Translate this page into:

Synthesis, and biological screening of chloropyrazine conjugated benzothiazepine derivatives as potential antimicrobial, antitubercular and cytotoxic agents

⁎Corresponding authors. bashafoye@gmail.com (Afzal B. Shaik), r.bhandareh@ajman.ac.ae (Richie R. Bhandare), m.rahman@uel.ac.uk (M. Mukhlesur Rahman)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

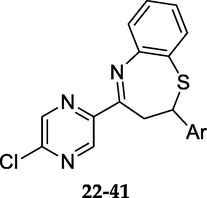

A series of twenty new chloropyrazine conjugated benzothiazepines (22–41) have been synthesized with 58%–95% yields. The compounds were characterized by using different spectroscopic techniques including FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The synthesized compounds (22–41) and their precursor chalcones (2–21) were evaluated for antitubercular and cytotoxic activities. Additionally, compounds 22–41 were also tested for antimicrobial activity. Among the chalcone series (2–21), compounds 7 and 14 showed significant antitubercular activities (MICs 25.51 and 23.89 µM, respectively), whereas among benzothiazepines (22–41), compounds 27 and 34 displayed significant antimicrobial (MICs 38.02 µM, 19.01 µM) and antitubercular (MIC 18.10 µM) activities. Compounds 7 and 41 displayed cytotoxic activities with IC50 of 46.03 ± 1 and 35.10 ± 2 µM respectively. All the compounds were evaluated for cytotoxic activity on normal human liver cell lines (L02) and found to be relatively less selective towards this cell line. The most active compounds identified through this study could be considered as potential leads for the development of drugs with possible antimicrobial, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities.

Keywords

Chloropyrazine

Benzothiazepines

Antitubercular

Antimicrobial

Cytotoxic

1 Introduction

Heterocyclic compounds play a vital role in the design and development of drugs against different diseases. More than seventy percent of drugs used in therapy contain one or more heterocyclic rings. Out of the 24 small drug molecules approved in 2020 by Food and Drug Administration (FDA), USA, 22 drugs contain heterocyclic rings. Similarly, of the 10 top drugs prescribed in USA, six drugs contain heterocyclic rings. This scenario is due to the property of the heterocyclic rings to serve as useful templates to modulate physicochemical properties of the drug molecules including the hydrogen bond capacity, polarity, and lipophilicity. Presence of hetero atoms or heterocyclic nucleus within the molecules may further improve pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and toxicological profiles of the drug candidates and finally drug molecules (Gomtsyan, 2012). Some of the heterocyclic rings are considered as privileged because of their significant drug-like properties. Medicinal chemists usually club or conjugate two or more such privileged heterocycles to create biologically useful molecules as a part of drug discovery programs. In the recent past, the design and synthesis of heterocyclic hybrids have received greater attention due to their ease of synthesis and improved biological properties. The structures that evolve from such conjugation are usually rigid frameworks that can show the appended rings in a well‐defined fashion that is necessary for molecular recognition of the biological target. Usually, the variable nature of these functionalities defines the selectivity on a privileged core for a particular target.

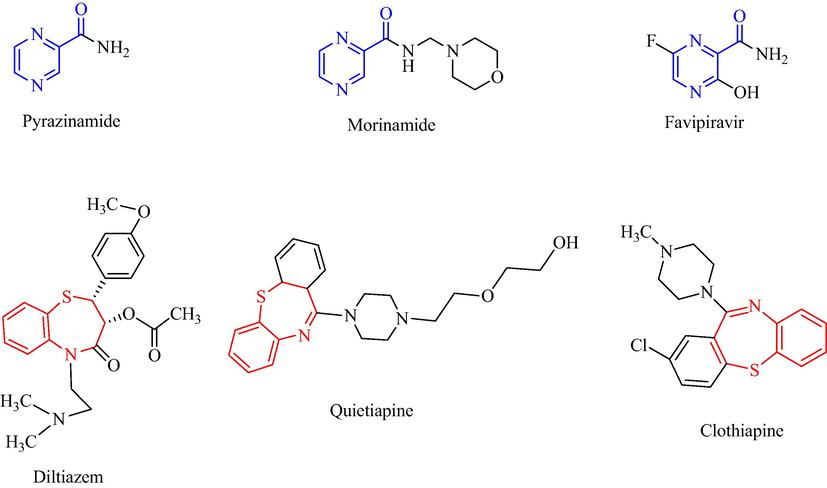

Pyrazine and 1,5-benzothiazepine rings are two privileged aromatic heterocycles of interest to organic and medicinal chemists because of their ease of synthesis and biological activities. Both these scaffolds are prominent in a variety of drugs used in the treatment of different complications. For example, pyrazine ring is found in drugs like pyrazinamide (PZA) and morinamide (antitubercular), favipiravir (anti-corona viral), glipizide (antidiabetic), amiloride and benzamil (diuretic), acipimox (antihyperlipidemic), and bortezomib (multiple myeloma). 1,5-benzothiazepine scaffold is present in calcium channel blockers for cardiovascular problems- Diltiazem and Clentiazem (Nagao et al., 1972, Chaffman and Brogden, 1985), atypical antipsychotic agents- Quetiapine and Clotiapine, and the antidepressant drug- Thiazesim (Kawakita et al., 1991, Geyer et al., 1970, Hopenwasser et al., 2004) (Fig. 1).

Representative structures of clinically used pyrazine and benzothiazepine ring containing drugs.

