Translate this page into:

Synthesis, characterization, biological and docking studies of ZrO(II), VO(II) and Zn(II) complexes of a halogenated tetra-dentate Schiff base

⁎Corresponding author. laila.abdelrahman@science.sohag.edu.eg (Laila H. Abdel-Rahman)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The new Schiff base ligand 2,2′-{(4-chloro-1,2-phenylene)bis(nitrilo(E)methylylidene)}bis(4-bromophenol) (H2L) and its VO(II), Zn(II) and ZrO(II) metal chelates have been synthesized and characterized by spectral, powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD), molar conductance, magnetic measurements, thermal and elemental analyses. The molecular geometry of the prepared compounds has been confirmed by applying the theoretical density functional theory calculations (DFT). The analytical data showed that the parent azomethine H2L ligand binds to the VO(II), Zn(II) and ZrO(II) ions through both of the two azomethine-N and two phenolic-O groups and adopts distorted octahedral geometry for ZnL(H2O)2 chelate while square pyramidal geometries for VOL and ZrOL chelates. The antioxidant activity of the compounds was also evaluated by using 1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picrylhydrazyl (DDPH) reduction method and compared with the positive control ascorbic acid. Carcinoma cells such as breast (MCF-7), liver (Hep-G2), colon (HCT-116) carcinoma cell lines and human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK-293) were used for in vitro cell proliferation to investigate the anticancer potency of the prepared compounds. The results showed that, the tumor growth is inhibited and dose-dependent according to the following order: VOL > ZrOL > ZnL(H2O)2 > H2L. The titled compounds have been also tested for their antimicrobial activity against certain pathogenic bacteria and fungi. The results showed that the H2L ligand and its complexes has enhanced antibacterial and antifungal activities. The CT-DNA binding experiments of azomethine chelates showed that, the binding modes are intercalative, and the determined intrinsic binding constants (Kb) for the VOL, ZrOL, ZnL(H2O)2 complexes, are in the range 6.1–7.8 × 105 mol−1 dm−3.

The docking calculations were performed to probe the nature of binding affinity of the synthesized compounds with human DNA (PDB:1bna). The compounds may be applicable orally in an accurate manner, according to their in-silico intake, delivery, metabolic processes, digestion, and toxic effects (ADME) data.

Keywords

Schiff base complexes

DNA interaction

Antimicrobial

Cytotoxicity

Antioxidant activity

Docking

ADMET study

1 Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020 (Ferlay et al., 2020). Platinum-based metal complexes have long been utilized as anti-cancer medications all over the world (Thangavel et al., 2018). Cisplatin, a chemotherapy drug used to treat a variety of tumors, is extremely expensive and has substantial side effects (Oun et al., 2018; Suna et al., 2019). The severe side effects, toxicity, and resistance of platinum-based therapeutic compounds in living cells continue to be a major concern, prompting the development of new anti-cancer medications that do not contain platinum (Liang et al., 2017). Meanwhile, several forms of antibiotic-resistant bacteria have spread in recent years. To counter the tremendous antibiotic resistance in our community, we need to discover new classes of antimicrobials (Lapasam et al., 2019). Tetra-dentate Schiff bases with a N2O2 donor atom are flexible ligands for the synthesis of numerous transition metal complexes and have a wide range of applications in both organic and inorganic Fields (Haak et al., 2010; Budige et al., 2011; Rajput et al., 2017). Their metal complexes exhibit effective antimicrobial (Bartyzel, 2013), antioxidant (Liu et al., 2009), antitumor (Rajput et al., 2016), anti-inflammatory (Bekhit et al., 2008) and DNA cleavage (Neelakantan et al., 2008). Schiff bases have attracted the attention of scientists due to their wide range of applications. Many researches reported that Schiff bases ligands with halo-atoms are one of the most widely used classes of ligands in a broad range of pharmacology, biochemistry, and physiology (Buldurun et al., 2019; Bharti et al., 2017). Due to the structural characteristics of Schiff base metal complexes bearing halogen groups, they have been recognized as a vital drug for a wide range of diseases such as anti-diabetes (Yeyea et al., 2020), antimicrobial (Sahraei et al., 2017), anti-cancer (Sankarganesh et al., 2019), anti-inflammatory (Lakshman et al., 2019), and cardiovascular (Crichton et al., 2008) diseases. This attributed to binding activity of the metal ions and to build new coordination architectures through strong and weak hydrogen bonds as well as π-π stacking interactions (El-Sherif and Eldebss, 2011). The use of DNA binding activity in the design and development of advanced drugs is an exciting and ongoing research area (Kazemi et al., 2015). The presence of halogens in the ligands structure has some advantages such as increased binding affinity, membrane permeability, and oral absorbability (Ariyaeifar et al., 2018). The effect of halide substituents on biological activities, particularly the essential role of a halogen atom in drugs, has been discussed (Kubanik et al., 2015; Tabatabaei-Dakhili et al., 2019). Azomethine oxovanadium complexes in particular have been found to be strongly active, against some types of Leukemia, insulin enhancing agents, antimicrobial, anti-tumoral and anti-tuberculosis (Al-Nuzal and Al-Amery, 2016; Turan et al., 2016; Scalese et al., 2017). Zirconium complexes displayed different tumor progression for a wide variety of mouse and human carcinomas with reduced toxicity compared to cisplatin (Abdolmaleki et al., 2018). Due to their bactericidal, anti-inflammatory, anti-depressant, anti-diabetic, anti-allergic, and anti-carcinogenic activities, zinc Schiff base complexes are used in multiple purposes as drugs (Mondal et al., 2017). From the medical point of view, the aim of the incurrent study is to prepare new VO(II), Zn(II), and ZrO(II) halogenated N2O2 imine complexes and to study their cytotoxic, antioxidant, antimicrobial activities, and its DNA interaction ability. Besides, to validate the biological findings from the experimental study molecular modeling studies were done to classify the potential binding modes of the compounds with the most active human DNA receptor site. Therefore, in light of above findings, we herein report a new synthetic route of the title ligand as a water-insoluble Schiff base and its complexes, as a new series, and discussed their stoichiometric ratio, thermal stability, cytotoxicity, antioxidant activity, anti-pathogenic activities, DNA binding, PXRD, and density functional theory calculations.

2 Experimental

The supplementary materials provide information of the reagents, apparatus and procedures used in this work.

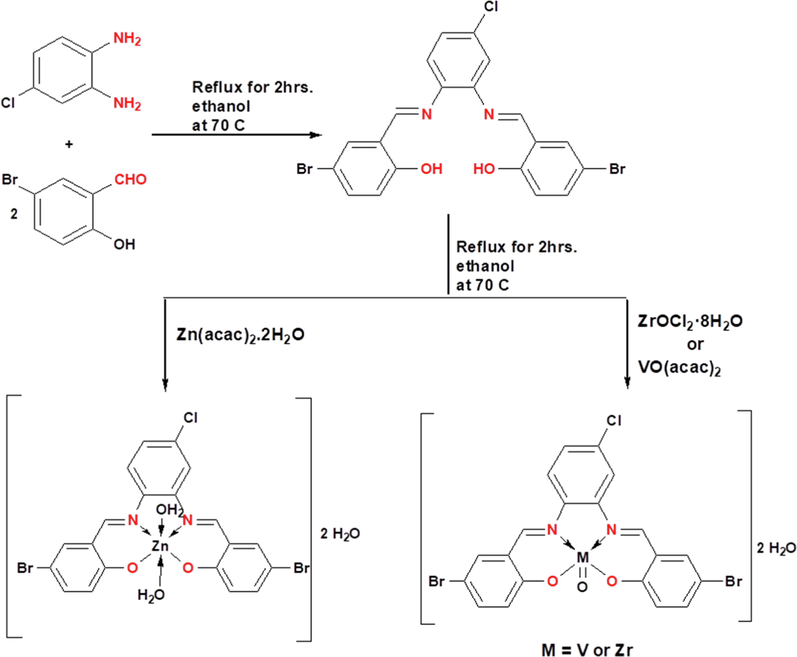

2.1 Synthesis of the H2L ligand

The tested H2L ligand was prepared by adding a solution of (0.71 g; 5 mmol) 4-chloro-o-phynelendiamine in 20 mL hot ethanol in dropwise with continuous stirring to a solution of 5-bromo-salicyaldehyde (2.01 g; 10 mmol) in 20 mL hot ethanol too. The reaction mixture was left under reflux for 2 h at 70 °C. The resulting deep orange solid was filtered off, purified by washing several times with diethyl ether and recrystallized by ethanol.

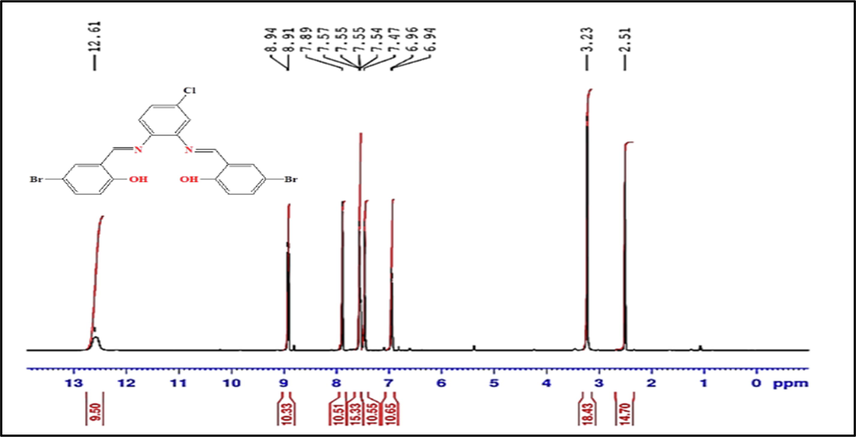

Yield 76%; deep orange color; m. p 190 °C. FT-IR (KBr, cm−1): 1614 (C═N), 3443 (─OH). 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 12.61 (s, 2H, 2OH), 8.94–8.91 (s, 2H, 2N=CH), 7.89–6.94 (m, 9H, 9CHar). 13C NMR (DMSO‐d6, δ, ppm): 110.47 (CH), 115.14 (CH), 117.70 (CH), 118.81 (CH), 119.97 (CH), 120.39 (CH), 123.15 (CH), 125.27 (CH), 129.31 (CH), 131.08 (CH), 131.77 (CH), 133.82 (CH), 134.55 (Cq, CH-N), 134.78 (Cq, CH-N), 138.92 (Cq, CH-OH), 154.77 (Cq, CH-OH), 157.40 (Cq, CH-CH=N), 160.30 (Cq, CH-CH = N), 190.28 (2CH=N). Anal. Calc. for C20H13Br2ClN2O2 (%); C, 47.24; H, 2.56; N, 5.51. Found (%): C, 47.18; H, 2.61; N, 5.46.

2.2 Synthesis of imine chelates

The imine chelates were synthesized by refluxing a mixture of (1.52 g; 3 mmol) of the H2L ligand, in 20 mL hot ethanol with an individual solutions of the salts in 20 mL of an aqueous ethanolic solution. [Thus: ZrOCl2⋅8H2O (3 mmol and 0.97 g), VO(acac)2 (0.79 and 3 mmol)] and Zn(acac)2⋅2H2O (3 mmol and 0.66 g) frequently for 2 hrs. at 70 °C with magnetic stirring in separated flasks. The reaction mixtures were left to evaporate at room temperature for 48 h where the solid complexes were separated. The colored metal complexes were filtered off, washed several times with diethyl ether and recrystallized by ethanol. The purity of the new complexes was determined by TLC. Scheme 1 provides the synthetic methodology for the titled compounds.

