Translate this page into:

Synthesis, characterization, antibacterial studies and quantum-chemical investigation of the new fluorescent Cr(III) complexes

⁎Corresponding author. mehdipordel58@mshdiau.ac.ir (Mehdi Pordel)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Coordination of the ligands derived from benzimidazole with Cr(III) led to the formation of new fluorescent Cr (III) complexes. The structures of the new complexes were established by spectral, analytical data and Job’s method and an octahedral geometry was proposed for the complexes. Also, the DFT methods were employed to gain a deeper insight into geometry and spectral properties of the new Cr (III) complexes. The DFT-calculated vibrational modes of Cr(III) complexes are in good agreement with the experimental values, confirming suitability of the optimized geometries for the complexes. Fluorescent ligands and chromium complexes were spectrally characterized by UV–Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy. Results revealed that Cr(III) complexes generate fluorescence in dilute solution of DMSO. Calculated electronic absorption spectra were also provided by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) method. The new complexes exhibited potent antibacterial activity against a panel of strains of Gram negative bacterial and Gram positive species and their MIC was also determined. Two strains of Gram positive and two strains of Gram negative bacteria.

Keywords

Benzimidazole

Cr(III) complex

UV–Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy

DFT

Antibacterial activity

1 Introduction

The search for new antibacterial compounds continues to be very active because the resistance to the antibacterial agents is nowadays recognized as a major global public health problem.

The Cr chemicals play an important role in several industrial processes such as leather tanning, mining of chrome ore, production of steel and alloys, dyes and pigment manufacturing, glass industry, wood preservation, textile industry, film and photography, metal cleaning, plating and electroplating, etc. (Sarin et al., 2006). Chromium (III) is a significant bio-element responsible for many catalytic processes in living systems (Mandina and Tawanda, 2013). It is present in the active centers of many enzymes, which is why it is classified as one of the essential elements. It facilitates the transport of glucose from the blood to the cells (Chen et al., 2009) and cooperates with insulin in protein synthesis (Ziegenfuss et al., 2017). Cr(III) has been shown to have a detrimental effect on various components of the immune system, giving rise to immune stimulation or immune inhibition (Adam et al., 2017). Chromium(III) also plays an important function in lipid metabolism thus reducing the risk of atherogenesis (Chen et al., 2017), increase in lean body mass (Liu et al., 2015), and promotion of weight loss (Whitfield et al., 2016). Chromium(III) chelates have been found to interact with biological systems and to exhibit antineoplastic activity (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2017) and antibacterial, antifungal (Ghssein and Matar, 2018; El-Megharbel and Refat, 2015), and anticancer activity (Mahmoud et al., 2015). Some chromium (III) N,S,O/N,N-donor chelators are good anticancer agents due to strong binding ability with DNA base pair (Zhou et al., 2016).

On the other hand, benzimidazole nucleus is one of the most important heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. Owing to the great structural diversity of biologically active benzimidazole, it is not surprising that the benzimidazole nucleus has become a significant structural component in many pharmaceutical agents. Benzimidazole can be found in a wide range of bioactive compounds such as antiparasitics (Flores-Carrillo et al., 2017), anticonvulsants (Siddiqui et al., 2016), analgesics (Siddiqui et al., 2016), antihistaminics (Ding et al., 2017), antiulcers (Saini et al., 2016), antihypertensives (Zhang et al., 2015), antiviral (Vausselin et al., 2016), anticancers (Kumar et al., 2016), antifungals (Keller et al., 2015), anti-inflammatory agents (Gaba et al., 2014), proton pump inhibitors (Van Oosten et al., 2017) and anticoagulants (Yang et al., 2016). Optimization of substituents around the benzimidazole nucleus has resulted in many drugs like albendazole, mebendazole, thiabendazole as antihelmintics; omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole as proton pump inhibitors; astemizole as antihistaminic; enviradine as antiviral; candesarten cilexitil and telmisartan as antihypertensives and many lead compounds in a wide range of other therapeutic areas. Also, benzimidazoles play an important role in determining the function of a number of biologically important metal complexes (Bansal and Silakari, 2012).