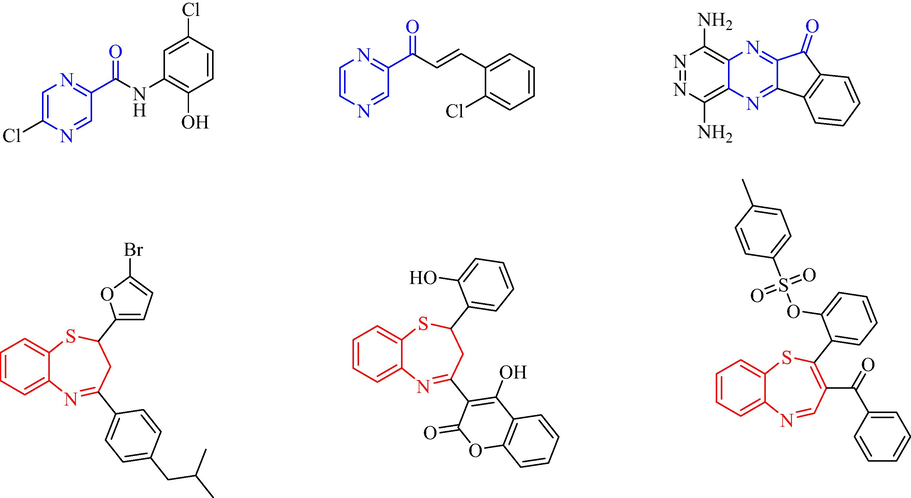

Pyrazine derivatives were reported to possess excellent antitubercular (Ambrożkiewicz et al., 2020, Bouz et al., 2020, Zitko et al., 2018, Miniyar et al., 2017, Zitko et al., 2016, Servusova-Vanaskova et al., 2015, Servusová et al., 2013, Zitko et al., 2013, Mangrolia and Osborne, 2020), anticancer (De Wang et al., 2020, Tantawy et al., 2020, Etaiw et al., 2020, Seo et al., 2020, Mamedova et al., 2019, Patil et al., 2019, Bhaskar et al., 2020), antimicrobial (Singh et al., 2020, Kucerova-Chlupacova et al., 2016, Kucerova-Chlupacova et al., 2015, Stepanić et al., 2019, Kucerova-Chlupacova et al., 2018), antioxidant (Cavalier et al., 2001, Zaki et al., 2018, Abu-Hashem and El-Shazly, 2018), analgesic and anti-inflammatory (Shankar et al., 2017, Aneesa et al., 2015, Bills et al., 1939, Bariwal et al., 2008), and anti-pellagra activities (El-Bayouki, 2011). Many authors have reviewed the synthesis, characterization, and applications of benzothiazepines (Deshmukh et al., 2016, Saha et al., 2015, El-Bayouki, 2013, Sekhar, 2014, Shaik et al., 2020a,b, Wu et al., 2017). This ring derivatives have shown promising anticancer (Gudisela et al., 2017, Ameta et al., 2012, Arya and Dandia, 2008, Ansari et al., 2008, Sharma et al., 1997, Upadhyay et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2020), antitubercular (Kendre et al., 2019), antibacterial and antifungal (Yan et al., 2019, Tongxiu et al., 2018, Pant et al., 2018, Mor et al., 2017, Patel et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017, El-Bayouki, 2013), antiviral (Di Santo and Costi, 2005, Kishor et al., 2017, Lokesh et al., 2017) activities. Representative structures of important pyrazine and benzothiazepine derivatives with potential antimycobacterial, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities are displayed below (Fig. 2).

Structures of selected pyrazine and 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives with potent antimicrobial, antitubercular and anticancer activities.

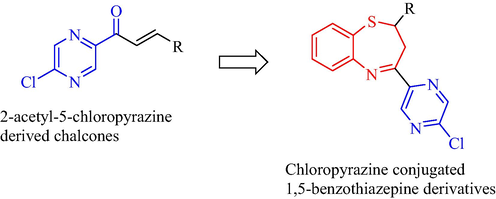

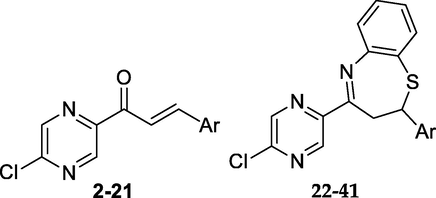

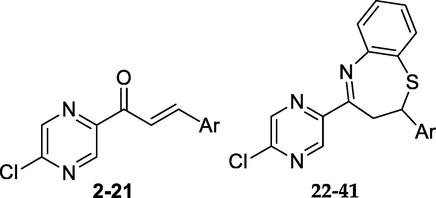

In continuation for our interest in the synthesis and screening of heteroaryl chalcones (Shaik et al., 2020a,b, Lokesh et al., 2019a,b) and conjugated heterocycles (Palleapati et al., 2019, Lokesh et al., 2019a,b, Yazdan et al., 2015) as well as the potential bioactivities of conjugated heterocyclic derivatives, we prepared and screened novel chloropyrazine conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives. Both pyrazine and 1,5-benzothiazepine rings exhibited promising antimicrobial, antitubercular and cytotoxic activities as discussed above. Hence, the molecules synthesized for our study were expected to possess collective effect on the proposed activities. We have previously described the antibacterial & antifungal activities of chloropyrazine chalcones (2–21) (Vegesna et al., 2017). Herein, we reported the synthesis of twenty new chloropyrazine conjugated benzothiazepines (22–41) as well as the antitubercular and cytotoxic activities of precursor chalcones (2–21), antimicrobial, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities of chloropyrazine conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives (22–41). The general structures of the chloropyrazine chalcones and chloropyrazine conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepines are portrayed in Fig. 3.

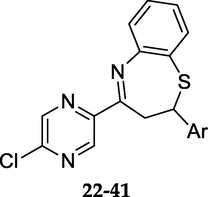

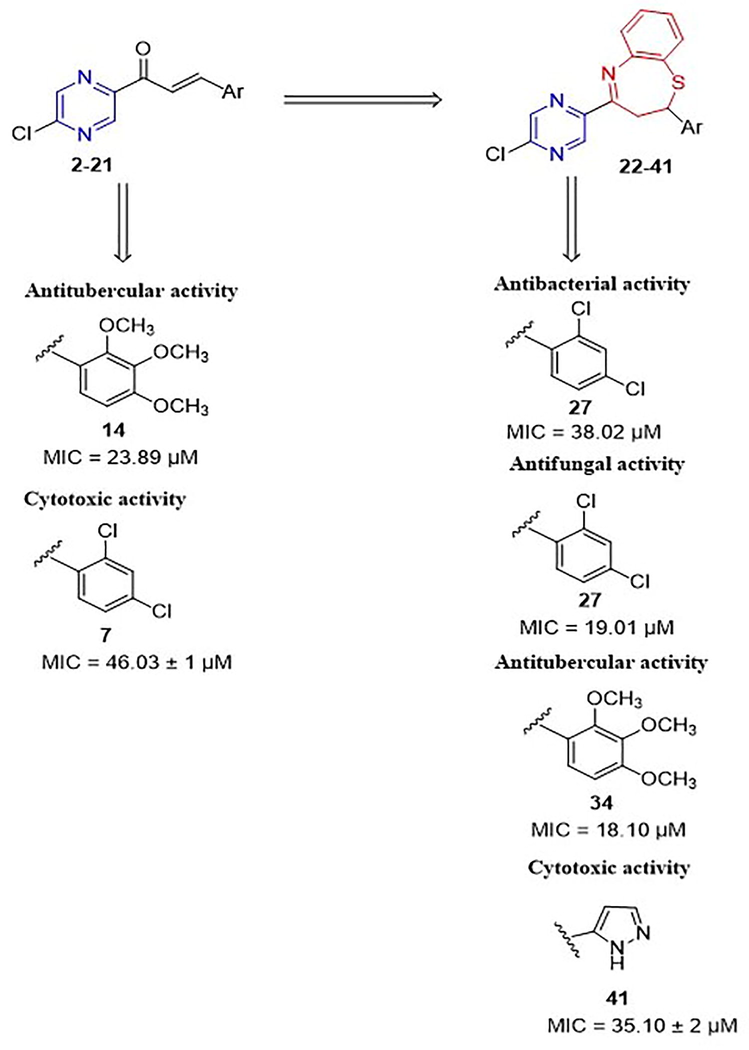

General structures of 2-acetyl-5-chloropyrazine chalcones and chloropyrazine conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 General

All solvents and reagents were obtained from S.D. Fine. Ltd. Mumbai, India and Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co (USA) and used without further purification. Pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 plates were used for thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and the spots on the TLC plates were visualized by UV lamp (254 nm). The benzothiazepines (22–41) were purified by recrystallization using ethanol. Melting points were determined on Boetius melting point apparatus in open capillary tubes and were uncorrected. FT-IR spectra were recorded on Bruker Vertex 80v spectrometer using potassium bromide discs and the absorption band values are given in cm−1. Proton and carbon magnetic resonance (1H NMR and 13C NMR) were recorded on Bruker AMX 400 NMR spectrophotometer using Tetramethyl silane (TMS) as internal standard and the chemical shift values are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to TMS. Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on Agilent 6100 QQQ ESI mass spectrophotometer by electron spray ionization technique.

2.2 Experimental

2.2.1 General procedure for the synthesis of chalcones (2–21)

To a mixture of 2-acetyl-5-chloropyrazine (0.001 M) and the appropriate aryl or heteroaryl aldehyde (0.001 M) was stirred in ethanol (7.5 mL) and to it aqueous solution of NaOH (40%, 7.5 mL) was added. The mixture was kept for 24 h and it was acidified with 1:1 mixture of hydrochloric acid and water, then it was filtered under vacuum and the product was washed with water (Vegesna et al., 2017).