Synthetic strategy for the preparation of the H2L ligand and its complexes.

2.2.1 Analysis of ZrOL complex

Dark green solid; Yield 73%; Dec. temp. < 300 °C. FT‐IR (KBr, cm−1): 1608 (C═N), 486 (M−N), 533 (M−O). 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 9.20–9.17 (s, 2H, 2 N = CH), 8.80–8.05 (m, 3H, 3CHar), 7.79–7.56 (m, 3H, 3CHar), 7.06–6.76 (m, 3H, 3CHar). Anal. Calc. for C20H15Br2ClN2O5Zr (%): N, 4.31; C, 36.92; H, 2.31. Found (%):N, 4.27; C, 37.00; H, 2.37. μeff (B. M.): diamagnetic. Λm: 2.5 Ω−1 mol−1 cm2.

2.2.2 Analysis of VOL complex

Brown solid in yield: 71%. Dec. temp. < 300 °C. FT‐IR (KBr, cm−1): 1604 (C═N), 516 (M−N), 560 (M−O). Anal. Calc. for C20H15Br2ClN2O5V (%): N, 4.60; C, 39.40; H, 2.46. Found (%): N, 4.55; C, 39.35; H, 2.40. μeff (B. M.): 1.77B. M. Λm: 4.8 Ω−1 mol−1 cm2.

2.2.3 Analysis of ZnL(H2O)2 complex

Green in yield 72%; Dec. temp. < 300 °C. FT‐IR (KBr, cm−1): 1617 (C═N), 430 (M−N), 505 (M−O). 1H NMR (DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 9.06–9.02 (s, 2H, 2 N = CH), 8.03–7.90 (d, 2H, 2CHar), 7.61 (d, 2H, 2CHar), 7.49–7.31 (m, 3H, 3CHar), 6.69 (d, 2H, 2CHar). Anal. Calc. for C20H19Br2ClN2O6Zn(%): N, 4.35; C, 37.27; H, 2.95. Found (%):N, 4.42; C, 37.32; H, 2.91. μeff (B. M.): diamagnetic. Λm: 9.3 Ω−1 mol−1 cm2.

2.3 Calculation of the stoichiometric ratio of complexes and their apparent formation parameters

The easiest spectrophotometric technique for analyzing the equilibrium in solutions and the metal-to-ligand ratio is the molar ratio and continuous variation methodologies. For the 1:1 complex, the formation parameters (K f) of the prepared imine complexes have been inferred from spectrophotometric calculation according to the equation in our previous work (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2017; Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018). Moreover, the free energy change of the complexes ( ) was calculated utilizing the equation in our previous work (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018).

2.4 Theory/calculation

To examine the optimum geometry of the prepared compounds, Theory/calculation were performed at the B3LYP/GENECP level of theory, where C, H, N, O, Cl and Br atoms at 6-311G++(d, p) and metal atoms at LANL2DZ, using Gaussian 09 program (Frisch et al., 2010).

2.5 Biological studies

2.5.1 In vitro cytotoxicity

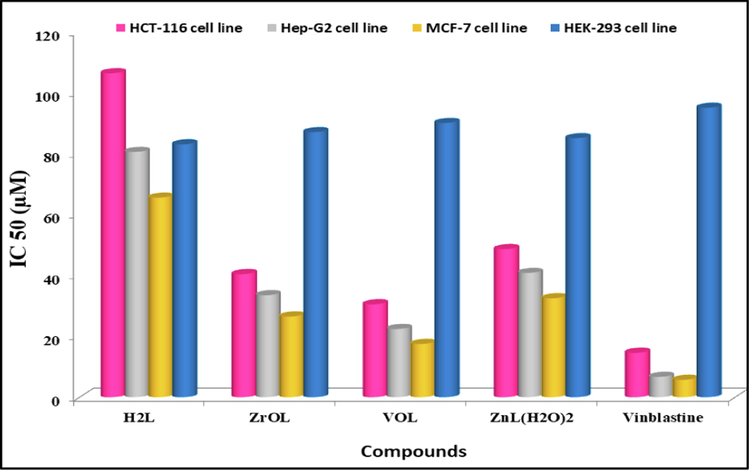

The synthesized H2L ligand and its imine chelates were tested for cytotoxicity towards human colorectal colon cancer (HCT-116 adenocarcinoma cell lines), normal cell line (HEK-293), breast cancer (MCF-7 adenocarcinoma cell lines) and hepatic cancer (HepG-2 adenocarcinoma cell lines). It was undertaken by utilizing sulfo-rhodamine-b-stain (SRB) assay that according to published methodology (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2017; Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018; Abu-Dief et al., 2021). Eventually, the results of prepared compounds are compared with those results of vinblastine as a positive control. From Eq. (1), the inhibitory concentration percentage was estimated.

2.5.2 Antioxidant activity

The DPPH assay was used according to the reported technique to test the anti-oxidant properties of prepared compounds (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2020a; Abu-Dief et al., 2021). It is an important route for checking the radical scavenging activity of specific compounds. The radical scavenging activities of DPPH were estimated at different concentrations of the synthesized compounds (10, 25, 50, 100 and 150 μM). Standard drug used is ascorbic acid (Vitamin C). The decrease in DPPH absorbance was determined in comparison with the control's measured absorbance. The anti-radical percent was determined according to the formula given:

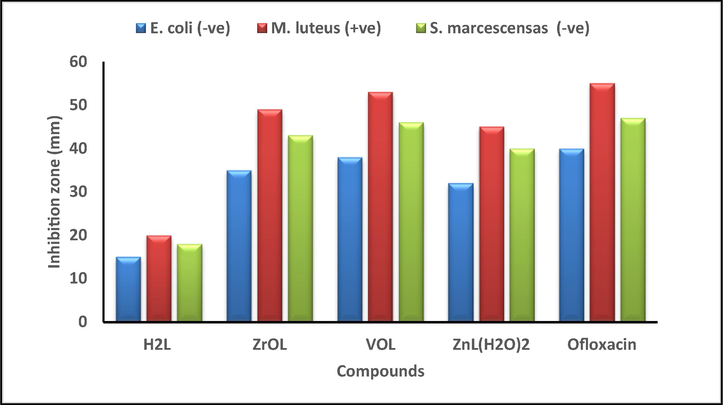

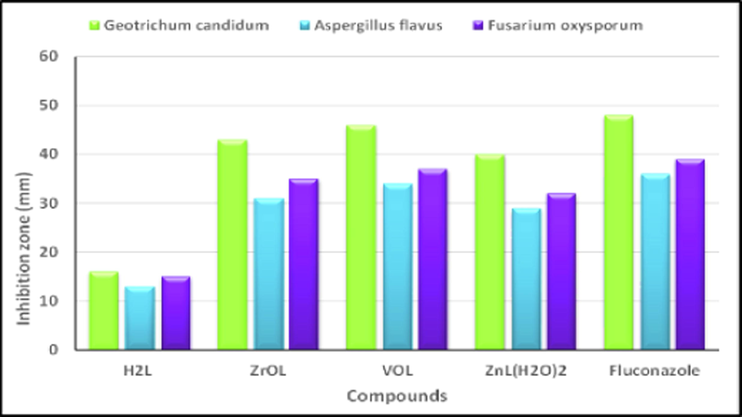

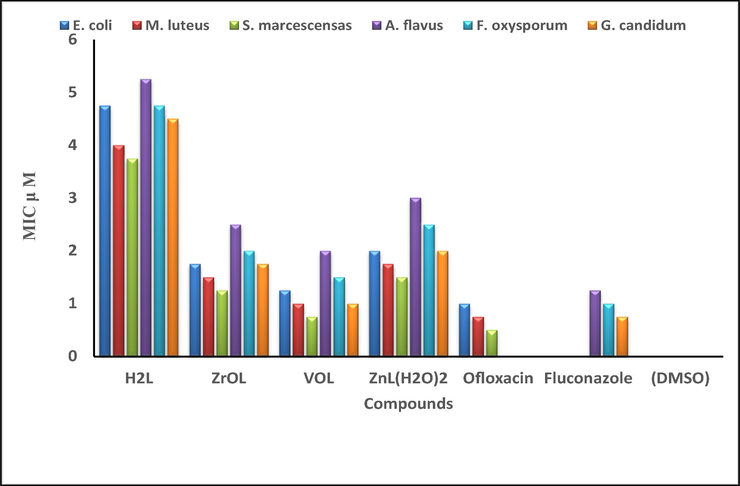

2.5.3 Anti-pathogenic activities

The prepared compounds were screened against Aspergillus flavus, Getrichm candida, Fusarium oxysporum, Serratia marcescens, Escherichia coli, Micrococcus luteus: The detailed procedure was previously reported (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018; Ramadan et al., 2018; Shukla et al., 2020). Principal technique was carried out by agar well diffusion at concentrations of 15 and 30 μM in DMSO. After incubation, 24 h at 37 °C for antibacterial activity and 72 h at 25 °C for antifungal activity using disc diffusion and microdilution assays, the antimicrobial potential was measured. The obtained data were compared with those of the ofloxacin antibacterial and fluconazole antifungal agent as positive controls. DMSO was used as negative control for anti-pathogenic activities. The inhibition zone against each organism was measured in triplicate sets and the average was reported. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of H2L imine, its metal complexes and the standards were examined against each studied organism utilizing broth dilution technique. Simple inhibition zones were estimated in mm and the percentage activity index was calculated as follows:

2.5.4 Investigation DNA binding with azomethine metal chelates

2.5.4.1 Spectrophotometric titrations

The association of synthesized complexes with CT-DNA in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution was determined using spectrophotometry (pH 7.2). Stock solutions of synthesized complexes were freshly prepared by dissolving them in DMSO to identify the binding affinity modes with CT-DNA and evaluate the binding constants (Kb) (Kargara et al., 2021). The UV absorption of CT-DNA solution exhibit a 260/280 ratio at 1.80, demonstrating that CT-DNA was sufficiently protein-free (Kazemi et al., 2017). The Spectrophotometric experiments were carried out by keeping constant concentration for all the complexes at 1

10−3 M, while the concentration of CT-DNA gradually increased. Using spectrophotometric titration data, the binding constants (Kb) of the listed complexes were determined by the Eq. (4) (Aboafia et al., 2018):

2.5.4.2 Viscosity strategy

The Oswald micro viscometer has been used to assess the relative viscoelastic properties of the interacting compounds. The hydrodynamic activity analysis between both new complexes and CT-DNA was conducted (Saleem et al., 2021). The derived viscosity of the prepared complexes (0–60 μM), in absence (η°) and in presence (η) of CT-DNA has been determined using Eq. (6) under inert conditions (N2 gas bubbling) (Rambabu et al., 2020).

2.5.4.3 Assay of gel electrophoresis

The appropriate technique to investigate the effect of the tested complexes on DNA is gel electrophoresis (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018; Adam and Elsawy, 2018; Chen et al., 2021). The stock solutions were produced in 1 × 10−3 M concentrations by dissolving the new complexes in DMSO. 10 μL of each mixture was transferred to 4 μL of DNA loading buffer after incubation of the mixtures of new complexes and CT-DNA for 1 hr. at 37 °C. Afterwards, we injected the mixture to chamber wells (1% agarose gel) submerged in the TBE buffer. The gel is tracked at 100 V in the electrophoresis tank for ∼45 min. The mobility of samples in agarose gel is recorded by taking photographs of Genius 3 Panasonic DMC-LZ5 Lumix.

2.5.5 MOE-docking procedure

From the Gaussian 09 (G09) software output, the structure of the titled ligand and its complexes were generated in PDB file format. The human DNA receptor Mol. Struct. (PDB ID:1BNA) has been downloaded from the PDB database (Pettersen et al., 2004).

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Physical properties

The colored H2L ligand (2,2′-{(4-chloro-1,2 phenylene)bis(nitrilo(E)methylylidene)}bis(4-bromophenol)) and its complexes were synthesized according to Scheme 1. Table 1 shows microanalysis measurements, stability constant (pK), formation constants (Kf) and free energy of Gibbs (ΔG≠) of the new ligand and its complexes.

Comp

M. F. (M.W.)

M. p. (°C)

Color

Λ m (Ω−1 cm2 Mol−1)

μ eff (B.M.)

Analysis (%) Found (calc.)

Kf x105

pK

ΔG* (kJ mol−1)

C

H

N

H2L

C20H13Br2ClN2O2

508190

Deep orange

–

–

47.18

(47.24)2.61

(2.56)5.46

(5.51)–

–

–

ZrOL

C20H15Br2ClN2O5Zr

650<300

Dark green

2.5

Dia.

37.00

(36.92)2.37

(2.31)4.27

(4.31)7.5

−5.87

–33.52

VOL

C20H15Br2ClN2O5V

609<300

Brown

4.8

1.77

39.35

(39.40)2.40

(2.46)4.55

(4.60)8.4

−5.92

–33.79

ZnL(H2O)2

C20H19Br2ClN2O6Zn

644<300

Green

9.3

Dia.

37.32

(37.27)2.91

(2.95)4.42

(4.35)6.7

−5.82

–33.24

The elemental analysis results showed that the ratio of metal to ligand is 1:1 and the structure form of each complex could be represented as ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 respectively, where L is the ligand. The molar conductance values given in Table 1, are less than 10 Ω−1 cm2 Mol−1 for the titled imine chelates indicating their non-electrolytic nature (Shiju et al., 2020). As seen in Table 1, the magnetic properties (μeff) were calculated at 298 K for the prepared imine complexes. For the VOL complex, the μeff value of 1.77 was revealed to have paramagnetic properties with square pyramidal structure attributable to the spin-only value for the d1 system (Yaul et al., 2017). Unlike the μeff of the ZrOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes, which were immeasurable, thereby indicate their diamagnetic characteristics with square pyramidal and distorted octahedral geometries, respectively.

3.1.1 Spectrophotometric determination of stoichiometry of chelates and their apparent stability constants.

The stoichiometry of the mentioned complexes is 1:1 for M: L molar ratio as displayed from continuous variation measurement in Supplementary Figure S1. Importantly, the studied complexes displayed the wide range of stability, as shown from the obtained formation constant values. This suggested that the new complexes are significantly stable than their Schiff base ligand which recommend the prospect of using the new complexes in multiple biochemical processes. The results of Gibbs free energy values displayed in Table 1 showed that the complex formation process is favorable and spontaneous (Al-Saeedi et al., 2018). Supplementary Figure S2 includes the curves of the mole fraction, is supporting the same metal ions to ligands ratio in the tested complexes.

3.1.2 Infrared spectra

To identify the coordination sites that may be involved in complexation, the IR spectra of the new chelates were compared with that of the H2L free ligand (Supplementary Figure S3-S6). The IR spectrum of the H2L ligand displays a strong and intense band at 1614 cm−1 owing to υ(C=N) of azomethine group. The υ(C=N) of the coordinated azomethine group of the ligand with our metal ions, was shifted to a lower wave number at 1608 for ZrOL and at 1604 cm−1 for VOL and at a higher wave number for ZnL(H2O)2 at 1617 cm−1. This indicating the involvement of the azomethine group in coordination to the metal center (Shanthalakshmi et al., 2017). The blue shift of the υ(C-O) band (appeared at 1276 cm−1 in the H2L ligand spectrum) is between 20 and 55 cm−1 in the spectra of the new complexes. This supports the participation of the phenolic OH group in complex formation. The participation of nitrogen and oxygen atoms in coordination with the metal ion is further verified by the appearance of new bands in the range 430–516 and 505–560 cm−1 attributed to υ (M−N) and υ (M−O), respectively (Adam et al., 2021). IR spectrum of ZnL(H2O)2 complex shows broad band at 3427 cm−1 which can be belonging to the two lattice water molecules (Atlam et al., 2020). The IR spectrum of the VOL complex displays a band at 970 cm−1, which is belonging to vibration of VO(II) in monomeric structure (Yaul et al., 2017; Abu-Dief et al., 2020). The IR spectrum of the ZrOL complex has a band at 967 cm−1, which is belonging to vibration of ZrO(II) in monomeric structure.

3.1.3 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR spectra

Using DMSO‑d6 as a solvent, and the chem. shift in ppm, the 1HNMR data for Schiff base was reported (Fig. 1). In 1HNMR spectrum of the H2L ligand, the signal of the two azomethine protons (HC = N) appeared at 8.94–8.91 ppm, while the signal of the two phenolic OH was detected at 12.61 ppm. Also, Fig. 1 displays the signals of the nine aromatic protons at 7.89–6.94 ppm. The bonding of intermolecular hydrogen is verified with the higher values of δ for the OH groups (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2020b). The 1H NMR spectra of ZrOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes show singlet signals at (9.20 and 9.17 ppm) and (9.06 and 9.02 ppm) referring to two azomethine protons, respectively, so the change of their position of signal indicates that it participates in forming chelates (Figure S7). Also, the signal of hydroxyl group disappeared in the spectra indicating its involvement in complexation.

The 1H NMR spectrum of the H2L ligand.

The 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of the prepared H2L ligand reveals a signal at 190.28 ppm, corresponding to two azomethine carbons (Supplementary Figure S8). The signals that occurred in 110.47–160.30 ppm are compatible with aromatic carbons as shown in its 13C NMR spectrum.

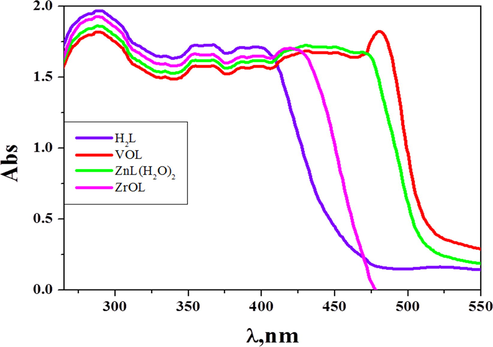

3.1.4 Molecular electronic spectra

Molecular electronic spectra of novel complexes were studied in a wavelength range between 200 and 800 nm at room temperature in DMF solution as blank (Fig. 2). The π-π* transition is referred to as the highest energy band, while the intermolecular charge transfer may be assigned to the shoulder band. In the UV–visible of the azomethine H2L ligand, bands at 360 and 386 nm are corresponding to n → π* transition that arise from the azomethine function group of the H2L (Supplementary Table S1). Bands at λ max = 418–451 nm are referred to LMCT transitions in the prepared imine complexes. LMCT transitions are the charge transition from the p‐orbitals of the H2L ligand to the d‐orbitals of VO(II), Zn(II) and ZrO(II) ions. In VOL electronic spectrum, a sharp band at 481 nm that does not appear in the H2L spectrum is more evident of the process of complexation. This band may be attributed to the d → d transition in its structure. The observed absorption spectra of the ZnL(H2O)2 and ZrOL complexes do not have any d–d transitions as seen in Fig. 2 since Zn(II) and ZrO(II) ions have d10 and d0 electronic structure, respectively.

Molecular electronic spectra of azomethine H2L ligand and its complexes in DMF (10−3 M) at 298 K.

3.1.5 Mass spectra

The structure of the H2L ligand and its ZrO(II), VO(II) and Zn(II) complexes were further proved by mass spectral data. The molecular ion peak of the ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 was recognized at m/z of 647, 610 and 645 respectively. The resultant molecular ions peaks are in good agreement with the proposed molecular weight from elemental and thermal analyses (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2021) (Supplementary Figures S9-S11).

3.1.6 Thermodynamic data analysis

TGA experiments were conducted to demonstrate the thermal stability of the complexes and to examine if the lattice or coordinated water molecules or both are existing in the structure of complexes (Chaurasia et al., 2019). The thermograms showed a complete decomposition around 750 °C at heating rate of 10 °C/minute under air atmosphere (Supplementary Figure S12). In Table 2, the percentage of the weight loss was detected and calculated with the temperature range of different decomposition stages. In the first step, both the lattice and the coordinated water molecules were lost while the organic moiety was eliminated in the second and third stages. In the last step of thermal decompositions, the metal oxides were formed as a final residue. ZrOL and VOL chelates have two lattice water molecules in their structures, while ZnL(H2O)2 have two lattice and two coordinated water molecules in its structure.

Compound

Dec. Temp. (°C)

Mass Loss (%)

Suggested segment

E# (kJmol−1)

A ×104(S−1)

Thermodynamic Parameters

Found

Calc.

Δ H # (kJ mol −1)

Δ S# (J mol−1K−1)

ΔG# (kJ mol−1)

35–130

5.60

5.54

2H2O ‘

170

0.29

168.9

−171.5

191.2

ZrOL

130–325

26.33

26.29

C6H3OBr

167.3

−179.5

225.6

325–490

25.85

25.80

C7H4Br

165.9

−182.6

255.4

490–715

23.34

23.41

C7H4N2Cl

164.1

−185.7

296.8

Residue

715

18.94

18.90

ZrO2

–

–

–

35–120

5.94

5.90

2H2O

180

0.34

199.4

−169.8

179.0

VOL

120–345

28.06

28.01

C6H3OBr

238.7

−178.5

177.1

345–500

27.56

27.61

C7H4Br

266.6

−181.6

175.8

500–720

24.86

24.89

C7H4N2Cl

307.1

−184.8

174.0

720

13.62

13.55

VO2

–

–

–

Residue

38–140

5.61

5.68

2H2O

58.5

−176.3

33.8

ZnL(H2O)2

140–250

5.61

5.70

2H2O

35

0.18

77.3

−181.2

32.0

250–360

28.66

28.59

C7H4OBr

98.4

−184.2

32.0

360–505

26.17

26.09

C7H4Br

125.2

−187.0

30.8

505–710

21.57

21.49

C6H3N2Cl

163.9

−189.9

29.1

Residue

710

12.38

12.45

ZnO

–

–

–

The kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of metal complexes have been determined by Coats-Redfern equation (Adly et al., 2013) and the data is given in Table 2. More data are available in previous study (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2018). In most thermal steps, the determined ΔS# values are negative which indicate that the prepared complexes were more activated ordered than the reactant and that the reaction rate is slow (Alturiqi et al., 2020). In the activated state, the reasons for the slowdown of the reaction might be the polarization of bonds and electronic transitions. The determined enthalpy values (ΔH#) are positive, referring that the processes of decomposition are endothermic (Alturiqi et al., 2020). The calculated values of ΔG# are high positive and showed that the decomposition steps are not spontaneous processes where the free energy of the initial compound is lower than that of the final residue (Alturiqi et al., 2020). The values of A are comparatively small, suggesting that the process is slowly pyrolysis. The values of E# are greater positive suggesting that the reaction have rotational, translational, and vibrational states and a variation in the mechanical potential energy for complexes.

