and bond angle clearer and more concise, the hydrogen-bonded atoms have been numbered. We listed the most important structural parameters in Table 3, which were calculated by the B3LYP/6–31 G (d, p) basic set. Based on the calculated results, it is worth noting that the bond lengths of O1-H2, H2-N3 of phenanthro[9,10-d] imidazole are 0.964 Å, acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole structure is 0.968 Å, and tetraphenyl substituted imidazole is 0.972 Å in the ground state (S0) state, respectively. However, after being excited to S1 state, the bond lengths are 0.984 Å, 0.984 Å, and 0.981, respectively. Meanwhile, the O1-H2-N3 bond angle varies from 146.3 to 148.2°, 146.9–147.9° and 143.5-144° in S1 state to 122.6–122.7°, 123.1° and 132.3° in S0 state. Significantly, the bond length of O1-H2 is longer as well as H2-N3 is shorter in the excited S1 state, which indicates that the intramolecular hydrogen bonds are simultaneously enhanced in the excited S1 state and in the bond angle of O1-H2∙∙∙N3 was higher than in S0 state respectively. From the above results, it is indicated that the intramolecular hydrogen bond O1-H2∙∙∙N3 is more stable in the S1 state than that in the ground state.![Optimized geometries of (a) π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], (b) π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, and (c) π-non fused tetra phenyl substituted imidazole using DFT calculations with the B3LYP/6–31 G(d,p) parameter. Red. O; white. H; Blue. N; gray. C atom.](/content/184/2023/16/9/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.105030-fig4.png)

Optimized geometries of (a) π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], (b) π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, and (c) π-non fused tetra phenyl substituted imidazole using DFT calculations with the B3LYP/6–31 G(d,p) parameter. Red. O; white. H; Blue. N; gray. C atom.

S. No.

Compounds

O1-H2

H2-N3

δ (O1-H2-N3)

S0

S1

S0

S1

S0

S1

1

ATPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

2

AOMPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

3

AHPI

0.968

0.984

1.872

1.806

122.7

146.9

4

AHPI-F

0.968

0.984

1.873

1.810

122.7

146.8

5

AHPI-Cl

0.968

0.984

1.873

1.804

122.7

146.9

6

AHPI-Br

0.968

0.984

1.873

1.744

122.6

147.2

7

AHPI-I

0.968

0.984

1.873

1.795

122.7

148.2

8

AHPI-EtOAc

0.968

0.983

1.873

1.855

122.6

146.3

9

AMHPI

0.968

0.984

1.875

1.798

122.7

147.0

10

BTPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

11

BOMPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

12

BHPI

0.968

0.984

1.869

1.741

123.1

147.3

13

BHPI-F

0.968

0.984

1.870

1.741

123.1

147.3

14

BHPI-Cl

0.968

0.984

1.870

1.795

123.1

146.9

15

BHPI-Br

0.968

0.984

1.870

1.744

123.1

147.2

16

BHPI-I

0.968

0.984

1.870

1.743

123.1

147.3

17

PTPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

18

POMPI-F

–

–

–

–

–

–

19

PHPI

0.972

0.982

2.100

1.981

132.3

144.0

20

PHPI-F

0.972

0.981

2.195

2.002

132.3

143.5

21

PHPI-Cl

0.972

0.981

2.195

2.003

132.3

143.5

22

PHPI-Br

0.972

0.981

2.195

1.997

132.3

143.6

23

PHPI-I

0.972

0.981

2.195

2.001

132.3

143.5

The calculated absorption maxima (by TD-DFT-B3LYP/6-31G (d, p) theoretical level) of π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d] imidazole, and π-non fused tetra phenyl substituted imidazole is at 300–480 nm, 300–370 nm, and 324–569 nm, which is in good agreement with the experimental results. The prominent intense absorption can be assigned to HOMO–2 to LUMO transition and the other absorption arises from HOMO-LUMO transition. To further investigate the nature of the charge distribution and charge transfer in the electronically excited state, the frontier molecular orbital of all three imidazole families are depicted in Fig. 4. The calculated electronic excitation energies and corresponding oscillator strengths of the first three states for all molecules are listed in Table S1, S2, and S3. The oscillator strength of S0 → S1 transition of π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole, π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d] and π-non fused tetra substituted imidazole are 0.0644–0.0721, 0.2193–0.3099 and 0.0781–0.0922 respectively, showing that the enol-keto tautomer has a positive effect. According to Kasha’s rules, we have discussed only the first electronic excited state (HOMO and LUMO energy levels) of the molecules. It is noted that, the HOMO orbitals of the studied molecular system are π type orbitals while the LUMO orbitals are π* character, indicating that the first excited states are the π → π* type transition from HOMO to LUMO. The HOMO and LUMO are localized on different parts of the molecules. In addition, the H∙∙∙N bonds in the LUMO orbital have σ character, showing that the N atoms with electron pair donation ability can form a covalent bond with the H atoms after photoexcitation to the S1 state. The electron density on the hydroxyl group decreases upon excitation, whereas the electron density on the N atom of imidazole moiety increased upon photoexcitation. The changes in the electron density indicated both the acidity of the hydroxyl group and the basicity of the N atom group have increased upon excitation, which coincides with the occurrence of ESIPT. The calculated Mülliken charges of the hydroxyl moiety O atom and the neighbouring N atom for all molecules except ATPI-F, AOMPI-F, BTPI-F, BOMPI-F, PTPI-F, and POMPI-F are shown in Table 2. Upon transition from the HOMO to LUMO, the decrease of electron density in the hydroxyl moiety and the increase in N atoms were expected to directly influence the intramolecular hydrogen bonding. That is, the H∙∙∙N bonds length becomes shorter upon excitation to S1 state. From the viewpoint of the valence bond theory, the transition from S0 → S1 state leads to more negative charge contributed on the N atoms and the enlarged interaction between the lone pair electron of N atoms and the σ*(O–H) orbitals will facilitate ESIPT processes from O atom to N atom. Therefore, the ESIPT is expected to occur due to the intramolecular charge transfer.![Calculated frontier molecular orbital diagram (Iso value 0.02) for A. acenapthol [1,2-d] imidazole, B. Phenanthro [9,10-d] imidazole, and C. tetra phenyl substituted imidazole using TD-DFT/B3LYP (6–31 G) (d,p) theoretical level.](/content/184/2023/16/9/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.105030-fig5.png)

Calculated frontier molecular orbital diagram (Iso value 0.02) for A. acenapthol [1,2-d] imidazole, B. Phenanthro [9,10-d] imidazole, and C. tetra phenyl substituted imidazole using TD-DFT/B3LYP (6–31 G) (d,p) theoretical level.

2.5 Urease inhibition activity-Structural activity relationship (SAR)

The evaluation of urease inhibition was carried out for the synthesized twenty-three imidazole molecules of three different π-systems using thiourea as a reference standard which showed IC50 value of 16.14 ± 0.072 µM for this urease inhibition experiments. These imidazole derivatives showed varying degrees of inhibition against urease activity in the range of 0.0288 ± 0.0034 to 0.1709 ± 0.00496 µM respectively. Though the observed inhibition potential is the resultant of a whole molecule, a limited structure–activity relationship (SAR) was rationalized by considering the effect of different functional groups including hydroxyl, methoxy, halogens, acetoethyl and the π nature such as extended, fused, and non-fused present in the imidazole on the inhibitory potential.

Amongst π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole compounds containing halogen atom (F, Cl, Br and I) in their respective imidazole N-substitution, inhibition potential varies due to presence of halogen atom and presence or absence of the o-hydroxy group in the phenyl ring substituted in 2-position to imidazole core. All imidazole molecules exhibited significant inhibitory activity compared to the standard thiourea except the compound ATPI-F, showed least inhibitory activity (IC50 0.0474 ± 0.00154 µM) due to high electronegative fluorine atom and no OH group. Likewise, AMHPI and AHPI-EtOAc also showed decreased inhibition activity against urease due to the presence of –OCH3 donor group in para position to the –OH of AMHPI and –EtOAc group in N-substitution of AHPI-EtOAc respectively. Whereas, POMPI-F (IC50 0.0289 ± 0.0025 µM) and BTPI-F (IC50 0.031 ± 0.00127 µM) exhibited the most significant inhibitory activity against urease among the other respective family of imidazole derivatives. The possible reason might be due to the interaction of OH and halogen groups on the aromatic system (π-fused acenaphtho and π-extended phenanthro system) that allowed to bind with nickel atom present in the urease enzyme. The urease activity of all the compounds shown in Table 4 compared with reference compound thiourea.