2.2.2 General procedure for the synthesis of chloropyrazine conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepines (22–41)

To a mixture of 1 mmol of chalcones (2–21) and 1.5 mmol of 2-Aminothiophenol in dry methanol (50 mL), a catalytic amount of piperidine was added. The mixture was refluxed for 8 h. After cooling, the solid product separated was collected and washed with diethyl ether (2 × 50 mL) and cold methanol (2 × 50 mL). The crude solid was recrystallized from ethanol (Shaik et al., 2020a,b).

2.2.2.1 2,3-Dihydro-2-phenyl-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (22)

FT-IR (KBr): 1584 (C⚌N), 1510 (C⚌C), 1395 (C—N), 663 (C—S), 879 (C—Cl), 3032 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.11 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.52 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.21 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.19–8.22 (11H, Ar—H); 13H NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 50.15 (C-2), 40.24 (C-3), 164.66 (C-4), 122.54, 126.44, 127.51, 127.81, 128.80, 133.31, 141.72, 144.46, 146.73, 150.32 and 151.45 (Ar-C’s); MS (m/z): [M+], 351.15, [M + 2], 353.15.

2.2.2.2 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (23)

FT-IR (KBr): 1590 (C⚌N), 1505 (C⚌C), 1395 (C—N), 660 (C—S), 841 (C—Cl), 3021 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.23 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.54 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.29 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.15–8.01 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.3 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (24)

FT-IR (KBr): 1593 (C⚌N), 1512 (C⚌C), 1397 (C—N), 665 (C—S), 922 (C—Cl), 921 (C-F), 3070 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.31 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.81 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.37 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.76–8.85 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.4 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (25)

FT-IR (KBr): 1591 (C⚌N), 1512 (C⚌C), 1369 (C—N), 681 (C—S), 854 (C—Cl), 3059 (Ar C—H), 1558 (N⚌O, asymmetric), 1341 (N⚌O, symmetric); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.33 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 4.01 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.73 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.70–8.56 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.5 2,3-Dihydro-2-(2,4-fluorophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (26)

FT-IR (KBr): 1602 (C⚌N), 1518 (C⚌C), 1403 (C—N), 691 (C—S), 856 (C—Cl), 919 (C-F), 3060 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.45 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.76 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.51 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.66–8.61 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.6 2,3-Dihydro-2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (27)

FT-IR (KBr): 1592 (C⚌N), 1526 (C⚌C), 1382 (C—N), 688 (C—S), 945 (C—Cl), 3020 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.43 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.99 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.62 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.90–8.96 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.7 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (28)

FT-IR (KBr): 1596 (C⚌N), 1518 (C⚌C), 1388 (C—N), 667 (C—S), 915 (C—Cl), 3452 (Ar—OH), 3024 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 4.72 (s, 1H, Ar—OH), 5.23 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.51 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.28 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.20–8.19 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.8 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-methylphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (29)

FT-IR (KBr): 1588 (C⚌N), 1516 (C⚌C), 1390 (C—N), 678 (C—S), 888 (C—Cl), 2935 (Alkyl C—H), 3022 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 2.38 (s, 3H, Ar—CH3), 4.95 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.32 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.11 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.10–8.09 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.9 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (30)

FT-IR (KBr): 1586 (C⚌N), 1519 (C⚌C), 1395 (C—N), 666 (C—S), 912 (C—Cl), 1219 (—O—CH3), 3045 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 3.88 (s, 3H, Ar—OCH3), 5.10 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.53 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.26 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.52–7.83 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.10 2,3-Dihydro-2-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (31)

FT-IR (KBr): 1600 (C⚌N), 1515 (C⚌C), 1398 (C—N), 665 (C—S), 896 (C—Cl), 1222 (—O—CH3), 3420 (Ar—OH), 3045 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 3.80 (s, 3H, Ar—OCH3), 4.91 (s, 1H, Ar—OH), 4.99 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.32 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.06 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.69–8.10 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.11 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-dimethylaminophenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (32)

FT-IR (KBr): 1651 (C⚌N), 1519 (C⚌C), 1391 (C—N), 671 (C—S), 910 (C—Cl), 1205 (—N(CH3)2), 3048 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 3.18 (s, 6H,-N(CH3)2, 5.28 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.60 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.41 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.65–8.07 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.12 2,3-Dihydro-2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (33)

FT-IR (KBr): 1615 (C⚌N), 1512 (C⚌C), 1329 (C—N), 682 (C—S), 1229 (—O—CH3), 3095 (Ar C—H).; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 3.83 (s, 3H, Ar—OCH3), 3.88 (s, 3H, Ar—OCH3), 5.01 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.31 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.11 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.85–8.06 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.13 2,3-Dihydro-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (34)

FT-IR (KBr): 1599 (C⚌N), 1508 (C⚌C), 1371 (C—N), 1226 (—O—CH3), 694 (C—S), 901 (C—Cl), 3014 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 3.70 (s, 6H, 2× Ar—OCH3), 3.95 (s, 3H, Ar—OCH3), 5.05 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.29 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.10 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.78–8.12 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.14 2,3-Dihydro-2-(pyridin-2-yl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (35)

FT-IR (KBr): 1595 (C⚌N), 1517 (C⚌C), 1396 (C—N), 672 (C—S), 886 (C—Cl), 1136 (—O—CH3), 3025 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.03 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.29 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.12 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.85–8.14 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.15 2,3-Dihydro-2-(pyridin-3-yl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (36)

FT-IR (KBr): 1602 (C⚌N), 1504 (C⚌C), 1387 (C—N), 676 (C—S), 865 (C—Cl), 3031 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.51 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.77 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.56 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.45–8.49 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.16 2,3-Dihydro-2-(pyridin-4-yl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (37)

FT-IR (KBr): 1610 (C⚌N), 1517 (C⚌C), 1391 (C—N), 692 (C—S), 859 (C—Cl), 3171 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.11 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.49 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.16 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.18–8.28 (10H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.17 2,3-Dihydro-2-(4-thienyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (38)

FT-IR (KBr): 1595 (C⚌N), 1525 (C⚌C), 1395 (C—N), 671 (C—S), 891 (C—Cl), 3012 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.29 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.72 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.49 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.10–8.12 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.18 2,3-Dihydro-2-(2-furfuryl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (39)

FT-IR (KBr): 1583 (C⚌N), 1511 (C⚌C), 1385 (C—N), 699 (C—S), 875 (C—Cl), 3129 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 5.58 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.55 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.34 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.95–8.11 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.19 2,3-Dihydro-2-(2-pyrrolyl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (40)

FT-IR (KBr): 1592 (C⚌N), 1527 (C⚌C), 1399 (C—N), 682 (C—S), 917 (C—Cl), 3321 (N—H), 3011 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 10.09 (s, 1H, —NH), 5.25 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.56 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.42 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 6.87–8.15 (9H, Ar—H).

2.2.2.20 2,3-Dihydro-2-(pyrazol-5-yl)-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (41)

FT-IR (KBr): 1588 (C⚌N), 1522 (C⚌C), 1387 (C—N), 669 (C—S), 911 (C—Cl), 3326 (N—H), 3051 (Ar C—H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 10.25 (s, 1H, N—H), 5.51 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.54 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), 3.21 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b), 7.28–8.31 (8H, Ar—H).