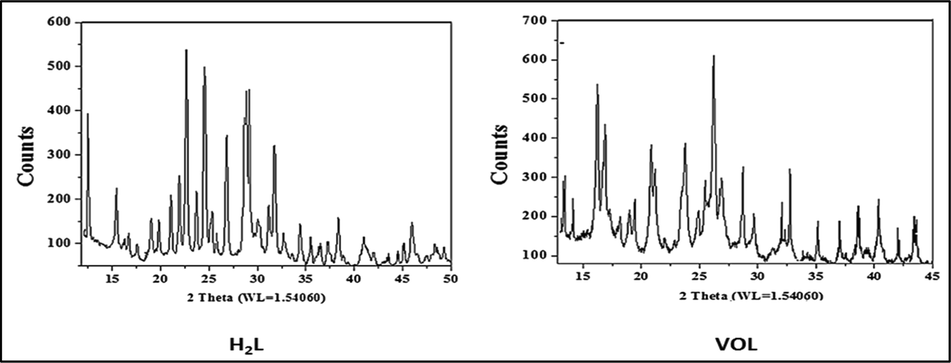

3.1.7 Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of the prepared compounds were undertaken over the 2

range 0–80° using wavelength 1.54060 Å. XRD result showed that the H2L ligand and its complexes have polycrystalline lattice where a ≠ b ≠ c and α = β = 90 ≠ γ as shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure S13 and S14 (Almáši et al., 2021). Importantly, the unit cell of H2L ligand has lattice constants a = 14.13600, b = 4.99500, c = 17.56300 Å and its space group is P1 2/c 1 (13). The unit cell of parameters of ZrOL complex are, a = 14.46100, b = 18.53500, c = 12.66300 Å and space group is C 1 2/c 1 (15). The obtained unit cell of the VOL complex has the lattice parameters, a = 28.09000, b = 7.99200, c = 20.16300 Å and its space group is C 1 2/c 1 (15). ZnL(H2O)2 complex has the lattice constants, a = 7.44250, b = 13.98900, c = 18.93600 Å and its space group is P 1 21/c 1 (14).

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of the H2L ligand and VOL complex.

3.1.8 Stability range of complexes

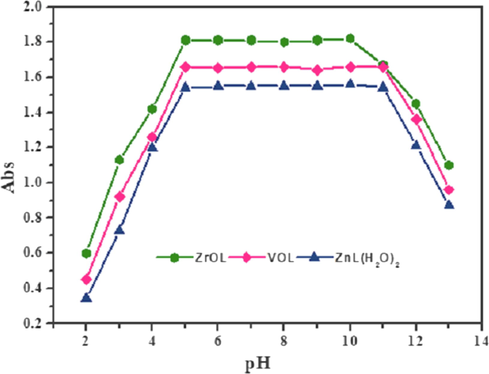

The pH graphic illustrates the high stability of the prepared complexes at multiple values of pH (Fig. 4). This activity means that the new complexes are more stable than ligand (H2L). Therefore, the appropriate pH range for the various implementations of the prepared metal chelates is from pH = 5 to 11.

The pH diagram of ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes at different pH values.

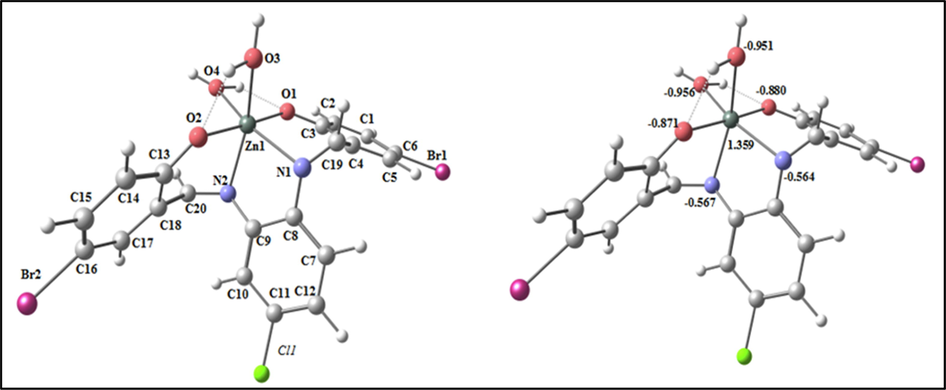

3.1.9 Geometry optimization with DFT method

3.1.9.1 Molecular calculation of the H2L

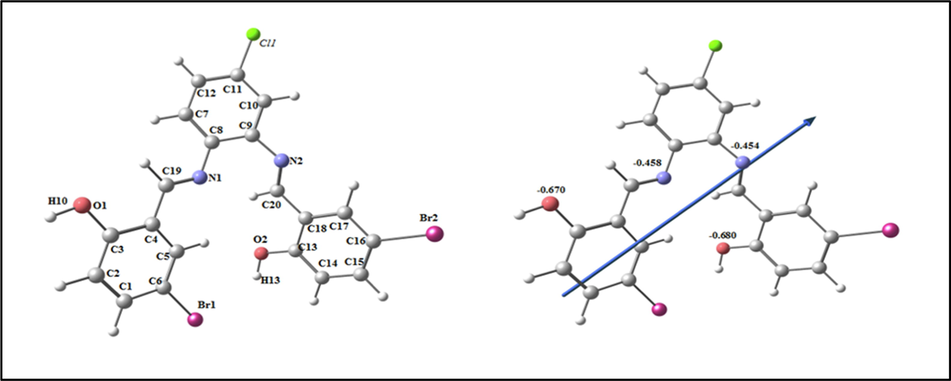

The optimized structure of the ligand H2L is seen as the lowest energy configuration in Fig. 5. The natural charges collected from Natural Bond Orbital Analysis (NBO) showed that O1(-0.670), O2(-0.680), N1 (-0.458)) and N2 (-0.480) are the most negative active locations for the H2L. So, the metal ions prefer tetra-dentate coordination to O1, O2, N1 and N2, designing a stable 5 and 6-membered chelate rings.

The optimized structure of ligand H2L, the vector of the dipole moment, and the natural charges on active centers.

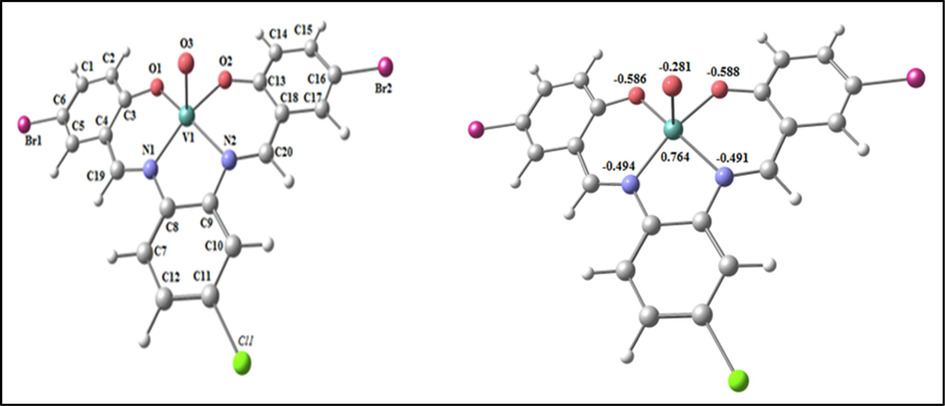

3.1.9.2 Molecular DFT calculation of VOL

The optimized structure of the complex VOL as the lowest energy configuration is displayed in Fig. 6. In a square pyramidal structure, the vanadium atom is five- member and Atoms N1, N2, O2 and O1 are diverted by 0.404° in one plane (Table S2). The distance between N1ــــــــN2, O1ــــــــO2 and N1ــــــــO1 are lowered from 2.985, 4.023 and 4.065 Å (in free H2L) to 2.753, 2.935 and 3.016 Å (in VOL), respectively, due to coordination of N1, N2, O1 and O2. From the NBO-analysis, the natural charges on the coordinated atoms in VOL are: V (+0.764), O3(-0.281), O1(-0.587), O2(-0.588), N1(-0.494) and N2(-0.491),

The optimized structure and the natural charges on active centers of VOL.

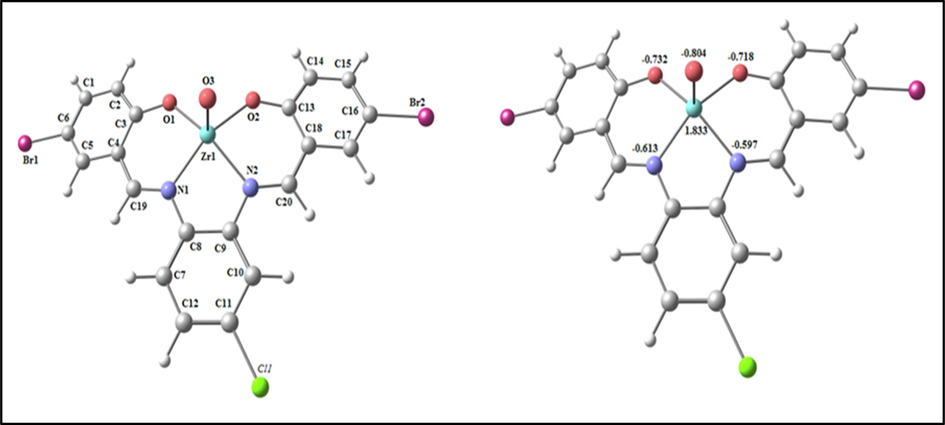

3.1.9.3 Molecular DFT calculation of ZrOL

The optimized structure of the ZrOL complex as the lowest energy configuration is seen in Fig. 7. In a square pyramidal structure, zirconium atom is five- member and the atoms N1, N2, O2 and O1 are deviated by −0.055° in one plane (Table S3). The distance between N1••• N2, O1••• O2 and N1••• O1 are lowered from 2.985, 4.023 and 4.065 Å (in free H2L) to 2.751, 2.937 and 3.026 Å (in ZrOL), respectively, due to coordination of N1, N2, O1 and O2. From the NBO-analysis, the natural charges on the coordinated atoms in ZrOL are: Zr (+1.833), O3(-0.804), N1(-0.613), N2(-0.597), O1(-0.732) and O2(-0.718).

The optimized structure and the natural charges on active centers of ZrOL.

3.1.9.4 Molecular DFT calculation of (ZnL(H2O)2)

The optimized structure of the complex (ZnL(H2O)2) as the lowest energy configuration is seen in Fig. 8. In a distorted octahedral structure, zinc atom is six-member and the atoms N1, O1, O4 and O2 are almost deviated by 3.285° in one plane (Table S4). The distance between N1••• N2, O1••• O2 and N1••• O1 are lowered from 2.985, 4.023 and 4.065 Å (in free H2L) to 2.931, 2.854 and 2.891 Å (in (ZnL(H2O)2)), respectively, due to coordination of N1, N2, O1 and O2. From the NBO-analysis, the natural charges on the coordinated atoms in (ZnL(H2O)2) are Zn(+1.359), N1(-0.564), N2(-0.567), O1(-0.880), O2(-0.871) ,O3(-0.951) and O4(-0.956).

The optimized structure and the natural charges on active centers of (ZnL(H2O2)).

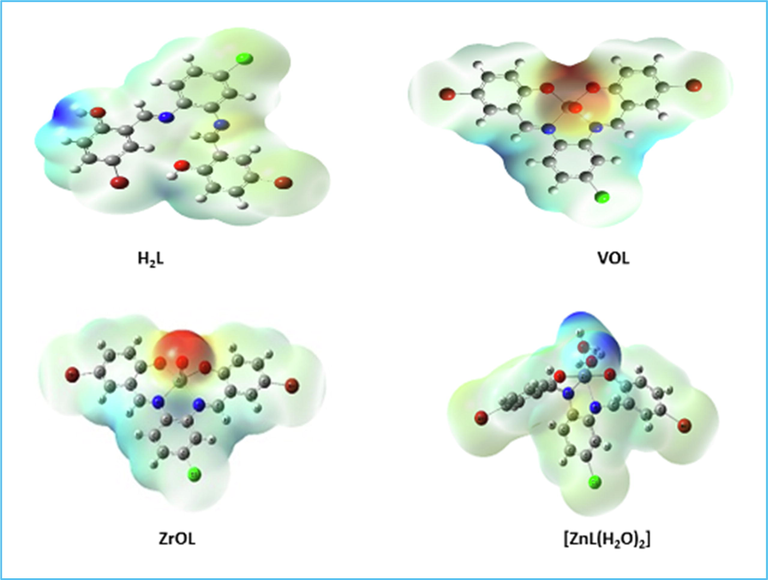

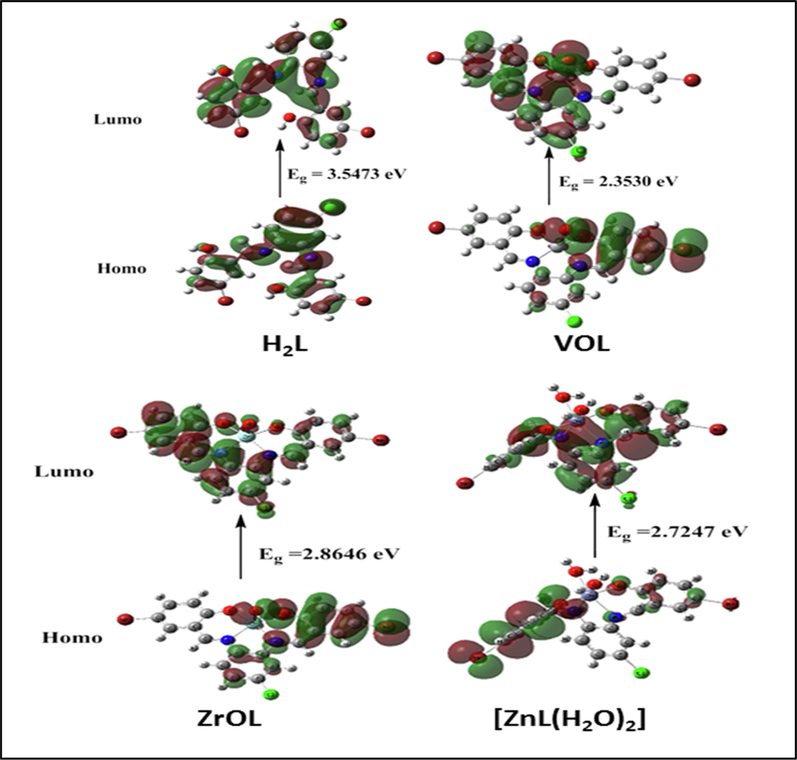

3.1.9.5 Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface

Fig. 9 indicates that the MEP surface is in the molecule to identify the positive (blue color) and negative (red color, loosely bound or excess electrons) charged electrostatic potential. It determined the overall measured energy, the highest occupied molecular orbital energies (HOMO), the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energies (LUMO) and the dipole moment for the titled compounds (Supplementary Table S5). The more negative values of the total energy of the complexes than that of the free ligand suggest that the new complexes are more stable than the free ligand and that, in the case of the new complexes, the energy gap (Eg) = ELUMO - EHOMO is smaller than that of their H2L ligand due to complexation process (Supplementary Table S5). Compared to that of their ligand, the reduction of energy gap in the prepared complexes describes the interactions of charge transfer upon forming complex (Fig. 10). Several descriptors of reactivity, such as electron affinity (A), ionization propensity (I), electronegativity (χ), Chem. potential (μ), softness (S), hardness (η) and electrophilicity index (ω), all obtained from the HOMO and LUMO energies, have been suggested to explain different aspects of Chem. reaction-related reactivity (Table 3).

Molecular electrostatic potential surface of H2L, VOL, ZrOL and ZnL(H2O)2.

HOMO and LUMO charge density maps of H2L, VOL, ZrOL and ZnL(H2O)2.

Ionization potential

I = -EHOMO

electron affinity A = -ELUMO

Electro-negativity

χ = (I + A)/2Chem. hardness η = (I -A)/2

Chem. softness S = 1/2η

Chem. potential μ = -χ

Electrophilicity ω = μ2/2η

H2L

5.9057

2.3584

4.13205

1.77365

0.2819

−4.13205

4.8132

VOL

5.8502

3.4972

4.6737

1.1765

0.4250

−4.6737

9.2832

ZrOL

6.0736

3.209

4.6413

1.4323

0.3491

−4.6413

7.5200

ZnL(H2O)2

5.651

2.9263

4.28865

1.36235

0.3670

−4.28865

6.7503

3.2 Biological applications

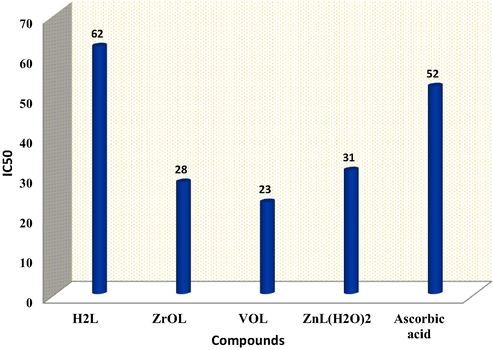

3.2.1 Antioxidant activity

Most experiments use the simple procedure of the DPPH assay to test the antioxidant efficacy of their targets (Mishra et al., 2012; Musa et al., 2013; Abu-Dief et al., 2020). It is possible to use the degree of color disappearance as an indicator of the intensity of the antioxidant activity of the studied compounds. The percentage of radical scavenging of the new compounds was determined and L-ascorbic acid was used as the reference standard at variable concentrations (10, 25, 50, 100 and 150 μM). Fig. 11 shows that, with the increased concentration of the prepared compounds, antioxidant activity increases, and the ligand has a moderate activity, whereas the new complexes are stronger than their H2L ligand activity. The resulting IC50 values showed a high potent activity of the VOL complex with an IC50 value 23.0 μM, while the ZnL(H2O)2 complex exhibited a lower antioxidant activity with higher value of IC50 (31.0 μM), as shown in Fig. 11. The order of the antioxidant activity of the prepared compounds are as follows: VOL > ZrOL > ZnL(H2O)2 > H2L. Structural parameters, such as the type and geometry of metal ions, influence on the anti-oxidative behavior of the compounds. The presence of the azomethine and phenolic group's Schiff base will increase the conjugated systems and thus increase the antioxidant potential of the metal chelates. In conclusion, antioxidant experiments have shown that novel compounds can help to develop the treatment of pathological diseases due to their oxidative stress, such as cancers, aging, and cardiovascular diseases.

Antioxidant activity of azomethine H2L ligand and its ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes determined by DPPH radical assay compared to ascorbic acid as a standard.

By comparing of the antioxidant activity results of our complexes VOL (23 μM) with the previously reported results of similar compounds, DAPHV (75 μM), we can conclude that our complex has better antioxidant activity compared to the reported one. (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2020a).

3.2.2 In vitro cytotoxicity screening

The in vitro cytotoxicity screening of the new complexes along with the respective H2L ligand was performed towards HCT-116, MCF-7 and HepG-2 adenocarcinoma cell lines and HEK-293 normal cells, in which vinblastine was set for the positive control using MTT assay (Andiappan et al., 2018; Ariyaeifar et al., 2018), as indicated in Table S6 and Fig. 12. The new compounds showed variable cytotoxic activity against tumor adenocarcinoma cell lines. The cytotoxicity screening results indicated that the new complexes are more potent than their H2L ligand and its complexes showed manifest cytotoxicity activity compared to the used reference drug. The minimum inhibition concentrations (IC50 µM) showed that the efficiency of the mentioned compounds is as follows: VOL > ZrOL > ZnL(H2O)2 > H2L ligand. More importantly, the prepared metal complexes are highly specific towards cancer cell lines only, as they exhibited mild toxicity against normal cell line (HEK-293), as illustrated in Fig. 12. The obtained results indicated that coordination of the H2L ligand with the studied metal ions enhanced anticancer potency. The increased potential anti-proliferative activity of metal complexes is attributed to the reason that the positive charge of the metal ions increases the acidity of the coordinated H2L ligand, which contains protons, allowing protons to form more potent hydrogen bonds with a negative charge in the DNA of carcinoma cells (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2019).

IC50 values of the azomethine H2L ligand and its ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes against HCT-116, MCF-7, HepG-2 and HEK-293 adenocarcinoma cell lines in which vinblastine was set for the positive control.

3.2.3 In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities

The new compounds were evaluated for Serratia marcescens, Micrococcus luteus, Escherichia coli, Geotrichum candidum, Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium oxysporum to determine their possible efficacy compared to the ofloxacin and fluconazole. (Saranya et al., 2020), Figs. 13, 14 and Table S7 and S8. A comparison of the antimicrobial activity of the new complexes, their H2L imine and reference drugs, found that the new complexes demonstrate higher potency compared to the H2L ligand. The increased activity is attributed to the coordination of metal ions with the free ligand. In addition, the new complexes have a medium potency compared to the used positive controls. Due to the partial sharing of the positive charge with the donor groups due to π-electron delocalization overall chelate ring, there is a reduction in the polarity of the metal significantly after complexation. Furthermore, reduced polarity enhanced the lipid soluble character of the chelates and strengthened the interaction between the complexes and the lipid, contributing to the eventual degradation of the cell's permeability barrier, which resulting in the obstruction of normal cell processes (Abdel Ghani and Mansour, 2011; Mohamed et al., 2019). The order of the antimicrobial activity of the new complexes is VOL > ZrOL > ZnL(H2O)2 complex. The antimicrobial capacity differential is due to the nature of the metal ions as well as the permeability of the microorganisms. The VOL complex is the most active with inhibition zone 53 ± 0.53 mm, which was very similar to that of a standard ofloxacin (55 ± 0.42 mm) for Micrococcus luteus bacteria. The new complexes show more relative reactivity against the micrococcus luteus gram-positive bacteria (23–53 mm) compared to the Serratia marcescens and Escherichia coli gram-negative bacteria (18–46 mm). The inhibition zone of the mentioned complexes is in the region (21–46 mm), (18–34 mm) and (21–37 mm) for Geotrichum candidum fungi, Aspergillus flavus fungi and Fusarium oxysporum fungi, respectively. By the serial dilution route, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was evaluated and recorded in Table S9 and Fig. 15. As seen in Table 4, the potential of the synthesized compounds was demonstrated by assessing the activity index.

Histogram showing the comparative antibacterial activities of the proposed compounds with Ofloxacin drug at a concentration of 30

M.

Histogram showing the comparative antifungal activities of the proposed compounds with Fluconazole drug at a concentration of 30

M.

Histogram showing the comparative of the MIC values (

M) between the new compounds, used drugs and negative control against the selected bacterial and fungal strains through a broth dilutions method.

Comp.

Activity index (%)

E. coli

M. luteus

S. marcescensas

G. candidum

A. flavus

F. oxysporum

H2L

37.5

36.4

38.3

33.3

36.1

38.5

ZrOL

87.5

89.0

91.5

89.6

86.1

89.7

VOL

95.0

96.4

97.8

95.8

94.4

94.9

ZnL(H2O)2

80.0

82.0

85.1

83.3

80.5

82.1

The antibacterial activity results, inhibition zone (mm), of the new complex ZnL(H2O)2 (18 mm) has been compared with some zinc complexes previously reported as complexes 5 and 8 (13 mm) in the literature (Shaghaghi et al., 2020). It is noticed that our complexes have better antibacterial activity than that of the complexes 5 and 8 against Escherichia coli.

3.2.4 DNA binding techniques

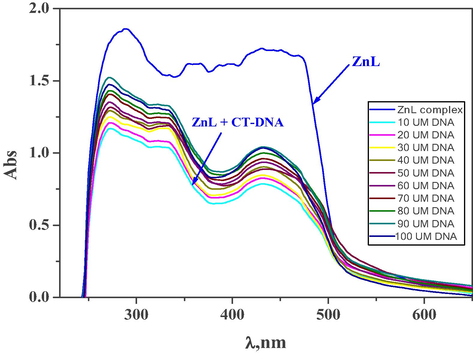

3.2.4.1 Spectrophotometric titration

Spectrophotometric titration is typically used to identify the DNA interaction with molecules (Zhang et al., 2021). Generally, changes in absorption and/or shift in characteristic peaks are due to the interaction of molecule with DNA. The strength of the interaction is determined by the degree of the shift. Electronic absorption of the new complexes in presence and absence of CT-DNA were scanned and displayed in Fig. 16 and Supplementary Figure S15. Absorption spectra of new complexes have a significant hypochromic effect mostly on addition of CT-DNA and a mild red shift has been identified, showing a powerful binding of CT-DNA with such complexes. Such spectral changes have been attributed to π-π stacking interactions between base pairs of DNA and the interacting ligand's π electron (Ramesh et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). The spectroscopic parameters and the determined intrinsic binding constants (Kb) of the interaction between the synthesized complexes with CT-DNA are listed in Table 5 and displayed in Supplementary Figure S16. In terms of the intrinsic binding constants (Kb), comparing the Kb values of our ZnL(H2O)2 (6.1

105 mol−1 dm−3) complex with ZnL (3.25

104 mol−1 dm−3) complex in the literature (Ramesh et al., 2020), showed that our complex has better binding affinity with DNA than that of the ZnL complex in the literature.

The change of electronic absorption spectra of ZnL(H2O)2 complex (10−3 M) upon addition of various amounts of CT-DNA (10–100

M).

Complex

λmax free (nm)

λmax bound (nm)

Δλ

Chromism (%)a

Type of Chromism

Kb

105 (mol−1 dm−3)

ΔG kJ mol−1

ZrOL

288

290

2

3.6

Hypo

6.6

–33.2

334

332

2

4.4

360

362

2

3.6

387

389

2

3.1

397

400

3

3.6

419

424

5

3.5

VOL

289

271

18

18.6

Hypo

7.8

–33.6

361

331

30

17.9

430

432

2

39.5

ZnL(H2O)2

288

292

4

12.1

Hypo

6.1

–33.0

356

351

5

29.7

387

385

2

34.4

431

429

2

38.7

481

537

56

70.3

566

580

14

79.2

3.2.4.2 Viscosity measurement

The binding features of complexes with CT-DNA was further confirmed by surface aggregation using viscosity due to that the spectrophotometric titration methods are not enough to confirm (Gandhimathi et al., 2017). This method of measurement is responsive to changes in the DNA length that might arise because of its binding to the complex (Rao et al., 2020). The substantial increase in the relative viscosity of the DNA with rising complex concentrations is shown in Fig. 17. This is like a positive standard. Thus, the average rise in DNA duration and viscosity could be owing to its intercalation binding with the new complexes.![The effect of increasing the amount of the prepared metal chelates on the relative viscosity of DNA at [DNA] = 260 μM, [complex] = 10–60 μM, and at 298 K.](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103737-fig18.png)

The effect of increasing the amount of the prepared metal chelates on the relative viscosity of DNA at [DNA] = 260 μM, [complex] = 10–60 μM, and at 298 K.

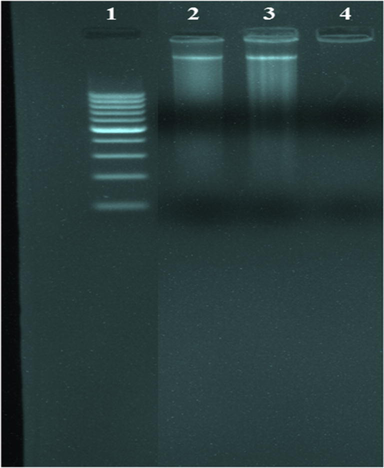

3.2.4.3 Gel electrophoresis technique

The technique of gel electrophoresis is used to research the influence of tested complexes on the degradation of genetic material. In this technique, the separation of complexes will be under the influence of an electric field based on their relative rate of movement through a gel (Prabhakara et al., 2015; Keypour et al., 2019). Fig. 18 shows that there was a small decrease in the strength of DNA treated with the complexes. Therefore, after such a genomic effect, the effect of these complexes on pathogen proliferation could be expected. The binding of a metal complex with DNA is beneficial in the design and improvement of pharmaceutical agents. The DNA binding techniques showed that through intercalation binding, the identified complexes can bind with DNA and demonstrates an obsequious and distinct DNA binding affinity.

Agarose gel electrophoresis photography of the prepared azomethine complexes. Lane 1: DNA Ladder, lane 2: VOL complex + DNA, lane 3: ZnL(H2O)2 complex + DNA, lane 4: ZrOL complex + DNA.

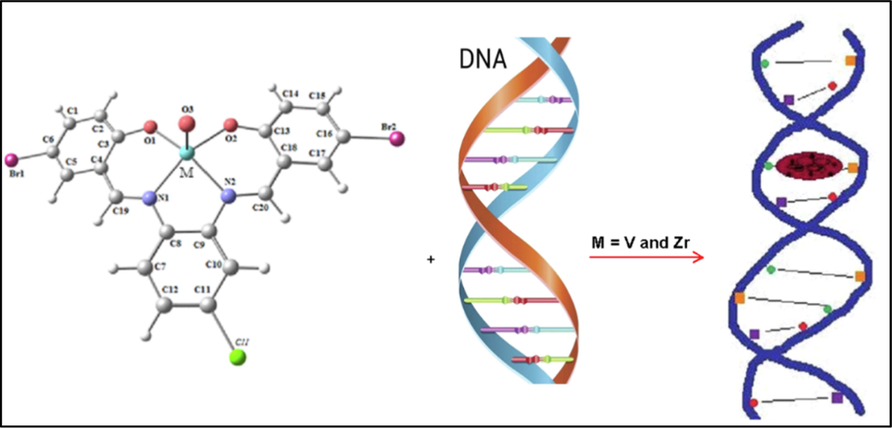

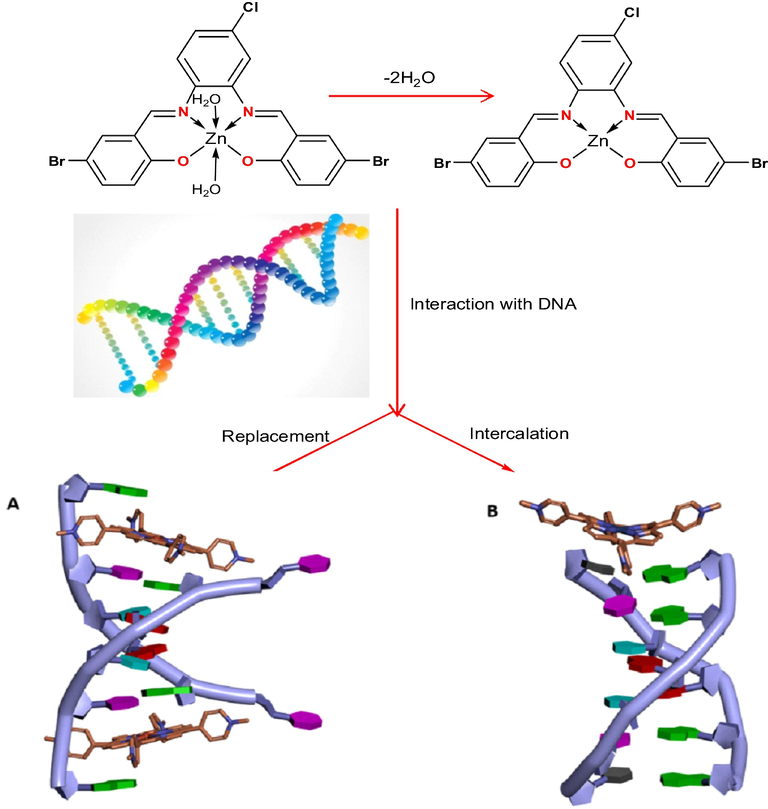

3.2.4.4 Proposed interaction mechanisms of the prepared imine complexes to DNA

The suggested interaction of VOL and ZrOL complexes with DNA is intercalative mode as shown in Scheme 2. In case of the ZnL(H2O)2 chelate, the two coordinated water molecules replaced by nitrogen bases of DNA. This leads to a flat part in the middle of this complex as shown in Scheme 3. So, the proposed interaction of VOL, ZrOL and ZnL(H2O)2 chelates with DNA is intercalation modes.

The suggested interaction of VOL and ZrOL complexes with CT-DNA.

The proposed interaction of ZnL(H2O)2 chelate with CT-DNA.

3.2.5 Molecular dynamics analysis

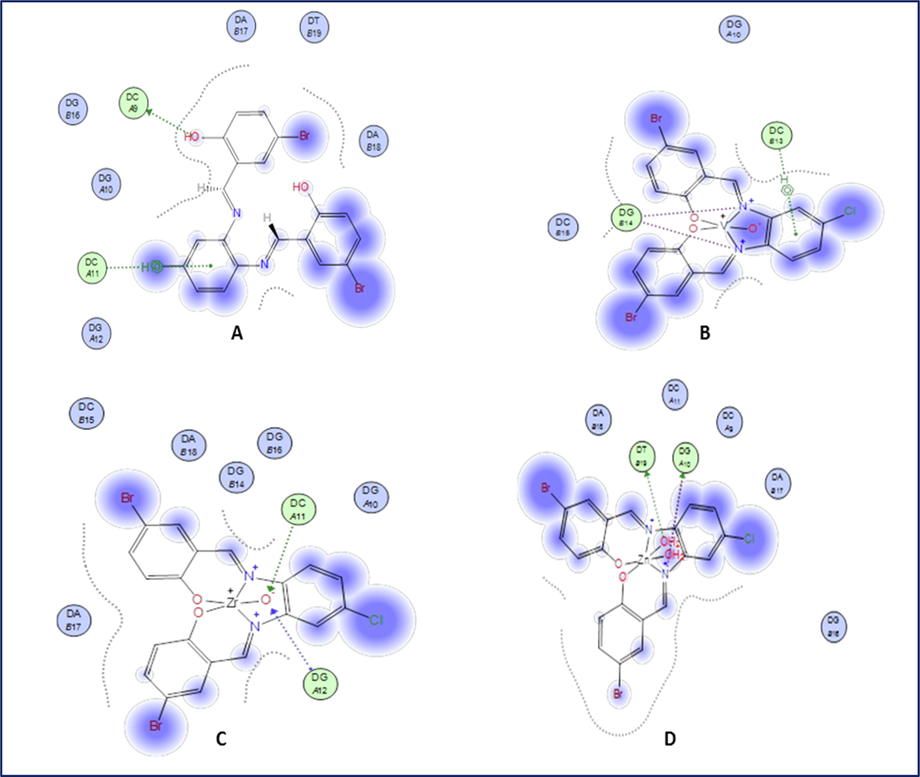

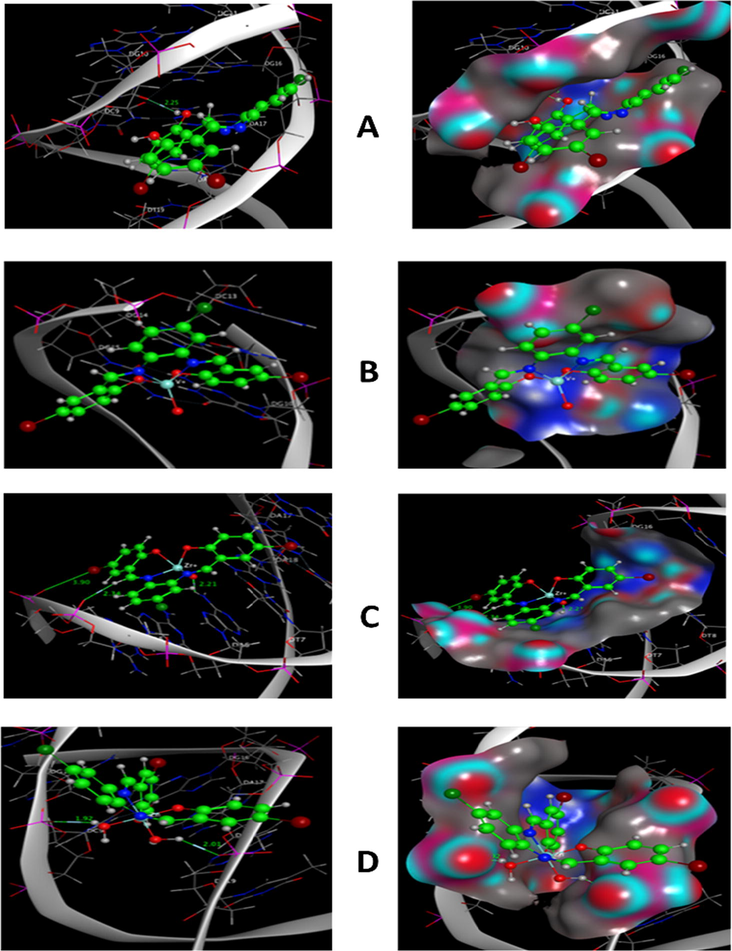

Molecular docking study is a necessary tool in drug design. It was utilized to evaluate the binding energy of the prepared complexes with DNA double helix. The structure of ligand and complexes was generated from the Gaussian 09 output program in PDB file format. The human DNA receptor (PDB ID:1BNA) structural properties have been obtained from the PDB database. Using MOA2014 tools, molecular modeling studies were done to classify the potential binding modes of the most active human DNA receptor site (PDB ID:1BNA) (Table 6 and Figs. 19 and 20). It was shown from the docking studies that H-acceptor is the main interaction force of the H2L ligand, while some binding interactions also occurred in complexes besides the main interaction of the ligand, such as H-donor and ionic. The order of the new compounds toward the binding with receptor is as follows: VOL, −6.2 > ZrOL, −5.9 > ZnL(H2O)2, −5.2 > H2L, −3.5 kcal/mol. The more negative energy is the more stable (stronger interaction). This showed that the mentioned complexes have better binding affinity than the free ligand. These results display good agreement with experimental observations. *The lengths of H-bonds are in brackets.

Receptor

Interaction

Distance(Å)*

E (kcal/mol)

H2L

O 26

O2 DC 9 (A)

H-donor

3.13 (2.25)

−2.6

6-ring

C4′ DC 11 (A)

pi-H

3.93

−0.9

VOL

N 22

OP2 DG 14 (B)

Ionic

3.22

−3.2

N 24

OP2 DG 14 (B)

Ionic

3.38

−2.4

6-ring

C3′ DC 13 (B)

pi-H

4.53

−0.6

ZrOL

C 20

OP2 DA 5 (A)

H-donor

3.39 (2.34)

−3.2

O 36

N6 DA 6 (A)

H-acceptor

3.11 (2.21)

−2.2

BR 38

OP2 DG 4 (A)

H-donor

3.90 (3.90)

−0.5

ZnL(H2O)2

O 36

OP1 DG 10 (A)

H-donor

2.75 (1.92)

−3.0

O 39

OP1 DT 19 (B)

H-donor

2.85 (2.01)

−1.7

N 25

OP1 DG 10 (A)

Ionic

3.99

−0.5

2D plot of the interaction between H2L (A), VOL (B), ZrOL (C) and ZnL(H2O)2 (D) with the active site of the receptor of human DNA (PDB ID:1BNA). Hydrophobic interactions with amino acid residues are shown with dotted curves.

Molecular docking simulation studies of the interaction between H2L (A), VOL (B), ZrOL (C) and ZnL(H2O)2 (D) with the active site of the receptor of human DNA (PDB ID:1BNA). The docked conformation of the compound is shown in ball and stick representation.

3.2.6 In silico ADMET analysis of the ligand and its complexes

ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination, Toxicity) prediction is used to predict toxicity and pharmacological properties of studied compounds using Swiss ADME server (Daina et al., 2017), Table 7. The obtained results showed that all computed properties are positives, indicating high probabilities, according to the results. Compounds with medium human intestinal absorption (HIA) and Caco2 permeation were forecasted to be non-AMES toxic and non-carcinogenic. The ligand and its compounds' total polar surface area (TPSA) characteristics indicate that they can absorb well in order to attach for a specific purpose when used as medicines.

ADME FACTOR a

H2L

VOL

ZrOL

ZnL(H2O)2

Physio - Chem. Properties

Molar Refractivity

118.29

122.84

122.84

128.25

TPSA

65.18 Å2

60.25 Å2

60.25 Å2

61.64 Å2

Lipophilicity

Log Po/w (iLOGP)

2.88

0.00

0.00

0.00

Log Po/w (XLOGP3)

5.82

5.48

5.48

5.09

Log Po/w (WLOGP)

6.78

6.17

6.17

6.16

Log Po/w (MLOGP)

4.49

3.20

3.20

2.46

Log Po/w (SILICOS-IT)

6.84

2.15

2.40

−0.21

Consensus Log Po/w

5.36

3.40

3.45

2.70

Water Solubility

Log S (ESOL)

−6.89

−7.31

−7.56

−7.26

Log S (Ali)

−6.96

−6.50

−6.50

−6.13

Log S (SILICOS-IT)

−8.60

−9.23

−9.31

−9.45

Class

Poorly soluble

Poorly soluble

Poorly soluble

Poorly soluble

Pharmacokinetics

GI absorption

Low

High

High

High

BBB permeant

No

No

No

No

P-gp substrate

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

CYP1A2 inhibitor

No

No

No

Yes

CYP2C19 inhibitor

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

CYP2C9 inhibitor

Yes

No

No

No

CYP2D6 inhibitor

No

No

No

No

CYP3A4 inhibitor

No

No

No

Yes

Log Kp (skin permeation)

−5.27 cm/s

−5.91 cm/s

−6.15 cm/s

−6.39 cm/s

Medicinal Chemistry

PAINS

0 alert

0 alert

0 alert

0 alert

Brenk

1 alert: imine_1

0 alert

0 alert

1 alert: heavy metal

Synthetic accessibility

3.00

4.18

4.04

4.34

4 Conclusions

A halogenated dibasic tetra-dentate chelating ligand and its ZrOL, VOL and ZnL(H2O)2 complexes were successfully synthesized, and their structure has been elucidated via spectroscopic tools. The complexes were formed in a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 (ligand‐to‐metal) ratio as confirmed by microanalysis. According to the analytical and spectral data, the obtained ZrOL, VOL complexes have distorted square pyramidal geometries, while ZnL(H2O)2 complex has a distorted octahedral geometry. The prepared complexes showed enhanced antioxidant activity compared to its H2L azomethine ligand. The antiproliferative activity of the studied H2L ligand and its complexes against Hep-G2, HCT-116 and MCF-7 cell lines lies in the following order: VOL > ZrOL > ZnL(H2O)2 > H2L. The In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activities showed that the prepared complexes have promising bioactivities against the tested microorganisms as compared to standard drugs. The DNA binding studies suggest that the mentioned complexes bind to DNA mainly via intercalation. For better understanding the nature of interaction with CT-DNA, a molecular docking study was also applied. The molecular docking studies showed that the new complexes have more negative energy than their ligand. This indicates that the new complexes strongly interact with DNA compared to their H2L ligand. Accordingly, we conclude that the finding of this research provides useful information to further create new metal complexes with high pharmacological activities.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/396), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the results of this study are available on fair request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Structural and in vitro cytotoxicity studies on 1H-benzimidazol-2-ylmethyl-N-phenyl amine and its Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes. Spectrochim. Acta. 2011;81:529-543.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H., Abu-Dief, Atlam, F.M., A.M., Abdel Mawgoud, A.A.H., Alothman, A.A., Alsalme A.M., Nafady A., 2020a. Chemical, physical, and biological properties of Pd(II), V(IV)O, and Ag(I) complexes of N3 tridentate pyridine-based Schiff base ligand. J. Coor. Chem. 73 3150-3173.

- Non-Linear Optical Property and Biological Assays of Therapeutic Potentials Under In Vitro Conditions of Pd(II), Ag(I) and Cu(II) Complexes of 5-Diethyl Amino-2-({2-[(2-Hydroxy-Benzylidene)-Amino]-Phenylimino}-Methyl)-Phenol. Molecules. 2020;25:5089.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, theoretical investigations, biocidal screening, DNA binding, in vitro cytotoxicity and molecular docking of novel Cu (II), Pd (II) and Ag (I) complexes of chlorobenzylidene Schiff base: Promising antibiotic and anticancer agents. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2018;32:e4527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, L.H., Basha, M.T., Al-Farhan, B.S., Shehata, M.R., Abdalla, E.M., 2021. Synthesis, characterization, potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, DNA binding, and molecular docking activities and DFT on novel Co(II), Ni(II), VO(II), Cr(III), and La(III) Schiff base complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. e6484.

- Novel Cr (III), Fe (III) and Ru (III) Vanillin Based MetalloPharmaceuticals for Cancer and Inflammation Treatment: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Appl. Organomet al. Chem.. 2019;33:e5177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, DFT calculations and biological studies of Mn(II), Fe(II), Co(II) and Cd(II) complexes based on a tetradentate ONNO donor Schiff base ligand. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1134:851-862.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cobalt (II), zirconium(IV), calcium(II) complexes with dipicolinic acid and imidazole derivatives: X-ray studies, thermal analyses, evaluation as in vitro antibacterial and cytotoxic agents. Inorg. Chimica Acta. 2018;480:70-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- New transition metal complexes of 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde benzoylhydrazone Schiff base (H2dhbh): Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, DNA binding/cleavage and antioxidant activity. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1158:39-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- A robust in vitro Anticancer, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Agents Based on New Metal-Azomethine Chelates Incorporating Ag(I), Pd (II) and VO (II) Cations: Probing the Aspects of DNA Interaction. Appl. Organometal. Chem.. 2020;34:e5373.

- [Google Scholar]

- Targeting ctDNA binding and elaborated in-vitro assessments concerning novel Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, characterization, DFT and detailed in-silico confirmation. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;322:114977.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tailoring, structural inspection of novel oxy and non-oxy metal-imine chelates for DNA interaction, pharmaceutical and molecular docking studies. Polyhedron. 2021;201:115167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological potential of oxo-vanadium salicylediene aminoacid complexes as cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antioxidant and DNA interaction. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2018;184:34-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectral characterization, molecular modeling and antimicrobial activity of new potentially N2O2 Schiff base complexes. J. Mol. Struct.. 2013;1054:239-250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and spectral properties of novel azo-azomethinetetracarboxylic Schiff base ligand and its Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Pd(II) complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2021;515:120064.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, Characterization, Spectroscopy and Bactericidal Properties of Polydentate Schiff Bases Derived from Salicylaldehyde and Anilines and their Complexes. J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2016;8:290-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic Oxidation of Benzyl Alcohol Using Nanosized Cu/Ni Schiff-Base Complexes and Their Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Catal.. 2018;8:452.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural identification, DNA interaction and biological studies of divalent metal(II) chelates of 1,2- ethenediamine Schiff base ligand. J. Mol. Struc.. 2020;1219:128542.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro cytotoxicity activity of novel Schiff base ligand–lanthanide complexes. Sci. Rep.. 2018;8:3054.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chiral halogenated Schiff base compounds: green synthesis, anticancer activity and DNA-binding study. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1161:497-511.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chiral halogenated Schiff base compounds: green synthesis, anticancer activity and DNA-binding study. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1161:497-511.

- [Google Scholar]

- New Zn (II) and Cd (II) complexes of 2,4-dihydroxy-5-[(5-mercapto-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-yl)diazenyl] benzaldehyde: Synthesis, structural characterization, molecular modeling and docking studies, DNA binding and biological activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2020;34:e5635.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, crystal structure and characterization of manganese (III) complex containing a tetradentate Schiff base. J. Coord. Chem.. 2013;66:4292-4303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological evaluation of some thiazolyl and thiadiazolyl derivatives of 1H pyrazole as anti-inflammatory antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2008;43:456-463.

- [Google Scholar]

- Syntheses, characterization, superoxide dismutase, antimicrobial, crystal structure and molecular studies of copper (II) and nickel (II) complexes with 2-((E)-(2, 4-dibromophenylimino) methyl)-4-bromophenol as Schiff base ligand. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1149:846-861.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of mononuclear Co (II), Ni (II), Cu (II) and Pd (II) complexes with new N2O2 Schiff base ligands. Chem. Pharm. Bull.. 2011;59:166-171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural characterization, and biological activities of metal(II) complexes with Schiff bases derived from 5-bromosalicylaldehyde: Ru(II) complexes transfer hydrogenation. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2019;23:205-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectral characterization, and DNA binding studies of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of Schiff base 2-((1H–1,2,4-triazol-3-ylimino)methyl)-5-methoxyphenol. J. Mol. Struct.. 2019;1179:431-442.

- [Google Scholar]

- New cytotoxic zinc(II) and copper(II) complexes of Schiff base ligands derived from homopiperonylamine and halogenated salicylaldehyde. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2021;516:120171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metal based neurodegenerative diseases–from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2008;252:1189-1199.

- [Google Scholar]

- SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics drug-likeness and Med. Chem. friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectral characterization, solution equilibria, in vitro antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of Cu(II), Ni(II), Mn(II), Co(II) and Zn(II) complexes with Schiff base derived from 5-bromosalicylaldehyde and 2-aminomethylthiophene. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 2011;79:1803-1814.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M,. 2020. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. (https://gco.iarc.fr/today, accessed February 2021).

- Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G.A., Nakatsuji, H., Caricato, M., Li, X., Hratchian, H.P., Izmaylov, A.F., Bloino, J., Zheng, G., Sonnenberg, J.L., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Montgomery, J.A., Peralta, J.E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M., Heyd, J.J., Brothers, E., Kudin, K.N., Staroverov, V.N., Keith, T., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A., Burant, J.C., Iyengar, S.S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Rega, N., Millam, J.M., Klene, M., Knox J.E.,, Cross, J.B., Bakken, V., Adamo, C., Jaramillo, J., Gomperts, R., Stratmann, R.E., Yazyev, O., Austin, A.J., Cammi, R., Pomelli, C., Ochterski, J.W., Martin, R.L., Morokuma, K., Zakrzewski, V.G., Voth, G.A., Salvador, P., Dannenberg, J.J., Dapprich, S., Daniels, A.D., Farkas, O., Foresman, J.B., Ortiz, J.V., Cioslowski, J., Fox, D.J., 2010. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT.

- Crystal structure, theoretical and experimental electronic structure and DNA/BSA protein interactions of nickel(II) N2O2 tetradentate Schiff base complexes. Polyhedron. 2017;138:88-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cooperative multimetallic catalysis using metallosalens. Chem. Commun.. 2010;46:2713-2723.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes of halogenated bidentate N, O-donor Schiff base ligands: Synthesis, characterization, crystal structures, DNA binding, molecular docking, DFT and TD-DFT computational studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2021;514:120004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-recognition of the racemic ligand in the formation of homochiral dinuclear V (V) complex: In vitro anticancer activity, DNA and HSA interaction. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;35:230-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure, DNA- and HSA-binding studies of a dinuclear Schiff base Zn(II) complex derived from 2-hydroxynaphtaldehyde and 2-picolylamine. J. Mol. Struct.. 2015;1096:110-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Robert William Gable, DNA binding studies and antibacterial properties of a new Schiff base ligand containing homopiperazine and products of its reaction with Zn(II), Cu(II) and Co(II) metal ions: X-ray crystal structure of Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes. Polyhedron. 2019;170:584-592.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the Halogen Substitution Pattern on the Biological Activity of Organoruthenium 8-Hydroxyquinoline Anticancer Agents. Organometallics. 2015;34:5658-5668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combining anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activities in ternary metal-NSAID complexes of a polypyridylamine ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2019;486:663-668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural and antimicrobial studies of half-sandwich ruthenium, rhodium and iridium complexes containing nitrogen donor Schiff-base ligands. J. Mol. Struct.. 2019;1191:314-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent development of transition metal complexes with in vivo antitumor activity. J. Inorg. Biochem.. 2017;177:276-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, crystal structure, DNA interaction and antioxidant activities of two novel water-soluble Cu (II) complexes derivated from 2-oxo-quinoline-3-carbaldehyde Schiff-bases. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2009;44:4477e4484.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of antiradical properties of antioxidants using DPPH assay: a critical review and results. Food Chem.. 2012;130:1036-1043.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, theoretical study and biological activity of Schiff base nanomaterial analogues. J. Mol. Struc.. 2019;1181:645-659.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of a new zinc(II) complex with tetradentate azo-thioether ligand: X-ray structure, DNA binding study and DFT calculation. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1146:146-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel high throughput method based on the DPPH dry reagent array for determination of antioxidant activity. Food Chem.. 2013;141:4102-4106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectral characterization, cyclic voltammetry, morphology, biological activities and DNA cleaving studies of amino acid Schiff base metal (II) complexes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2008;71:1599-1609.

- [Google Scholar]

- The side effects of platinum-based chemotherapy drugs: a review for chemists. Dalton Trans.. 2018;47:6645-6653.

- [Google Scholar]

- UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem.. 2004;25:1605-1612.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectral, thermal, fluorescence, antimicrobial, anthelmintic and DNA cleavage studies of mononuclear metal chelates of bi-dentate 2H-chromene-2-one Schiff base. J. Photochem. Photobio.. 2015;148:322-332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterizations, biological activities and docking studies of novel dihydroxy derivatives of natural phenolic monoterpenoids containing azomethine linkage. Res. Chem. Intermed.. 2017;43:5377-5393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative anti-proliferative studies of natural phenolic monoterpenoids on human malignant tumour cells. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2016;5:2167-10412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectroscopic, DFT studies and biological activity of some ruthenium carbonyl derivatives of bis-(salicylaldehyde) phenylenediimine Schiff base ligand. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1161:100-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rambabu, A., Kumar, M.P., Ganji, N., Daravath, S., Shivaraj, 2020. DNA binding and cleavage, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial studies of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes of 1-((E)-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylimino)methyl)naphthalen-2-ol Schiff base. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 38, 307–316.

- Ramesh, G., Daravath, S., Swathi, M., Sumalatha, V., Shankar, D.S., Shivaraj, 2020. Investigation on Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes derived from quadridentate salen-type Schiff base: Structural characterization, DNA interactions, antioxidant proficiency and biological evaluation. Chem. Data Collections 000, 100434.

- Rao, N.N., kishan, E., Gopichand, K., Nagaraju, R., Ganai, A.M., Rao, P.V., 2020. Design, synthesis, spectral characterization, DNA binding, photo cleavage and antibacterial studies of transition metal complexes of benzothiazole Schiff base. Chem. Data Collections 27, 100368.

- Distorted square-antiprism geometry of new zirconium (IV) Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, spectral characterization, crystal structure and investigation of biological properties. J. Mol. Struct.. 2017;1149:576-584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, antioxidant, antimicrobial, DNA binding and molecular docking studies of morpholine based Schiff base ligand and its metal (II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. Comm.. 2021;124:108396.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gold(III) complex from pyrimidine and morpholine analogue Schiff base ligand: Synthesis, characterization, DFT, TDDFT, catalytic, anticancer, molecular modeling with DNA and BSA and DNA binding studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;294:111655.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tetradentate Schif Base Complexes of Transition Metals for Antimicrobial Activity. Arab. J. Sci. Engi.. 2020;45:4683-4695.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and cellular ultrastructural effects of heteroleptic oxidovanadium(IV) complexes of salicylaldimines and polypyridyl ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem.. 2017;166:162-172.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optical, electrochemical, thermal, biological and theoretical studies of some chloro and bromo based metal-salophen complexes. J. Mol. Struc.. 2020;1200:127107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of Benzothiazole Schiff ’s bases and screening for the anti-oxidant activity. World J. Pharm. Res.. 2017;6:610-616.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel water soluble Schiff base metal complexes: Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial-, DNA cleavage, and anticancer activity. J. Mol. Struct.. 2020;1221:128770.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tailored synthesis of unsymmetrical tetradentate ONNO Schiff base complexes of Fe(IIl), Co(II) and Ni(II): spectroscopic characterization, DFT optimization, oxygen-binding study, antibacterial and anticorrosion activity. J. Mol. Struct.. 2020;1202:127362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemicals: Current strategy to sensitize cancer cells to cisplatin. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2019;110:518-527.

- [Google Scholar]

- A structure-activity relationship study of Forkhead Domain Inhibitors (FDI): The importance of halogen binding interactions. Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;93:103269.

- [Google Scholar]

- New Ru(II) half sandwich complexes bearing the N, N/ bidentate 9-ethyl-N-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)9H-carbazole-3-amine ligand: Effects of halogen (Cl, Br and I) leaving groups versus in vitro activity on HepG2 cancer cells, cell cycle, fluorescence study, cellular accumulation and DFT study. Polyhedron. 2018;152:37-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Turan, B., S¸ endil, K., S¸ engül, E., Gültekin, M.S., Taslimi, P., Gulçin, I., Supuran, C.T., 2016. The synthesis of some β-lactams and investigation of their metalchelating activity, carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase inhibition profiles. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31, 79–88.

- Synthesis, Characterization, Thermal and Catalytic Studies of Oxovanadium(IV) Complexes with Tetradentate ONNO Donor Ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., India. Sect. A Phys. Sci.. 2017;87:11-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yeyea, E.O., Kanwala, Khana, K.M., Chigurupatid, S., Wadoode, A., Rehmane, A.U., Perveenf, S., Maharajang, M.K., Shamima, S., Hameeda, S., Aboabab, S.A., Taha, M., 2020. Syntheses, in vitro α-amylase and α-glucosidase dual inhibitory activities of 4-amino-1,2,4-triazole derivatives their molecular docking and kinetic studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 28, 115467.

- Design and biological evaluations of mono- and di-nuclear copper(II) complexes: Nuclease activity, cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Polyhedron. 2021;193(114880):29.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103737.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1