Compounds

Urease activity IC50 ± SEM (µM)

Compounds

Urease activity IC50 ± SEM (µM)

Compound

Urease activity IC50 ± SEM (µM)

ATPI-F

0.0474 ± 0.00154

BTPI-F

0.031 ± 0.00127

PTPI-F

0.0522 ± 0.00154

AOMPI-F

0.039 ± 0.00125

BOMPI-F

0.041 ± 0.00142

POMPI-F

0.0289 ± 0.0025

AHPI

0.029 ± 0.0020

BHPI

0.0323 ± 0.0011

PHPI

0.0299 ± 0.0014

AHPI-F

0.089 ± 0.0047

BHPI-F

0.0318 ± 0.0021

PHPI-F

0.031 ± 0.0021

AHPI-Cl

0.0307 ± 0.0010

BHPI-Cl

0.1709 ± 0.00496

PHPI-Cl

0.0358 ± 0.00154

AHPI-Br

0.0288 ± 0.0034

BHPI-Br

0.0301 ± 0.0092

PHPI-Br

0.0451 ± 0.00156

AHPI-I

0.0473 ± 0.00021

BHPI-I

0.0701 ± 0.00094

PHPI-I

0.0681 ± 0.00165

AHPI-EtOAc

0.0506 ± 0.00176

Thiourea

16.14 ± 0.072

AMHPI

0.0807 ± 0.0028

2.6 Kinetic mechanism

Based on the inhibitory potential, presently two compounds AHPI-Br and POMPI-F were studied for their mode of inhibition against urease. The potential of these two compounds to inhibit the free enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex was determined in terms of EI and ESI constants respectively. The kinetic studies of the enzyme by the Lineweaver-Burk plot of 1/V versus 1/[S] in the presence of different inhibitors concentrations gave a series of straight lines as shown in Figure S50 (A) and (D) displayed compounds AHPI-Br and POMPI-F intersection within the second.

quadrant. The analysis showed that Vmax decreased with increasing Km in the presence of increasing concentrations of compounds AHPI-Br and POMPI-F. This behaviour of AHPI-Br and POMPI-F derivatives indicated that it inhibits the urease by two different pathways competitively forming enzyme inhibitor (EI) complex and causing the interruption of enzyme-substrate-inhibitor (ESI) complex in a non-competitive manner. The secondary plots of slope versus concentration of compounds such as AHPI-Br and POMPI-F showed EI dissociation constants Ki Figure S50 (B) and (E) while ESI dissociation constants Ki′ were shown by secondary plots of intercept versus concentration of compounds AHPI-Br and POMPI-F Fig S50 (C) and (F). A lower value of Ki than Ki′ pointed out stronger binding between enzyme and compounds API-Br and POMPI-F which suggested the competitive over non-competitive manners. The results of kinetic constants and inhibition constants are presented in Table S4.

2.7 Docking studies

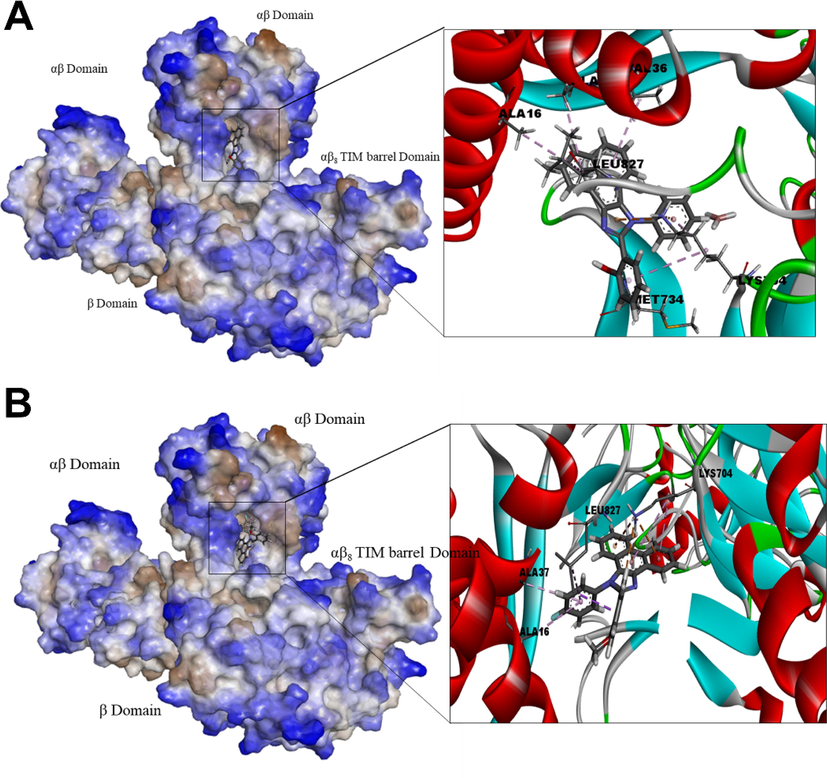

The docked files (ligand and receptor complex) were stored in.pdb format and visualized using a tool Discovery studio visualizer. The best poses were identified based on the number of interactions, a ligand has made and RMSD (Table 5). The identified pose was extracted for detailed observation and extracting the snaps. For the 3-D representation of binding of ligand was captured in ‘solid ribbons presentation’ of receptor and ligands were presented in “solid sticks presentation”. The 2D interaction map was also captured.

Protein

Ligand

Binding energy (kcal/mol)

RMSD (LB)

RMSD (UB)

Interacting residues

BCl2

PHPI

−8.9

1.743

2.197

Phe198, Leu201, Glu209

BCl2

PHPI-Cl

−9.4

2.054

4.896

Ala100, Trp144, Phe198, Leu201, Glu209

BCl-Xl

PHPI

−7.9

2.257

5.24

Leu54, Ala88

BCl-Xl

PHPI-Cl

−8.4

1.757

2.957

Lys20, Glu44, Ala50, Ala95

Urease

AHPI-Br

−10.3

1.531

1.872

Ala16, Thr33, Val36, Ala37, Lys704, Met734, Leu827

Urease

POMPI-F

−9.7

2.16

5.079

Ala37, Lys704, Leu827

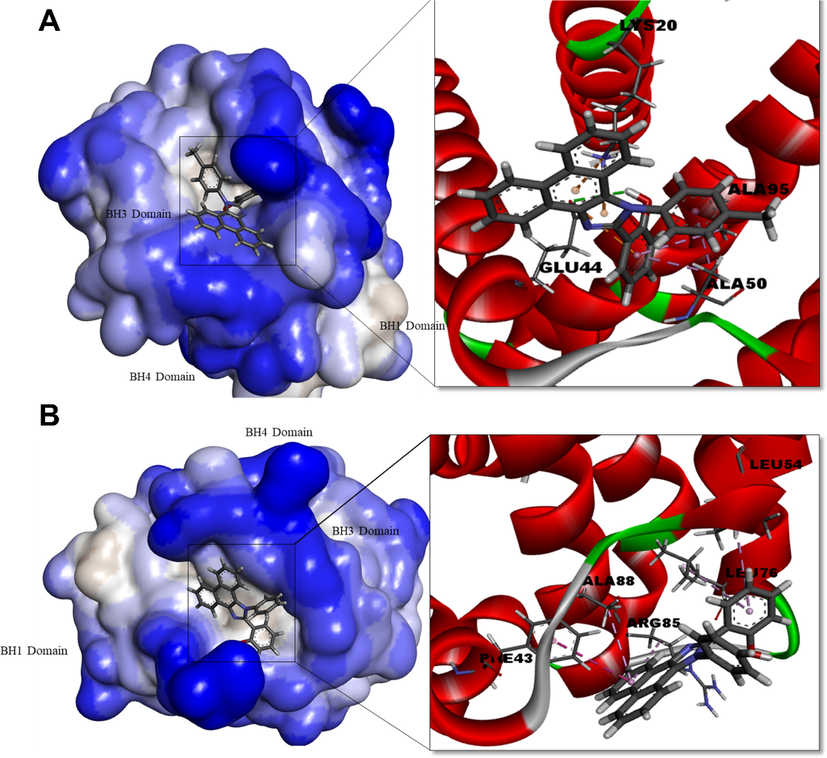

Bcl-xl: Docking of Bcl-xl with PHPI-CI observed a binding energy of −8.4 kcal/mol as compared to PHPI −7.9 kcal/mol. PHPI formed π -alkyl bonds with leu54 and Ala88; whereas Bcl-xl-PHPI-Cl formed Vander Waal bonds (Lys20), π -sigma (Ala50), π -aklyl (Ala95) (Fig. 5).

Human Bcl-xl protein complexed with PHPI (A) and PHPI-Cl (B). Surface representation of the protein structure displays ligand bound in the active site cavity of the receptor (left) and 3D interaction of ligand and receptor showing key interactions (right).

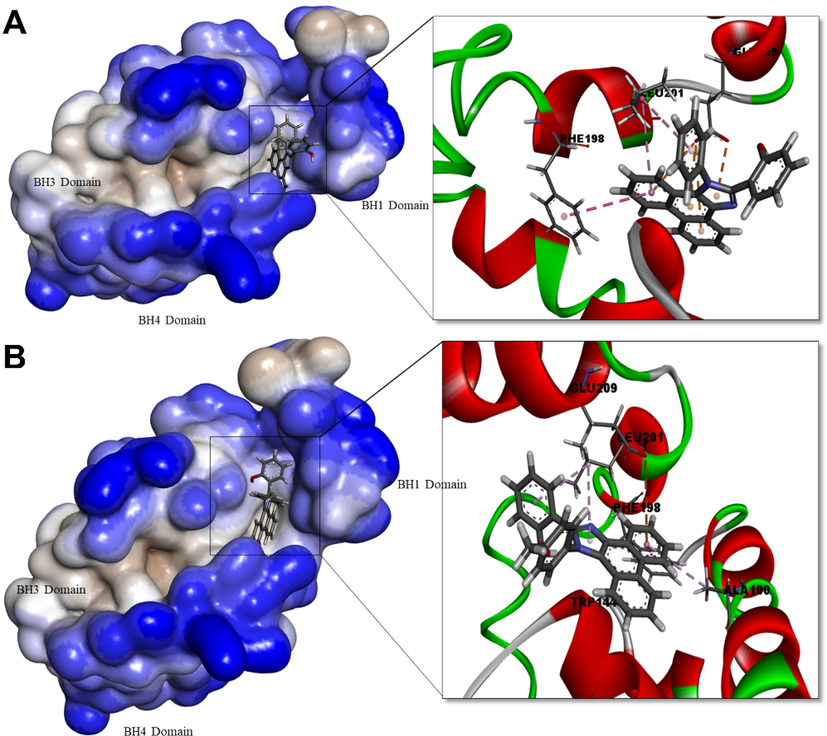

Bcl-2: Ligands PHP-I and PHPI-CI bound with Bcl-2 with a binding energy of −9.4 kcal/mol however, PHPI exhibited binding energy of −8.9 kcal/mol. PHPI interacted with Bcl-2- with Glu209 by a π -anion, with Phe198 by π- π and with Leu201 by π-alkyl interaction. No H-bonds were noticed. The ligand PHPI-Cl forms a conventional H-bond with Trp144 and a π -alkyl with Ala100 (Fig. 6).

Human Bcl-2 protein complexed with PHPI (A) and PHPI-Cl (B). Surface representation of the protein structure displays ligand bound in the active site cavity of the receptor (left) and 3D interaction of ligand and receptor showing key interactions (right).

Urease: The ligand AHPI-Br and POMPI-F bound to the defined active site by the binding energy −10.3 kcal/mol as however, POMPI-F with urease exhibited −9.7 kcal/mol with LB-RMSD 1.53 and 2.16 A respectively. Urease with AHPI-Br formed mainly π -sigma (Val36, Ala37, Leu827, Met734, Lys704); whereas POMPI-F with urease formed π -cation (Lys704), π -alkyl (Ala37) and π -sigma (Leu827) (Fig. 7). Since, metal Ni is an important for urease for activity, hence observing interaction with Ni could be interesting. But, the presence of water molecules within the binding cavity is important for establishing the coordination of metal Ni (Nim and Wong, 2019). The lack of observed interaction with Ni in the docking process may be attributed to the non-aqueous environment used. However, molecular dynamic simulation of the docked complex for at least 200 ns could certainly provide further insights particularly regarding sustained interactions over the course of the simulation. Further, the interaction of OH and halogen groups can affect the inhibitory activity of urease (Rashid et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2020). However, no such interaction has been observed in both POMPI-F and AHPI-Br (Fig. 7).

Jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis) urease docked with POMPI-F (A), and AHPI-Br (B). Surface representation of the protein structure displays ligand bound in the active site cavity of the receptor (left) and 3D interaction of ligand and receptor showing key interactions (right).

2.8 Anti-cancer activity

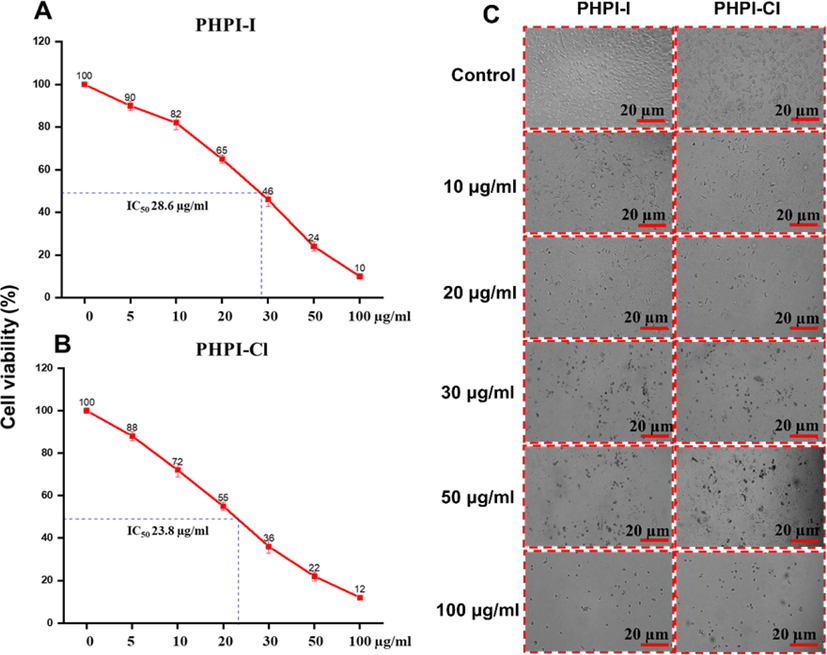

The MTT results showed the PHPI-I and PHPI-Cl possessed the strong anti-proliferative activity among other imidazole derivatives against AGS cell line in a dose-depending manner (Fig. 8 A-C). Later, the morphological observation of both untreated and treated AGS cell line was observed it showed significant induction of cell death compared with untreated cell lines (Fig. 8C). Cancer cells modulate the apoptosis process by regulating.

Cell viability and morphological changes with or without PHPI or PHPI-CI treatment. A. PHPI-I treatment, B. PHPI-CI treatment, and C. Morphological characteristics of AGS cell lines were observed in a dose dependent manner with or without PHPI-I or PHPI-CI treatment. The experiment was carried out independently in triplicates and the represented images were shown.