2.3 Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial (antibacterial and antifungal) activities of the novel chloropyrazine clubbed benzothiazepines (22–41) was evaluated against selected bacterial and fungal strains using standard experimental procedures as described in the literature (Vegesna et al., 2017). The standard strains were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and Gene Bank, Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh, India. The bacterial strains selected for the study were Bacillus subtilis (ATCC-60511), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC-11632), Escherichia coli (ATCC-10536), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC-10145) whereas the fungal strains include Aspergillus niger (ATCC-6275) and Candida tropicalis (ATCC-1369) respectively. Ciprofloxacin was used as positive control for antibacterial studies and fluconazole for antifungal activity. Antibacterial activity was performed using nutrient agar medium whereas Potato Dextrose-Agar medium was used for antifungal testing. 2.048 mg of each test compound was taken in vials separately. Then 2 mL of methanol was added. Thus, a solution with a concentration of 1.024 mg/mL was obtained. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and the results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments. The microbial strains were grown at 37 °C in their respective nutrient medium and diluted in sterile nutrient broth medium to get a suspension containing 107 cells/mL and this suspension was used as the inoculum. All the test tubes were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. A similar experiment with inoculum, medium and methanol without compound was furthermore performed to confirm that there is no inhibitory effect of methanol used for the dilutions. The test tube number in which the first sign of the growth of the organism observed was noted using a spectrophotometer. The MIC was determined for all the compounds by taking that concentration used in the test tube number just before the test tube number where the first sign of growth observed (Kasetti et al., 2020).

2.4 Antitubercular activity

Chalcone precursors (1–21) and conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives (22–41) were evaluated for antitubercular activity using the same procedure which we described in our previous paper (Kishor et al., 2017, Lokesh et al., 2019a,b, Palleapati et al., 2019) on Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strain (procured from National Institute of Tuberculosis, Chennai, India) using pyrazinamide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as reference drug. Broth dilution assay was employed to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each compound. All the test compounds were dissolved separately in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, (Merck Life Sciences Private Limited, Mumbai, India) and then diluted twice at the required concentration. A frozen culture in Middle brook 7H9 broth added with 10% albumin-dextrose-catalase and 0.2% glycerol (Himedia, Mumbai, India) was melted and diluted in broth to 105 cfu mL−1 (colony forming unit/mL) dilutions. The final concentration of DMSO in the assay medium was 1.3%. Then, each U-tube was inoculated with 0.05 mL of standardized culture and incubated at 37 °C for 21 days. The growth in the U-tubes was compared with visibility in opposition to a negative control (without drug and inoculum), positive control (without drug), and with standard pyrazinamide. The MIC values obtained in µg/mL were converted into µM for the standard drug pyrazinamide and the target compounds (2–41) in order allow comparison in molecular level.

2.5 Cytotoxic activities

DU-145 (prostate cancer) and normal liver (L02) cell lines were obtained from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. DMEM (Dulbeccos Modified Eagels Medium), MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide], Trypsin, EDTA were purchased from Sigma chemicals (St.Louis,MO). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Arrow Labs, 96 well flat bottom tissue culture plates were purchased from Tarson. The in vitro cytotoxic activity was performed for both chalcones (2–21) and benzothiazepines (22–41) on prostate cancer cell lines (DU-145) by Mosmann’s MTT assay (Mosman, 1983) and their IC50 values were determined. The cytotoxic activity of the target compounds was compared with the standard drug methotrexate (Mtx). In principle, the assay is based on the reduction of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) to formazan (blue-purple colored) product, due to the action of mitochondrial reductase enzyme inside the living cells. DU-145 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) at 37 °C and humidified at 5% CO2. The test compounds (2–41) were dissolved in 0.1% DMSO to make their stock solutions. From these stock solutions, different dilutions of the compounds were made with sterile water to attain the required final concentrations. Briefly, the cells were placed on 96-well plates at 100 µL total volume with a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and were allowed to adhere for 24 h. Later, the medium was replaced with fresh media containing different dilutions of the test compounds and allowed to incubate for another 48 h at 37 °C in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) medium. Afterwards, the medium was replaced with 90 μL of fresh DMEM without FBS. The wells were treated with 10 μL of MTT reagent (5 mg/mL of stock solution in DMEM without FBS) and incubated at 37 °C for 3-–4 h. The formed blue crystals of formazan were dissolved in 200 μL of DMSO, and the optical density was determined at 570 nm using micro plate reader. Assay was carried out in triplicate for three independent experiments. The results had good reproducibility between replicate wells with standard errors below 10%. The cytotoxic activity results measured as IC50 values in µg/mL were converted into µM. All the compounds were also evaluated for their cytotoxicity on normal human liver cell lines (L02) to determine their toxicity by using the identical protocol as described above.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemistry

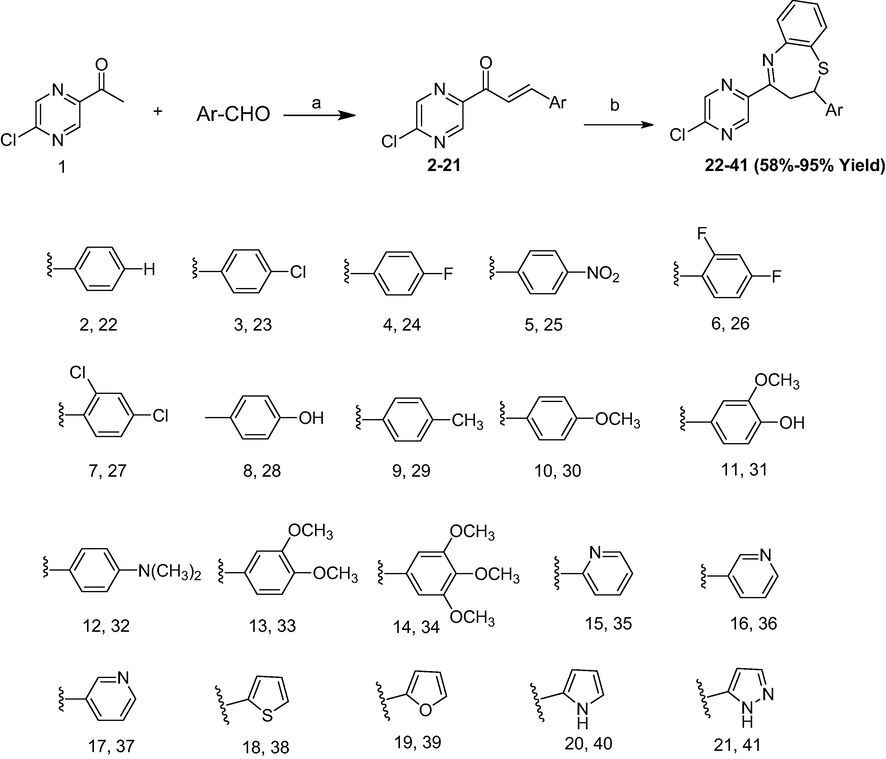

Choloropyrazine based chalcones (2–21) and conjugated 1,5-benzothiazepines (22–41) described here were synthesized following the synthetic routes outlined in Scheme 1. To prepare chalcones 2–21, 2-acetyl-5-chloropyrazine was treated with substituted aromatic and heteroaromatic aldehydes in ethanol under basic conditions to obtain yields between 55% and 97% (Vegesna et al., 2017). Intermediates 2–21 were refluxed with 2-aminothiophenol to obtain target benzothiazepines 22–41 with yields between 58% and 95% (Table 1). The compound 22 was analyzed for molecular formula C19H14ClN3S, m.p. 166–168 °C, well supported by a M+ peak at m/z 351.85 and also a satellite peak at m/z 353.85 with 3:1 intensity in its electron spray ionization mass spectrum. The FT-IR spectrum (cm−1) of the compound 22 showed the characteristic bands at 1584 (C⚌N), 1510 (C⚌C), 1395 (C—N), 663 (C—S), 844 (C—Cl), and 3032 (Ar C—H). The 1H NMR spectrum of compound 22 showed three characteristic peaks of C2-H and C3-CH2 protons of 1,5-benzothiazepine ring at 5.11 (dd, J2,3a = 5.1 Hz, J2,3b = 12 Hz, 1H, C2-H), 3.52 (dd, J3a,3b = 14.4 Hz, J3a,2 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3a), and 3.21 (t, J3b,3a = J3b,2 = 12.9 Hz, 1H, C3-H-3b). The spectrum also accounted for the other twelve aromatic protons in between δ 7.19–8.22. The 13C NMR spectrum of compound 22 accounted for all the carbons whose resonance appeared at the following δ values: 50.15 (C-2), 40.24 (C-3), 164.66 (C-4), 122.54, 126.44, 127.51, 127.81, 128.80, 133.31, 141.72, 144.46, 146.73, 150.32 and 151.45 (Ar-C’s). The values are consistent with the proposed structure for the compound. Based on the above spectral data and elemental analysis, the structure of compound 22 was confirmed as 2,3-dihydro-2-phenyl-4-(5-chloropyrazin-2-yl)-1,5-benzothiazepine (Fig. 4). Similarly, other 19 compounds exhibited their characteristic spectral features in their FT-IR and 1H NMR spectra. The general structures and physicochemical properties of compounds 22–41 are shown in Table 1.

Synthesis of target compounds (2–21) and (22–41): (a) Ethanol, NaOH, room temperature (b) 2-Aminothiophenol, Piperidine/Ethanol, reflux.

Entry

Ar

% Yield

m.p. °C

22

phenyl

90

166–168

23

4-chlorophenyl

95

155–157

24

4-fluorophenyl

92

171–173

25

4-nitrophenyl

83

185–187

26

2,4-difluorophenyl

79

121–123

27

2,4-dichlorophenyl

88

133–135

28

4-hydroxyphenyl

63

196–198

29

4-methylphenyl

79

148–150

30

4-methoxyphenyl

66

205–207

31

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

73

252–254

32

4-dimethylaminophenyl

91

175–177

33

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

81

166–168

34

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

75

210–212

35

2-pyridinyl

65

211–213

36

3-pyridinyl

58

118–120

37

4-pyridinyl

66

131–133

38

2-thienyl

69

150–152

39

2-furfuryl

80

142–144

40

2-pyrrolyl

75

175–177

41

5-pyrazolyl

82

232–236

Summary of the antibacterial, antifungal, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities of chalcones (2–21) and benzothiazepines (22–41).

3.2 Antimicrobial activity

All the compounds synthesized through this study were evaluated for their antimicrobial, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities employing standard protocols. The compounds were classified into three different categories based on their structural features. Physicochemical properties modulated were based on the “R” group. Electron withdrawing or donating groups on phenyl ring (Tables 2–5) were either substituted at para position (3–5, 8–10 & 12; 23–25, 28–30, and 32), ortho and para positions (6, 7, 26 & 27), or meta & para positions (11, 13, 14, 31, 33 and 34). Bioisosteric substitution of phenyl ring with pyridyl, thienyl, furfuryl, pyrrolyl, and pyrazolyl systems resulted in compounds 15–21 and 35–41 as chalcone and benzothiazepine derivatives. The bold numbers indicate the activity of most potent compounds. The bold numbers indicate the activity of most potent compounds. The bold numbers indicate the activity of most potent compounds. Data presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). All the compounds and the standard drug were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with culture medium containing 0.1% DMSO. The control cells were treated with culture medium containing 0.1% DMSO. The bold numbers indicate the activity of most potent compounds.

Entry

Ar

B. subtilis

S. aureus

E. coli

P. aeruginosa

22

phenyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

23

4-chlorophenyl

82.83

82.83

82.83

82.83

24

4-fluorophenyl

86.52

86.52

86.52

86.52

25

4-nitrophenyl

80.63

80.63

80.63

80.63

26

2,4-difluorophenyl

41.25

41.25

41.25

41.25

27

2,4-dichlorophenyl

38.02

38.02

38.02

38.02

28

4-hydroxyphenyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

29

4-methylphenyl

>200

174.92

>200

>200

30

4-methoxyphenyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

31

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

32

4-dimethylaminophenyl

162.05

>200

>200

>200

33

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

34

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

144.81

144.81

72.40

144.81

35

2-pyridinyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

36

3-pyridinyl

181.38

>200

181.38

>200

37

4-pyridinyl

181.38

181.38

181.38

181.38

38

2-thienyl

178.83

>200

>200

178.83

39

2-furfuryl

>200

>200

>200

>200

40

2-pyrrolyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

41

5-pyrazolyl

>200

>200

>200

>200

Ciprofloxacin

145.71

145.71

72.85

72.85

Entry

Ar

A. niger

C. tropicalis

22

phenyl

181.91

181.91

23

4-chlorophenyl

41.41

41.41

24

4-fluorophenyl

43.26

43.26

25

4-nitrophenyl

40.31

40.31

26

2,4-difluorophenyl

20.62

20.62

27

2,4-dichlorophenyl

19.01

19.01

28

4-hydroxyphenyl

173.98

173.98

29

4-methylphenyl

174.92

174.92

30

4-methoxyphenyl

167.59

>200

31

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

>200

>200

32

4-dimethylaminophenyl

162.05

>200

33

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

38.84

155.37

34

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

36.20

36.20

35

2-pyridinyl

90.69

45.34

36

3-pyridinyl

45.34

45.34

37

4-pyridinyl

>200

90.69

38

2-thienyl

44.70

44.70

39

2-furfuryl

93.61

187.23

40

2-pyrrolyl

>200

187.77

41

5-pyrazolyl

187.23

187.23

Fluconazole

84.14

63.10

#

Ar

MIC values (µM) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv

#

MIC values (µM) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv

2

phenyl

130.78

22

181.89

3

4-chlorophenyl

57.32

23

82.83

4

4-fluorophenyl

60.91

24

43.26

5

4-nitrophenyl

220.93

25

322.54

6

2,4-difluorophenyl

28.50

26

41.25

7

2,4-dichlorophenyl

25.51

27

38.02

8

4-hydroxyphenyl

491.02

28

>500

9

4-methylphenyl

123.69

29

174.92

10

4-methoxyphenyl

116.49

30

167.59

11

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

110.07

31

160.85

12

4-dimethylaminophenyl

444.83

32

324.11

13

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

52.50

33

38.84

14

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

23.89

34

18.10

15

2-pyridinyl

>500

35

>500

16

3-pyridinyl

>500

36

>500

17

4-pyridinyl

>500

37

>500

18

2-thienyl

>500

38

>500

19

2-furfuryl

>500

39

>500

20

2-pyrrolyl

>500

40

>500

21

5-pyrazolyl

>500

41

>500

Pyrazinamide

412.76

#

Ar

DU-145

#

DU-145

2

phenyl

>200

22

122.21 ± 1

3

4-chlorophenyl

>200

23

119.08 ± 2

4

4-fluorophenyl

124.27 ± 1

24

156.82 ± 2

5

4-nitrophenyl

>200

25

>200

6

2,4-difluorophenyl

121.18 ± 2

26

72.19 ± 2

7

2,4-dichlorophenyl

46.03 ± 1

27

99.82 ± 2

8

4-hydroxyphenyl

>200

28

>200

9

4-methylphenyl

>200

29

>200

10

4-methoxyphenyl

>200

30

>200

11

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

>200

31

>200

12

4-dimethylaminophenyl

>200

32

121.54 ± 2

13

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

>200

33

>200

14

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

>200

34

158.39 ± 2

15

2-pyridinyl

>200

35

51.01 ± 1

16

3-pyridinyl

>200

36

>200

17

4-pyridinyl

>200

37

181.38 ± 2

18

2-thienyl

>200

38

>200

19

2-furfuryl

>200

39

>200

20

2-pyrrolyl

>200

40

>200

21

5-pyrazolyl

>200

41

35.10 ± 2

Methotrexate

11 ± 1

3.2.1 Antibacterial activity

Compounds 22–41 were evaluated for their antibacterial activity (Table 2) against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa using ciprofloxacin as standard.