Since, chromium and benzimidazole play a key role in biological systems, it is important to study the interactions of benzimidazole ligands with chromium. This paper describes the synthesis, spectral and density functional theory (DFT) calculations of three new chromium (III) complexes of fluorescent heterocyclic ligands derived from benzimidazole. Antibacterial activities of the compounds against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species were also determined.

2 Experimental

2.1 Equipment and materials

Percentage of the Cr(III) was measured by using a Hitachi 2-2000 atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The 13C NMR (75 MHz) and 1H NMR (300 MHz) spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance DRX-300 spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm downfield from TMS as internal standard; coupling constant J is given in Hz. The FT-IR spectra were recorded as potassium bromide pellets using a Tensor 27 spectrometer and only noteworthy absorptions are listed. The mass spectrum was recorded on a Varian Mat, CH-7 at 70 eV and ESI mass spectrum was measured using a Waters Micromass ZQ spectrometer. Elemental analysis was performed on a Thermo Finnigan Flash EA microanalyzer. Absorption and fluorescence spectra were recorded on Varian 50-bio UV–Visible spectrophotometer and Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorophotometer. UV–Vis and fluorescence scans were recorded from 200 to 1000 nm. Melting points were obtained on an Electrothermaltype-9100 melting-point apparatus.

The microorganisms Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 were purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran and Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was isolated from different specimens which were referred to the Microbiological Laboratory of Ghaem Hospital of Medical University of Mashhad, Iran and its methicillin resistance was tested according to the NCCLS guidelines.

All solvents were dried according to standard procedures. Compounds 1 (Preston, 1990) and 3a,c (Rahimizadeh et al., 2009) were obtained according to the published methods. Other reagents were commercially available.

2.2 Computational methods

All of the calculations have been performed using the DFT method with the B3LYP functional (Lee et al., 1988) as implemented in the Gaussian 03 program package (Frisch and Et, 2003). The 6-311++G(d, p) basis sets were employed except for the Cr(III) where the LANL2DZ basis sets were used with considering its effective core potential. Geometry of the Cr(III) complexes was fully optimized, which was confirmed to have no imaginary frequency of the Hessian. Geometry optimization and frequency calculation simulate the properties in the gas/solution phases.

The fully-optimized geometries were confirmed to have no imaginary frequency of the Hessian.

The solute-solvent interactions have been investigated using one of the self-consistent reaction field methods, i.e., the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) (Tomasi and Cammi, 1995).

2.2.1 General procedure for the synthesis of ligands 4a-c from 3a-c

To a solution of 3a-c (6 mmol) in EtOH (40 mL) and HCl (2 M, 3 mL), iron powder (0.89 g, 16 mmol) was added with stirring. Then, the mixture was refluxed for 4 h and then poured into water. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with water, and air-dried to give crude 4a-c.

(5-Amino-1-ethyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-4-yl)(phenyl)methanone (4a, L1) was obtained as a shiny yellow needles (EtOH). mp.: 186–188 °C [Lit mp. 185–187 °C] (Rahimizadeh et al., 2009); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.51 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.89 (br s, 2H, NH2), 4.13 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 6.67 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.20–7.49 (m, 5H, Ar H), 7.78 (s, 1H, Ar H) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 41.9, 111.0, 114.2, 114.7, 125.3, 127.2, 127.6, 127.6, 129.2, 132.1, 135.8, 142.0, 195.7 (C⚌O) ppm. IR (KBr): 3317, 3260 cm−1 (NH2), 1633 cm−1 (C⚌O). MS (m/z) 279 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C16H15N3O (265.3): C, 72.43; H, 5.70; N, 15.84. Found: C, 72.66; H, 5.73; N, 16.03.

(5-Amino-1-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-4-yl)(phenyl)methanone (4b, L2) was obtained as a shiny yellow needles (EtOH). mp.: 122–124 °C [Lit mp. 121–123 °C] (Rahimizadeh et al., 2009); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.94 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.75–2.10 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.04 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 4.12 (br s, 2H, NH2), 6.62 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.11–7.52 (m, 5H, Ar H), 7.75 (s, 1H, Ar H) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 11.4, 23.2, 46.8, 111.3, 114.1, 114.8, 125.5, 127.1, 127.6, 127.9, 129.0, 132.3, 135.6, 142.2, 195.9 (C⚌O) ppm. IR (KBr): 3315, 3260 cm−1 (NH2), 1635 cm−1 (C⚌O). MS (m/z) 279 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C17H17N3O (279.3): C, 73.10; H, 6.13; N, 15.04. Found: C, 73.45; H, 6.15; N, 14.87.

(5-Amino-1-butyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-4-yl)(phenyl)methanone (4c, L3) was obtained as a shiny yellow needles. m.p.: 117–119 °C. Yield: 79%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.89 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.21–1.33 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.77–1.88 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.19 (br s, 2H, NH2), 4.31 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, NCH2), 6.67 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.09–7.47 (m, 5H, Ar H), 7.73 (s, 1H, Ar H) ppm; 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 13.7, 20.01, 33.1, 44.5, 110.8, 114.3, 114.6, 125.3, 127.1, 127.4, 127.8, 128.8, 132.5, 135.9, 142.0, 195.3 (C⚌O) ppm. IR (KBr): 3320, 3263 cm−1 (NH2), 1637 cm−1 (C⚌O). MS (m/z) 293 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C18H19N3O (293.4): C, 73.69; H, 6.53; N, 14.32. Found: C, 74.01; H, 6.57; N, 14.09.

2.2.2 General procedure for the synthesis of the complexes 5a-c from ligands 4a-c

Chromium(III) nitrate nonahydrate (0.25 gr, 1 mmol) was added to the yellow solution of ligand 4a-c (2 mmol) in aqueous metanolic solution (15 mL, MeOH, H2O, 10:90), resulting in color change to orange. The reaction was carried out for another 1 h at rt. The complex was isolated by evaporation of the solvent and washed with cold MeOH and then H2O.

[Cr(L1)2]N3O9·2(H2O) (5a): was obtained as an orange powder. mp. >300 °C (decomp). IR (KBr): 3389, 3250 cm−1 (NH2), 1628 cm−1 (C⚌O), ESI-MS (+) m/z (%): 582 [Cr(L1)2]3+. Anal. Calcd for C32H34CrN9O13 (804.2): C, 47.76; H, 4.26; N, 15.67; Cr, 6.46. Found: C, 47.93; H, 4.29; N, 15.83; Cr, 6.59.

[Cr(L2)2]N3O9·2(H2O) (5b): was obtained as an orange powder. mp. >300 °C (decomp). IR (KBr): 3363, 3257 cm−1 (NH2), 1629 cm−1 (C⚌O), ESI-MS (+) m/z (%): 610 [Cr(L2)2]3+. Anal. Calcd for C34H38CrN9O13 (832.2): C, 49.04; H, 4.60; N, 15.14; Cr, 6.24. Found: C, 49.28; H, 4.64; N, 15.29; Cr, 6.39.

[Cr(L3)2]N3O9·2(H2O) (5c): was obtained as an orange powder. mp. > 300 °C (decomp). IR (KBr): 3371, 3260 cm−1 (NH2), 1625 cm−1 (C⚌O), ESI-MS (+) m/z (%): 638 [Cr(L3)2]3+. Anal. Calcd for C36H42CrN9O13 (860.2): C, 50.23; H, 4.92; N, 14.65; Cr, 6.04. Found: C, 49.80; H, 4.89; N, 14.51; Cr, 6.31.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and structure of the new ligands 4a-c and complexes 5a-c

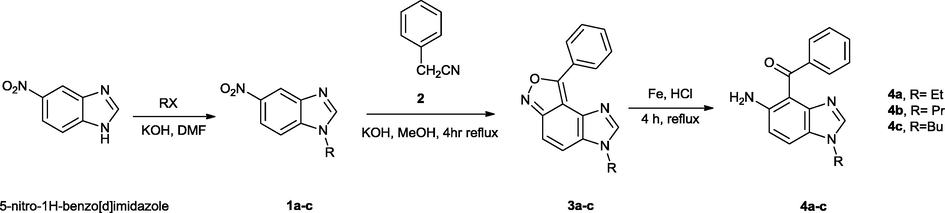

5-Nitro-1H-benzimidazole was alkylated with different alkyl halides in KOH and DMF according to the literature method (Preston, 1990). Reaction of compounds 1a-c with benzyl cyanide (2) in basic MeOH solution led to the formation of 3-alkyl-8-phenyl-3H-imidazo[4′,5′:3,4]benzo[1,2–c]isoxazole (3a-c) (Rahimizadeh et al., 2009). Aryl ketons 4a-c were obtained by reduction of compounds 3a-c in EtOH by Fe/HCl in high yields (Scheme 1).

Synthesis of the ligands 4a-c.

1H, 13C NMR, FT-IR spectra and analytical data proved the structure of the compounds 4a-c. For example, in the 1H NMR spectrum of compound 4c there is an exchangeable peak at δ 4.19 ppm attributed to NH2 group protons. Also, there are two doublet signals (δ = 6.67 and 7.01 ppm), a multiplet signal (δ = 7.09–747 ppm) and singlet signal (δ = 7.73 ppm) assignable to eight aromatic rings protons. In addition, 16 different carbon atom signals are observed in the 13C NMR spectrum of compound 4c. In addition, the FT-IR spectrum of compound 4c in KBr revealed a broad absorption bands at 3320 and 3263 cm−1 attributed to NH2 and 1637 cm−1 assignable to the C⚌O groups. Also, the results of mass spectroscopy (m/z 293 [M]+) and elemental analyses support the structure of the compound 4c.

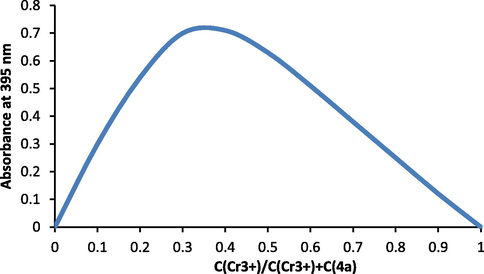

The new complexes 5a-c were obtained from reaction of ligands 4a-c and Cr(NO3)3·9H2O in 2:1 M ratio obtained by Job’s method (Fig. 1) (Vosburgh and Chromium, 1941) in aqueous metanolic solution. For example, the Job’s plot reached a maximum value at a mole fraction of 0.33, which confirmed that molar ratio between Cr(III) ions and 4a in the complex 5a is 1:2.

Job’s curve of equimolar solutions for complex 5a in aqueous methanolic solution.

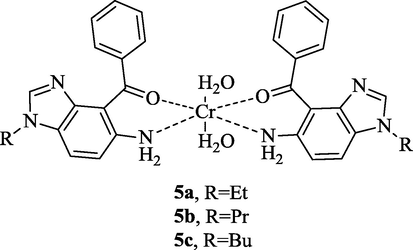

The structural assignments of the new complexes 5a-c were based on the elemental and spectroscopic (IR, and mass) analyses. The elemental analysis results for Cr complexes confirm the proposed [Cr(L)2]N3O9·2(H2O) formula. In addition, molecular ion peak at m/z 582 ([Cr(L1)2]3+), m/z 610 ([Cr(L2)2]3+) and m/z 638 ([Cr(L3)2]3+) strongly support the structure of the new complexes 5a, 5b and 5c respectively.

An octahedral geometry was proposed for Cr(III) complexes (5a-c) based on our experimental results and reported literatures (Yousefi et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015) (see Scheme 2).

The structure of the new Cr(III) complexes 5a-c.

The calculated data could help to gain a deeper insight into geometry and spectral properties of the new Cr (III) complexes. Therefore, geometry of Cr(III) complex (5a) were optimized in both of the gas phase and MeOH as the solvent (PCM model) by DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) level. The optimized geometry of the complex 5a is depicted in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data). Some of the calculated structural parameters of the Cr(III) complex are listed in Table S1 (Supplementary Data). As can be seen in Fig. S1 (Supporting Information), the ligand 4a acts as a bidentate ligand and coordinates to the Cr(III) via nitrogen atom of the amine functional group and oxygen atom of the carbonyl group. The aromatic rings of the ligand are in a same plane. The other position of the complex is filled by two H2O molecules. Also, optimized geometry and frequency calculations were done in both of the possible states of the complex, high spin and low spin. The high spin state of the complex is more stable than the low spin state. Their energy difference is 84.23 and 67.12 kJ. Mol−1 in the gas phase and PCM model, respectively.

The DFT computed vibrational modes of Cr(III) complex 5a are listed in Table 1 together with the experimental values for comparison. The atoms are numbered as in Fig. 2. As seen in Table 2, there is good agreement between the experimental and DFT-calculated frequencies of the complex 5a, confirming validity of the optimized geometry as a proper structure for the complex 5a. Abbreviation: op, out-of-plane; ip, in-plane; w, weak; m, medium; s, strong; vs, very strong; br, broad; sh, shoulder.

Experimental frequencies

Calculated

Frequency

IR Intensity

D (10−4 esu2 cm2)Vibrational assignment

703 (w)

691

159

υsym(Cr—N)

714 (w)

725

67

υasym(Cr—N)

967 (m)

982

210

δop(C—H) aromatic

1265 (m)

1261

110

υ(C1—N3, C22—N6)

1399 (m)

1406

1732

υasym(C4—C5—N2) + υasym(C25—C26—N5)

1451(s)

1413

519

υ(C = C, C⚌N) of the aromatic rings

1459

52

υ(C21—C9) + υ(C42—C30)

1467

310

υ(C⚌N) of the aromatic rings + υ(C42—N4, C21—N1)

1473

72

υ(C⚌N) of the aromatic rings + υ(C22—N6, C1—N3)

1630 (s)

1523

529

υ(C⚌C) of the aromatic rings

1564

4123

δsci(H—O—H) of the H2O ligands

1639

321

υ(C⚌C) of the benzene rings

1656

45

υ(C⚌C) of 1 moiety

2822 (m)

3069–3195

25–17

υsym(C—H) aliphatic

3082–3119

35–9

υasym(C—H) aliphatic

3189–3233

11–9

υ(C—H) aromatic

3375 (vs,br)

3555

45

υ(C28—H21)) + υ(C7—H2)

3783

19

υsym(O—H) of the H2O ligands

3877

39

υasym (O—H) of the H2O ligands

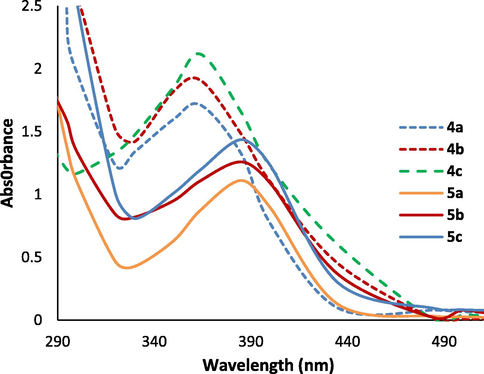

The absorption spectra of se 4a-c and Cr(III) complexes 5a-c in DMSO solution (10−4 M).

Dye

4a

4b

4c

5a

5b

5c

λabs (nm)a

360

365

365

395

395

400

ε × 10−3 [(mol L−1)−1 cm−1]b

15.9

18.2

22.2

11.1

12.6

14.4

λflu (nm)c

525

525

525

530

530

530

ΦFd

0.69

0.66

0.73

0.79

0.81

0.80

Based on the optimized geometries and using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) (Bauernschmitt and Ahlrichs, 1996) methods, the electronic spectrum of the complex 5a was predicted (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data). The TD-DFT electronic spectra calculations on 5a show a broad peak at 387 nm (oscillator strength: 0.4607), which can be linked to Ligand to-Metal charge transfer (LMCT) (Purwoko and Hadisaputra, 2017) transitions. This electronic transition band can be compared with the experimental value of 395 nm.

3.2 Photophysical properties of the ligands and complexes

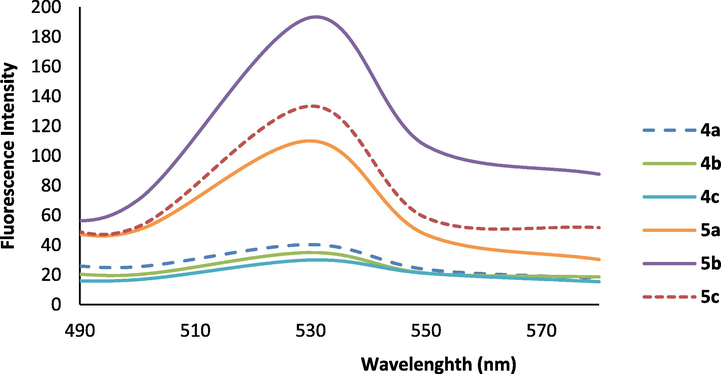

UV–Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy in the wavelength range of 200–1000 nm were applied to characterize the absorption and fluorescence emission spectra of fluorescent heterocyclic ligands 4a-c and Cr (III) complexes 5a-c (Figs. 2 and 3). Numerical spectral data are also presented in Table 2. Values of extinction coefficient (ε) were calculated as the slope of the plot of absorbance vs concentration. As seen in Fig. 2, the spectra of the complexes 5a-c have an absorption maximum at 402 nm at which the ligands have no absorbance. An efficient charge transfer of electron from p-orbital on ligand to Cr(III) d-orbital can be considered as the main reason for the color of the complexes explained as Ligand to-Metal charge transfer (LMCT) (Purwoko and Hadisaputra, 2017). Furthermore ligands 4a-c; and chromium complexes 5a-c produced fluorescence in dilute solution of DMSO (Fig. 2). The fluorescence quantum yields of the compounds were also determined via comparison methods, using fluorescein as a standard sample in 0.1 M NaOH and MeOH solution (Umberger and LaMer, 1945). The used value of the fluorescein emission quantum yield is 0.79 and the obtained emission quantum yields of the new compounds are around 0.66–0.81. As can be seen from Table 2, extinction coefficient (ε) of 4c, fluorescence intensity and the emission quantum yield in 5b were the biggest values.

The fluorescence emission spectra of 4a-c and Cr(III) complexes 5a-c in DMSO solution (1 × 10−6 M).

3.3 Antibacterial studies

The antibacterial activity of the compounds 4a-c and 5a-c was tested against a panel of strains of Gram negative bacterial (Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) and Escherichia coli, (ATCC 25922)) and Gram positive (Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA)) clinical isolated and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633)) species (Table 3) using broth microdilution method as previously described (Espinel-Ingroff et al., 2015). Comparison with Ampicillin as a standard was done. The lowest concentration of the antibacterial agent that prevents growth of the test organism, as detected by lack of visual turbidity (matching the negative growth control), is designated the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Experimental details of the tests can be found in our earlier study (Pordel et al., 2013).

Compds.

S.a. (MRSA)

B.s. (ATCC 6633)

P.a. (ATCC 27853)

E.c. (ATCC 25922)

4a

110

95

90

95

4b

95

90

80

80

4c

90

90

80

80

5a

35

30

30

25

5b

25

15

15

15

5c

10

5

10

5

Ampicillin

62

0.50

125

8

As can be concluded from Table 3, compounds 4a-c inhibit the metabolic growth of the tested Gram positive and negative bacteria to the same extent, but the inhibitions percent are less than those of Ampicillin. Coordination of ligands 4a-c to Cr(III) leads to improvement in the antibacterial activity. This can be explained by Tweedy’s chelation theory (Tweedy, 1964), which explicated that the lipophilicity of the uncoordinated ligand can be changed by reducing of the polarizability of the Mn+ ion via the L → M donation, and the possible electron delocalization over the metal complexes. Also, the results revealed that the complex 5c with R = Bu group, showed greater antibacterial activity against S.a. (MRSA), P.a. (ATCC 27853) and E.c. (ATCC 25922) than did the well known antibacterial agent Ampicillin (Table 3). Considering the selectivity of the action of new compounds, they were applied to normal HDF cells (a category of human skin fibroblasts) and did not show significant toxicity up to 100 mg/l.

4 Conclusion

New fluorescent Cr (III) complexes were obtained from coordination of the ligands derived from benzimidazole with Cr(III) cation. The structures of the ligands and complexes have been established by spectral and analytical data and an octahedral geometry was proposed for the complexes. To gain a deeper insight into geometry and spectral properties of the new complexes, the DFT methods were employed. The DFT-calculated vibrational modes of Cr(III) complexes are in good agreement with the experimental values, confirming suitability of the optimized geometries for the complexes. Fluorescent ligands and chromium complexes were spectrally characterized by UV–Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy. Results revealed that Cr(III) complexes generate fluorescence in dilute solution of DMSO. Also, results from the antimicrobial screening tests revealed that an improvement in the antibacterial activity is observed upon the coordination of the ligands to the Cr(III) ion and the new complexes are more effective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) species than did Ampicillin. This activity, together with high fluorescence intensity, can offer an opportunity for the study of physiological functions of bacteria such as at single-cell level (Joux and Lebaron, 2000).

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Research Office, Mashhad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad-Iran, for financial support of this work. We must also acknowledge Maryam Jajarmi (Khorasan Razavi Rural Water and Wastewater Co.) for her assistance in antibacterial studies.

References

- DNA interaction, antimicrobial, anticancer activities and molecular docking study of some new VO (II), Cr (III), Mn (II) and Ni (II) mononuclear chelates encompassing quaridentate imine ligand. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Biol.. 2017;170:271-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allergy-inducing chromium compounds trigger potent innate immune stimulation via ROS-dependent inflammasome activation. J. Inv. Derm.. 2017;137:367-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- The therapeutic journey of benzimidazoles: a review. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2012;20:6208-6236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 1996;256:454.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromium supplementation enchances insulin signaling in skeletal muscle of obese KK/HIJ diabetic mice. Diabet. Obesity Metabol.. 2009;11:293-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of chromium picolinate on fat deposition, activity and genetic expression of lipid metabolism-related enzymes in 21 day old Ross broilers. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 2017

- [Google Scholar]

- Benzimidazole derivative M084 extends the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans in a DAF-16/FOXO-dependent way. Mol. Cell. Biochem.. 2017;426:101-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ligational behavior of clioquinol antifungal drug towards Ag (I), Hg (II), Cr (III) and Fe (III) metal ions: synthesis, spectroscopic, thermal, morphological and antimicrobial studies. J. Mol. Struct.. 2015;1085:222-234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multicenter study of isavuconazole MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex using the CLSI M27–A3 broth microdilution method. Antimicro. Chemother.. 2015;59:666-668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, antiprotozoal activity, and chemoinformatic analysis of 2-(methylthio)-1H-benzimidazole-5-carboxamide derivatives: identification of new selective giardicidal and trichomonicidal compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017

- [Google Scholar]

- Gaussian 03, Revision B.03. Pittsburgh, PA: Gaussian Inc; 2003. p. :1101.

- Benzimidazole: an emerging scaffold for analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2014;76:494-505.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chelating mechanisms of transition metals by bacterial metallophores “Pseudopaline and Staphylopine”: a quantum chemical assessment. Computation. 2018;6:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteriaat single-cell level. Microbes infect.. 2000;2:1523-1535.

- [Google Scholar]

- An antifungal benzimidazole derivative inhibits ergosterol biosynthesis and reveals novel sterols. Antimicro. Chem.. 2015;59:6296-6307.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cationic Ru (II), Rh (III) and Ir (III) complexes containing cyclic π-perimeter and 2-aminophenyl benzimidazole ligands: synthesis, molecular structure, DNA and protein binding, cytotoxicity and anticancer activity. J. Org. Chem.. 2016;801:68-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785-789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure, photochemistry and magnetic properties of tetrahydrogenated Schiff base chromium (III) complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spect.. 2015;140:437-443.

- [Google Scholar]

- A dietary supplement containing cinnamon, chromium and carnosine decreases fasting plasma glucose and increases lean mass in overweight or obese pre-diabetic subjects: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Plos One. 2015;10:e0138646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural characterization, in vitro antimicrobial and anticancer activity studies of ternary metal complexes containing glycine amino acid and the anti-inflammatory drug lornoxicam. J. Mol. Struct.. 2015;1082:12-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromium, 2013. an essential nutrient and pollutant. Afr. J. Pure. Appl. Chem.. 2013;30:310-317.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel isoxazolo[4,3-e]indoles as antibacterial agents. Rus. J. Bioorg. Chem.. 2013;39:211-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- In The Chem. Hetero. Comp.. 1990;40:87-105.

- Experimental and theoretical study of the substituted (Η6-Arene) Cr (CO) 3 complexes. Orien. J. Chem.. 2017;33:717-724.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of a new heterocyclic system—Fluoreno[1,2-d]imidazol-10-one. Can. J. Chem.. 2009;87:724-728.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antioxidant activity of the 2-methyl benzimidazole. J. Drug Del. Thera.. 2016;6:100-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamic and breakthrough column studies for the selective sorption of chromium from industrial effluent on activated eucalyptus bark. Bioresour. Techonol.. 2006;97:1986-1993.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of new benzimidazole and phenylhydrazinecarbothiomide hybrids and their anticonvulsant activity. Med. Chem. Res.. 2016;25:1390-1402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antidepressant, analgesic activity and SAR studies of substituted benzimidazoles. As. J. Pharm. Res.. 2016;6:170-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Remarks on the use of the apparent surface charges (ASC) methods in solvation problems: Iterative versus matrix-inversion procedures and the renormalization of the apparent charges. J. Comput. Chem.. 1995;16:1449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant extracts with metal ions as potential antimicrobial agents. Phytopathology. 1964;55:910-914.

- [Google Scholar]

- The kinetics of diffusion controlled molecular and ionic reactions in solution as determined by measurements of the quenching of fluorescence. J. Am. Chem.. 1945;67:1099.

- [Google Scholar]

- A benzimidazole proton pump inhibitor increases growth and tolerance to salt stress in Tomato. Front. Plant. Sci.. 2017;2017:8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of a new benzimidazole derivative as an antiviral against hepatitis C virus. J. Virol.. 2016;90:8422-8434.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complex ions. I. The identification of complex ions in solution by spectrophotometric measurements. J. Am. Chem.. 1941;63:437.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of a, loss and lipid parameters in type 2 diabetes: an open-label cross-over randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. nut.. 2016;55:1123-1131.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and anticoagulant bioactivity evaluation of 1,2,5-trisubstituted benzimidazole fluorinated derivatives. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ.. 2016;32:973-978.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the influence of crystal environment on the geometry of bis(pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylato) chromium (III) anionic complexes containing various cationic moieties: synthesis, structures and Hirshfeld surface analysis. J. Mol. Struc.. 2015;1083:460-470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel NO-releasing benzimidazole hybrids as potential antihypertensive candidate. Chem. Bio. D. Des.. 2015;85:541-548.

- [Google Scholar]

- Binding to DNA backbone phosphate and bases: slow ligand exchange rates and metal hydrolysis. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2016.Cr3+;55:8193-8200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of an amylopectin and chromium complex on the anabolic response to a suboptimal dose of whey protein. J. Inter. Soc. Sp. Nut.. 2017;14:6.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2019.03.001.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1