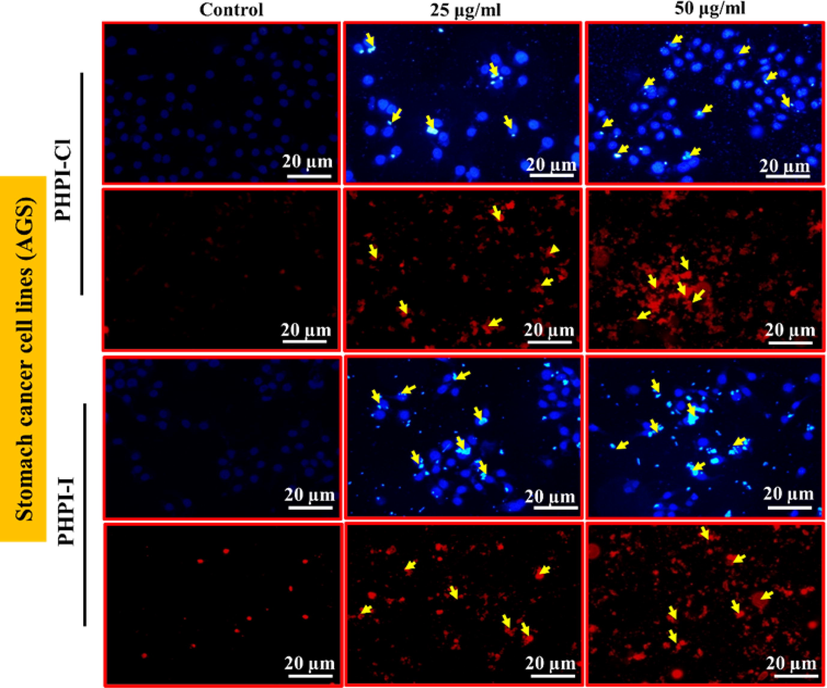

transcription, translation, and by post-translational modification and therefore causing cancer cells to escape apoptotic process (Fernald and Kurokawa, 2013). Determination of apoptotic cell death of detection on AGS cell line was performed by both hoechst and propidium iodide staining analysis. With or without PHPI-I or PHPI-Cl treatment (25 and 50 µg/ml), showed dose dependent visible chromatin condensation and degradation of nuclei in AGS cells (Fig. 9). When looking inside the cell, one of the most obvious features of apoptosis is the condensation of the nucleus and its fragmented segments (Taylor et al., 2008). Therefore, our results indicated that PHPI-I and PHPI-Cl could act as a promising anti-cancer agent by targeting apoptotic cell death mechanism.

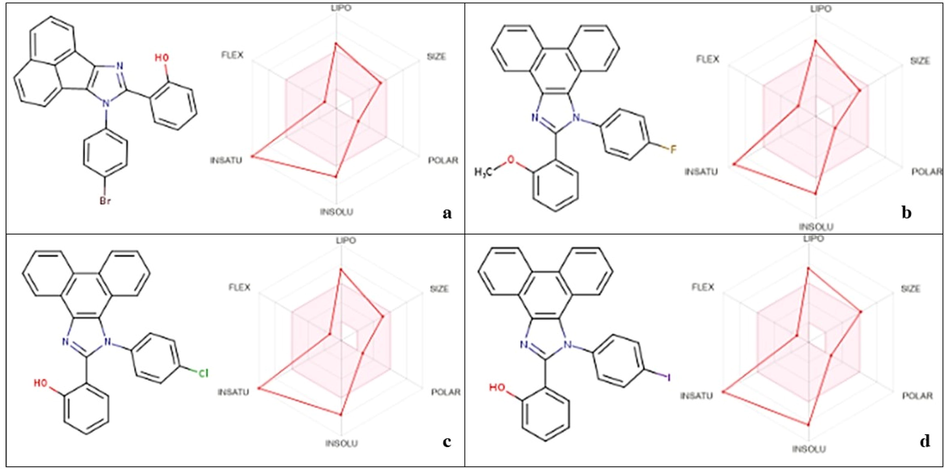

In-silico ADME analysis of potential derivatives represents the drug likness parameters lying in the feasible region (presented in the pink region) a. AHPI-Br; b. POMPI-F; c. PHPI-Cl; d. PHPI-I.

The SwissADME server used for ADME analysis of imidazole derivatives was useful to highlight the drug-likeness properties. According to previous studies, compounds with molecular weight ≤ 500 g/mol, recommended Log S (aqueous solubility) between − 6.5–0.5, HBD between 0 and 6 and HBA between 2 and 10, and Lipophilicity (Log P) to predict BBB permeability as well as gastrointestinal (GI) absorption ≤ 5, and TPSA ≤ 140 Å2 are considered as optimal drug candidates(Alghamdi et al., 2021; Bouchery and Harris, 2019). Comparing the SwissADME reports, it was observed that the targeted compounds to be sub-optimal for toxicity for drug-likeness properties Fig. 10.

Hoechst and Propidium iodide (PI) staining of AGS cells. Arrow indicates the cell death after PHPI or PHPI-CI treatment. The experiment was carried out independently in triplicates and the represented images were shown.

3 Experimental section

3.1 Chemistry

All the chemicals obtained from commercial suppliers were used as received unless noted. Reaction progress was monitored by using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with commercial TLC plates (silica gel 60 F254, Merck Co.) and Chromatography was used to purify the product on silica gel (60–120 mess). Chemical structures of the synthesized molecules were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR recorded on Bruker 300 MHz, and Oxford 400 MHz NMR instruments, high-resolution GC-mass spectrometry obtained from JEOL, JMS-AX505WA, and elemental analysis measured on CE Instrument, EA2220. Melting range measurements were collected from DegiMelt MPA161 instrument.

3.2 General procedure for the synthesis of π-extended phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra phenyl imidazoles.

Scheme 1 describes the synthesis of imidazole derivatives and the compounds with varying functional groups are listed in Table 1. α-diketone (1 eq.) and ammonium acetate (5 eq.) were added into a magnetically stirred solution of aryl aldehyde (1 eq.) and arylamine (1 eq.) in glacial acetic acid, at room temperature under nitrogen atmosphere. Refluxed the reaction mixture at 120 °C for 12 h and the progress was monitored by using TLC. After completion, the reaction mixture was cooled and poured into a copious amount of water. Filtered the product and washed with water until neutral pH. After then the product was dissolved in dichloromethane and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. Removed the solvent under reduced pressure to get the crude product and purified by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane–ethyl acetate mixture as eluent. Crystallization from ethyl acetate afforded crystalline solid by slow evaporation technique.

3.2.1 7-(4-fluorophenyl)-8-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole (ATPI-F)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 187–190 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.96 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 7.7, 4.6 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (dd, J = 8.3, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52 – 7.45 (m, 4H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.3, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.34 – 7.27 (m, 3H), 7.24 – 7.14 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.08 (s), 160.77 (s), 150.67 (s), 148.09 (s), 138.63 (s), 134.16 (d, J = 3.2 Hz), 131.74 (s), 130.55 (d, J = 12.0 Hz), 129.67 (s), 129.00 – 128.41 (m), 128.24 – 127.86 (m), 127.04 (dd, J = 23.5, 12.8 Hz), 121.04 (s), 118.81 (s), 117.24 (s), 116.94 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H15FN2: 362.12; found: 362 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C25H15FN2: C, 82.86; H, 4.17; F, 5.24; N, 7.73; found: C, 82.09; H, 4.34; N, 7.50.

3.2.2 7-(4-fluorophenyl)-8-(2-methoxyphenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazole (AOMPI-F)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 183–185 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.91 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.74 – 7.64 (m, 3H), 7.55 (dd, J = 8.3, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (ddd, J = 15.7, 11.5, 6.4 Hz, 5H), 7.08 (dt, J = 18.1, 7.9 Hz, 3H), 6.75 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.74 – 163.35 (m), 160.35 – 159.95 (m), 156.89 (s), 148.91 (s), 148.18 (s), 137.31 (s), 134.66 (s), 132.36 (s), 131.60 (s), 131.06 (d, J = 19.4 Hz), 129.67 (s), 128.04 (s), 127.53 – 126.81 (m), 126.81 – 126.18 (m), 120.93 (d, J = 18.7 Hz), 120.20 (s), 118.84 (s), 116.33 (s), 116.03 (s), 110.98 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s), 54.90 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H17FN2O: 392.13; found: 392 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C25H17FN2O: C, 79.58; H, 4.37; F, 4.84; N, 7.14; O, 4.08; found: C, 79.52; H, 4.48; N, 7.11; O, 5.30.

3.2.3 2-(7-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AHPI)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 200–203 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.88 (s, 1H), 7.91 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.68 – 7.53 (m, 6H), 7.39 – 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.21 – 6.98 (m, 3H),6.81 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.06 (s), 148.56 (s), 145.26 (s), 137.51 (s), 133.82 (s), 131.73 (s), 130.33 (s), 129.65 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 128.45 (s), 128.11 (s), 127.74 (s), 127.24 (s), 126.38 (s), 125.98 (s), 123.69 (s), 121.53 (s), 119.32 (s), 118.47 (d, J = 4.3 Hz), 118.16 (s), 113.58 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H16N2O: 360.13; found: 361 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd for C25H16N2O: C, 83.31; H, 4.47; N, 7.77; O, 4.44; found: C, 83.5322; H, 4.4733; N, 7.6054; O, 4.5530.

3.2.4 2-(7-(4-fluorophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AHPI-F)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 208–210 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.79 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.3, 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.59 – 7.47 (m, 3H), 7.38 – 7.24 (m, 3H), 7.22 – 7.04 (m, 2H), 6.98(d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.60 – 6.48 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.10 (s), 148.68 (s), 144.98 (s), 138.28 (s), 134.44 (s), 131.72 (s), 130.22 (s), 129.66 (s), 128.70 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 128.07 (s), 127.64 (s), 127.16 (s), 126.42 (s), 125.79 (s), 121.43 (s), 119.19 (s), 118.33 (s), 118.06 (s), 117.78 (s), 117.48 (s), 113.66 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H15FN2O: 378.12; found: 379 [M+]; Elemental analysis calcd. C25H15FN2O: C, 79.35; H, 4.00; F, 5.02; N, 7.40; O, 4.23; found: C, 79.3584; H, 4.1151; N, 7.4210; O, 4.3217.

3.2.5 2-(7-(4-chlorophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AHPI-Cl)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 195–199 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.70 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (dd, J = 8.2, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 7.66 – 7.47 (m, 5H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.3, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (ddd, J = 8.6, 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.13 – 7.00 (m, 2H), 6.79 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.63 – 6.51 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.08 (s), 148.62 (s), 136.99 (s), 135.73 (s), 130.84 (s), 130.32 (s), 129.70 (s), 128.15 (d, J = 4.6 Hz), 127.74 (s), 127.21 (s), 126.40 (s), 125.95 (s), 121.53 (s), 119.30 (s), 118.42 (s), 118.11 (s). δ 158.08 (s), 148.62 (s), 145.23 (s), 138.09 (s), 136.99 (s), 135.73 (s), 131.74 (s), 130.84 (s), 130.32 (s), 129.66 (d, J = 6.5 Hz), 128.15 (d, J = 4.6 Hz), 127.74 (s), 127.21 (s), 126.40 (s), 125.95 (s), 121.53 (s), 119.30 (s), 118.42 (s), 118.11 (s), 113.61 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H15ClN2O: 394.09; found: 394 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C25H15ClN2O: C, 76.05; H, 3.83; Cl, 8.98; N, 7.09; O, 4.05; found: C, 76.1480; H, 3.9217; N, 7.0767; 4.1521.

3.2.6 2-(7-(4-bromophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AHPI-Br)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 202–212 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.68 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (dd, J = 17.1, 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.61 – 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.40 – 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (dd, J = 12.1, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.06 (s), 148.56 (s), 145.26 (s), 137.51 (s), 133.82 (s), 131.73 (s), 130.33 (s), 129.65 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 128.45 (s), 128.11 (s), 127.74 (s), 127.23 (d, J = 2.7 Hz), 126.38 (s), 125.98 (s), 123.69 (s), 121.53 (s), 119.32 (s), 118.44 (s), 118.11 (s), 113.58 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H15BrN2O: 438.04; found: 440 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C25H15BrN2O: C, 68.35; H, 3.44; Br, 18.19; N, 6.38; O, 3.64; found: C, 68.2480; H, 3.3396; N, 6.4046; 3.2327.

3.2.7 2-(7-(4-iodophenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AHPI-I)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 225–229 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.66 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 8.0, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (dd, J = 8.1, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.38 – 7.27 (m, 3H), 7.23 – 7.14 (m, 1H), 7.07 (dd, J = 10.3, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.04 (s), 148.50 (s), 145.29 (s), 139.76 (s), 138.06 (d,J = 19.8 Hz), 131.72 (s), 130.32 (s), 129.63 (d,J = 7.5 Hz), 128.59 (s), 128.10 (s), 127.73 (s), 127.23 (s), 126.37 (s), 126.02 (s), 121.57 (s), 119.34 (s), 118.44 (s), 118.10 (s), 113.58 (s), 95.13 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C25H15IN2O: 488.03; found: 487 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C25H15IN2O: C, 61.74; H, 3.11; I, 26.10; N, 5.76; O, 3.29; found: C, 60.8052; H, 3.3026; N, 5.8802; O, 3.1908.

3.2.8 4-(8-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-7-yl)phenethyl acetate (AHPI- EtOAc)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 147–150 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.87 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.61 – 7.41 (m, 5H), 7.39 – 7.28 (m, 1H), 7.21 – 6.97 (m, 3H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.93 (s), 157.90 (s), 148.47 (s), 144.74 (s), 139.68 (s), 138.16 (s), 136.71 (s), 131.62 (s), 130.79 (s), 129.90 (s), 129.54 (d, J = 10.1 Hz), 127.86 (s), 127.36 (s), 127.27 – 126.31 (m), 125.77 (s), 121.15 (s), 119.11 (s), 118.05 (s), 117.77 (s), 113.68 (s), 77.45 (s), 77.03 (s), 76.61 (s), 64.36 (s), 34.89 (s), 20.93 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C29H24N2O3: 446.16; found: 447 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C29H24N2O3: C, 78.01; H, 4.97; N, 6.27; O, 10.75; found: C, 78.4048; H, 4.8514; N, 7.0181; O, 8.0108.

3.2.9 4-methoxy-2-(7-phenyl-7H-acenaphtho[1,2-d]imidazol-8-yl)phenol (AMHPI)

Orange crystalline solid. Melting Range: 162–165 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 12.39 (s, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (dq, J = 15.2, 8.2 Hz, 8H), 7.36 – 7.27 (m, 1H), 7.04 – 6.95 (m, 2H), 6.75 (dd, J = 8.9, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.32 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 3.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 152.21 (s), 151.39 (s), 148.52 (s), 145.05 (s), 138.42 (d, J = 17.3 Hz), 131.84 (s), 130.59 (s), 129.72 (d, J = 10.8 Hz), 128.04 (s), 127.54 (s), 127.12 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 126.56 (s), 121.35 (s), 119.28 (s), 118.63 (s), 117.65 (s), 113.33 (s), 109.65 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.80 (s), 55.23 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C26H18N2O2: 390.14; found: 390 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C26H18N2O2: C, 79.98; H, 4.65; N, 7.17; O, 8.20; found: C, 79.89; H, 4.5840; N, 7.0847; O, 8.1018.

3.2.10 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazole (BTPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 225–227 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.60 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (s, 2H), F 7.31 – 7.18 (m, 9H), 7.16 – 7.10 (m, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 6.98 – 6.91 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 163.85 (s), 160.47 (s), 147.22 (s), 138.55 (s), 134.48 (s), 133.34 (s), 131.31 (s), 131.03 (s), 130.44 (dd, J = 25.5, 9.8 Hz), 129.16 (s), 128.81 – 128.07 (m), 127.55 (s), 126.89 (s), 116.48 (s), 116.18 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H19FN2: 390.15; found: 390 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H19FN2: C, 83.05; H, 4.90; F, 4.87; N, 7.17; found: C, 83.48; H, 5.08; N, 7.19.

3.2.11 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazole (BOMPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 210–214 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.60 (dd, J = 15.9, 8.5 Hz, 4H), 7.33 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.26 – 7.16 (m, 9H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (dt, J = 17.0, 8.2 Hz, 7H), 6.69 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 3.38 (s, 5H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.02 (s), 145.78 (s), 138.37 (s), 134.66 (s), 133.54 (s), 132.67 (s), 131.49 – 130.78 (m), 129.81 (s), 129.23 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 128.67 (s), 128.20 (d, J = 10.6 Hz), 127.70 (s), 126.69 (s), 120.92 (s), 120.33 (s), 115.41 (s), 115.11 (s), 110.71 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s), 54.85 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C28H21FN2O: 420.16; found for: 420. [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C28H21FN2O: C, 79.98; H, 5.03; F, 4.52; N, 6.66; O, 3.81; found: C, 80.43; H, 5.28; N, 6.63; O, 4.83. Melting Range: 210–214 °C.

3.2.12 2-(1,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (BHPI)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 249–255 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.47 (s, 1H), 7.58 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.42 – 7.35 (m, 3H), 7.28 (s, 2H), 7.25 – 7.22 (m, 3H), 7.22 – 7.17 (m, 3H), 7.16 – 7.11 (m, 3H), 7.10 – 7.04 (m, 1H), 6.57 – 6.50 (m, 1H), 6.50 – 6.42 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.64 (s), 145.12 (s), 137.34 (s), 135.37 (s), 133.30 (s), 131.53 (s), 130.65 (s), 130.37 – 129.55 (m), 129.39 (s), 129.12 – 128.24 (m), 127.16 (d, J = 7.5 Hz), 126.22 (s), 117.98 (d, J = 15.7 Hz), 113.19 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H20N2O: 388.16; found: 388 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H20N2O: C, 83.48; H, 5.19; N, 7.21; O, 4.12 found: C, 84.10; H, 5.36; N, 7.23; O, 3.97.

3.2.13 2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (BHPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 217–220 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.38 (s, 3H), 7.52 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 7H), 7.22 (dd, J = 14.0, 7.2 Hz, 21H), 7.18 – 7.07 (m, 20H), 7.07 – 6.98 (m, 8H), 6.57 – 6.43 (m, 7H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.30 (s), 160.99 (s), 158.65 (s), 145.20 (s), 135.47 (s), 133.24 (d, J = 18.1 Hz), 131.51 (s), 130.60 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 130.26 (s), 129.84 (s), 128.80 (s), 128.49 (s), 127.16 (d, J = 18.1 Hz), 126.03 (s), 118.07 (d, J = 13.9 Hz), 117.03 (s), 116.72 (s), 113.00 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H19FN2O: 406.15; found: 407 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H19FN2O: C, 79.79; H, 4.71; F, 4.67; N, 6.89; O, 3.94; found: C,79.7581; H, 4.7778; N, 6.9205; O, 3.8991.

3.2.14 2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (BHPI-Cl)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 201–203 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.28 (s, 4H), 7.56 – 7.48 (m, 9H), 7.34 (s, 4H), 7.31 (s, 6H), 7.28 (s, 8H), 7.25 (s, 8H), 7.22 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 11H), 7.17 – 7.03 (m, 26H), 6.59 – 6.46 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.61 (s), 145.12 (s), 135.79 (d, J = 15.8 Hz), 135.34 (s), 133.08 (s), 130.25 (dd, J = 25.0, 7.9 Hz), 129.76 (s), 128.87 (s), 128.51 (s), 127.21 (d, J = 18.3 Hz), 126.15 (s), 118.13 (d, J = 17.1 Hz), 112.94 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.80 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H19ClN2O: 422.12; found: 423 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H19ClN2O: C, 76.68; H, 4.53; Cl, 8.38; N, 6.62; O, 3.78; found: C, 76.5001; H, 4.6113; N, 6.7546; O, 3.6899.

3.2.15 2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (BHPI-Br)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 217–222 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.25 (s, 3H), 7.50 (dd, J = 11.0, 8.0 Hz, 14H), 7.35 – 7.18 (m, 22H), 7.17 – 7.07 (m, 12H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 8H), 6.52 (q, J = 8.1 Hz, 7H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.60 (s), 145.07 (s), 136.41 (s), 135.73 (s), 133.06 (s), 131.51 (s), 130.39 (t, J = 3.7 Hz), 129.73 (s), 128.89 (s), 128.51 (s), 127.22 (d, J = 18.3 Hz), 126.18 (s), 123.41 (s), 118.14 (d, J = 18.3 Hz), 112.92 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H19BrN2O: 466.07; found: 467 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H19BrN2O: C, 69.39; H, 4.10; Br, 17.10; N, 5.99; O, 3.42; found: C, 69.3942; H, 4.2815; N, 6.0235; O, 3.3812.

3.2.16 2-(1-(4-iodophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)phenol (BHPI-I)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 207–210 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.24 (s, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (dq, J = 13.8, 6.8 Hz, 7H), 7.12 (ddd, J = 12.9, 9.9, 7.5 Hz, 4H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.59 – 6.48 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.59 (s), 145.05 (s), 139.04 (s), 137.12 (s), 135.77 (s), 133.09 (s), 131.52 (s), 130.78 – 130.21 (m), 129.75 (s), 128.91 (s), 128.51 (s), 127.24 (d, J = 16.7 Hz), 126.23 (s), 118.16 (d, J = 19.3 Hz), 112.94 (s), 94.98 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H19IN2O: 514.05; found: 515 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H19IN2O: C, 63.05; H, 3.72; I, 24.67; N, 5.45; O, 3.11; found: C, 69.3942; H, 4.2815; N, 6.0235; O, 3.6832.

3.2.17 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole (PTPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 231–233 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.87 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.78 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 8.71 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.78 – 7.71 (m, 2H), 7.70 – 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.60 – 7.45 (m, 10H), 7.36 – 7.27 (m, 10H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.77 (s), 161.45 (s), 151.30 (s), 137.60 (s), 134.89 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 131.07 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 130.51 (s), 129.56 (d, J = 13.1 Hz), 129.16 (s), 128.63 – 128.09 (m), 127.43 (d, J = 14.7 Hz), 126.52 (s), 125.89 (s), 125.17 (s), 124.39 (s), 123.44 – 122.79 (m), 120.79 (s), 117.53 (s), 117.22 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H17FN2: 388.14; found: 388 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H17FN2: C, 83.49; H, 4.41; F, 4.89; N, 7.21; found: C, 83.74; H, 4.60; N, 7.19.

3.2.18 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole (POMPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 210–214 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.71 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.68 – 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J = 8.1, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.45 – 7.26 (m, 5H), 7.12 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.63 (s), 150.23 (s), 137.65 (s), 134.42 (s), 132.65 (s), 131.53 (s), 130.51 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 129.35 (s), 128.31 (s), 127.51 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 126.42 (s), 125.67 (s), 125.08 (s), 124.35 (s), 123.40 – 122.88 (m), 120.80 (d, J = 18.5 Hz), 120.13 (s), 116.36 (s), 116.06 (s), 110.68 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s), 55.10 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C28H19FN2O: 418.15; found: 418 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C28H19FN2O: C, 80.37; H, 4.58; F, 4.54; N, 6.69; O, 3.82; found: C, 80.76; H, 4.82; N, 6.68; O, 4.87.

3.2.19 2-(1-phenyl-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol (PHPI)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 192–194 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.87 (s, 3H), 8.76 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 4H), 8.73 – 8.65 (m, 8H), 7.81 – 7.71 (m, 15H), 7.71 – 7.66 (m, 5H), 7.63 (ddd, J = 6.5, 3.9, 1.5 Hz, 9H), 7.51 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.0, 1.3 Hz, 4H), 7.27 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.25 – 7.17 (m, 7H), 7.13 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.3 Hz, 4H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.8 Hz, 4H), 6.73 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.5 Hz, 4H), 6.54 – 6.46 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.40 (s), 148.60 (s), 139.24 (s), 134.58 (s), 131.19 – 130.55 (m), 129.64 (s), 129.25 (s), 128.61 (s), 127.67 (s), 127.21 (s), 126.70 (s), 126.24 (s), 125.96 (s), 125.43 (s), 124.35 (s), 123.38 (s), 122.75 (s), 121.04 (s), 118.23 (s), 113.29 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H18N2O: 386.14; found: 386 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H18N2O: C, 83.92; H, 4.69; N, 7.25; O, 4.14; found: C, 83.24; H, 5.30; N, 6.81; O, 4.89.

3.2.20 2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol (PHPI-F)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 187–189 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.73 (s, 1H), 8.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.68 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.66 – 7.48 (m, 3H), 7.41 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.32 (s), 161.98 (s), 159.38 (s), 148.69 (s), 135.21 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 134.64 (s), 131.45 – 130.92 (m), 129.68 (s), 128.60 (s), 127.73 (s), 127.14 (s), 126.79 (s), 126.58 – 125.73 (m), 125.54 (s), 124.46 (s), 123.37 (s), 122.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 120.78 (s), 118.35 (s), 118.05 (s), 113.11 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H17FN2O: 404.13; found: 404 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd. for C27H17FN2O: C, 80.18; H, 4.24; F, 4.70; N, 6.93; O, 3.96; found: C, 80.39; H, 4.40; N, 6.87; O, 4.96.

3.2.21 2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol (PHPI-Cl)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 200–204 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.68 (s, 1H), 8.76 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.69 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.81 – 7.63 (m, 4H), 7.61 – 7.47 (m, 3H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.24 – 7.18 (m, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 18.0, 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.62 – 6.50 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.33 (s), 148.55 (s), 137.73 (s), 136.83 (s), 134.73 (s), 131.20 (d, J = 18.5 Hz), 130.64 (s), 129.66 (s), 128.59 (s), 127.72 (s), 126.93 (d, J = 14.8 Hz), 126.23 (d, J = 17.5 Hz), 125.70 (d, J = 19.5 Hz), 124.46 (s), 123.36 (s), 122.64 (d, J = 14.9 Hz), 120.78 (s), 118.37 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 113.03 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H17ClN2O: 420.10; found: 420 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd for C27H17ClN2O: C, 77.05; H, 4.07; Cl, 8.42; N, 6.66; O, 3.80; found: C, 77.05; H, 4.10; N, 6.58; O, 4.05.

3.2.22 2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol (PHPI-Br)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 211–212 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.63 (s, 1H), 8.72 (dd, J = 22.5, 8.4 Hz, 3H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (dt, J = 15.3, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (dd, J = 16.5, 7.9 Hz, 3H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 16.7, 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.37 (s), 148.59 (s), 138.33 (s), 134.85 (s), 134.38 (s), 131.05 (d, J = 12.1 Hz), 129.75 (s), 128.67 (s), 127.79 (s), 126.98 (d, J = 11.8 Hz), 126.62 – 125.78 (m), 125.63 (s), 124.94 (s), 124.52 (s), 123.41 (s), 122.71 (d, J = 15.3 Hz), 120.86 (s), 118.40 (s), 113.08 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.80 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H17BrN2O: 464.05; found: 465 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd for C27H17BrN2O: C, 69.69; H, 3.68; Br, 17.17; N, 6.02; O, 3.44; found: C, 69.9066; H, 3.6637; N, 6.3926; O, 3.5286.

3.2.23 2-(1-(4-iodophenyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazol-2-yl)phenol (PHPI-I)

White crystalline solid. Melting Range: 223–226 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 13.63 (s, 1H), 8.70 (dd, J = 22.3, 8.4 Hz, 3H), 8.04 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (dt, J = 25.3, 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (dd, J = 12.9, 8.2 Hz, 3H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 16.6, 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.35 (s), 148.53 (s), 140.34 (s), 139.00 (s), 134.84 (s), 131.11 (s), 129.71 (s), 127.77 (s), 126.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 126.29 (d, J = 15.2 Hz), 125.88 (s), 125.61 (s), 124.49 (s), 123.40 (s), 122.69 (d, J = 15.4 Hz), 120.86 (s), 118.41 (d, J = 4.7 Hz), 113.07 (s), 96.47 (s), 77.65 (s), 77.23 (s), 76.81 (s). MS (EI) calcd. for C27H17IN2O: 512.04; found: 513 [M+]. Elemental analysis calcd for C27H17IN2O: C, 63.30; H, 3.34; I, 24.77; N, 5.47; O, 3.12; found: C, 62.0275; H, 3.3624; N, 5.5396; O, 3.2086.

3.3 Photophysical properties

Absorption and photoluminescence emission spectra were obtained from Scinco (S-4100 model) UV–vis spectrometer and Scinco (FS2 model) fluorescence spectrophotometer respectively. The fluorescence spectra were corrected for the instrumental response. The quantum yields were calculated by measuring the integrated area under the emission curve and by using following equation (1): Where ‘Φ’ is the quantum yield, ‘I’, the integrated emission intensity, ‘OD’, the optical density at the excitation wavelength, and ‘η’ is the refractive index of the solvent. The subscript ‘standard’ and ‘sample’ refer to the fluorophore of reference and unknown, respectively. In this case, the unknown is all the imidazole molecules displayed in scheme and the reference is quinine sulfate (Φf = 0.54 in 0.1 M H2SO4). Optically matched solutions with very similar optical densities of the “sample’ and “standard” at a given absorbing wavelength were used for quantum yield calculations.

3.4 Computational studies

In the present work, the theoretical investigation of the all the electronic structure calculations and geometrical properties was performed with the Gaussian 09 package (Frisch et al., 2009). The geometry optimization of the π-expanded phenanthro[9,10-d], π-fused acenaphtho[1,2-d], and π-non fused tetra-substituted imidazoles were performed using the DFT method, and the electronically excited state was performed depending on Self Consistent Field-Time Dependent-DFT (SCF-TD-DFT) method using Becke’s three-parameter hybrid exchange functional (Becke, 1993) and Lee, and Yang and Parr correlation functional (Lee et al., 1988) B3LYP/6-31G (d, p). The spin density distributions were visualized using Gaussview 5.0.8.

3.5 Urease inhibition assay

The Jack bean urease activity was determined by measuring the amount of ammonia produced with the indophenols method described by Weatherburn et. al. The reaction mixtures, comprising 20 µL of the enzyme (Jack bean urease, 5 U/mL) and 20 μL of compounds in 50 μL buffer (100 mM urea, 0.01 M K2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.01 M LiCl, pH 8.2), were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in 96-well plate. Briefly, 50 μL each of phenol reagents (1%, w/v phenol and 0.005%, w/v sodium nitroprusside) and 50 μL of alkali reagent (0.5%, w/v NaOH and 0.1% Sodium hypochlorite NaOCl) were added to each well. The absorbance at 625 nm was measured after 10 min, using a microplate reader (OPTI Max, Tunable). All reactions were performed in triplicate. The urease inhibition activities were calculated according to the following formula (2): Where ODcontrol and ODsample represent the optical densities in the absence and presence of the sample, respectively. Thiourea was used as the standard inhibitor for urease.

3.6 Kinetic mechanism study

Kinetic analysis was carried out to determine the mode of inhibition. The two inhibitors (AHPI-Br and POMPI-F) were selected based on the most potent IC50 values. Kinetics was carried out by varying the concentration of urea in the presence of different concentrations of compound AHPI-Br (0.00, 0.0145, and 0.029 µM) compound POMPI-F (0.00, 0.0145, and 0.029 µM). In detail, the urea concentration was changed from 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.125 mM for urease kinetics studies and the remaining procedure were kept the same for all kinetic studies as described in urease inhibition assay protocol. Maximal initial velocities were determined from the initial linear portion of absorbance up to 10 min after the addition of enzyme at per minute’s interval. The inhibition type on the enzyme was assayed by the Lineweaver-Burk plot of inverse of velocities (1/V) versus the inverse of substrate concentration 1/[S] mM−1. The EI dissociation constant Ki was determined by a secondary plot of 1/V versus inhibitor concentration and ESI dissociation constant Kiʹ was calculated by intercept versus inhibitors concentrations. Urease activity was determined by measuring ammonia production using the indophenol method as reported previously (Saeed et al., 2015). The results (change in absorbance per min) were processed by using SoftMaxPro.

3.7 Molecular docking

3.7.1 Preparation of ligands receptors

The structural files of desired ligands PHPI, PHPI-Cl, AHPI-Br, and POMPI-F were retrieved from NCBI-PubChem in.sdf format and they were stored as.pdb after changing the structural file format. These ligands were imported and processed as ligands using ligand processing in the AutoDockTools-1.5.7. The final processed ligands were stored as.pdbqt for docking studies. The 3D structures of Bcl-2 (PDB ID: 6QGH), Bcl-xl (PDB ID: 1R2D), and Urease (PDB ID: 4H9M) were retrieved from RCSB-Protein Data Bank. Each protein structure was observed, co-crystal ligands and heteroatoms were removed, missing residues and H-atoms were added, and the structure was saved as.pdb format. The structure was further optimized for energy minimization using Chimera-UCSF tool using algorithm steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient for 100 cycles each. The optimized models were checked for any sort of visual distortion in the main chain, side chains, and loops on the Discovery studio visualizer. The quality check of the optimized structure was performed on the SAVES server. Prior to docking of selected receptors, the docking program was validated by re-docking of co-crystal ligand allowing RMSD of 2 Å as cut-off criteria. The optimized receptor structures were imported to AutoDockTools-1.5.7 for generating the binding grids. The following coordinates were used for generating binding grids: (i) for Bcl- xl × = 23.104, y = 7.353, and z = 74.408(Azam et al., 2014; Bekker et al., 2021); for Bcl-2 × = -0.137, y = -5.074, and z = 12.452(Katz et al., 2008; Kirubhanand et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2011); and for Urease × = 1.511, y = -55.461, and z = -26.593(Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020), (Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020) (Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020) (Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020) (Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020) (Rashid et al., 2020; Sultan et al., 2020). Kollman and Gasteiger(-Marsili) charges were added to respective proteins in.pdbqt format. Selection of the docking sites for each protein was selected as per literature reviews and grid box with desired configurations (in respective config.txt form) were prepared (Ahmed and Jami, 2012; Gurudutta et al., 2005; Rashid et al., 2020; Saxena et al., 2013; Sultan et al., 2020). The processed structures were stored as.pdbqt files for docking purposes.

3.7.2 Molecular docking studies

The molecular docking of ligands with receptor was done using Autodock vina v.1.2.0. that was run from the command line with configuration of grid point spacing = 0.375 Å. The exhaustiveness value of the docking was 8. The cut-off limits for the RMSD were considered as 2 Å. The output files obtained were analysed visually using Discovery studio visualizer 2019 Client. The 2-D and 3-D images illustrating the best interaction were snapped.

3.8 Anti-proliferative activity

The anti-proliferative activity of synthesized imidazole derivatives against the human stomach cancer cell (AGS) were evaluated using an MTT assay as our previous study [75,76]. 2 × 104 cells per well were plated in a 96 well plates containing 100 μL of the complete culture medium. Next day, the test compounds of different concentration were added onto 96 well plates. The final concentration of DMSO Hybri-Max in all assays was less than 0.1%. 100 μL MTT reagent was added to each well and then incubated for 3 h. MTT solution was removed and 200 μL DMSO was added to each well. The DMSO solution is used as a negative control. The optical density values were recorded using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at a 560 nm and 670 nm respectively. Blank values were subtracted from experimental values. The morphological observation of both treated and untreated AGS cell lines was observed through by Leica light microscope DM2000 (Wetzlar, Germany).

3.9 Apoptotic cell death detection

As per previous study by Balusamy et al., [75, 76] hoechst and propidium iodide staining analysis were performed. The cells 5 × 104/well of AGS cells were seeded and apoptosis induction was measured as stated. The selected compounds from significant IC50 value such as, PHPI-Cl and PHPI-I at different concentration (25 and 50 μg/ml) were used to analyze apoptotic cell death detection. Control wells were treated only 0.1% DMSO. Fluorescent image of AGS cells which was involved in apoptotic cell death analysis was identified by Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

3.10 ADME drug likeness studies

SwissADME online web server ( http://www.swissadme.ch) was used for in-silico analysis of toxicity and pharmacokinetic properties of the potential compounds. The 2D chemical structure and SMILES formats of each compound were uploaded and program weas run for the analysis. The one output panels on the web server provides a compilation of parametric values related to physicochemical properties, lipophilicity, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry for each compound was observed (Daina et al., 2017).

4 Conclusion

In summary, a series of tetra-substituted imidazole derivatives were designed, synthesized, studied their photo physical and biological activities. Among that PHP-I and PHPI-CI showed excellent anti-cancer activity in vitro that was re-confirmed by molecular docking studies. PHP-I and PHPI-CI has the ability to inhibit the growth of AGS cells by initiating apoptosis mediated cell death. Whereas, AHPI-Br and POMPI-F showed urease inhibitory activity in vitro and docking with the jack bean urease protein further confirms in vitro results. We believe that these compounds can be a potential target for cancer and capable of inhibiting urease enzyme, therefore recommended to test in vivo, that aids further use in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A2C1008375 and No. 2020R1F1A1050024).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- BCL-2 as target for molecular docking of some neoplastic drugs. Open Access Sci. Reports. 2012;1:458.

- [Google Scholar]

- An abnormally slow proton transfer reaction in a simple HBO derivative due to ultrafast intramolecular-charge transfer events. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2015;17:16257-16269.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Imidazole as a promising medicinal scaffold: current status and future direction. Drug Des. Devel. Ther.. 2021;15:3289-3312.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of unique binding site and molecular docking studies for structurally diverse Bcl-xL inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res.. 2014;23:3765-3783.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys.. 1993;98:5648-5652.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cryptic-site binding mechanism of medium-sized Bcl-xL inhibiting compounds elucidated by McMD-based dynamic docking simulations. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:5046.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of immunologic and intestinal effects in rats administered an E 171-containing diet, a food grade titanium dioxide (TiO2) Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2019;133:110793

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neutrophil–macrophage cooperation and its impact on tissue repair. Immunol. Cell Biol.. 2019;97:289-298.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of imidazolpyrazole ligands as potent urease inhibitors: Synthesis, Antiurease, and in silico docking studies. ChemistrySelect.. 2020;5(38):11817-11821.

- [Google Scholar]

- Living donor liver transplantation: The Asian perspective. Transplantation. 2014;97

- [Google Scholar]

- Excited state prototropic activities in 2-hydroxy 1-naphthaldehyde. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:83-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:42717.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel Imidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]triazines and their derivatives as focal adhesion kinase inhibitors with antitumor activity. J. Med. Chem.. 2015;58:237-251.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and applications of 2-substituted Imidazole and its derivatives: A review. J. Heterocycl. Chem.. 2019;56:2299-2317.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potent, orally absorbed glucagon receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 1999;9:641-646.

- [Google Scholar]

- An efficient green protocol for the synthesis of 1{,}2{,}4{,}5-tetrasubstituted imidazoles in the presence of ZSM-11 zeolite as a reusable catalyst. RSC Adv.. 2022;12:4358-4369.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrafast hydrogen bonding dynamics and proton transfer processes in the condensed phase. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

- New therapeutic agents in thrombosis and thrombolysis. CRC Press; 2016.

- Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G.A., 2009. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford, CT 32, 5648–5652.

- Structural conservation of residues in BH1 and BH2 domains of Bcl-2 family proteins. FEBS Lett.. 2005;579:3503-3507.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, photophysical and electrochemical properties of polyimides of tetraaryl imidazole. Polym. Bull.. 2018;75:93-107.