The benzothiazepine series (22–41) (Table 2) overall antibacterial activity ranged from 38 to >200 µM. For compounds 22–25, 28–30, and 32, the para position was substituted with either H (22), Cl (23), F (24), NO2 (25), OH (28), CH3 (29), OCH3 (30), and N(CH3)2 (32). Compound 22 with H substituent showed inactivity with MICs > 200 µM against four bacterial species. Replacing H substituent (22) with electron withdrawing substituents chlorine (Cl) (23) fluorine (F) (24), or nitro (NO2) (25) resulted in MICs between 80 and 86 µM suggesting an improvement in the activity against four bacterial species over compound 22. Changing the para position of electron withdrawing to electron donating groups OH (28), CH3 (29), OCH3 (30), and N(CH3)2 (32), a trend similar to chalcones 8–10 and 12 (Vegnesa et al., 2017) was observed causing a significant loss in potency with MICs between 162 and >200 µM indicating that electron withdrawing groups are favored over donating groups at the para position of the phenyl ring.

Based on our data obtained from compounds 23–25, 28–30, and 32, we decided to synthesize few compounds having electron withdrawing and electron donating groups at ortho/para and meta/positions. As seen in compounds 26 and 27, they showed 2-fold improvement in the antibacterial activity (38.02–41.25 µM) over the compounds 23–25 with electron withdrawing groups (23–25; 80.63–86.52 µM), the most active being compound 27 (MIC 38.02 µM). However, in case of disubstituted chalcones with electron donating groups 31 and 33, it resulted in MICs between > 200 µM, suggesting loss of activity similar to compounds 28–30.

Among the bioisosteres (35–41), there was no improvement in the activity in comparison to the standard ciprofloxacin. The MICs varied between 178- >200 µM. The most potent among all benzothiazepines was compound 27 (MIC 38.02 µM) having two- to four-fold improvement in activity over ciprofloxacin against four bacterial species. Overall, chalcones (Vegesna et al., 2017) fared better over benzothiazepine derivatives. Comparing between the two series, it can be inferred that in chalcone and benzothiazepine series, physicochemical property was modulated by electron withdrawing groups in ortho/para positions thereby improving the antibacterial activity.

3.2.2 Antifungal activity

The antifungal activity (Table 3) of benzothiazepine series (22–41) ranged from 19 to >200 µM. Compound 22 with H substituent showed the lowest antibacterial activity with MIC of 181 µM against two fungal species in comparison to compounds 23–34. Replacing H substituent (22) with electron withdrawing substituents chlorine (Cl) (23), fluorine (F) (24), or nitro (NO2) (25) resulted in MICs between 40 and 43 µM suggesting 4.2–4.5-fold improvement in the activity against two fungal species, respectively, over compound 22. Changing the para position from electron withdrawing to electron donating groups OH (28), CH3 (29), OCH3 (30), and N(CH3)2 (32) resulted in a trend similar to chalcones 8–10 and 12 causing a significant drop in the activity with MICs between 162 and 174 µM against A. niger and 173.98–>200 µM against C. tropicalis.

Electron withdrawing groups at ortho/para positions as seen in compounds 26 and 27 showed two-fold improvement in the antibacterial activity (19.01–20.62 µM) over compounds 23–25 with electron withdrawing groups (23–24; 40.31–43.26 µM). Compounds 26 & 27 (MICs 20.62 & 19.01 µM) had similar antifungal activity. However, in case of electron donating groups 31 (meta/para) and 33 (meta/para), it resulted in MICs between 38.84- >200 µM with compound 33 (MIC 38.84 µM) having better activity against A. niger over compound 30 (MIC 167.59 µM vs A. niger).

The MICs of bioisosteres 35–41 varied between 44 and 751 µM. Among the six-membered pyridine ring containing bioisosteres (35–37), compound 36 showed the best activity of 45.34 µM. Although among five-membered heterocycles, the 2-thienyl containing benzothiazepine 38 showed the best activity of 44.70 µM; it was comparatively less than standard fluconazole. The most potent among all benzothiazepines identified was compound 27 (MIC 19.01 µM) having three- to four-fold improvement in activity over fluconazole. Overall, benzothiazepines were found to have comparable activity with chalcones (Vegesna et al., 2017).

3.3 Antitubercular activity

Chalcone (2) with H substituent showed the modest antifungal activity with MIC 130.78 µM against M. tuberculosis (Table 4). Replacing H substituent (2) with electron withdrawing substituents chlorine (Cl) (3) and fluorine (F) (4) resulted in MICs between 57 and 60 µM suggesting nine-fold enhancement in the activity against two fungal species. Substitution of halogens with a nitro group 5 resulted in four-fold decrease in activity over 3 and 4. It was observed that compounds 8, 9, 10, and 12 having electron donating groups caused a significant drop in the activity (MICs 116–491 µM).

Having electron withdrawing groups at ortho and para position of phenyl ring resulted in further improvement in antitubercular activity by two-fold (7 vs 3, MICs 25.51 vs 57.32 µM; 6 vs 4, MICs 28.50 vs 60.91 µM). Substituting meta and para position with electron donating groups (compounds 11 and 13) showed modest activity (MICs 52–110 µM), with compound 13 having better activity over compound 11. Interestingly, substituting the para and the two meta positions with methoxy substituent 14 improved the activity to 23.89 µM. Compound 14 was identified as the most potent of all the synthesized chalcones having 17-fold improved activity over pyrazinamide (MIC 412.76 µM). The next in potency among the chalcone series was compound 7 having MIC of 25.51 µM. Bioisoster-based chalcones 15–21 did not show any improvement in activity with MICs of 521–1095 µM.

The benzothiazepine series (22–41) fared slightly better than the chalcones (Table 4). The overall antitubercular activity ranged from 18 to 1497 µM. Compound 22 with H substituent showed the modest antibacterial activity with MIC of 181.89 µM. Substituting H substituent (22) with electron withdrawing substituents chlorine (Cl) (23) and fluorine (F) (24) resulted in MICs between 43 and 82 µM, suggesting two- to + improvement in the activity against M. tuberculosis over compound 22. However, inserting a 4-nitro (25) substituent surprisingly proved to be deleterious for the activity in comparison to compounds 23 and 24. This trend was found to be similar to chalcones 3, 4 in comparison to 5. Changing the para position from electron withdrawing to electron donating groups OH (28), CH3 (29), OCH3 (30), and N(CH3)2 (32) resulted in attenuation in activity with MICs between 167 and >500 µM, which highlights the importance of electron withdrawing group on the potency.

