Translate this page into:

Synthesis, biological evaluation and network pharmacology based studies of 1,3,4-oxadiazole bearing azaphenols as anticancer agents

⁎Corresponding authors at: College of Pharmacy, Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang 550025, China. yangwude476@gzy.edu.cn (Wude Yang), yuxiang@gzy.edu.cn (Xiang Yu)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

To discover novel and effective potential anticancer agents, a series of azophenol derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety was synthesized and investigated for their anticancer activities against several human cancer cell lines by MTT method. Their structures were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and HRMS spectral analyses. Among the prepared compounds, 5df displayed significant anti-proliferative activity against HCT116 cancer cells with an IC50 value of 4.09 ± 0.04 µM. Moreover, this compound had low cytotoxicity against normal cells. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that compound 5df arrested the cell cycle at S phase and induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, network pharmacology analysis calculated that 5df might target several key proteins, including AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (AKT1), SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase (SRC). Furthermore, molecular docking study indicated that 5df exhibited potentially high binding affinity to these target proteins with binding energies lower than −8 kcal/mol. These findings provide valuable insights for the development of azophenol derivatives as potential anticancer agents.

Keywords

Azophenol

1,3,4-Oxadiazole

Anticancer activity

Network pharmacology

Molecular docking

1 Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in the twenty-first century and a critical challenge that needs to be addressed to increase human life expectancy (Bray et al., 2018). Recent statistics revealed a staggering 19.3 million new cancer cases and nearly ten million cancer-related deaths in 2020 (Sung et al., 2011). Colorectal cancer ranks as the third most prevalent cancer globally and the second deadliest in terms of mortality rate (Sawicki et al., 2021). The emergence and progression of colorectal cancer result from a complex interplay of factors, including age, family history, gender, geographical location, and personal medical history (Peng et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2018). Conventional treatment approaches for colorectal cancer encompass surgical intervention and chemotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents induce DNA damage or activate diverse signaling pathways to prompt cancer cell demise, including cell cycle arrest, inhibition of global translation, blockage of DNA repair, and other mechanisms (Woods and Turchi, 2013). Hence, the discovery and advancement of novel chemical entities that are more efficacious and less toxic would signify a groundbreaking stride in cancer research.

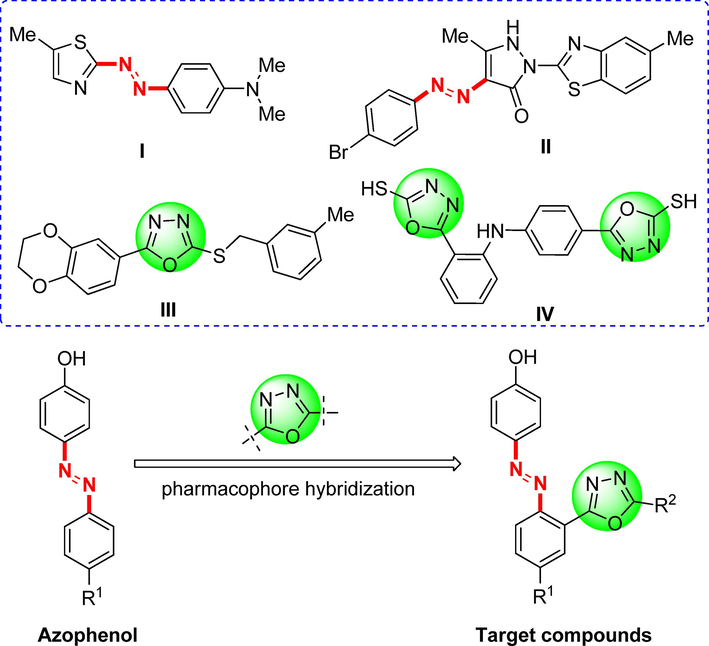

Azo derivatives, characterized by their nitrogen-nitrogen double bond (—N⚌N—), rank among the most crucial chromophores and find diverse applications in the realms of science, industry, and pharmaceuticals (Benkhaya et al., 2020; Tahir et al., 2021). Presently, the synthesis of azo derivatives has attracted significant attention due to their varied bioactivities, such as antibacterial (Atay et al., 2017), antioxidant (Mohammadi et al., 2015), antifungal (Matada et al., 2020), anti-inflammatory (Manjunatha and Bodke, 2021), and antitubercular (Manjunatha et al., 2021). Furthermore, azo derivatives also displayed substantial anticancer potentials. For example, Keshavayya et al. reported a robust anticancer heterocyclic azo derivative, dimethyl-[4-(5-methyl-thiazol-2-ylazo)-phenyl]-amine (I, Fig. 1), which manifested potent anticancer effects against A-549 and K-562 cell lines (Ravi et al., 2020). Another novel azo derivative, II (Fig. 1), exhibited notable activity against the human colon cell line (HCT116) by inhibiting the growth of the cancerous cells (Maliyappa et al., 2020).

Design of the azophenol derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety.

On the other hand, 1,3,4-oxadiazole stands as a widely studied pharmacophore that has garnered significant research attention in recent years, owing to its metabolic characteristics and capacity to establish hydrogen bonds with receptor sites. These compounds serve as excellent bioisosteres of amides and esters, as the incorporation of the oxadiazole core with the azole (—N⚌C—O—) motif enhances lipophilicity. This property plays a pivotal role in facilitating the transmembrane diffusion of drugs, enabling them to effectively reach their intended targets (Bajaj et al., 2015; Andreani et al., 2001). These molecules exhibit diverse biological activities, including anti-inflammatory (Abd-Ellah et al., 2017), antidiabetic (Shingalapur et al., 2010), antianxiety (Harfenist et al., 1996), antifungal (Wang et al., 2021), antibacterial (Guo et al., 2019) and antitubercular etc (Ahsan et al., 2011). Notably, numerous distinct 1,3,4-oxadiazoles also displayed substantial anticancer properties against various cancer cell lines. For instance, compounds III and IV (Fig. 1) have demonstrated potent anticancer activities (Zhang et al., 2011; Abou-Seri, 2010).

The development of small molecules through molecular hybridization from known structural motifs is one of the current trends in drug discovery. It is anticipated that improved cytotoxicity may be achieved through the structural conjugation of two potent pharmacophoric units. However, there are few literature reports on the combination of azo group and 1,3,4-oxadiazole for the development of anti-tumor drug molecules. Drawing inspiration from the aforementioned facts and our prior research (Yu et al., 2021, 2023), we devised and synthesized a novel series of azophenol derivatives containing the 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety (Fig. 1) as potential anticancer agents. The in vitro anticancer activities of all target derivatives were evaluated via the MTT method against several human cancer cell lines, including lung cancer cells (A549), cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), colon cancer cells (HCT116), hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HePG2), breast cancer cells (MCF-7), HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells (HT1080). The mechanism of antiproliferative effects of this class of compounds was studied via cell cycle arrest and cell apoptosis assay. Additionally, network pharmacology and molecular docking study were conducted to identify potential targets of these derivatives. This study may provide lead molecules for the discovery and development of anticancer candidates.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemistry

All reagents and solvents were of reagent grade or purified according to standard methods before use. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed with silica gel plates using silica gel 60 GF254 (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). Melting points were determined on an X-5A micro melting point tester (Gongyi Kerui instrument Co., Ltd.) and were uncorrected. Infrared absorption spectra (IR) were recorded by IRTracer-100 (Shimadzu, Wikipedia, Japan). 1H/13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance neo 400 or 600 MHz instrument (Bruker, Bremerhaven, Germany) in CDCl3 or DMSO‑d6 using TMS (tetramethylsilane) as the internal standard. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was determined by a Xevo G2-SQTOF instrument (Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

2.1.1 General procedure for the synthesis of (E)-N'-(2-nitrobenzylidene)arylhydrazides (2aa ∼ eg)

To a solution of 2-nitrobenzaldehydes (1a ∼ e, 1 mmol) and aryl hydrazides (1 mmol) in ethanol (EtOH, 10 mL), two drops of acetic acid (HOAc) was added, and the mixture was reflux for 1–5 h. When the reaction was complete, the mixture was cooled to room temperature until no more precipitate was observed. Then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give the intermediates (2aa ∼ eg). The compounds were not purified and went straight to the next step.

2.1.2 General procedure for the synthesis of 2-(2-nitrophenyl)-5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles (3aa ∼ eg)

The intermediates 3aa ∼ eg (1.1 mmol), K2CO3 (3.0 mmol, 414.6 mg) and iodine (1.1 mmol, 279.4 mg) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 10 mL), then the reaction mixture was stirred at 100 °C. When the reaction was complete according to TLC analysis, the mixture was treated with saturated Na2S2O3 (20 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc, 3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine (3 × 20 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated. The given residues were purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to get the compounds 3aa ∼ eg in 61–98 % yields. Their spectral data were provided in Supplementary Material.

2.1.3 General procedure for the synthesis of 2-(5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)anilines (4aa ∼ eg)

A mixture of compounds 3aa ∼ eg (1 mmol), hydrated tin(II) chloride (5 mmol, 1128.5 mg) in EtOAc (10 mL) was reflux for 4-12 h. While the reaction was complete, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and adjusted to pH 8–9 with saturated NaHCO3. Then the mixture was filtered and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 50 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with saturated brine (100 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated, and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to obtain compounds 4aa ∼ eg in 48–93 % yields. Their spectral data were provided in Supplementary Material.

2.1.4 General procedure for the synthesis of (E)-4-((2-(5-aryl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl) phenol derivatives (5aa ∼ eg)

To a mixture of compounds 4aa ∼ eg (1 mmol), water (6 mL) and concentrated HCl (12 mol/L, 0.5 mL) at 0 °C, a solution of sodium nitrite (NaNO2, 1.2 mmol) in water (6 mL) was added dropwise while maintaining the temperature below 5 °C. After stirring for 0.5–1 h, a solution of diazonium chloride was prepared. Subsequently, The solution of diazonium chloride was added gradually to a mixture of phenol (1.1 mmol), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 2 mmol), EtOH (10 mL) and water (10 mL) at 0–5 °C. After the addition of the above diazonium solution, the mixture was continued to stir for 4–6 h until a lot of precipitate was produced. The solid was collected, washed with water (3 × 10 mL), dried and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to afford the target products 5aa ∼ eg in 38–90 % yields. The spectroscopic and analytical data of these compounds are as follows:

2.1.4.1 (E)-4-((2-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5aa)

Yield: 48 %, Red solid, M.p.: 281–283 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1606, 1510, 1369, 1246, 1141, 837, 704; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.50 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.85 – 7.78 (m, 3H), 7.74 – 7.70 (m, 2H), 7.68 – 7.59 (m, 3H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.3, 163.0, 161.2, 149.9, 145.2, 132.4, 131.7, 129.9 × 2, 129.1 × 2, 126.2 × 2, 125.1 × 2, 122.9, 120.4, 116.6, 115.6 × 2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C20H14N4O2Na ([M + Na]+) 365.1008, found 365.1002.

2.1.4.2 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ab)

Yield: 89 %, Red solid, M.p.: 273–275 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1589, 1498, 1384, 1284, 1143, 1095, 837, 731; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.45 (s, 1H), 8.19 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.09 – 8.07 (m, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.80 – 7.77 (m, 1H), 7.73 – 7.70 (m, 2H), 7.47 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.4, 163.9, 163.3, 162.7, 161.6, 150.3, 145.6, 132.7, 130.3, 130.2, 129.3, 125.5 × 2, 120.8, 120.0, 117.0, 116.8, 116.6, 116.0 × 2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C20H13FN4O2Na ([M + Na]+) 383.0914, found 383.0909.

2.1.4.3 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ac)

Yield: 73 %, Red solid, M.p.: 238–239 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1591, 1463, 1382, 1286, 1143, 835,754, 731; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.47 (s, 1H), 8.19 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.78 – 7.77 (m, 1H), 7.73 – 7.67 (m, 4H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.5, 163.1, 161.2, 149.9, 145.2, 136.4, 132.4, 129.9, 129.8, 129.2 × 2, 127.9 × 2, 125.1 × 2, 121.8, 120.3, 116.6, 115.6 × 2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C20H13ClN4O2Na ([M + Na]+) 399.0619, found 399.0613.

2.1.4.4 (E)-4-((2-(5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ad)

Yield: 38 %, Red solid, M.p.: 214–216 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1587, 1508, 1313, 1282, 1143, 842, 725; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.47 (s, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.83 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.79 – 7.77 (m, 2H), 7.72 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.49 – 7.44 (m, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.8, 163.3, 161.6, 150.3, 145.6, 138.9, 132.8, 132.7, 130.2, 130.1, 129.3, 126.8, 125.5 × 2, 123.7, 123.2, 120.6, 117.0, 116.0 × 2, 20.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H16N4O2Na ([M + Na]+) 379.1165, found 379.1159.

2.1.4.5 (E)-4-((2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ae)

Yield: 89 %, Red solid, M.p.: 253–255 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1508, 1327, 1278, 1143, 854, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.50 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.75 – 7.68 (m, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.55 – 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.22 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.6, 163.4, 161.6, 159.7, 150.3, 145.6, 132.8, 130.7, 130.3, 130.2, 125.5 × 2, 124.5, 120.7, 118.8, 118.1, 117.0, 116.0 × 2, 111.2, 55.33; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H16N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 395.1114, found 395.1105.

2.1.4.6 (E)-4-((2-(5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5af)

Yield: 69 %, Red solid, M.p.: 289–291 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1591, 1504, 1386, 1286, 1143, 837, 721; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.45 (s, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.71 – 7.68 (m, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.5, 162.9, 161.6, 150.5, 150.2, 148.2, 145.6, 132.6, 130.2, 130.1, 125.5 × 2, 121.8, 120.8, 116.9, 116.0 × 2, 115.9, 109.1, 106.2, 102.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H14N4O4Na ([M + Na]+) 409.0907, found 409.0901.

2.1.4.7 (E)-4-((2-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ag)

Yield: 59 %, Red solid, M.p.: 250–251 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1589, 1504, 1328, 1280, 1141, 840, 723; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 9.18 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.82 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.73 – 7.64 (m, 3H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.9, 163.2, 161.9, 152.7, 150.6, 147.4, 145.8, 134.3, 133.1, 130.5, 130.4, 125.7 × 2, 124.6, 120.7, 120.1, 117.2, 116.2 × 2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H13N5O2Na ([M + Na]+) 366.0961, found 366.0955.

2.1.4.8 (E)-4-((4-methoxy-2-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ba)

Yield: 55 %, Green solid, M.p.: 256–257 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1504, 1332, 1278, 1141,831, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.70 – 7.61 (m, 4H), 7.34 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.0, 163.6, 161.2, 160.8, 145.7, 144.2, 132.3, 129.7 × 2, 126.8 × 2, 125.2 × 2, 123.5, 123.4, 119.1, 118.5, 116.1 × 2, 114.4, 56.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H16N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 395.1114, found 395.1107.

2.1.4.9 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5bb)

Yield: 73 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 253–255 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1496, 1328, 1278, 1141, 1091, 833, 734; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 8.13 – 8.09 (m, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.6, 164.3, 163.5, 163.1, 161.2, 160.8, 145.7, 144.2, 129.5, 125.2 × 2, 123.3, 120.2, 119.0, 118.5, 117.1, 116.8, 116.1 × 2, 114.4, 56.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H15FN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 413.1020, found 413.1008.

2.1.4.10 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5bc)

Yield: 46 %, Red solid, M.p.: 233–235 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1600, 1504, 1325, 1280, 1141, 833, 750, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.85 – 7.63 (m, 6H), 7.34 (d, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.3, 163.7, 161.2, 160.8, 145.7, 144.2, 137.1, 129.9 × 2, 128.6 × 2, 125.2 × 2, 123.3, 122.4, 119.1, 118.5, 116.1 × 2, 114.5, 56.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H15ClN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 429.0724, found 429.0718.

2.1.4.11 (E)-4-((4-methoxy-2-(5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5bd)

Yield: 60 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 201–202 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1506, 1328, 1280, 1141, 835, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 7.91 – 7.75 (m, 5H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.0, 163.4, 161.1, 160.6, 145.5, 144.0, 139.0, 132.7, 129.4, 126.9, 125.0 × 2, 123.8, 123.2, 123.0, 118.9, 118.3, 115.9 × 2, 114.1, 56.0, 20.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H18N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 409.1271, found 409.1264.

2.1.4.12 (E)-4-((4-methoxy-2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5be)

Yield: 90 %, Green solid, M.p.: 202–203 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1589, 1506, 1330, 1290, 1141, 839, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 7.81 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.57 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.8, 163.5, 161.5, 160.5, 159.7, 145.4, 144.1, 130.8, 125.0 × 2, 124.5, 123.0, 119.1, 118.9, 118.4, 118.2, 116.1 × 2, 114.2, 111.4, 56.0, 55.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H18N4O4Na ([M + Na]+) 425.1220, found 425.1209.

2.1.4.13 (E)-4-((2-(5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5bf)

Yield: 61 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 271–272 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1589, 1502, 1325, 1288, 1141, 837, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.42 (s, 1H), 7.80 – 7.74 (m, 3H), 7.64 – 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.19 (s, 2H), 3.95 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.6, 162.9, 161.1, 160.6, 150.5, 148.2, 145.5, 143.9, 125.0 × 2, 123.2, 121.9, 118.8, 118.3, 116.9, 115.9 × 2, 114.1, 109.2, 106.3, 102.2, 56.0; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H16N4O5Na ([M + Na]+) 439.1012, found 439.1010.

2.1.4.14 (E)-4-((4-methoxy-2-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5bg)

Yield: 45 %, Red solid, M.p.: 288–289 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1504, 1336, 1280, 1141, 839, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.43 (s, 1H), 9.22 (s, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.82 – 7.75 (m, 3H), 7.68 (s, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 3.96 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.7, 163.1, 161.1, 160.5, 152.6, 147.3, 145.5, 144.0, 134.2, 125.0 × 2, 124.4, 122.8, 119.9, 119.0, 118.4, 115.9 × 2, 114.2, 56.0; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C20H15N5O3Na ([M + Na]+) 396.1067, found 396.1056.

2.1.4.15 (E)-4-((4-ethoxy-2-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ca)

Yield: 76 %, Green solid, M.p.: 242–244 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1477, 1332, 1240, 1141, 833, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.36 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.78 – 7.75 (m, 3H), 7.72 – 7.60 (m, 4H), 7.32 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.8, 163.4, 161.0, 159.9, 145.6, 143.9, 132.2, 129.5 × 2, 126.6 × 2, 125.0 × 2, 123.3, 123.2, 119.2, 118.4, 115.9 × 2, 114.7, 64.1, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H18N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 409.1271, found 409.1263.

2.1.4.16 (E)-4-((4-ethoxy-2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5cb)

Yield: 74 %, Red solid, M.p.: 281–283 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1595 1496, 1328, 1278, 1141, 1093, 833, 734; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 8.13 – 8.10 (m, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.23 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.4, 164.0, 163.3, 162.9, 161.4, 159.8, 145.3, 143.9, 129.3, 125.0 × 2, 123.1, 120.0, 119.1, 118.3, 116.9, 116.6, 116.0 × 2, 114.7, 64.1, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H17FN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 427.1176, found 427.1165.

2.1.4.17 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-ethoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5 cc)

Yield: 81 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 260–262 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1600, 1483, 1327, 1278, 1141, 833, 750, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.31 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.40 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.0, 163.4, 161.0, 159.9, 145.5, 143.8, 136.8, 129.6 × 2, 128.3 × 2, 125.0 × 2, 123.0, 122.2, 119.2, 118.3, 115.9 × 2, 114.7, 64.1, 14.5. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H17ClN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 443.0881, found 443.0873.

2.1.4.18 (E)-4-((4-ethoxy-2-(5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5 cd)

Yield: 63 %, Green solid, M.p.: 220–222 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1506, 1325, 1278, 1143, 833, 684; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 7.87 – 7.82 (m, 2H), 7.79 – 7.76 (m, 3H), 7.64 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.9, 163.3, 161.0, 159.8, 145.5, 143.8, 138.9, 132.7, 129.3, 126.9, 125.0 × 2, 123.7, 123.2, 123.0, 119.1, 118.3, 115.9 × 2, 114.5, 64.0, 20.8, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H20N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 423.1427, found 423.1417.

2.1.4.19 (E)-4-((4-ethoxy-2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ce)

Yield: 82 %, Red solid, M.p.: 230–232 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1467, 1325, 1278, 1141, 833, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 7.78 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H), 7.68 – 7.60 (m, 2H), 7.55 – 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.40 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.7, 163.4, 161.0, 159.9, 159.7, 145.5, 143.9, 130.7, 125.0 × 2, 124.5, 123.1, 119.1, 118.9, 118.3, 118.1, 115.9 × 2, 114.6, 111.3, 64.1, 55.3, 14.5. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H20N4O4Na ([M + Na]+) 439.1376, found 439.1364.

2.1.4.20 (E)-4-((2-(5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-ethoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5cf)

Yield: 71 %, Red solid, M.p.: 251–253 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597 1502, 1323, 1278, 1141, 833, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 7.77 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 3H), 7.64 – 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.30 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 4.21 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.40 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.5, 162.9, 160.9, 159.9, 150.5, 148.1, 145.5, 143.8, 125.0 × 2, 123.2, 121.8, 119.0, 118.2, 116.9, 115.9 × 2, 114.9, 109.1, 106.2, 102.1, 64.0, 14.5. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H18N4O5Na ([M + Na] +) 453.1169, found 453.1163.

2.1.4.21 (E)-4-((4-ethoxy-2-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5cg)

Yield: 74 %, Red solid, M.p.: 269–271 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598 1504, 1338, 1280, 1143, 833, 727; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 9.23 (s, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.78 – 7.75 (m, 3H), 7.68 – 7.61 (m, 2H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 4.23 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMkR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.6, 163.0, 161.0, 159.8, 152.6, 147.3, 145.5, 143.9, 134.2, 125.0 × 2, 124.4, 122.8, 119.9, 119.2, 118.3, 115.9 × 2, 114.7, 64.1, 14.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H17N5O3Na ([M + Na]+) 410.1223, found 410.1213.

2.1.4.22 (E)-4-((2-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-propoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5da)

Yield: 82 %, Red solid, M.p.: 247–248 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1467, 1330, 1236, 1141, 844, 721; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.34 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.81 – 7.75 (m, 3H), 7.69 – 7.59 (m, 4H), 7.32 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.80 (h, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.6, 163.1, 160.8, 159.2, 145.3, 143.6, 131.9, 129.2 × 2, 126.4 × 2, 124.8 × 2, 123.1, 123.0, 118.9, 118.0, 115.7, 115.6, 114.5, 69.6, 21.7, 10.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H20N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 423.1427, found 423.1419.

2.1.4.23 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-propoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5db)

Yield: 74 %, Green solid, M.p.: 235–236 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597 1496, 1328, 1278, 1141, 1093, 839, 734; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 2H), 7.80 – 7.773 (m, 3H), 7.62 (s, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.10 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.81 (p, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.6, 164.2, 163.5, 163.1, 161.1, 160.2, 145.7, 144.0, 129.5, 125.1 × 2, 123.3, 120.2, 119.2, 118.4, 117.0, 116.7, 116.1 × 2, 114.9, 70.0, 22.0, 10.4. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H19FN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 441.1333, found 441.1327.

2.1.4.24 (E)-4-((2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-propoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5dc)

Yield: 64 %, Red solid, M.p.: 209–210 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1600, 1483, 1328, 1284, 1141, 833, 752, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 8.05 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.79 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.10 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.80 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.0, 163.5, 161.0, 160.0, 145.5, 143.9, 136.8, 129.6 × 2, 128.3 × 2, 124.9 × 2, 123.0, 122.2, 119.1, 118.3, 115.9 × 2, 114.7, 69.8, 21.9, 10.2. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H19ClN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 457.1037, found 457.1030.

2.1.4.25 (E)-4-((4-propoxy-2-(5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5dd)

Yield: 59 %, Red solid, M.p.: 214–216 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1506, 1328, 1280, 1141, 842, 727; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.34 (s, 1H), 7.89 – 7.82 (m, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 3H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.43 (m, 2H), 7.32 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 1.80 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.9, 163.3, 160.9, 160.0, 145.5, 143.8, 138.9, 132.6, 129.3, 126.8, 124.9 × 2, 123.7, 123.2, 123.0, 119.1, 118.3, 115.8 × 2, 114.5, 69.8, 21.8, 20.7, 10.2. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H22N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 437.1584, found 437.1575.

2.1.4.26 (E)-4-((2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-propoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5de)

Yield: 73 %, Red solid, M.p.: 198–199 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1595, 1465, 1330, 1273, 1145, 842, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.35 (s, 1H), 7.79 – 7.74 (m, 3H), 7.64 – 7.61 (m, 2H), 7.55 – 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.80 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.1, 163.8, 161.4, 160.4, 160.1, 145.9, 144.3, 131.1, 125.3 × 2, 124.9, 123.4, 119.5, 119.2, 118.7, 118.4, 116.3 × 2, 115.1, 111.7, 70.2, 55.7, 22.3, 10.6. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H22N4O4Na ([M + Na]+) 453.1533, found 453.1524.

2.1.4.27 (E)-4-((2-(5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-4-propoxyphenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5df)

Yield: 77 %, Green solid, M.p.: 251–252 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598 1502, 1384, 1280, 1141, 842, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.37 (s, 1H), 7.78 – 7.74 (m, 3H), 7.63 – 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.32 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.80 (h, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.1, 163.5, 161.6, 160.6, 151.1, 148.8, 146.1, 144.4, 125.5 × 2, 123.8, 122.4, 119.6, 118.9, 117.6, 116.5 × 2, 115.2, 109.7, 106.8, 102.7, 70.4, 22.5, 10.8. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H20N4O5Na ([M + Na]+) 467.1325, found 467.1320.

2.1.4.28 (E)-4-((4-propoxy-2-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5dg)

Yield: 52 %, Red solid, M.p.: 237–238 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597 1504, 1384, 1282, 1139, 840, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.48 (s, 1H), 9.25 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.86 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.80 – 7.71 (m, 4H), 7.66 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.81 (p, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.03 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.5, 162.6, 160.9, 159.8, 151.7, 146.5, 145.3, 143.7, 134.6, 124.7 × 2, 124.4, 122.5, 119.9, 119.0, 118.1, 115.7 × 2, 114.6, 69.6, 21.6, 10.0. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H19N5O3Na ([M + Na]+) 424.1380, found 424.1371.

2.1.4.29 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ea)

Yield: 65 %, Green solid, M.p.: 238–239 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1504, 1330, 1276, 1240, 1141, 835, 727; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.70 – 7.61 (m, 4H), 7.36 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.16 – 6.06 (m, 1H), 5.48 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.3, 163.8, 161.5, 159.9, 146.0, 144.5, 133.5, 132.6, 129.9 × 2, 127.0 × 2, 125.5 × 2, 123.8, 123.6, 119.8, 118.8, 118.5, 116.4 × 2, 115.5, 69.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H18N4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 421.1271, found 421.1263.

2.1.4.30 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5eb)

Yield: 87 %, Green solid, M.p.: 236–237 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1595, 1496, 1328, 1278, 1141, 1093, 837, 734; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.34 (s, 1H), 8.13 – 8.10 (m, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.16 – 6.06 (m, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.9, 164.5, 163.7, 161.5, 159.9, 146.0, 144.5, 133.4, 129.8, 129.7, 125.5 × 2, 123.5, 120.4, 119.8, 118.7, 118.5, 117.3, 117.1, 116.4 × 2, 115.5, 69.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H17FN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 439.1176, found 439.1171.

2.1.4.31 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ec)

Yield: 50 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 241–243 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1589, 1506, 1328, 1282, 1141, 833, 750, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.53 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.18 – 6.04 (m, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.5, 163.9, 161.7, 159.9, 145.9, 144.5, 137.3, 133.4, 130.1 × 2, 128.8 × 2, 125.4 × 2, 123.4, 122.6, 119.9, 118.8, 118.5, 116.4 × 2, 115.5, 69.41; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H17ClN4O3Na ([M + Na]+) 455.0881,found 455.0874.

2.1.4.32 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(m-tolyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ed)

Yield: 86 %, Red solid, M.p.: 213–214 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1506, 1327, 1278, 1141, 842, 727; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.36 (s, 1H), 7.88 – 7.76 (m, 5H), 7.69 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.19 – 6.05 (m, 1H), 5.49 (dd, J = 17.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (dd, J = 10.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.9, 163.3, 161.1, 159.5, 145.6, 144.0, 138.9, 133.0, 132.7, 129.3, 126.9, 125.0 × 2, 123.8, 123.2, 123.0, 119.4, 118.3, 118.0, 115.9 × 2, 114.9, 68.9, 20.8. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H20N4O3N ([M + Na]+) 435.1427, found 435.1420.

2.1.4.33 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ee)

Yield: 54 %, Red solid, M.p.: 186–187 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1598, 1506, 1325, 1278, 1141, 837, 729; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.34 (s, 1H), 7.79 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 3H), 7.70 – 7.62 (m, 2H), 7.57 – 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.19 – 6.05 (m, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 165.3, 164.0, 161.5, 160.3, 160.1, 146.2, 144.7, 133.6, 131.4, 125.6 × 2, 125.1, 123.6, 120.0, 119.5, 119.0, 118.8, 118.7, 116.5 × 2, 115.6, 112.0, 69.5, 55.9. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H20N4O4Na ([M + Na]+) 451.1376, found 451.1369.

2.1.4.34 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5ef)

Yield: 68 %, Brown solid, M.p.: 245–247 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1502, 1458, 1323, 1280, 1141, 835, 731; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H), 7.78 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 3H), 7.67 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 6.14 – 6.06 (m, 1H), 5.48 (dd, J = 17.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (dd, J = 10.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 4.77 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 164.6, 162.8, 161.0, 159.5, 150.5, 148.2, 145.6, 144.0, 133.0, 125.0 × 2, 123.1, 121.9, 119.3, 118.3, 118.0, 116.9, 115.9, 115.8, 114.9, 109.2, 106.3, 102.1, 68.9. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C24H18N4O5Na ([M + Na]+) 465.1169, found 465.1166.

2.1.4.35 (E)-4-((4-(allyloxy)-2-(5-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)phenol (5eg)

Yield: 70 %, Red solid, M.p.: 230–232 ℃; IR cm−1 (KBr): 1597, 1506, 1321, 1278, 1141, 835, 725; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 9.22 (s, 1H), 8.83 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.71 – 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.17 – 6.05 (m, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 19.3 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 163.9, 163.2, 162.3, 159.5, 152.8, 147.5, 145.2, 144.4, 134.4, 133.2, 125.4 × 2, 124.6, 122.8, 120.1, 119.7, 118.6, 118.3, 116.4 × 2, 115.2, 69.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C22H17N5O3Na ([M + Na]+) 422.1223, found 422.1215.

2.2 Biology assays

2.2.1 Cell line and culture conditions

The human lung cancer cells (A549), human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), human colon cancer cells (HCT116), human hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HePG2), human breast cancer cells (MCF-7), HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells (HT1080), human lung epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were obtained from Cell Bank/Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We used RPMI-1640 and DMEM medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 1 % penicillin for cell growth under the condition of 37 °C in 5 % CO2. 5- Fluorouracil (5-FU) was employed as positive control drug.

2.2.2 Cytotoxic assays

The MTT assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of novel synthesized derivatives (5aa ∼ eg) on cell viability. When cells were in exponentially growing phase, seeded at a concentration of 10,000 cells/well on 96 tissue culture plate overnight. After the culture medium replaced with a fresh one, a solution of synthesized compounds in DMSO was added to reach the concentration of 200 μmol/L. After 72 h, the drug solutions discarded and cells were washed with PBS. Then 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/mL, in PBS) was added into each well and cultured for another 4 h. Subsequently, the supernatant replaced with DMSO to soften the formed formazan. In parallel, we used negative control, blank and positive control (5-fluorouracil, 5-FU) in the same conditions. At the final step, absorbance at the wavelength of 490 nm was read by a microplate reader. the IC50 values for some compounds were also calculated. All the experiments were repeated three times.

2.2.3 Cell cycle arrest assay

HCT116 cells (1 × 106/well) were spread in 6-well plates overnight; the cells were treated with different concentration of compound 5df for 48 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and digested with trypsin. The supernatant was removed via centrifugation and fixed overnight in 70 % ethanol. The cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in a 190 µL staining buffer containing 4 µL of 1 mg/mL PI (propidium iodide), 4 µL of 10 mg/mL RNaseA (ribonuclease), and 0.2 µL Tritonx-100. After staining for 20 min in the dark, the cell cycle distribution was detected using flow cytometry (American BD,Canto II plus).

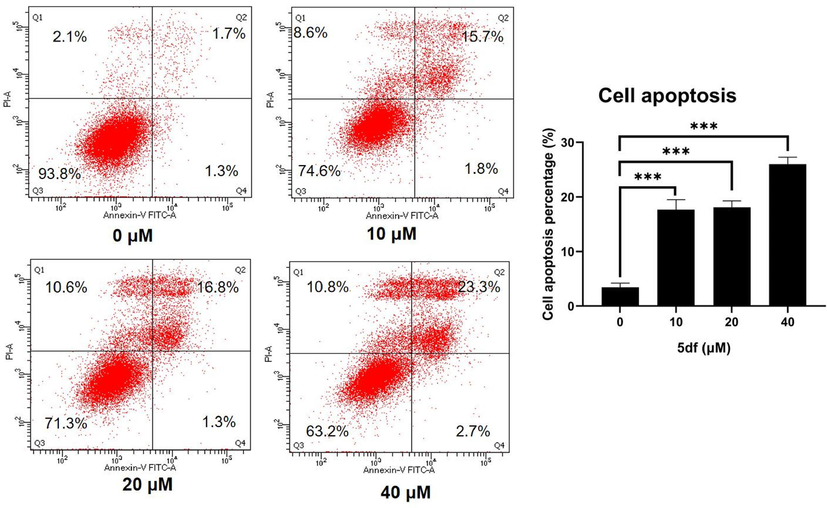

2.2.4 Cell apoptosis assay

HCT116 cells (2.2 × 106/well) were grown in 6-well plates and treated with different concentrations of compound 5df for 48 h. After incubation, the cells were trypsinised and washed with PBS. The obtained cell pellet was resuspended in 1x Annexin binding buffer. 5 μL of annexin V/FITC and 10 μL of PI were added to the resuspended cells and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Thereafter, the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

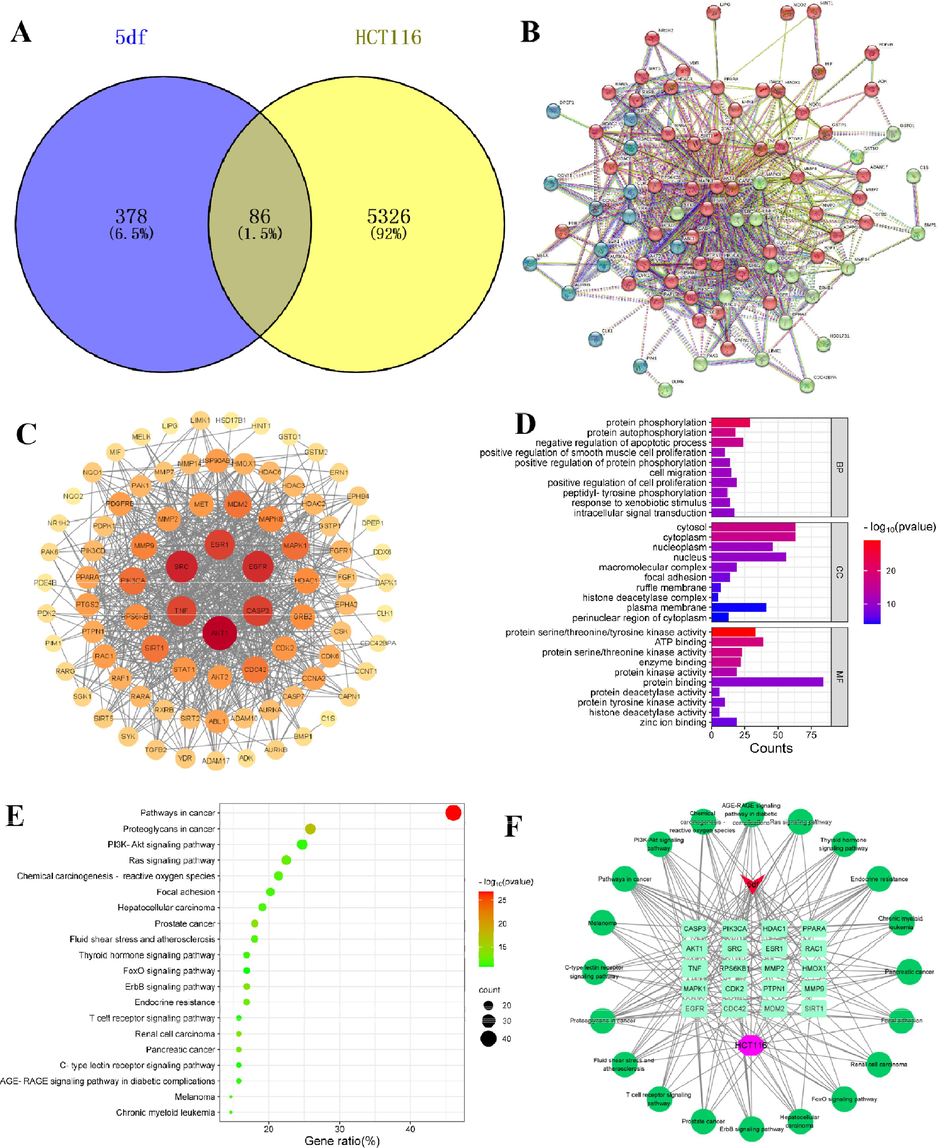

2.3 Analysis of network pharmacology

2.3.1 Prediction of disease targets of compound 5df

Compound 5df was draw in ChemBioDraw and saved as “sdf” file format. This file was then imported into PharmMapper database (https://lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/submitfile.html) (Wang et al., 2016), Swiss target prediction database (https://www.swisstargetprediction.ch) (Gfeller et al., 2013), inputting the protein names with the species limited to “Homo sapiens”, and we could receive their official symbol. After these operations, proteins information of compound targets and known targets was obtained.

2.3.2 Gene screening of HCT116 related targets

Using “HCT116” as the search keywords, we searched Gene Cards database (https://www.genecards.org/) (Stelzer et al., 2016) to excavate potential targets associated with HCT116. Venny 2.1.0 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) software was used to identify the targets of compound 5df against HCT116 (Sun et al., 2019).

2.3.3 Construction of protein–protein interaction (PPI) network

To further identify the core regulatory targets, PPI analysis was performed by submitting overlapping targets of active compounds in HCT116 to the STRING 11.5 database (https://string-db.org) (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). The species type was set to “Homo sapiens”, the minimum interaction threshold was set to “highest confidence” >0.4, and the rest was set as the default. Finally, the PPI result was imported into Cytoscape 3.8.0 software to construct a PPI network. Finally, the core targets of the top 20 were also exhibited.

2.3.4 Go and KEGG enrichment analysis

To further understand the functions of core target genes and the main action pathways of the active substances of 5df, the disease-related targets obtained from the above screening were entered into the DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (Sherman et al., 2022). The list of genes of 5df targets against HCT116 was uploaded to the DAVID searching tool. Here, the species section was selected as “homo sapiens”, and all target gene names were corrected to their official names (official gene symbol), and the threshold of p < 0.05 was set for GO and KEGG enrichment before running the tool.

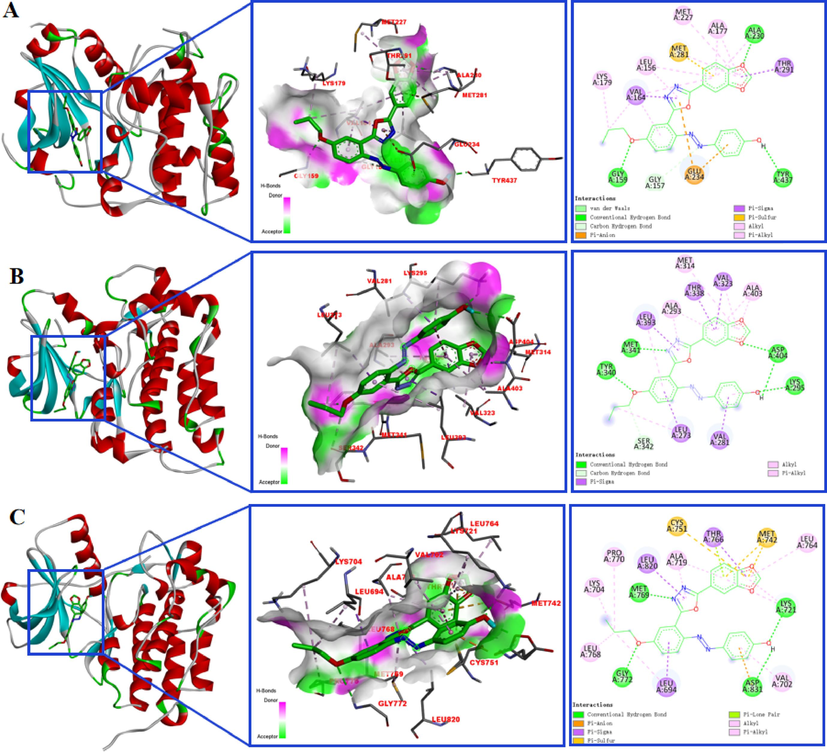

2.4 Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed among the top three potential target proteins of HCT116 with 5df. The 2D structure of compound 5df was drawn by ChemDraw2019, and saved as cdx file. Then, MM2 force field was used to optimize the 3D structure of the ligand. The 3D structures of the target proteins were downloaded from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org) (AKT1, PDB: 3MV5; SRC, PDB: 1Y57; EGFR, PDB: 1 M17. The water molecules and the original ligands were removed from the target protein through Discovery studio. Later, the target proteins were imported into AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 for hydrogenation, charge calculation, and non-polar hydrogen combination, and then the result was stored in PDBQT format. The 3D coordinates of active sites (x, y, z) were as follows: AKT1 (1.931, −0.696, 25.291), SRC (9.48, 38.365, 38.325), EGFR (30.465, 9.823, 59.384). Finally, run AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 for molecular docking, and use Discovery studio 2021 to visualize the results (Trott & Olson, 2010).

2.5 Data analyses

The cell growth inhibition rate of compounds against six human cancer cell lines were calculated by the following formula: Inhibition rate (%) = (ODnegative control – ODexperiment)/(ODnegative control – ODblank) × 100 %. The relative cell viability was calculated with the formula: Cell viability rate (%) = (ODexperiment – ODblank)/(ODnegative control – ODblank) × 100 %. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, and each group was performed three times. Statistical analysis was processed by the SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemistry

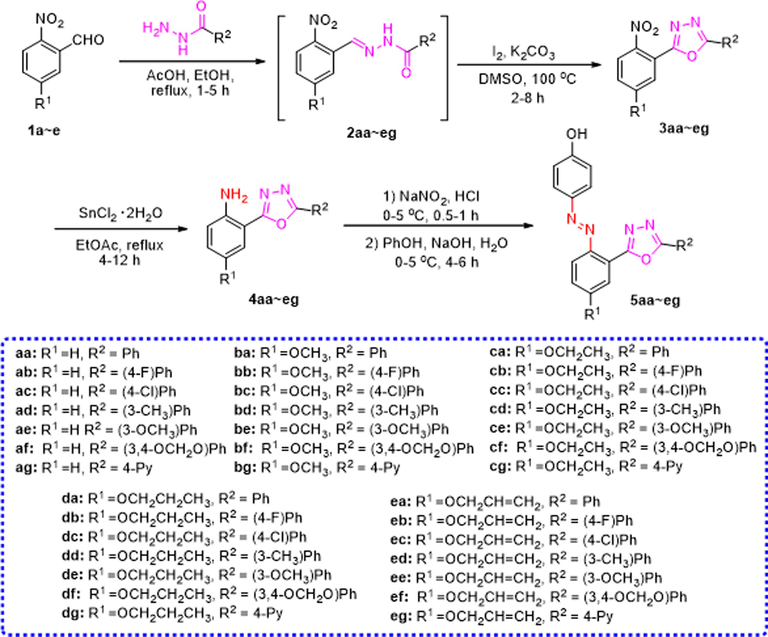

As illustrated in Scheme 1, the synthesis of the azophenol derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety was performed starting from the available chemicals. Firstly, according to the method we reported, a nucleophilic addition and elimination reaction between o-nitrobenzaldehyde and substituted hydrazides yielded acylhydrazone intermediates (2aa ∼ eg) in the presence of acetic acid. Subsequently, these intermediates underwent a ring-closing reaction facilitated by iodine to form 1,3,4-oxadiazoles (3aa ∼ eg) (Yu et al., 2021). In the subsequent step, the corresponding oxadiazoles were reacted with hydrated tin(II) chloride to yield intermediates 4aa ∼ eg, with yields ranging from 48 % to 93 %. Finally, compounds 4aa ∼ eg reacted with sodium nitrite to produce diazonium salts, which were further reacted with phenol to give azophenol derivatives containing the 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety (5aa ∼ eg) in moderate to good yields (Table 1).

General synthetic procedure of azophenol derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety (5aa ∼ eg).

Compound

R1

R2

Yield (%)

M.p. (oC)

5aa

H

Ph

48

281–283

5ab

H

(4-F)Ph

89

273–275

5ac

H

(4-Cl)Ph

73

238–239

5ad

H

(3-CH3)Ph

38

214–216

5ae

H

(3-OCH3)Ph

89

253–255

5af

H

(3,4-OCH2O)Ph

69

289–291

5ag

H

4-Py

59

250–251

5ba

OCH3

Ph

55

256–257

5bb

OCH3

(4-F)Ph

73

253–255

5bc

OCH3

(4-Cl)Ph

46

233–235

5bd

OCH3

(3-CH3)Ph

60

201–202

5be

OCH3

(3-OCH3)Ph

90

202–203

5bf

OCH3

(3,4-OCH2O)Ph

61

271–272

5bg

OCH3

4-Py

45

288–289

5ca

OCH2CH3

Ph

76

242–244

5cb

OCH2CH3

(4-F)Ph

74

281–283

5cc

OCH2CH3

(4-Cl)Ph

81

260–262

5cd

OCH2CH3

(3-CH3)Ph

63

220–222

5ce

OCH2CH3

(3-OCH3)Ph

82

230–232

5cf

OCH2CH3

(3,4-OCH2O)Ph

71

251–253

5cg

OCH2CH3

4-Py

74

269–271

5da

OCH2CH2CH3

Ph

82

247–248

5db

OCH2CH2CH3

(4-F)Ph

74

235–236

5dc

OCH2CH2CH3

(4-Cl)Ph

64

209–210

5dd

OCH2CH2CH3

(3-CH3)Ph

59

214–216

5de

OCH2CH2CH3

(3-OCH3)Ph

73

198–199

5df

OCH2CH2CH3

(3,4-OCH2O)Ph

77

251–252

5dg

OCH2CH2CH3

4-Py

52

237–238

5ea

OCH2CH = CH2

Ph

65

238–239

5eb

OCH2CH = CH2

(4-F)Ph

87

236–237

5ec

OCH2CH = CH2

(4-Cl)Ph

50

241–243

5ed

OCH2CH = CH2

(3-CH3)Ph

86

213–214

5ee

OCH2CH = CH2

(3-OCH3)Ph

54

186–187

5ef

OCH2CH = CH2

(3,4-OCH2O)Ph

68

245–247

5eg

OCH2CH = CH2

4-Py

70

230–232

The structural characterization of all synthesized compounds was carried out using 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HRMS (see Supplementary Materials). For example, the 1H NMR spectrum of 5af showed a single peak at 10.45 ppm which could be assigned to –OH. two double peaks at 7.83 ppm (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H) and 6.95 ppm (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H) were attributed to the protons of phenol. The other a single peak at 7.45 ppm and two double peaks at 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H) and 7.13 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H) ppm belonged to the protons of benzo[d][1,3]dioxole. The single peaks of OCH2O protons of benzo[d][1,3]dioxole moiety appeared at 6.18 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectrum of 5af, the signals at 164.5 and 162.9 ppm were assigned to the carbons in 1,3,4-oxadiazole. The carbon linked to hydroxyl groups appeared at 161.6 ppm. The signals at 125.5 and 116.0 ppm were assigned to the carbons of phenol. The single peaks at 102.1 ppm belonged to OCH2O. The remaining multiple single peaks observed at 150.5–106.2 ppm were attributed to aromatic rings. The HRMS spectrum of 5af showed a molecular ion peak at m/z 409.0907 as [M + Na]+.

3.2 Biology assays

3.2.1 In vitro anticancer activity

The synthesized azophenol derivatives (5aa ∼ eg) were assessed for their in vitro anticancer activities at 200 µmol/L against six human cancer cell lines, which included lung cancer cells (A549), cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), colon cancer cells (HCT116), hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HePG2), breast cancer cells (MCF-7), and fibrosarcoma cells (HT1080). The MTT assay was used for this evaluation, and 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) served as the positive control. As indicated in Table 2, most of the target compounds displayed significant anticancer activity, particularly against HCT116 and HePG2. For instance, compounds 5be, 5cb, 5db, 5dc, 5df, 5ec and 5eg exhibited potent cytotoxicity against HCT116 and HePG2, with growth inhibition rates exceeding 60 %. Besides, 5db, 5dc, 5df and 5ec also demonstrated noteworthy cytotoxicity against HeLa, with growth inhibition rates of 85.81 %, 88.68 %, 78.87 %, and 80.13 %, respectively. Of particular note, compound 5df exhibited substantial antineoplastic activity across all six tumor cell lines, with growth inhibition rates surpassing 50 %. These results underscored the potent anticancer effects of azophenol derivatives containing the 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety. Furthermore, preliminary structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies were also conducted. For example, to HCT116 and HePG2 cells, introduction of ethoxy or propoxy groups on R2 led to more potent compounds (5ca, 5da vs 5aa). When R1 was a ethoxy group, the compound 5be with R2 = (4-F)Ph exhibited superior anticancer activity compared to other 4-substituted phenyl variations. Similarly, when R1 was a propoxy group, compounds 5cb and 5df, with the introduction of (4-F)Ph or benzo[d][1,3]dioxole groups on R2 displayed more potent antitumor activity. On the contrary, introducing pyridine heterocycles in R2 did not improve the activity of the compounds, such as 5ag, 5bg, 5cg. This outcome indicated that the rational incorporation of propoxy group on R1 and benzo[d][1,3]dioxole group on R2 can distinct influence the anticancer effect.

Compound

Growth Inhibition Rate (%)a

A549

HeLa

HCT116

HePG2

MCF-7

HT1080

5aa

NAb

NA

NA

42.95 ± 2.14

NA

NA

5ab

NA

48.68 ± 5.23

13.58 ± 4.46

70.65 ± 1.38

33.92 ± 6.35

NA

5ac

NA

NA

52.93 ± 7.12

40.93 ± 3.09

NA

NA

5ad

14.74 ± 4.77

31.15 ± 4.6

33 ± 5.13

79.03 ± 3.57

NA

NA

5ae

NA

43.51 ± 8.65

51.48 ± 2.66

67.95 ± 3.58

NA

NA

5af

NA

NA

28.99 ± 2.96

54.34 ± 3.1

NA

NA

5ag

16.51 ± 6.66

3.66 ± 30.35

14.78 ± 3.12

55.55 ± 3.99

NA

NA

5ba

NA

NA

35.7 ± 3.03

41.06 ± 2.88

NA

24.62 ± 1.62

5bb

NA

NA

17.31 ± 4.67

17.5 ± 6.29

13.51 ± 4.94

38.74 ± 3.47

5bc

19.15 ± 4.28

32.4 ± 5.1

75.9 ± 3.42

35.54 ± 5.84

NA

NA

5bd

–

NA

NA

40 ± 4.3

NA

44.17 ± 7.21

5be

13.41 ± 2.33

39.82 ± 4.11

79.71 ± 0.37

73.11 ± 3.36

NA

NA

5bf

NA

18.38 ± 2.55

NA

59.67 ± 5.65

NA

34.15 ± 0.14

5bg

NA

NA

NA

55.72 ± 5.02

47.86 ± 2.99

18.74 ± 2.87

5ca

51.96 ± 2.67

NA

35.5 ± 5.92

60.69 ± 3.29

NA

NA

5cb

NA

NA

65.22 ± 1.04

69.22 ± 4.16

NA

NA

5cc

45.69 ± 0.37

83.7 ± 2.34

62.66 ± 3.94

42 ± 5.84

58.52 ± 4.6

18.69 ± 3.16

5cd

NA

NA

22.29 ± 3.14

39.95 ± 5.51

9.04 ± 4.29

NA

5ce

NA

NA

23.38 ± 6.7

84.57 ± 3.19

28.25 ± 3.77

NA

5cf

NA

NA

7.24 ± 4.65

42.05 ± 4.48

NA

23.93 ± 6.05

5cg

12.42 ± 2.64

67.37 ± 5.11

12.58 ± 1.59

23.11 ± 2.47

10.13 ± 2.64

6.81 ± 1.76

5da

33.56 ± 5.71

27.72 ± 5.08

48 ± 2.28

83.85 ± 5.15

18.49 ± 5.43

NA

5db

NA

85.81 ± 1.26

85.41 ± 2.35

78.24 ± 2.01

49.24 ± 2.78

6.81 ± 1.76

5dc

NA

88.68 ± 1.39

62.39 ± 5.71

88.24 ± 2.01

NA

NA

5dd

NA

14.05 ± 4.84

46.51 ± 2.11

87.08 ± 2.39

44.5 ± 3

NA

5de

NA

59.43 ± 6.2

53.91 ± 2.04

53.55 ± 5.42

NA

45.35 ± 5.2

5df

62.09 ± 4.68

78.87 ± 3.78

92.47 ± 3.5

73.66 ± 5.79

64.22 ± 0.94

54.23 ± 1.94

5dg

NA

27.97 ± 8.79

26.95 ± 3.78

78.72 ± 3.32

NA

18.14 ± 2.83

5ea

NA

6.07 ± 15.84

7.63 ± 5.3

44.62 ± 5.6

NA

7.91 ± 1.11

5eb

NA

NA

36.93 ± 2.22

43.53 ± 4.97

26.18 ± 4.18

38.09 ± 5.78

5ec

40.9 ± 4.76

80.13 ± 1.58

65.03 ± 3.51

81.13 ± 7.22

28.74 ± 3.64

24.6 ± 7.42

5ed

NA

20.96 ± 5.82

36.75 ± 4.74

55.64 ± 5.34

21.08 ± 8.97

35.06 ± 6.57

5ee

NA

NA

30.62 ± 2.63

62.64 ± 4.96

10.03 ± 7.33

NA

5ef

NA

NA

41.56 ± 0.64

56.18 ± 5.23

31.93 ± 5.4

NA

5eg

53.9 ± 1.02

50.16 ± 2.47

70.52 ± 1.31

87.69 ± 0.11

38.81 ± 4.15

21.06 ± 2.16

5-FU

81.16 ± 2.95

83.74 ± 2.93

92.36 ± 3.64

88.02 ± 3.21

88.84 ± 1.26

69.01 ± 3.90

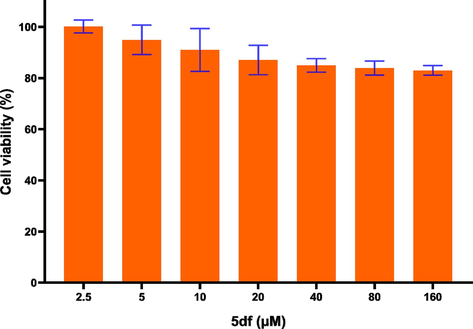

Additionally, the IC50 values (50 % inhibitory concentrations) of the tested compounds, where growth inhibition rates were over 70 %, were evaluated and consolidated in Table 3. Among these derivatives, the IC50 values of 5db and 5df against HCT116 were measured at 9.96 and 4.09 μM, respectively. For HePG2 cells, the IC50 value of 5dc was determined to be 9.39 μM. These values are in close proximity to or even surpass the IC50 of 5-FU, the utilized positive control. In order to evaluate the safety of these new synthetic compounds, we selected the most active compound 5df and tested tis toxicity to human normal lung epithelial cells (BEAS-2B). The result showed that 5df displayed low cytotoxicity against BEAS-2B with the cell viabilities over 80 % even at concentration of 160 μM, which indicated that compound 5df showed higher selectivity to tumor cells than normal cells (Fig. 2).

Compound

IC50 (μM)a

HeLa

HCT116

HePG2

5ab

NDb

ND

>100

5ad

ND

ND

>100

5bc

ND

>100

ND

5be

ND

40.56 ± 0.45

29.6 ± 0.73

5cc

>100

ND

ND

5ce

ND

ND

>100

5da

ND

ND

13.7 ± 0.72

5db

70.77 ± 0.73

9.96 ± 0.08

44.64 ± 0.59

5dc

24.97 ± 0.16

ND

9.39 ± 0.45

5dd

ND

ND

38.43 ± 0.69

5dg

ND

ND

>100

5df

>100

4.09 ± 0.04

>100

5ec

21.79 ± 0.35

ND

36.77 ± 0.51

5eg

ND

61.69 ± 0.77

>100

5-FU

51.65 ± 0.78

2.20 ± 0.13

32.56 ± 0.64

Relative cell viabilities of BEAS-2B treated with compound 5df.

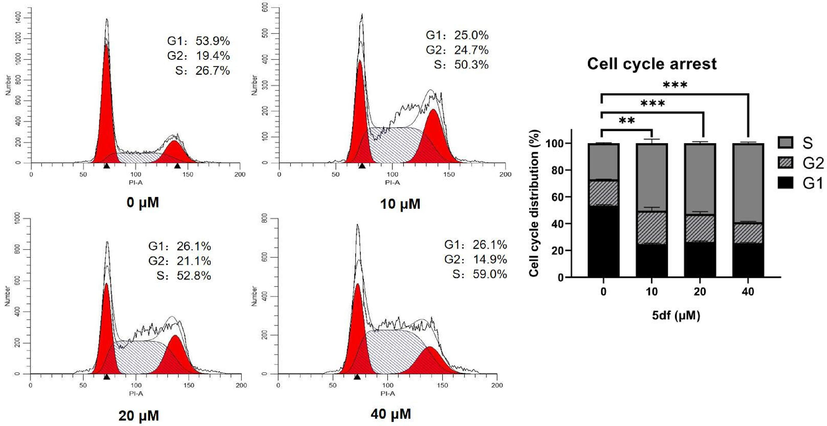

3.2.2 Cell cycle analysis

Motivated by the initial in vitro antiproliferative screening outcomes, the underlying anticancer mechanism of this series compounds was further explored. Among the compounds, the most potent candidate, 5df, was chosen to delve into its impact on the cell cycle progression of HCT116 cancer cells, employing flow cytometry analysis. For this investigation, HCT116 cancer cells were subjected to treatment with either DMSO (control group) or varying concentrations of 5df (10, 20, 40 μM) for a duration of 48 h. As depicted in Fig. 3, the percentage of cells in the S phase in presence of 5df exhibited values of 50.3 %, 52.8 %, and 59.0 %, respectively, while 26.7 % of the S phase was detected for the control group. These finding demonstrated that compound 5df elicited a noticeable concentration-dependent S-phase arrest.

Effect of compound 5df on cell cycle in HCT116 cells. Flow cytometry of HCT116 cells treated with 5df for 48 h (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

3.2.3 Cell apoptosis analysis

Moreover, cell apoptosis analysis was conducted on HCT116 cells exposed to escalating concentrations of 5df (0, 10, 20, 40 μM), utilizing the annexin V-FITC-PI assay. As illustrated in Fig. 4, following a 48-hour incubation period with 5df, the collective percentages of late (Q2) and early (Q3) apoptotic cells exhibited increases to 17.5 %, 18.1 %, and 26.0 %, respectively. In contrast, the control group displayed a mere 3.0 % of apoptotic cells. Consequently, these results demonstrated that compound 5df had antiproliferative activity through dose-dependently inducing cellular apoptosis.

Effect of compound 5df on cell apoptosis in HCT116 cells. Flow cytometric analysis of apoptotic cells after treatment of HCT116 cells with 5df for 48 h (*** p < 0.001).

3.3 Analysis of network pharmacology

Network pharmacology, an emerging discipline centered around the interplay of disease-gene-drug targets, has evolved into an efficacious research methodology for exploring active compounds and comprehending the mechanisms underlying the pharmacodynamic actions of these compounds (Hopkins, 2008; Zhu et al., 2022). In the context of this study, the network pharmacology approach was employed to uncover the mechanism of action and potential targets associated with compound 5df in its application for HCT116 treatment.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, by searching the public databases (Swiss target prediction, PharmMapper, Gene Cards), confining the result to “Homo sapiens”, 378 targets related with compound 5df and 5412 targets with HCT116 were collected, respectively. The utilization of Venny 2.1.0 facilitated the calculation of the intersection between 5df targets and HCT116 targets, resulting in 86 intersection targets (Fig. 5, A). Subsequently, high-confidence protein interaction data were extracted by employing target proteins and their corresponding components from the STRING database. This process eliminated uninvolved proteins, thereby yielding 86 shared proteins between 5df and HCT116 (Fig. 5, B). The obtained protein–protein interaction (PPI) outcomes were imported into Cytoscape 3.8.0 software, enabling the construction of a PPI network (Fig. 5, C). The visualization also highlighted the twenty core targets. Notably, the top three targets, AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (AKT1), SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase (SRC), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), emerged as the most plausible targets of action for compound 5df (Table 4). AKT1 belongs to a family of kinases AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, can include the coexpression of multiple family members in normal tissues and tumors. AKT is part of the PI3K/AKT pathway that encompasses multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (PI3K and mTOR) and integrates extracellular signals with cell growth, proliferation, and survival. It is often activated in malignant cells, and is a promising point of therapeutic intervention for many cancers (Nicholson and Anderson, 2002; Cheng et al. 2005). SRC kinase is a group of proteins with tyrosine protein kinase activity that are overexpressed and highly activated in various human tumor cells, it can activate the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways related to tumor growth (Boggon and Eck, 2004; Peiró et al., 2014). EGFR is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family, widely distributed on the surface of mammalian epithelial cells, fibroblasts, glial cells, keratinocytes, and other cells. The EGFR signaling pathway plays an important role in physiological processes such as cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. When EGFR undergoes mutations, it leads to sustained activation of the EGFR signaling pathway, leading to abnormal cell proliferation (Sabbah et al., 2020). The above three proteins were closely related to the development of tumor cells and might be the main targets of compound 5df.

Analysis of network pharmacology of 5df-HCT116. (A) The Venn diagram of compound 5df and HCT116 targets; (B) Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network; (C) Topological network schematic of proteins targeted by 5df and associated with HCT116; (D) Analysis of potential targets of 5df for anti-HCT116 based on GO enrichment; (E) Analysis of potential targets of 5df for anti-HCT116 based on KEGG enrichment; (F) Constituent-target-pathway network of top 20 pathways.

Target ID

Gene name

Degree

Betweenness

Closeness

AKT1

AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1

57

807.0940761

0.008695652

SRC

SRC Proto-Oncogene, Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase

50

470.9976093

0.008130081

EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

48

569.0928943

0.008064516

CASP3

Caspase 3

44

378.868961

0.007692308

ESR1

Estrogen Receptor 1

44

497.4969143

0.007633588

TNF

Tumor Necrosis Factor

43

470.5896637

0.007692308

MAPK1

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 1

35

168.7924717

0.007092199

PIK3CA

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha

35

150.0517497

0.006944444

SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

34

221.1860693

0.007142857

MDM2

MDM2 Proto-Oncogene

34

265.0791359

0.006993007

CDC42

Cell Division Cycle 42

33

250.7977111

0.006849315

MMP9

Matrix Metallopeptidase 9

31

233.3490098

0.006944444

HDAC1

Histone Deacetylase 1

29

265.6142845

0.006578947

RPS6KB1

Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase B1

28

100.9209659

0.006756757

CDK2

Cyclin Dependent Kinase 2

26

130.9764011

0.006578947

MMP2

Matrix Metallopeptidase 2

25

127.7503376

0.006578947

RAC1

Rac Family Small GTPase 1

24

107.5536357

0.00617284

PPARA

Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Alpha

22

366.0219331

0.006329114

PTPN1

Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non-Receptor Type 1

20

200.0227838

0.00617284

HMOX1

Heme Oxygenase 1

18

224.9469155

0.006134969

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were also executed to shed light on the functions and enriched pathways attributed to the potential HCT116 genes targeted by compound 5df. The analysis of biological processes (BP) outcomes indicated that compound 5df's targets involved in anti-HCT116 were prominently enriched in processes such as protein phosphorylation, protein autophosphorylation, negative regulation of the apoptotic process, and other biological processes. Cellular components (CC) analysis underscored the significance of cellular elements like cytosol, cytoplasm, nucleoplasm, and other cellular components. The molecular functions (MF) analysis results underscored that protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity, ATP binding, protein serine/threonine kinase activity and other molecular functions played an important role (Fig. 5, D). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis yielded a notable result, 136 signaling pathways relevant to the interaction between 5df and HCT116, were statistically significant. These included pathways associated with pathways in cancer, proteoglycans in cancer, prostate cancer, ErbB signaling pathway, and more. A visual representation in the form of a bubble diagram depicted the top 20 pathways which were significant enrichment potential, along with the highest count of associated genes (Fig. 5, E). Furthermore, a network was constructed to depict the relationships between ingredients, targets, and the top 20 pathways (Fig. 5, F). Among the pathways with the highest counts, such as pathways in cancer, proteoglycans in cancer, and prostate cancer, may contribute to the anti-HCT116 effect exhibited by 5df.

3.4 Molecular docking

Molecular docking is a cutting-edge scientific method that can match small molecules to the binding sites of proteins and evaluate their binding strength to predict the binding mode and binding free energy of a given protein and small molecule ligand, and then study their function and mechanism of action (Kitchen et al., 2004; Saikia and Bordoloi, 2019). In recent years, molecular docking has played an important role in the validation of drug targets, and provided effective tools for the development of novel anticancer drugs (Premkumar et al., 2016; Shaheen et al., 2020; Eze et al., 2022). In this work, molecular docking studies were conducted between the compound 5df and the three key targets, AKT1 (PDB: 3MV5), SRC (PDB: 1Y57), and EGFR (PDB: 1 M17) which were high-degree nodes in the interaction network to verify the results of network pharmacology analysis. The docking results showed that compound 5df could be bound into the docking pockets with binding energies lower than −8 kcal/mol, and had good docking activities between the target proteins, suggesting they played a critical role in the response to compound 5df in HCT116. For example, compound 5df bound to AKT1 by forming hydrogen bonds with GLY159, ALA230, TYR437 (Fig. 6, A), which had the same binding sites and similar binding patterns as the AKT1 inhibitors that Freeman-Cook reported (Freeman-Cook et al., 2010). As shown in Fig. 6, B, Cowan-Jacob et al. demonstrated that the binding site of RSC inhibitors is composed of amino acid residues GLY274, LEU273, MET341, ALA293, LEU393, VAL281, GLN275 etc, by cultivating protein and drug complexes (Cowan-Jacob et al., 2005). There were also four hydrogen bonds, LYS295, TYR340, MET341 and ASP404 formed between 5df and SRC, indicates that the compound could bind to the active site of RSC. Similarly, compound 5df was predicted to dock into the binding pocket of EGFR via hydrogen bonds LYS721, MET769, GLY772 and ASP831 (Fig. 6, C), which was the active site of EGFR (Stamos et al., 2002). The above data suggested that compound 5df could potentially influence their function by inhibiting the binding of the docking pockets to the target receptors and played an crucial role in anti-HCT116.

Molecular models of 5df binding to AKT1 (A), SRC (B), and EGFR (C).

4 Conclusion

In summary, this study encompassed the synthesis of thirty-five azophenol derivatives containing the 1,3,4-oxadiazoles moiety, whose structures were elucidated through 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HRMS analyses. The anticancer activity of all synthesized compounds was evaluated in vitro against six different human cancer cell lines via the MTT assay. Remarkably, compound 5df exhibited a notable inhibition of HCT116 cell proliferation with an IC50 value of 4.09 ± 0.04 µM, and low toxicity against normal human cells. Further mechanism studies showed that 5df significantly arrested cell cycle at S phase, induced apoptosis via flow cytometric analysis. In addition, network pharmacology computations pointed towards AKT1, SRC, and EGFR as plausible target proteins for 5df against HCT116 cells. Molecular docking studies further confirmed the good binding interactions of 5df with these three target proteins. Collectively, these results demonstrated that compound 5df could be a potent anticancer candidate reagent with low toxicity, and worthy for further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82260833), Guizhou Provincial Natural Science Foundation [QKHJ-ZK(2022)YB503], Science and Technology Planning Project of Guizhou Province [QKHF-ZK(2023)G426].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- New 1,3,4-oxadiazole/oxime hybrids: design, synthesis, anti-inflammatory, COX inhibitory activities and ulcerogenic liability. Bioorg. Chem.. 2017;74:15-29.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 2,4'-bis substituted diphenylamines as anticancer agents and potential epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2010;45(9):4113-4121.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular properties prediction and synthesis of novel 1,3,4-oxadiazole analogues as potent antimicrobial and antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2011;21(24):7246-7250.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antitubercular activity of imidazo [2,1-b]thiazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2001;36:743-746.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities and absorption properties of disazo dyes containing imidazole and pyrazole moieties. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A Pure Appl. Chem.. 2017;54(4):236-242.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles: an emerging scaffold to target growth factors, enzymes and kinases as anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2015;97:124-141.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Classifications, properties, recent synthesis and applications of azo dyes. Heliyon. 2020;6(1):e03271.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure and regulation of Src family kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23(48):7918-7927.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 2018;68(6):394-424.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Akt/PKB pathway: molecular target for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2005;24(50):7482-7492.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The crystal structure of a c-Src complex in an active conformation suggests possible steps in c-Src activation. Structure. 2005;13(6):861-871.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Azole-pyrimidine hybrid anticancer agents: a review of molecular structure, structure activity relationship, and molecular docking. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.. 2022;22(16):2822-2851.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design of selective, ATP-competitive inhibitors of Akt. J. Med. Chem.. 2010;53(12):4615-4622.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shaping the interaction landscape of bioactive molecules. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(23):3073-3079.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design and synthesis of new norfloxacin-1,3,4-oxadiazole hybrids as antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2019;136:104966

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase. 3. Structure-activity relationship of tricyclics bearing imidazoline, oxadiazole, or tetrazole groups. J. Med. Chem.. 1996;39(9):1857-1863.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol.. 2008;4(11):682-690.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.. 2004;3(11):935-949.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel substituted aniline based heterocyclic dispersed azo dyes coupling with 5-methyl-2-(6-methyl-1, 3-benzothiazol-2-yl)-2, 4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one: synthesis, structural, computational and biological studies. J. Mol. Struct.. 2020;1205:127576

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel isoxazolone based azo dyes: synthesis, characterization, computational, solvatochromic UV-Vis absorption and biological studies. J. Mol. Struct.. 2021;1244:130933

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coumarin-benzothiazole based azo dyes: synthesis, characterization, computational, photophysical and biological studies. J. Mol. Struct.. 2021;1246:131170

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A new sulphur containing heterocycles having azo linkage: synthesis, structural characterization and biological evaluation. J. King Saud Univ. Sci.. 2020;32(8):3313-3320.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel push-pull heterocyclic azo disperse dyes containing piperazine moiety: Synthesis, spectral properties, antioxidant activity and dyeing performance on polyester fibers. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2015;150:799-805.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The protein kinase B/Akt signalling pathway in human malignancy. Cell. Signal.. 2002;14(5):381-395.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Src, a potential target for overcoming trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;111(4):689-695.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Risk scores for predicting advanced colorectal neoplasia in the average-risk population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol.. 2018;113(12):1788-1800.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vibrational spectroscopic, molecular docking and density functional theory studies on 2-acetylamino-5-bromo-6-methylpyridine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2016;82:115-125.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, cyclic voltammetric and cytotoxic studies of azo dyes containing thiazole moiety. Chem. Data Collect.. 2020;25:100334

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) structure, signaling pathways, interactions, and recent updates of EGFR inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem.. 2020;20(10):815-834.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular docking: challenges, advances and its use in drug discovery perspective. Curr. Drug Targets. 2019;20(5):501-521.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review of colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, development, symptoms and diagnosis. Cancers (basel).. 2021;13(9):2025.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of new series of hexahydroquinoline and fused quinoline derivatives as potent inhibitors of wild-type EGFR and mutant EGFR (L858R and T790M) Bioorg. Chem.. 2020;105:104274

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ube2v1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of Sirt1 promotes metastasis of colorectal cancer by epigenetically suppressing autophagy. J. Hematol. Oncol.. 2018;11(1):95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update) Nucleic Acids Res.. 2022;50(W1):W216-W221.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Derivatives of benzimidazole pharmacophore: synthesis, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic and DNA cleavage studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2010;45(5):1753-1759.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain alone and in complex with a 4-anilinoquinazoline inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem.. 2002;277(48):46265-46272.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The genecards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2016;54

- [Google Scholar]

- DiVenn: an interactive and integrated web-based visualization tool for comparing gene lists. Front. Genet.. 2019;10:421.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 2011;71(3):209-249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2019;47(D1):D607-D613.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pyridine scaffolds, phenols and derivatives of azo moiety: current therapeutic perspectives. Molecules. 2021;26(16):4872.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.. 2010;31(2):455-461.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhancing the enrichment of pharmacophore-based target prediction for the polypharmacological profiles of drugs. J. Chem. Inf. Model.. 2016;56(6):1175-1183.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Expedient discovery for novel antifungal leads: 1,3,4-Oxadiazole derivatives bearing a quinazolin-4(3H)-one fragment. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2021;45:116330

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy induced DNA damage response: convergence of drugs and pathways. Cancer Biol. Ther.. 2013;14(5):379-389.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design and synthesis of 7-diethylaminocoumarin-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives with anti-acetylcholinesterase activities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res.. 2021;23(9):866-876.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydroxide-Mediated SNAr rearrangement for synthesis of novel depside derivatives containing diaryl ether skeleton as antitumor agents. Molecules. 2023;28(11):4303.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives possessing 1,4-benzodioxan moiety as potential anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2011;19(21):6518-6524.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The mechanism of triptolide in the treatment of connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Ann. Med.. 2022;54(1):541-552.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105386.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1