Electron withdrawing groups at ortho/para positions as seen in compounds 26 and 27 showed either similar or two-fold improvement in the antitubercular activity (38.02–41.25 µM) over the compounds 23–25 with electron withdrawing groups (23–24; 43.26–82.83 µM), the most active being compound 27 (MIC 38.02 µM). Additionally, in case of electron donating groups 31 (meta/para), 33 (meta/para), it resulted in MICs between 38.84 and 160.85 µM, with compound 33 having 4.3-fold better activity over compound 30 (MIC 167.59 µM). Interestingly, compound 34 having three methoxy groups at positions 3, 4, and 5 on the phenyl ring resulted in two-fold improvement in activity over compound 33, a trend found similar in chalcones (14 vs 13).

Introducing bioisosteric replacement for phenyl ring did not show any improvement in MICs as compounds 35–41 displayed inactivity with MICs > 500 µM. The activity trend of benzothiazepines were similar to chalcones (27 vs 7 and 34 vs 14). The most potent compound identified was 34 (MIC 18.01 µM) having 23-fold improvement in activity over pyrazinamide. Overall, benzothiazepines were found to have antitubercular activity comparable with chalcones (34 vs 14; MICs 18.01 vs 23.89 µM).

3.4 Cytotoxic activities

All the 40 compounds were evaluated for their cytotoxic activity against prostate cancer cell line, DU-145, employing MTT assay (Table 5). Among the chalcone series, compound 7 was found to be the most potent with IC50 46.03 ± 1 µM, whereas in benzothiazepine series, compound 41 had 1.3-fold better activity over 7 with the IC50 of 35.10 ± 2 µM. The activity of these compounds was found to be 3–4–fold less than the standard, methotrexate (IC50 = 11 ± 1 µM). The compounds 4, 6, 26, and 35 were next in activity with IC50 values 124.27 ± 1, 121.18 ± 2, 72.19 ± 2 and 51.01 ± 1 µM, respectively. All the other compounds exhibited modest to inactivity with MICs ranging from 99.82 ± 2 to > 200 µM. The structure activity relationship (SAR) features of chalcones and benzothiazepines indicated that electron withdrawing group (Cl) at ortho and para positions (7) and 5-pyrazolyl heterocyclic ring (41) played a key role in cytotoxic activity. The compounds were also tested against the human normal liver cells (L02) and were found to be less selective towards this cell type as the IC50 is beyond the highest concentration tested. (Table 6). A summary of the antibacterial, antifungal, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities of chalcones (2–21) and benzothiazepines (22–41) is depicted in Fig. 4. Data presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). All the compounds and the standard drug were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with culture medium containing 0.1% DMSO. The control cells were treated with culture medium containing 0.1% DMSO.

Entry

Ar

L02

#

L02

2

phenyl

>50

22

>40

3

4-chlorophenyl

>50

23

>40

4

4-fluorophenyl

>50

24

>40

5

4-nitrophenyl

>50

25

>40

6

2,4-difluorophenyl

>50

26

>40

7

2,4-dichlorophenyl

>50

27

>40

8

4-hydroxyphenyl

>50

28

>40

9

4-methylphenyl

>50

29

>40

10

4-methoxyphenyl

>50

30

>40

11

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl

>50

31

>40

12

4-dimethylaminophenyl

>50

32

>40

13

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl

>50

33

>40

14

3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl

>50

34

>40

15

2-pyridinyl

>50

35

>40

16

3-pyridinyl

>50

36

>40

17

4-pyridinyl

>50

37

>40

18

2-thienyl

>50

38

>40

19

2-furfuryl

>50

39

>40

20

2-pyrrolyl

>50

40

>40

21

5-pyrazolyl

>50

41

>40

Methotrexate

–

4 Conclusions

In our ongoing projects on the synthesis of compounds with potential antimicrobial, antitubercular, and cytotoxic activities, we have here reported 20 new compounds bearing benzothiazepine nucleus and evaluated our 20 previously reported chalcones for antitubercular and cytotoxic activities. Biological data indicated that benzodiazepines demonstrated excellent antifungal and antitubercular activities. It was observed that the electronic property (electron withdrawing and electron releasing) of the substituents on the phenyl ring was instrumental for the difference in the potency of the compounds. For instance, among benzothiazepines, electron withdrawing groups resulted in excellent antimicrobial and antifungal activity. Structure activity relationship studies of chalcones indicated that electronic properties did not play a key role for antitubercular activities as evident by compounds 7 and 14 whereas a similar phenomenon was observed for benzothiazepine 34. None of the compounds showed any improvement in cytotoxic activity over the standard drug methotrexate. All the compounds were found to be relatively less selective towards the human normal liver cell line LO2. Further studies are under progress to assess the computational binding characteristics of chalcones and benzodiazepines, which can give a fair understanding of newer analogs.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to acknowledge Vignan Pharmacy College, Vadlamudi, Andhra Pradesh, India for providing the lab facilities and chemicals for this work. R.R.B would like to thank the Dean’s office of College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Ajman University, UAE for their support in preparation of this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Synthesis of new isoxazole-, pyridazine-, pyrimidopyrazines and their anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Med. Chem.. 2018;14:356-371.

- [Google Scholar]

- 5-Alkylamino-N-phenylpyrazine-2-carboxamides: design, preparation, and antimycobacterial evaluation. Molecules.. 2020;25:1561.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and in vitro anti breast cancer activity of some novel 1, 5-benzothiazepine derivatives. J. Serb. Chem. Soc.. 2012;77:725-731.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, antimicrobial and antiinflammatory activity of N-pyrazolyl benzamide derivatives. Med. Chem.. 2015;5:521-527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid-phase synthesis and biological evaluation of a parallel library of 2, 3-dihydro-1, 5-benzothiazepines. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2008;16:7691-7697.

- [Google Scholar]

- The expedient synthesis of 1, 5-benzothiazepines as a family of cytotoxic drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2008;18:114-119.

- [Google Scholar]

- 1, 5-Benzothiazepine, a versatile pharmacophore: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2008;43:2279-2290.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial studies of novel ONO donor hydrazone Schiff base complexes with some Divalent Metal (II) ions. Arab. J. Chem.. 2020;13:6559-6567.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antipellagric action of pyrazme-2, 3-dicarboxylic acid and pyrazine monocarboxylic acid. South. Med. J.. 1939;32:793-795.

- [Google Scholar]

- Substituted N-(pyrazin-2-yl) benzenesulfonamides; Synthesis, anti-infective evaluation, cytotoxicity, and in silico studies. Molecules.. 2020;25:138.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2, 6-Diamino-3, 5-diaryl-1, 4-pyrazine derivatives as novel antioxidants. Synthesis.. 2001;2001:0768-0772.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2-Pyrazine-PPD, a novel dammarane derivative, showed anticancer activity by reactive oxygen species-mediate apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress in gastric cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol.. 2020;881:173211

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of bis-[1, 5]-benzothiazepines. J. Chem. Pharm. Res.. 2016;8:250-254.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2H-Pyrrolo [3, 4-b][1, 5] benzothiazepine derivatives as potential inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Il Farmaco.. 2005;60:385-392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, reactions, and biological activity of 1, 4-thiazepines and their fused aryl and heteroaryl derivatives: a review. J. Sulfur. Chem.. 2011;32:623-690.

- [Google Scholar]

- El-Bayouki, K.A., 2013. Benzo [1, 5] thiazepine: Synthesis, reactions, spectroscopy, and applications. Org. Chem. Int. 2013.

- Etaiw, S.E.H., Marie, H., Elsharqawy, F.A., 2020. Structure and characterization of organotin bimetallic supramolecular coordination polymers based on copper cyanide building blocks and pyrazine or pyrazine‐2‐carboxylic acid as new promising anticancer agents. Appl. Organomet. Chem. e5831.

- Effects of a tranquilizer and two antidepressants on learned and unlearned behaviors. J. Pharm. Sci.. 1970;59:964-968.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis and anticancer activity of N-(1-(4-(dibenzo [b, f][1, 4] thiazepin-11-yl) piperazin-1-yl)-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2017;27:4140-4145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postmortem distribution of the novel antipsychotic drug quetiapine. J. Anal. Toxicol.. 2004;28:264-268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and antitubercular evaluation of some new 5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-thiol derived Schiff bases. Rev. Roum. Chim.. 2020;65:771-776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of clentiazem in patients with essential hypertension: results of an early pilot test. Clin. Cardiol.. 1991;14:53-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological evaluation of some novel pyrazole, isoxazole, benzoxazepine, benzothiazepine and benzodiazepine derivatives bearing an aryl sulfonate moiety as antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Arab. J. Chem.. 2019;12:2091-2097.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitubercular evaluation of isoxazolyl chalcones. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci.. 2017;8:730-735.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chalcones and their pyrazine analogs: synthesis, inhibition of aldose reductase, antioxidant activity, and molecular docking study. Monatsh. Chem.. 2018;149:921-929.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel pyrazine analogs of chalcones: synthesis and evaluation of their antifungal and antimycobacterial activity. Molecules. 2015;20:1104-1117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel halogenated pyrazine-based chalcones as potential antimicrobial drugs. Molecules. 2016;21:1421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, and antiviral activities of 1, 5-benzothiazepine derivatives containing pyridine moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;125:657-662.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel pyrimidine derivatives from 2, 5-dichloro-3-acetylthienyl chalcones as antifungal, antitubercular and cytotoxic agents: Design, synthesis, biological activity and docking study. Asian. J. Chem.. 2019;19:310-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, Biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of new pyrazolines as an antitubercular and cytotoxic agents. Infect. Disord-Drug. Targets. (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Infectious Disorders). 2019;19:310-321.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological activity of novel 2, 5-dichloro-3-acetylthiophene chalcone derivatives. Indian. J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2017;51:s679-s690.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel tribenzylaminobenzolsulphonylimine based on their pyrazine and pyridazines: Synthesis, characterization, antidiabetic, anticancer, anticholinergic, and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;93:103313

- [Google Scholar]

- Mangrolia, U., Osborne, W.J., 2020. Staphylococcus xylosus VITURAJ10: Pyrrolo [1, 2α] pyrazine-1, 4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl)(PPDHMP) producing, potential probiotic strain with antibacterial and anticancer activity. Microb. Pathog. 104259.

- Design and synthesis of 5-methylpyrazine-2-carbohydrazide derivatives: A new anti-tubercular scaffold. Arab. J. Chem.. 2017;10:41-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of indane-Based 1, 5-benzothiazepines derived from 3-Phenyl-2, 3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one and antimicrobial studies thereof. J. Heterocyclic. Chem.. 2017;54:3282-3293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods.. 1983;65:55-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on a new 1, 5-benzothiazepine derivative (CRD-401): III. Effects of optical isomers of CRD-401 on smooth muscle and other pharmacological properties. Jpn. J. Pharmacol.. 1972;22:467-478.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and antitubercular evaluation of some new isoxazole appended 1-carboxamido-4, 5-dihydro-1H-pyrazoles. J. Res. Pharm.. 2019;23:156-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Syntheses of 1, 5-Benzothiazepines: Part-50: 8-Substituted 2, 3/2, 5-dihydro-2, 4-diaryl-1, 5-benzothiazepines as Potential Antimicrobial Agents. Asian. J. Chem.. 2018;30:767-770.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave assisted synthetic approach of new pyridine based benzothiazepines: their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Curr. Microw. Chem.. 2016;3:212-218.

- [Google Scholar]

- A facile synthesis of substituted 2-(5-(Benzylthio)-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-yl) pyrazine using microwave irradiation and conventional method with antioxidant and anticancer activities. J. Heterocyclic. Chem.. 2019;56:859-866.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benzothiazepines: chemistry of a privileged scaffold. RSC. Adv.. 2015;5:70619-70639.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fused 1, 5-benzothiazepines from o-aminothiophenol and its derivatives as versatile synthons. Acta. Chim. Slov.. 2014;61:651-680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expansion of chemical space based on a pyrrolo [1, 2-a] pyrazine core: Synthesis and its anticancer activity in prostate cancer and breast cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2020;188:111988

- [Google Scholar]

- Alkylamino derivatives of N-benzylpyrazine-2-carboxamide: synthesis and antimycobacterial evaluation. MedChemComm.. 2015;6:1311-1317.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antimycobacterial evaluation of N-substituted 5-chloropyrazine-2-carboxamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2013;23:3589-3591.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities of some novel isoxazole ring containing chalcone and dihydropyrazole derivatives. Molecules.. 2020;25:1047.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, biological and computational evaluation of novel 2, 3-dihydro-2-aryl-4-(4-isobutylphenyl)-1, 5-benzothiazepine derivatives as anticancer and anti-EGFR tyrosine kinase agents. Anti-Cancer. Agent. Med. Chem.. 2020;20:1115-1128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 2-(6-alkyl-pyrazin-2-yl)-1H-benz [d] imidazoles as potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Med. Chem. Res.. 2017;26:1835-1846.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved method for the synthesis of new 1, 5-benzothiazepine derivatives as analogues of anticancer drugs. Molecules.. 1997;2:129-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, cytotoxicity, pharmacokinetic profile, binding with DNA and BSA of new imidazo [1, 2-a] pyrazine-benzo [d] imidazol-5-yl hybrids. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activities of alkyl substituted pyrazine derivatives of chalcones—in vitro and in silico study. Antioxidants.. 2019;8:90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tantawy, E.S., Amer, A.M., Mohamed, E.K., Abd Alla, M.M., Nafie, M.S., 2020. Synthesis, characterization of some pyrazine derivatives as anti-cancer agents: In vitro and in Silico approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 128013.

- Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of 2-Substituted-phenyl-3-N, N-dimethylformamido)-4-methyl-1, 5-benzothiazepine. Chinese. J. Org. Chem.. 2018;38:2731-2735.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of structurally diverse benzoazepines clubbed with coumarins as Mycobacterium tuberculosis agents. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des.. 2012;80:1003-1008.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial evaluation of some novel pyrazine based chalcones. IJAPS. 2017;8(2):11-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and Antifungal Activity of 1, 5-Benzothiazepines Containing 1, 2, 3-Triazole. Chinese. J. Org. Chem.. 2020;40:398-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and anti-proliferative activity evaluation of novel benzo [d][1, 3] dioxoles-fused 1, 4-thiazepines. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;127:599-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of C (3)-1, 2, 4-Triazolyl-1, 5-benzothiazepines. Chinese. J. Org. Chem.. 2019;39:2663-2670.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of some new pyrimidine derivatives as anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic agents. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci.. 2015;6:173-185.

- [Google Scholar]

- A convenient synthesis, reactions and biological activities of some novel thieno [3, 2-e] pyrazolo [3, 4-b] pyrazine Compounds as Anti-microbial and Anti-inflammatory Agents. Curr. Org. Syn.. 2018;15:863-871.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis and evaluation of N-pyrazinylbenzamides as potential antimycobacterial agents. Molecules.. 2018;23:2390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis and anti-mycobacterial evaluation of some new N-phenylpyrazine-2-carboxamides. Chem. Pap.. 2016;70:649-657.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, antimycobacterial activity and in vitro cytotoxicity of 5-chloro-N-phenylpyrazine-2-carboxamides. Molecules.. 2013;18:14807-14825.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102915.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article: