Translate this page into:

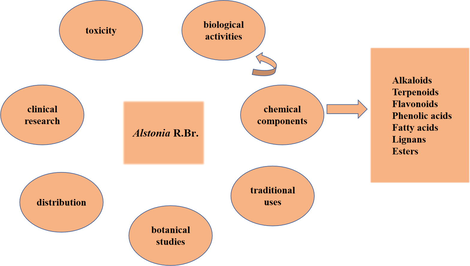

Traditional uses, chemical composition and pharmacological activities of Alstonia R. Br. (Apocynaceae): A review

⁎Corresponding author. cpunmc_zj@163.com (Jie Zhang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Alstonia R. Br. (Apocynaceae) is widely used in the traditional therapeutic systems. Due to its rich natural active ingredients, it is used in China, India, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Africa, Australia and other countries to treat malaria, dysentery, asthma, fever, epilepsy, skin diseases, snake bites, and so on. The aim of this review is to describe in detail the botanical properties, traditional uses, chemical compositions, pharmacological activities and toxicity of the genus Alstonia for analyzing the value of this plant in clinical applications. There was information on the genus Alstonia collected through the internet searches such as Baichain Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Baidu Scholar, PubMed, Wan Fang Database and ACS, etc. The keywords used include genus Alstonia, folk medicinal uses, botanical studies, chemical composition, pharmacological activities, bioactivities and other relevant terminology. The scientific names and geographic location of the genus Alstonia were provided in the Subject Database of the Flora of China, the Plant List (www.theplantlist.org), the WFO Plant List (www.worldfloraonline.org) and the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (http://wcsp.science.kew.org/qsearch.do). Currently, at least 400 compounds were isolated from genus Alstonia, including alkaloids, triterpenes, flavonoids, volatile oils, phenolic acids, etc. Through extensive pharmacological experiments, it was demonstrated that genus Alstonia had good pharmacological effects in vitro and in vivo, including β2AR, vasodilatory, antifungal, antineoplastic, antiplasmodial, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, analgesic, and radioprotective activities, etc. Many studies also confirmed that the combination of the genus Alstonia with other traditional Chinese medicines could improve effectiveness. This review demonstrates that the genus Alstonia has high clinical application and medicinal value, which will bring the attention of pharmacologists and clinicians to the territory of natural products Additionally, bioactivity-related mechanisms and structure–activity relationships of chemical components are not clear. Only by bridging the gap between bioactivity-related mechanisms and structure–activity relationships of chemical components can the development of Alstonia plants be further promoted.

Keywords

Alstonia R. Br. (Apocynaceae)

Chemical components

Biological activities

Traditional uses

1 Introduction

Various natural products exist in nature. And natural products are rich in chemical components with different structure, such as flavonoids, triterpenes, steroids, alkaloids, etc., which are a critical treasure trove for the discovery of new drug lead compounds. In traditional applications, these plants can be used medicinally to treat disease and have great advantages over other chemical drugs, such as Alstonia. The genus Alstonia is a tropical plant with widespread distribution throughout the world, mainly in Africa, Indo-Malaya, Australia, Asia and other regions (Narine et al., 2009; Ku et al., 2011).

Approximately 46 species of the genus Alstonia are known worldwide and can be found at https://wcsp.science.kew.org/qsearch.do, https://www.worldfloraonline.org and https://www.theplantlist.org. Eight of them are located in the regions of Guangdong, Guangxi and Yunnan in China. In traditional medicine, these species are used not only to treat a number of diseases, such as malaria, but also to provide fever-reducing, cough-suppressing and hemostatic effects (Channa et al., 2005; Gandhi and Vinayak, 1990; Wright et al., 1993; Leaman et al., 1995; Kam et al., 1997). Total alkaloids (TA) obtained from Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br. as a new investigational phytopharmaceutical (No. 2011L01436) are registered in advance of clinical application (Pan et al., 2016). TA are also approved by the Chinese Food and Drug Administration for Phase I/II clinical trials (Shang et al., 2010a, 2010b). Additionally, the genus Alstonia could be used in association with other traditional Chinese medicines to maximize effectiveness, such as the combination of Khaya ivorensis A. Chev. and Alstonia boonei De Wild. as antimalarial prophylaxis (Tepongning et al., 2011).

Phytochemical studies have shown that the genus Alstonia represents a treasure trove as a source of phytoconstituents. In excess of 400 compounds have been isolated from this genus (Wang et al., 2009). Chemical investigation of the alkaloidal constituents was undertaken by Sharp (1938) and Elderfield (1942) (Keogh and Shaw, 1943). So far, the most abundant compounds isolated from this genus are monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs), and the non-alkaloid components include flavonoids, terpenes, phenolic acids, volatile oils, and so on. MIAs are the products from the condensation of tryptophan with secologanin. It is the second most abundant metabolite of the genus (De, 2011). After comprehensive analysis of phytochemistry and pharmacology, most of the genus's crude extracts and purified compounds are pharmacologically potent. Beyond that, the genus Alstonia also has different pharmacological activities in different parts. A. scholaris is the majority researched and representative species in the genus Alstonia. Despite extensive work and studies on A. scholaris, the number of precursor molecules and herbal preparations available have been extremely small (Pandey et al., 2020).

There was information on the genus Alstonia collected through the internet searches such as Science Network, PubMed, Baichain Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Baidu Scholar, Wan Fang Database, and ACS, etc. The keywords used include genus Alstonia, folk medicinal uses, botanical studies, chemical composition, bioactivity, secondary metabolites, and other relevant terminology. The scientific names and geographic location of the genus Alstonia were provided in the Subject Database of the Flora of China, the Plant List (https://www.theplantlist.org), and the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (https://wcsp.science.kew.org/qsearch.do).

In this review, a comprehensive compilation of botanical information, traditional uses, phytochemistry, bioactivities and toxicity involved in the genus Alstonia is presented. The purpose of this review is to discover lead compounds from the genus Alstonia that provide potential development value and clinical application value. In addition, a clearer structured review of the structure–activity relationships of chemical compositions is expected to afford a more reliable basis for the pharmacological mechanisms and new drug development of Alstonia.

2 Distribution and botanical studies

Genus Alstonia plants are generally shrubs or trees. All the species of the genus Alstonia are known worldwide, eight of which are located in the Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan regions of China. The names and geographical distribution of the identified 46 species are listed in Table S1.

In accordance with Flora of China, Alstonia is a member of the Apocynaceae family. They are mostly trees and shrubs with milk, and their branches grow on wheels. The leaves are usually in whorls of 3–4(-8), rarely opposite. Lateral veins are numerous, crowded and parallel. Flowers are white, yellow, or red, consisting of multiple flowers forming an umbel-like polyglobulus inflorescence, terminal or nearly terminal. Calyx short, sepals are double-covered imbricate arrangement. There are no interior glands, and the corolla is salver-shaped. Crown tube is cylindrical, expanding above the middle, without corona at the throat. Corolla lobes are covered to the left at the time of the buds (Chinese species). Stamens are separated from the stigma and the anthers are oblong. Ovary is composed of two detached carpels, with multiple ovules per carpel. Flowering style is filiform, whereas stigmas are clubbed. Flower disk consists of 2 ligulate scales, which are alternate with the carpels. Seeds are flat and covered at both ends by long marginal hairs.

A. scholaris is a representative species of the genus Alstonia, which has a typical milky white latex that cuts the bark and flows freely. The genus is distributed primarily in tropical Africa, Asia, and Australia. In the evergreen rainforest of tropical West Africa, Alstonia becomes a tremendous tree, thriving on damp river banks (Adotey et al.,2012).

3 Traditional uses

A number of plants in the genus Alstonia have been used in folk medicine from ancient times. For example, in the tribes of the Indian Gulf Islands, the leaves of Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G. Don are commonly decocted to treat stomach pains (Dagar and Dagar, 1991). In West and Central Africa, A. boonei is regarded as a medicinal plant by local people. A. boonei is widely used in the treatment of malaria, intestinal helminths, rheumatism, hypertension, and so on (Terashima, 2003; Betti, 2004; Abel and Busia, 2005). The flowers of A. scholaris can be used as a CNS depressant (Sood and Thakur, 2015) and also to treat respiratory problems and asthma (Anonymous, 1985). When ear pain, boils and injuries occur, the latex of A. scholaris is combined with oil as a treatment for the disease (Bhardwaj and Gakhar, 2005). Alstonia mairei H. Lév. is used in folklore as an essential medicinal plant for stopping bleeding and dissolving poison (Li et al., 1995; Wang, 2014).

The genus Alstonia bark is most generally used in traditional medicine, but the most commonly used part is the thick bark of mature trees (Adotey et al., 2012). Alstonia's bark has a natural analgesic effect and serves as one of the analgesic herbs (Abbiw, 1990). In daily treatment, the bark not only treats rheumatism, inflammation, pain, malaria, diabetes (mild hypoglycemia), but also exerts anthelmintic, antimicrobial and antibiotic effects (Hadi and Bremner, 2001; Fakae et al., 2000; Kam et al., 1997). The decoction of Alstonia also provides mild antibacterial action and may relieve the soreness involved with malarial fevers (Adotey et al., 2012). The fresh bark of Alstonia is used to make an herbal tincture for snake, rat or scorpion poisoning (Adotey, et al., 2012). The cold infusion is used orally to expel roundworms and nematodes (Abbiw, 1990). Extracts of the leaves have been developed commercially as typical herbal medicines and are also hospital prescription drug, available in pharmacies (Cai et al., 2008). In Table 1, the traditional uses (edible and medicinal) of the genus Alstonia are provided. —: not mentioned.

Alstonia plants

Parts of the plant

Edible methods

Traditional and clinical uses

Reference

Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br.

Ripe fruits

–

Curing for syphilis, insanityand epilepsy

(Jahan et al., 2009)

Milky juice

–

Curing for ulcers, wounds and rheumatic pain

(Varshney and Goyal, 1995)

Bark

Decoction

Curing for falciparum malaria, asthma, hypertension, lung cancer and pneumonia

(Varshney and Goyal, 1995)

Powdered bark

Curing for malaria, diarrhea, and dysentery

(Kirtikar and Basu, 1918; Akhtar et al., 1992)

Leaves

–

Curing cough, chronic bronchitis, asthma, fever and other respiratory infections after infection

(Dey and De, 2011; Sharma et al., 2001)

Flowers

Curing for respiratory problems and asthma

(Anonymous, 1985)

Root

–

Curing for treat gum or dental problems

(Pan et al., 2014)

Latex

Mixed with oil

Curing for earache, boils, and wounds healing

(Bhardwaj and Gakhar, 2005)

Alstonia yunnanensis Diels

Root

–

Curing for headache, fever and hypertension

(Chen et al., 1983)

Alstonia venenata R. Br.

The whole plant

–

Curing for insanity and epilepsy

(Ray and Dutta, 1973)

Alstonia angustifolia A. DC.

Leaves

–

Curing for relapsing fever of spleen area

(Ray and Dutta, 1973)

Alstonia macrophylla Wall. ex G. Don

Leaves and bark

Decoction

Curing for stomachache, skin diseases and urinary infection

(Dagar and Dagar, 1991; Bhargava, 1983)

Leaves

Copra oil mixed with heated leaves

Curing for sprains, bruises, dislocated joints and muscle injuries

(Asolkar and Kakkar, 1992)

Bark

Powdered form

Curing for antipyretic and dysentery

Aid in the menstrual cycle(Changwichit et al., 2011; Chattopadhyay et al., 2004)

Bark

Powdered form mixed with water

Curing for astringent and skin diseases

(Das et al., 2008)

Alstonia boonei De Wild.

Stem bark

Decoction

Curing for astringent, alternative tonic, diarrhea and a febrifuge for relapsing fevers

(Abbiw, 1990)

Leaves and latex

–

Curing for rheumatic and muscular pain and hypertension

(Abbiw, 1990)

Alstonia congensis Engl.

Leaves

Aqueous decoction

Curing for diarrhoea

(Lumpu et al., 2012)

Alstonia mairei H. Lév.

–

–

Curing for haemostasis, disintoxication

(Li et al., 1995; Wang, 2014)

4 Chemical components

In addition to volatile oils, a total of 392 chemical constituents are obtained from genus Alstonia. The chemical composition of Alstonia plants (as shown in Table S2.) involves alkaloids (1–319), triterpenes (320–362), flavonoids (363–379), fatty acid (380), phenolic acids (381–388), lignans (389–391), and ester (392).

The earliest study of the phytochemical composition of Alstonia plants could be dated in the 19th century. In 1875, a new crystalline alkaloid belonging to the aluammiline alkaloids was isolated from the bark of the genus Alstonia, which was named Echitamine (Goodson, 1932). After that, with the development of two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (2D NMR) and quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer (Q-TOF-MS), this technique for the chemical composition of genus Alstonia identification was provided a new method. Until 21st century, with the proposed bioactivity-oriented separation strategies, more bioactive components have been identified (El-Askary et al., 2012). In addition, bioactive-based liquid chromatography-coupled electrospray ionization tandem ion trap/time of flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) technology was also applied to detect bioactive components in Alstonia plants (Hou et al., 2012a).

4.1 Alkaloids (1–319)

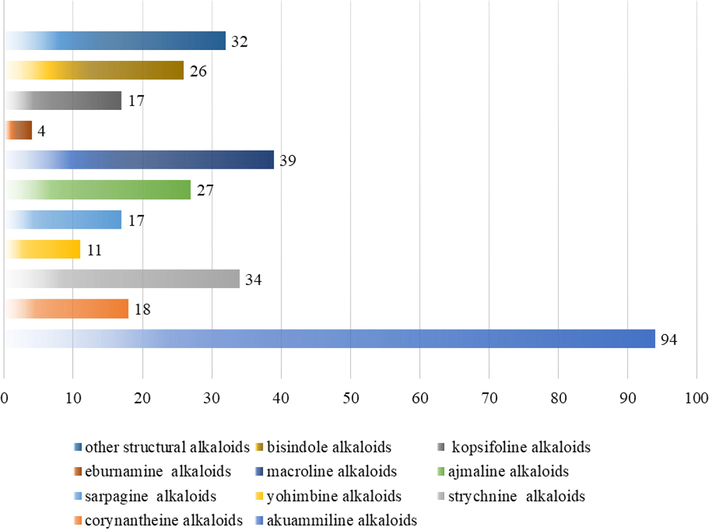

Alkaloids are a highly diverse set of compounds. They are mainly distributed in the Apocynaceae family, such as Alstonia R. Br. Alkaloids are only associated with the presence of nitrogen atoms in heterocyclic rings and are the main active and typical components of genus Alstonia. So far, 319 alkaloids have been obtained in the genus Alstonia, mainly divided into MIAs, bisindole alkaloids and other alkaloids. MIAs constituted a broad and various population of natural products characterized by the combination of indole units with extensively modified monoterpenoid molecules (Zhang et al., 2020). In the genus Alstonia, the MIAs are mainly corynantheine-strychnine alkaloids (1–157), sarpagine alkaloids (158–174), ajmaline alkaloids (175–201), macroline alkaloids (202–240), eburnamine and kopsifoline alkaloids (241–261). Because of their impressive structures and wide range of bioactivities, MIAs were often located on the list of popular molecules in natural product synthesis (Zhang et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2014; Adams et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2016). (Tables 2-5) show that the alkaloids identified from different species of the genus Alstonia. The proportions of the different types with alkaloids in the genus Alstonia are shown in the Fig. 1.

No.

compound

R1

R2

253

Alstomairine D

OCH3

CH3COO

254

Lochnericine

H

H

No.

compound

R1

R2

255

Echitoveniline

H

OH

256

Tabersonine

H

H

257

16-methoxytabersonine

OCH3

H

258

19-hydroxytabersonine

H

OH

259

Vandrikidine

OCH3

OH

260

19-acetoxy‐11-methoxytabersonine

OCH3

CH3COO

261

Vincadifformine

H

macroline‐ajmaline and macroline‐pleiocarpamine type

No.

compound

R1

R2

R3

R4

273

Macralstonine

H

β-H

α-OH

β-CH3

274

O-methylmacralstonine

H

α-H

OCH

CH3

275

Lumusidine B

α-CH3

β-H

β-OH

H

276

Lumusidine C

H

α-H

β-CH2CH3

CH3

277

O-acetylmacralstonine

H

α-H

OCOCH3

CH3

macroline‐akuammiline type

macroline‐corynantheine type

No.

compound

R

Nb

282

Villalstonidine F

H

283

Villalstonine

CH3

284

Villastonine Nb-oxide

CH

Nb-oxide

akuammiline-ajmaline and yohimbine-kopsinine type

No.

compound

R1

R2

R3

310

Angustimaline

H

COCH3

α-OH

311

Angustimaline A

CH3

CHO

α-OH

312

Angustimaline B

CH3

CHO

β-OH

313

Angustimaline C

H

COCH3

β-OH

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Antifertility activity

-amyrin

α-amyrinoral administration of the exact at a dose of 200 mg/day in 60 days did not cause weight loss, while the weight of the test, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and abdominal prostate decreased

In vivo

(Gupta et al., 2002)

Llupiolacetate

Rhazineoral administration of the exact at a dose of 200 mg/day in 60 days did not cause weight loss, while the weight of the test, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and abdominal prostate decreased

In vivo

(Gupta et al., 2002)

Venenative

Yohimbineoral administration of the exact at a dose of 200 mg/day in 60 days did not cause weight loss, while the weight of the test, epididymis, seminal vesicles, and abdominal prostate decreased

In vivo

(Gupta et al., 2002)

Anticancer activity

ASE

the combination of 180 mg/kg of ASE and 8 mg/kg of BCLL showed the maximum antitumor effect

In vivo

(Jagetia and Baliga, 2004)

significant increase in reduced glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase but decrease in lipid peroxidation was measured in ASE administered experimental groups than the carcinogen treatedcontrol.

In vivo

(Jahan et al., 2009)

ASERS

tumors were relieved at 240 mg/kg body weight, where the maximum antitumor effect was observed. As 240 mg/kg ASERS showed toxic manifestations, the next lower dose of 210 mg/kg was considered as the best effective dose

In vitro

(Jagetia and Baliga, 2006)

Echitamine

in vivo researchs with methylanthracene-induced fibroid rats showed that the anticancer activity of echidna extended to the in vivo system and a significant decrease in tumor growth was observed

In vivo

(Baliga, 2010)

Cytotoxic activity

Alstobrogalin

alstobrogalin was weakly cytotoxic towards MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells (IC50 25.3 and 24.1 µM, respectively), but inactive towards MDA-MB-468, SKBR3, and T47D cells (IC50 > 30 µM)

In vitro

(Krishnan et al., 2019)

15-hydroxyangustilobine A

15-hydroxyangustilobine A was the active component (IC50 of 26 μ M in MCF-7 cells). 15 hydroxyangustilobine A was shown to cause cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase (MCF-7 cells) and to trigger apoptosis

In vitro

((Spiegler et al., 2021)

Alstomairine B

demonstrated cytotoxic activity against all tumor cell lines tested (IC50 = 9.2 µM)

In vitro

(Yan et al., 2017)

Alstomairine C

exhibited cytotoxic activity against all tumor cell lines tested with an IC50 value of 13.0 µM

In vitro

(Yan et al., 2017)

Angustilobine C

had moderate cytotoxicity towards drug-sensitive KB and vincristine-resistant at IC50 of 7.76 and 7.33 µg/mL, respectively

In vitro

(Ku et al., 2011)

ScholarisinⅥ

possessed significant cytotoxicities against all tumor cell lines tested, with low IC50 values (<30 μM)

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

Perakine N4-oxide

Raucaffrinoline N4-oxide

Vinorine N4-oxidepossessed higher cytotoxic activities against astrocytoma and glioma cell (CCF-STTG1, CHG-5, SHG-44 and U251) with lower IC50 value than against human skin cancer (SK-MEL-2) and human breast cancer (MCF-7 cells)

In vitro

(Cao et al., 2012)0

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Scholarisin I

possessed significant cytotoxicities against all tumor cell lines tested, with low IC50 values (< 30 μM)

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

Angustilobine B

angustilobine B was cytotoxic to KB cells

In vitro

(Tan et al., 2010)

Alstonine

alstonine was reported to have antitumor effects in transplantable YC8 lymphoma ascites-bearing mice (BALB/C mice) and in Ehrlich ascites carcinoma-bearing swiss mice

In vivo

(Baliga, 2010)

Vincadifformine

Echitovenilinedisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and the IC50 values ranged from 5.6 to 77.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

Tabersonine

Tetrahydroalstoninedisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and the IC50 values ranged from 5.6‐77.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

16- methoxytabersonine

19-acetoxy-11-methoxytabersoninedisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and the IC50 values ranged from 5.6‐13.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

19-hydroxytabersonine

Vandrikidinedisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and the IC50 values ranged from 5.6‐77.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

Isovallesiachotamine

had potent cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and the IC50 values ranged from 5.6‐13.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

Angustilongine A

Angustilongine Bdisplayed significant in vitro growth inhibitory activity against a range of human cancer cell lines, including KB, vincristine-resistant KB, PC-3, LNCaP, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, HT-29, HCT 116, and A549 cells within the range of 0.3‐8.3 Μm

In vitro

(Yeap et al., 2018)

Alstomairine D

Alstomairine Gdisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and IC50 values ranged from 5.6 to 77.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

Lochnericine

Alstomairine Edisplayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and IC50 values ranged from 5.6 to 13.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

Yohimbine-17-O-3′,4′,5′-Trimethoxybenzoate

displayed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells and IC50 values ranged from 5.6 to 13.1 μM

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

(E)-16-formyl-5α-Methoxystrictamine

displayed marked cytotoxicities against all the tumor cell lines tested and IC50 value was low (< 30 μM)

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

Alstomairine D

Alstomairine Eshowed cytotoxicity against A549 lung cancer cells tested. The IC50 of alstomairines D and E ranged from 5.6 to 77.1 μM and 5.6 to 13.1 μM, respectively

In vitro

(Li et al., 2022a, 2022b)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Vasorelaxant activity

Undulifolin

with uleine skeleton showed moderate activity (33.3% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstilobanine A

possessing angustilodine skeleton without an ether linkage showed more potent activity (44.3% at 3 × 105 M)

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstilobanine C

showed moderate activity (28.0% at 3 × 10-5 M) with uleine skeleton

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstilobanine B

with uleine skeleton showed moderate activity (21.2% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

((Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstilobanine E

with an ether linkage showed moderate activity the weakest activity (6.8% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstilobanine D

showed weak activity (10.0% at 3×10-5 M) against phenylephrine (PE, 3 × 107 M)-induced contractions ofthoracic rat aortic rings with endothelium

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstonamic acid

possessing seco skeleton showed a weak activity (35.0% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

6,7-secoangustilobine B

showed weak activity (7.0% at 3 × 10-5 M) against phenylephrine (PE, 3 × 107 M)-induced contractions ofthoracic rat aortic rings with endothelium

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2008)

Alstiphyllanine A

showed vasorelaxant activity against phenylephrine induced contraction of isolated rat aorta (70% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Alstiphyllanine B

had vasorelaxant activity against phenylephrine-induced constriction in isolated rat aorta (35% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Alstiphyllanine C

showed vasorelaxant activity against phenylephrine-induced constriction in isolated rat aorta (40% at 3 × 10 -5 M)

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Alstiphyllanine D

had vasorelaxant activity against phenylephrine-induced constriction in isolated rat aorta (42% at 3 × 10-5 M)

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Vincamajine-17-O-veratrate

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

Vincamajine-17-O-3′,4′,5′-Trimethoxybenzoate

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineI

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineJ

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineL

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineM

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineN

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

AlstiphyllanineO

showed that they relaxed phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2012)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Alstolarine A

exhibited promising vasorelaxant activities against KCl-induced contraction of rat renal arteries with EC50 values of 4.6 µM

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2020)

Alstolarine B

exhibited promising vasorelaxant activities against KCl-induced contraction of rat renal arteries with EC50 values of 6.7 µM

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2020)

Melosline C

exhibited potent vasorelaxant activityon renal arteries with EC50 value of 38.62 μmol·L−1

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2019)

Melosline D

exhibited potent vasorelaxant activityon renal arteries with EC50 value of 41.43 μmol·L−1

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2019)

Alstoschonoid A

showed significant vasorelaxant activity with relaxation rates above 90% at 200 μM and exhibited moderate vasorelaxant activity with IC50 values between 41.87 and 93.30 μM by further studies

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

Alstochonine B

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

Methyl 4- [2-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3- methoxyphenyl) -l (hydroxymethyl) ethyl] ferulate

exhibited significant vasodilatory activity at 200 μM with a relaxation rate of>90% and by further studies showed moderate vasodilatory activity having IC50 values between 41.87 and 93.30 μM

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

(‐) ‐ (7R,7′R,7″R,8S,8′S,8″S)-4′,4″-dihydroxy-3,3′,3′′,5‐tetramethoxy-7, 9′:7′,9-diepoxy-4,8′′-oxy-8, 8′-sesquineolignan-7″,9′′-diol

exhibited significant vasodilatory activity at 200 μM with a relaxation rate of>90% and by further studies showed moderate vasodilatory activity having IC50 values between 41.87 and 93.30 μM

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

(‐) ‐ (7R,7′R,7′′R,8S,8′S,8′′S)-4′,4′′-dihydroxy-3,3′,3′′,5,5′‐pentamethoxy-7,9′:7′,9-diepoxy-4,8′′-oxy-8,8′-sesquineolignan-7′′,9′′-diol

exhibited significant vasodilatory activity at 200 μM with a relaxation rate of>90% and by further studies showed moderate vasodilatory activity having IC50 values between 41.87 and 93.30 μM

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

Alstochonine A

showed moderate vasorelaxant activity (IC50 values of 93.30 ± 10.81)

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2022)

Antifungal activity

Δ3-alstovenine

Δ3-alstovenine at 250–1000 mg/L inhibited the spore germination of most of the tested fungi

In vitro

(Singh et al., 1999)

Tricin-4′-O-β-L-arabinoside

showed significant antifunga activity against salmonella typhimurium (MTCC-98), candida albicans (IAO-109)

In vitro

(Parveen et al., 2010)

The leaves extract of A. scholaris

the extract was applied against eight five fungal strains

In vitro

Altaf et al., 2019

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

The leaves and bark of A. venenata

Fungal studies were conducted on crude extracts of plants to test their fungicidal properties against human pathogens, plant pathogens and industrially important strains of fungi

In vitro

(Ray and Dutta, 1973)

Scholarisin I

demonstrated antifungal activity for two fungi (G. pulicaris and C. nicotianae) and the MIC values were 0.64–0.69 mM

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

ScholarisinⅡ

demonstrated antifungal activity for two fungi (G. pulicaris and C. nicotianae) and the MIC values were 1.37‐1.44 mM

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

ScholarisinIII

demonstrated antifungal activity for two fungi (G. pulicaris and C. nicotianae) and the MIC values were 1.80‐1.91 mM

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

(3R,5S,7R,15R,16R,19E)-scholarisine F

demonstrated antifungal activity for two fungi (G. pulicaris and C. nicotianae) and the MIC values were 1.55‐1.71 mM

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

Antibacterial activity

The crude methanolic extracts of ASE

exhibiting improved and broader spectrum of antibacterial activity

In vitro

(Khan et al., 2013)

Scholarisine T

exhibited significant antibacterial effects on Escherichia coli and MIC value was 0.78 µg/mL.

In vitro

(Yu et al., 2018)

Scholarisine U

showed remarkable antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis and MIC value was 3.12 µg/mL

exhibited significant antibacterial effects on Escherichia coli and MIC value was 0.78 µg/mLIn vitro

(Yu et al., 2018)

Scholarisine V

exhibited significant antibacterial effects on Escherichia coli and MIC value was 0.78 µg/mL.

In vitro

(Yu et al., 2018)

Tricin-4′-O-β-L-arabinoside

showed antibacterial activity against staphylococcus aureus (IAO-SA-22), escherichia coli (K-12)

In vitro

(Parveen et al., 2010)

Antimicrobial activity

Tricin-4′-O-β-L-arabinoside

showed significant antimicrobial activity using agar well diffusion method

In vitro

(Parveen et al., 2010)

The crude extract of AM

antimicrobial activity was exhibited against various strains of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Proteus mirabilis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var mentagrophytes, MicrosporµM gypseum, Streptococcus faecalis and Trichophyton rubrum. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values range from 64 to 1000 µg/ml for bacteria and 32‐128 mg/ml for dermatophytes However, the strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella sp. and Vibrio cholerae demonstrated resistance to the extract treatment up to 2000 µg/ml, while two yeasts were resistant even at a concentration of 128 mg/ml

In vitro

(Chattopadhyay et al., 2004)

ASE

the current study on A. scholaris revealed valuable phytochemical constituents with significant antimicrobial properties and further suggested that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the extracts should be investigated in future studies

In vitro

(Altaf et al., 2019)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Marginal activity

Crude alkaloidal extracts from the roots

crude extracts of alkaloids obtained from plant roots exhibited weak activity against experimental U14 tumors in mice

In vivo

(Chen et al., 1983)

SGLT inhibitory activity

Alstiphyllanine E

indicated inhibitory activity against SGLT1 and SGLT2 with 60.3% and 80.5% inhibition values

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2010)

Burn-amine-17-O-3′,4′,5′-trimethoxybenzoate

indicated inhibitory activity against SGLT1 and SGLT2 with 53.0% and 87.3% inhibition values

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2010)

Alstiphyllanine F

indicated inhibitory activity against SGLT1 and SGLT2 with 65.2% and 103.8% inhibition values

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2010)

AlstiphyllanineD

indicated inhibitory activity agains SGLT1 and SGLT2 with 89.9% and 101.4% inhibition values

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2010)

10-methoxy-N1-methylburnamine-17-O-veratrate

indicated inhibitory activity agains SGLT1 and SGLT2 with 98.5% and 102.6% inhibition values

In vitro

(Arai et al., 2010)

β2AR activity

Z-alstoscholarine

compared with the control, Z-alstoscholarine showed significant effects

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

Akuammidine

compared with the control, akuammidine showed significant effects

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

19,20-(E)-vallesamine

compared with the control, 19,20-(E)-vallesamine showed significant effects

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

E-alstoscholarine

compared with the control, E-alstoscholarine showed significant effects

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

12-hydroxy-echitamidine Nb-oxide (HENO)

compared with the control, HENO showed significant effects

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

Scholaricine

displayed much poorer β2 AR activation

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

Picrinine

displayed much poorer β2 AR activation

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

11-methoxygelsemamide

indicated potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Alstomaline

displayed potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Alloyohimbine

displayed potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

19E-Vallesamine

displayed potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Pseudoyohimbine

indicated potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Picrinine

indicated potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Picralinal

indicated potential activity for β2 AR

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012b)

Spasmolytic activity

The crude extract of

A. scholaris

in isolated rabbit jejunum preparation, the As. Cr produced inhibition of spontaneous and high K+ (80 mM) ‐induced contractions, with respective EC50 values of 1.04 (0.73‐1.48) and 1.02 mg/mL (0.56‐1.84; 95% CI), thus showing spasmolytic activity mediated possibly through calcium channel blockade (CCB)

In vitro

(Shah et al., 2010)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Akuammidine

the EC50 value for the spasmolytic activity was 243.9 µmol/L

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

The total alkaloidal extract of A. scholaris

the EC50 value for the spasmolytic activity of the total alkaloidal extract (500 µg/mL) was 267.5 µmol/L

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

Z-alstoscholarine

the EC50 value for the spasmolytic activity was 137.5 µmol/L

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

19,20-(E)-vallesamine

the EC50 value for the spasmolytic activity was 74.8 µmol/L

In vitro

(Hou et al., 2012a)

Immunostimulating activity

Ethanol extractions of A. scholaris bark

A. scholaris bark aqueous extracts at 50 and 100 mg/kg of bw were able to stimulate non– specific immune response

In vivo

(Iwo et al., 2000)

Alstiphyllanine A

displayed intermediate-level antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Echitamine

exhibited moderate activity against P. falciparum K-1 (IC50 < 30 µM); showed moderate activity against P. falciparum NF54 A19A (IC50 values of 11.07 µM)

In vitro

(Kanyanga et al., 2019)

6,7-seco-angustilobine B

exhibited moderate activity against P. falciparum K-1 (IC50 < 30 µM); showed moderate activity against P. falciparum NF54 A19A (IC50 values of 21.26 µM)

In vitro

(Kanyanga et al., 2019)

β-amyrin

exhibited moderate activity against P. falciparum K-1 (IC50 < 30 µM); showed moderate activity against P. falciparum NF54 A19A (IC50 values of 40.70 µM)

In vitro

(Kanyanga et al., 2019)

The combination stem barks of K. ivorensis and A. boonei

exhibited antimalarial activity in a mouse model of malaria. In mice treated with the combination therapy at 200 mg/kg/day, parasitemia values were 6.2% ± 1.7 and 6.5% ± 0.8 compared to 10.8% ± 1.3 and 12.0% ± 4.0 in the control group (p < 0.01). Doubling the dose of the extract did not significantly increase the parasitemia inhibition

In vitro

(Tepongning et al., 2011)

Alstiphyllanine B

displayed intermediate-level antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Alstiphyllanine C

displayed intermediate-level antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Alstiphyllanine D

displayed intermediate-level antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum

In vitro

(Hirasawa et al., 2009)

Boonein

boonein exhibited anti-P. falciparum K-1 activity with IC50 >64µM; boonein did not response to P. falciparum NF54 A19A

In vitro

(Kanyanga et al., 2019)

Akuammicine N-oxide

had antiplasmodial activityagainst Plasmodium falciparum (K1, multidrug-resistance strain) with IC50 = 63.2 µg/mL

In vitro

(Salim et al., 2004)

Nb-demethylalstogustine

had antiplasmodial activityagainst Plasmodium falciparum (K1, multidrug-resistance strain) with IC50 = 6.75 µg/mL

In vitro

(Salim et al., 2004)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

AChE inhibitory activity

Alstolarine B

displayed moderate AChE inhibitory activity at an IC50 value of 19.3 μM (IC50 for control tacrine = 0.3 μM).

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2020)

Naresuanoside

displayed moderate AChE and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) inhibitory effects

In vitro

(Changwichit et al., 2011)

Anti-inflammatory activity

12-ursene-2,3,18,19-tetrol,28 acetate

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

Alstoprenyol

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

3β-hydroxy-28-β-acetoxy-5-olea triterpene

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

TA

the aggregation and invasion of inflammatory cells in lung tissue were inhibited, and lung tissue damage was alleviated. Oxygen saturation was increased and interleukin-1β, monocyte-chemo attractive peptide 1, interleukin −11, matrixmetalloproteinase-12, transforming growth factor-β and vascular endothelial growth factor were significantly decreased. The levels of elastin were significantly increased and fibronectin was decreased. the expression of Bcl-2 was significantly increased and the levels of nuclear factor-κB and β-catenin were decreased

In vivo

(Zhao et al., 2020a)

Picrinine

Scholaricine

19-epischolaricine

Vallesamine

Perakine N4-oxide

Raucaffrinoline N4-oxide

Vinorine N4-oxideperakine N4-oxide, rauffrin N4-oxide and vinorine N4-oxided selectively inhibited Cox-2 with 94.07%, 88.09% and 94.05% inhibition rates, respectively

In vitro

(Cao et al., 2012)

Scholarisin I

exhibited inhibition of Cox-2 selectively (>90%) comparable to the standard drug NS-398

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

Methanolic extract of dried leaves of AM

the extract at a concentration of 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg, p.o. and its fractions at 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg, p.o. showed the significant dose depen-dent antiinflammatory activity in carrageenan and dextran-induced rats hind paw edema (acutemodels) as well as in cotton pellet-induced granuloma (chronic model) in rats

In vivo

Arunachalam et al., 2002

24-ethyl-3-O-β-D- glucopyranoside

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

Lanosta,5ene,24-ethyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosideester

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

Lupeol acetate

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

3β-hydroxy-24-nor-urs-4,12,28-triene triterpene

triterpenoidesters and glycosides showed anti-inflammatory activity

In vivo

(Sultana et al., 2020)

(±)-scholarisine II

(±)-scholarisine II selectivelyinhibited the inducible COX-2 but not COX-1, also significantly inhibited 5-LOX, comparable to positive controls

In vivo

(Cao et al., 2012)

The methanol extract of the stem bark of A. boonei

extract showed significant inhibition of carrageenan-induced paw edema and cotton ball granuloma in rats, and exhibited anti-arthritic activity (P < 0.05). Acetic acid-induced peritoneal vascular permeability in mice was also inhibited.

In vivo

(Olajide et al., 2000)

The ethanolic bark extract of ASE

ASE exerted a powerful anti-inflammatory activity, with ASE-treated cells showing MCP-1 levels 928.8 ± 64.0 pg/mL (at 100 ppm) and 1074.0 ± 82.2 pg/mL (at 500 ppm) lower than control cells

In vitro

(Chandrashekar et al., 2012)

ScholarisinⅥ

exhibited inhibition of Cox-2 selectively (>90%) comparable to the standard drug NS-398

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

(E)-16-formyl-5α-methoxystrictamine

exhibited inhibition of Cox-2 selectively (>90%) comparable to the standard drug NS-398

In vitro

(Wang et al., 2013)

α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

Quercetin 3-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl (1″’ → 2″)-β-D-galactopyranoside

showed the high inhibitory activity only against maltase at an IC50 value of 1.96 mM

In vitro

(Nilubon et al., 2007)

(-)-lyoniresinol 3α-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

exhibited inhibitory activity against not only sucrase but also maltase as well with IC50 values of 1.95 and 1.43 mM, respectively

In vitro

(Nilubon et al., 2007)

(+)-lyoniresinol 3α-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

showed far lower inhibition against sucrase and maltase

In vitro

(Nilubon et al., 2007)

Anti-melanogenesis activity

Alpneumine E

showed anti-melanogenesis in B16 mousemelanoma cells with IC50 values of 71.4 µM

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2010a)

AlpneumineG

Vincamine

Apovincaminedemonstrated an anti-melanogenic activity in B16 mouse melanoma cells at IC50 values of 58.3, 68.9 and 49.8 µM.

In vitro

(Koyama et al., 2010a)

Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activities

EEAS

streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats were treated orally with EEAS (100, 200 and 400 mg/kg). Moreover, EEAS not only significantly reduced blood glucose levels, glycated hemoglobin and lipid peroxidation (P <0.001)

In vivo

(Arulmozhi et al., 2010)

DRAK2 inhibitory activity

Alstonlarsine A

demonstrated DRAK2 inhibitory activity at an IC50 value of 11.65 ± 0.63 μΜ

In vitro

(Zhu et al., 2019)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

Alstoscholarisine K

alstoscholarisine K had superior antibacterial activity than berberine (37.50 μg/mL), indicating an MIC value of 18.75 µg/mL againstis Escherichia coli

In vitro

(Yu et al., 2021)

Reversed multidrug resistance

Alstolucine A

Alstolucine Bwere found to reverse multidrug resistance in vincristine-resistant KB (VJ300) cells

In vitro

(Tan et al., 2010)

Alstolobine A

Alstolucine Fwere found to reverse multidrug resistance in vincristine-resistant KB (VJ300) cells

In vitro

(Tan et al., 2010)

N4-demethylalstogustine

19-epi-N4-demethylalstogustinewere found to reverse multidrug resistance in vincristine-resistant KB (VJ300) cells

In vitro

(Tan et al., 2010)

Scholaricine

were found to reverse multidrug resistance in vincristine-resistant KB (VJ300) cells

In vitro

(Tan et al., 2010)

Analgesic activity

Scholarisine I

(±)-scholarisine IIat 10, 20, 40 and 80 mg/kg, scholarisine I and (±)-scholarisine II reduced the writhing reflex in mice by 48.4, 40.1, 36.6 and 49.5%, respectively, comparable to aspirin at 200 mg/kg (57.2%). At doses of 50 and 100mg/kg, scholarisine I and (±)-scholarisine II decreased xylene-induced ear edemain mice by 46.0 and 41.2%, comparable to aspirin at 200 mg/kg (45.7%)

In vitro

(Cao et al., 2012)

The methanol extract of the Stem bark of A. boonei

the extract of A. boonei produced significant analgesic effect in non-inflammatory pain and inflammatory pain

In vivo

(Olajide et al., 2000)

methanol extract of A. macrophylla leaves (MEAML)

MEAML also exhibited significant dose-dependent analgesic activity, with a significant increase in response time for all doses tested in both tests

In vitro

(Chattopadhyay et al., 2004)

Antioxidant activity

EEAS

significantly reduced the levels of lipid peroxidation and bone marrow peroxidation in joint tissues and increasing the levels of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and antioxidant enzymes glutathione

In vivo

(Arulmozhi et al., 2011)

AM

AM crude extracts were found to be effective free radical scavengers given that the IC50 value was low at 0.71 mg/mL

In vivo

(Tan et al., 2019)

The root bark extract of A. boonei

ethyl acetate fraction displayed superior antioxidant activity with an IC50 of 54.25 μg/mL compared to 121.79 and 141.67 μg/mL for acetone and methanol fractions, respectively. The crude precipitate and isolated compound revealed IC50 of 364.39 and 354.94 μg/mL, respectively

In vivo

(Obiagwu et al., 2014)

Antipyretic activity

The methanol extract of the stem bark of A. boonei

the extract also significantly reduced hyperthermia in mice.

In vivo

(Olajide et al., 2000)

Anti-HBV activity

The crude extract of A. venenata bark

shows activity against HBV in HepG2.2.15 cell line

In vitro

(Bagheri et al., 2020)

pharmacological activities

Name

Description

In vivo/In vitro

Reference

CNS activity

MEAML

it was confirmed by spontaneous activity, touch, pain and vocal responses that the methanolic extract of MEAML at doses not<100 mg/kg affects the general behavioral characteristics of the treated animals. The same effect was observed for its fractions, such as fraction B

In vivo

(Chattopadhyay et al., 2004)

Anti-HSV and Anti-HDV activity

17-nor-excelsinidine

strictamine was found to possess better activity against HSV and adenovirus than those of 17-nor-excelsinidine, with EC50 values of 0.36 and 0.28 l g/mL and CC50 values of 5.01 and 3.31 l g/mL, which led to SI values of 13.93 and 11.82, respectively

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2014)

Strictamine

In vitro

(Zhang et al., 2014)

Antidiarrhoeal activity

ASE

at doses of 100–1000 mg/kg, it exerted 31–84% protection against castor oil-induced diarrhea in mice, similar to that of loperamide

In vivo

(Shah et al., 2010)

regarding both the 100 and 200 mg/kg bw at all oral doses, significant dose-dependent antidiarrheal activity was shown for all A. congensis samples, with a significant increase in time to onset and varying decreases in all other diarrheal parameters in both models compared to the untreated group

In vitro

(Lumpu et al., 2012)

Radioprotective activity

The hydro-alcoholic extracted material from the bark of ASE

the results showed more favorable postirradiation changes in the number of peripheral blood constituents in animals treated with ASE before irradiation in comparison with irradiated control mice

In vivo

(Gupta et al., 2008)

The bark of ASE

the extract was found to re store the total leucocytes and differential leucocytes (lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and non-neutrophilic granulocytes) count in the A. scholaris extract pretreated animals as compared to the irradiated control group. The data clearly indicate that the A. scholaris extract significantly reduced the deleterious bioeffects of radiation on peripheral blood

In vivo

(Gupta et al., 2011)

Anti-pulmonary fibrosis

TA

the administration of TA significantly improved pathological changes in the lungs, reducing levels of Krebs von den Lungen-6, lactate dehydrogenase, transforming growth factor-β, hydroxyproline, type I collagen, and malondialdehyde, and increasing superoxide dismutase activity in serum and lung tissue

In vivo

(Zhao et al., 2020c; Zhao et al., 2020a)

The proportions of the different types with alkaloids in the genus Alstonia.

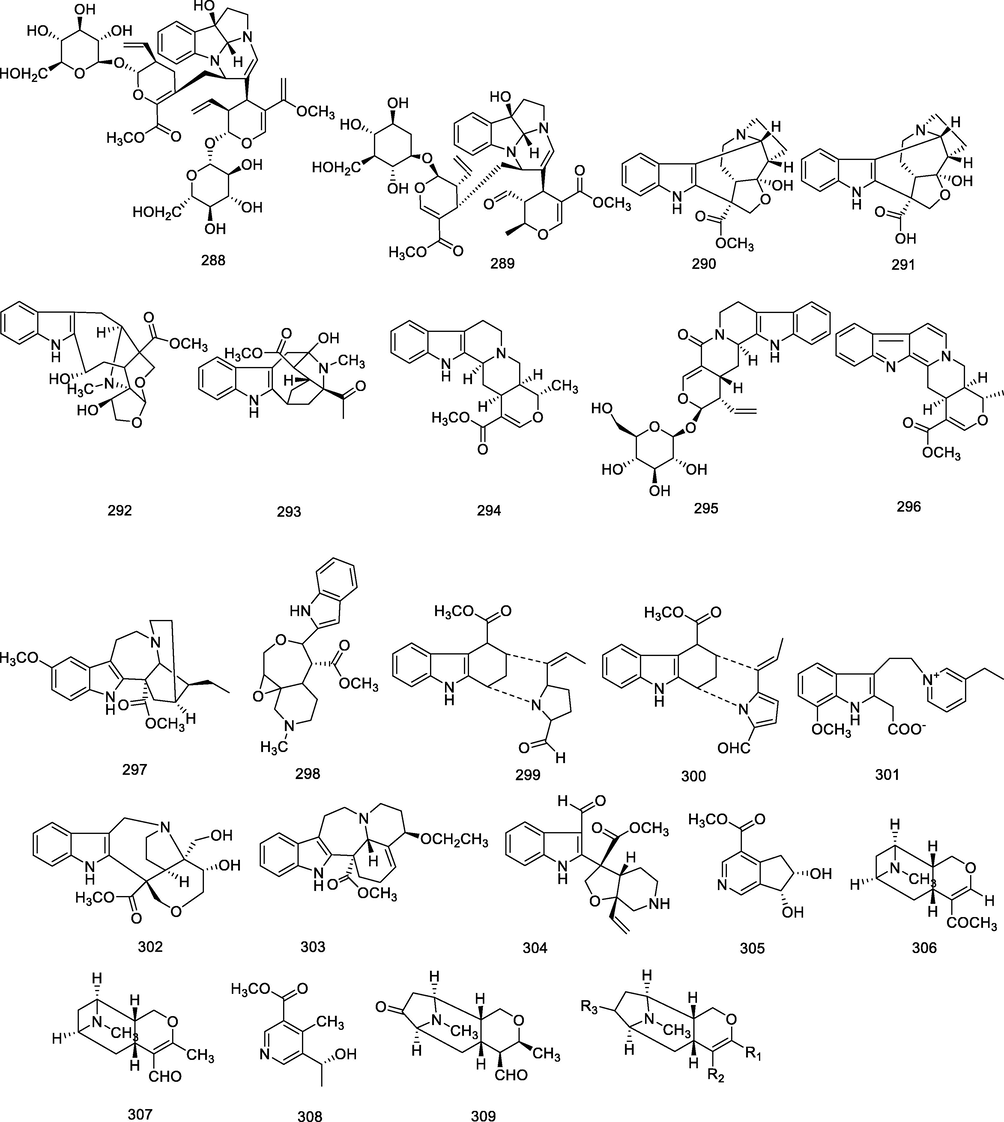

4.1.1 Corynantheine-strychnine alkaloids (1–157)

Corynantheine-strychnine alkaloids mainly include akuammiline type (1–94), corynantheine type (95–112), strychnine (113–146) and yohimbine types alkaloids (147–157). Corynantheine-strychnine alkaloids are primarily detected in different parts of A. scholaris and A. macrophylla.

Among them, akuammiline type alkaloids are the most abundant. The name akuammiline alkaloids was derived from the local name for the Picralima klaineana tree growing in Ghana (formerly called as the Gold Coast) - Akuamma (Henry et al., 1952). These compounds were characterized by a bridging ring framework having a rigid structure (Duan, 2018). Then, most corynantheine alkaloids possess characteristic 6/5/6/6 ring systems. In addition to A. scholaris and A. macrophylla, corynantheine alkaloids were also available from Alstonia angustifolia A. DC. and A. mairei. The core structure of strychnine alkaloids was extraordinarily compact with its twenty-four skeletal elements (21 radical, 2 nitrogens, 1 oxygen) forming seven fused and/or bridged rings (1 2 7) (Zlotos et al., 2022), in addition to contain 6 chiral centers. Yohimbine alkaloids have a less complex structure, possessing characteristic 6/5/6/6/6 ring systems (147–157) containing 5 chiral centers; the C-3 and C-16 sites are mostly cis-type structures in the genus Alstonia (147–149 and 156). In Table 2, the structure of corynantheine-strychnine alkaloids. are listed.

4.1.2 Sarpagine, macroline, and ajmaline alkaloids (158–240)

Sarpagine (158–174), ajmaline (175–201) and macroline alkaloids (202–240) are three structurally related indole alkaloids. Sarpagine alkaloids were mostly produced in the stem bark and leaves of Alstonia penangiana Sidiy. (Yeap et al., 2020). Most of the ajmaline alkaloids were in the leaves of A. macrophylla and the whole plant of Alstonia yunnanensis Diels (Arai et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2012). The macroline alkaloids were also detected in A. yunnanensis, A. macrophylla, A. penangiana and A. angustifolia (Kam and Choo, 2004a; Yeap et al., 2018; Kam et al., 2004; Kam and Choo, 2004a). Most of them had four stereocenters, which are C-3, C-5, C-15, and C-16 (158–166 and 203–240) (Lewis, 2006). In Table 3, the relevant structures of the compounds in the sarpagine macroline, and ajmaline alkaloids are shown.

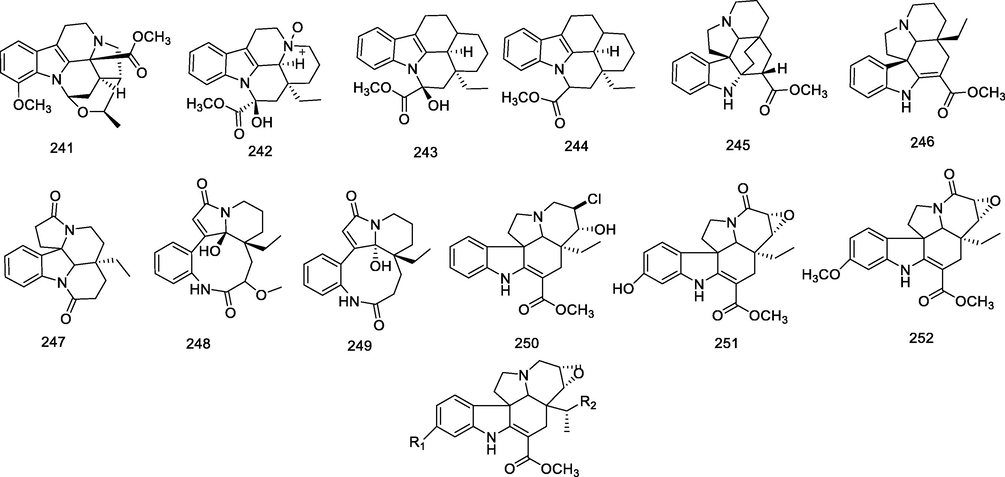

4.1.3 Eburnamine and kopsifoline alkaloids (241–261)

These alkaloids include primarily eburnamine and kopsifoline types, possessing characteristic 6/5/6/5/6 ring systems in the genus Alstonia. Eburnamine alkaloids were mainly obtained from the trunk of Alstonia rostrata C.E.C. Fisch. and the leaves of Alstonia pneumatophora Backer ex Den Berger (241–244) (Koyama et al., 2010a, 2010b; Zhong et al., 2017). Kopsifoline type alkaloids (245–261) were mainly present in different parts of A. angustifolia, A. mairei and A. yunnanensis (Goh et al., 1989; Cao et al., 2012; Li et al., 2022a, 2022b; Tan et al., 2010). A summary of the structures relevant to the compounds in the eburnamine and kopsifoline types alkaloids is given in Table 2.

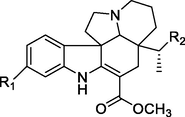

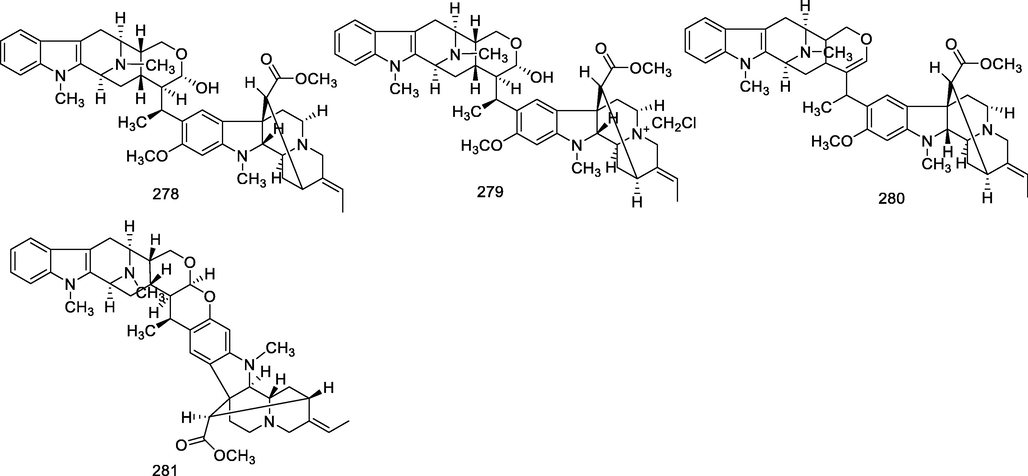

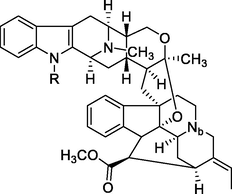

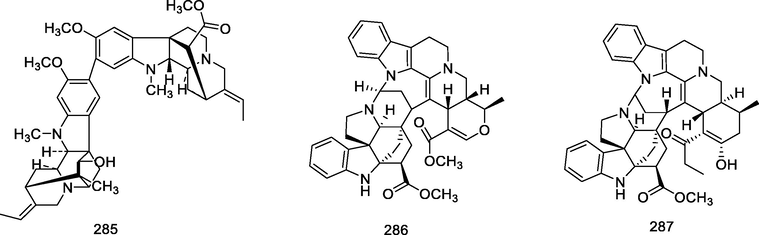

4.1.4 Bisindole alkaloids (262–287)

Bisindole alkaloids are polymerized from the same or different two monoterpene indole alkaloids, which are complicated in structure. The main bisindole alkaloids contained in the genus Alstonia were the macroline‐ajmaline type (262–264), macroline‐pleiocarpamine type (265) (Lim et al., 2013), macroline‐macroline type (266–277) (Lim, et al., 2012), macroline‐akuammiline type (278–281) (Yeap et al., 2018), macroline‐corynantheine type (282–284) and akuammiline-ajmaline type (2 8 1), etc. A recently conducted study (Wang et al., 2021) showed that rupestrisines A and B (285–287) were an unprecedented yohimbine-kopsinine type dimeric indole alkaloid. In Table 3, the structures of relevant compounds in bisindole alkaloids are shown.

4.1.5 Other structural alkaloids (288–319)

In addition, there are several other types of indole alkaloids (288–304). For example, alstrostines A and B derived from the leaves of A. rostrata with a 6/5/5/6 tetracyclic system (288–289) (Cai et al., 2011). Recently two vobasinyl-type alkaloids, alstolarine A (2 9 2), alstolarine B (2 9 3), were yielded from the A. scholaris leaves (Zhang et al., 2020).

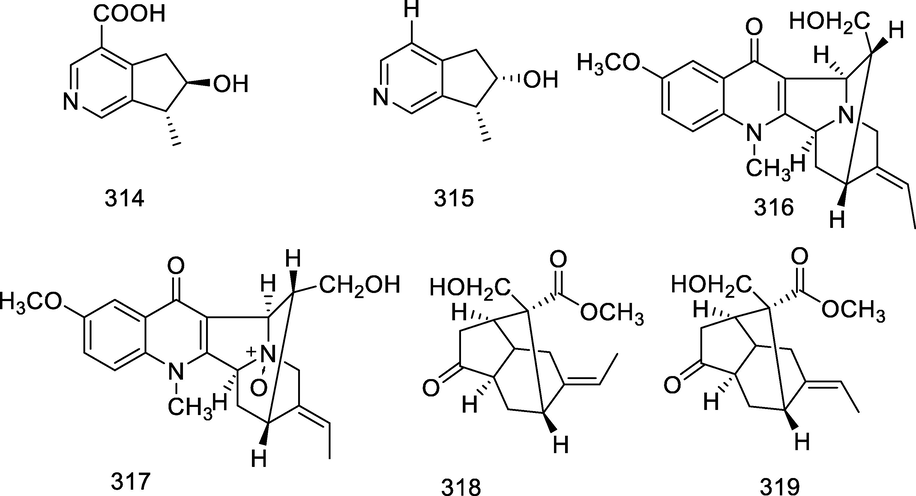

In addition to indole alkaloids, there are some non-indole alkaloids (305–325). For example, Yeap et al. discovered the first quinolone alkaloids isolated from Alstonia (316–317) (Yeap et al., 2020). The relevant structures of the compounds in other types of alkaloids are shown in Table 4.

4.2 Terpenoids (320–366)

Terpenoids refer to different saturated derivatives that satisfy the (C5H8) n-pass formula and its oxygen content. It can be considered as a class of natural compounds consisting of isoprene or isopentane linked in different ways. The skeletons of the terpenoids in the genus Alstonia are predominantly iridoids (320–330) and triterpenes (331–362). Iridoids are mainly distributed in the stem bark of A. macrophylla and A. scholaris. Iridoids usually form iridoid glycosides with sugars (320–321 and 330), most of which are glucose, with a variety of physiological activities, such as stimulating gallbladder, strengthening abdomen, and anti-inflammatory. Apart from that, some triterpenoids were isolated in the genus Alstonia. These compounds may exist in nature with free form or with glycosides or esters. C-3 position combined with glucose to form triterpene saponins or glucopyranoside esters (Sultana et al., 2020). Such as, lanosta 5ene, 24-ethyl-3-O-D-glucopyranoside (3 5 8) was triterpene saponin; lanosta 5ene 24-ethyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosideester (3 5 9) was glucopyranoside ester. Triterpenoidesters and glycosides had anti-inflammatory activities (Sultana et al., 2020).

4.3 Flavonoids (363–379)

Flavonoids are widely distributed in nature with common C6-C3-C6 parent nucleus. The C-2, C-3 or C-4′ of flavonoids could be combined with sugars to form flavonoid glycosides (363–366 and 368–369) (Parveen et al., 2010; Nilubon et al., 2007; El-Askary et al., 2013). At present, 16 flavonoids have been collected from the genus Alstonia.

4.4 Other compounds (380–392)

In addition to the aforementioned compounds, the genus has also obtained fatty acids (3 8 0), phenolic acids (381–389), lignans (390–391), and esters (3 9 2). The C-3 position of lignan was linked to glucose to form a glycoside with strong α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (Nilubon et al., 2007).

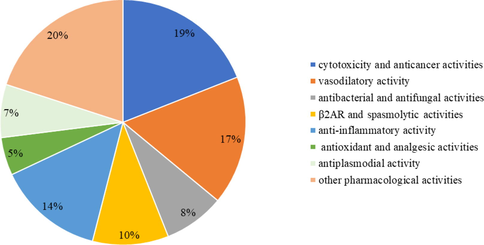

5 Pharmacological activities

Through extensive modern pharmacological experimental researchs indicated that Alstonia played an essential part in the cytotoxicity, anticancer, vasodilatory, β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) activity, antiplasmodial, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, analgesic and radioprotective activities, etc. The pharmacological activities of genus Alstonia can be found in Table 5. Fig. 2 shows the different pharmacological activities of Alstonia plants.

The different pharmacological activities of Alstonia plants.

5.1 Cytotoxicity and anticancer activities

In 2017, cancer was the second most common cause of mortality worldwide and a major load on wellness systems. Several researches reported that in laboratory animal models, compounds possessing antioxidant or anti-inflammatory properties, sunch as certain phytochemicals, had been found to inhibit tumorigenesis, promotion and development (Chesson and Collins, 1997; Hocman, 1989). According to the statistics of literature, the crude extracts and compounds of Alstonia plants had anti-cancer effects in numerous in vivo and in vitro experiments. ASERS (the alkaloid fraction of A. scholaris) was considered the most efficientt doses of 210 mg/kg (Jagetia and Baliga, 2006). This opens the way for the genus Alstonia to be an anti-tumor, attracting the attention of many scholars. Moreover, Baliga reported that echitamine (35) had cytotoxic effects on HeLa, HepG2, HL60 and other models (Baliga, 2010). Moreover, one recent study (Spiegler et al., 2021) further demonstrated that A. boonei extracts were effective for common pediatric tumor types (leukemias and Ewing sarcoma). 15-hydroxyglutathione A (78) was identified as the effective ingredient of A. boonei extract using bioassay-guided approach. The IC50 value for MCF-7 cells was 26 μM. This is the first time that compounds of A. boonei are mentioned. Preliminary mechanistic studies demonstrated that in G2/M phase, apoptosis increased and cell cycle arrested.

5.2 Vasodilatory activity

Vasodilators help treat cerebral vasospasm and hypertension as well as improve peripheral circulation. More and more species of genus Alstonia are being identified to have vasorelaxant activities. Arai et al. found that vincamedine (1 8 5) showed potent vasodilatory activity. The mechanism of vincamedine (1 8 5) might be the inhibition of Ca2+ influx through volte-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCs) and/or receptor-operated Ca2+ channels (ROCs) (Arai et al., 2012). In addition to the above, they observed the presence of two substituents at the N-1 and C-17 positions, which may be critical in showing vasodilatory activity (Arai et al., 2012)(). Obviously, the activity of compounds varies with their structure.

5.3 Antibacterial and antifungal activities

Multidrug resistance is a leading challenge in both developed and developing countries. There is an urgent need to tackle multi-drug resistance. Through many experiments, some scholars found that Alstonia species had antibacterial and antifungal activity. Khan et al. found that there was excellent antimicrobial activity and broad antimicrobial spectrum in crude methanolic extracts made from leaves, stems and root barks of A. scholaris, in particular the butanol part of A. scholaris. However, all fractions were inactive against the tested moulds (Khan et al., 2003). Singh et al. demonstrated that Δ3-alstovenine (1 5 5) was a quaternary alkaloid. At concentrations of 250–1000 mg/L, spore germination of the tested fungi was mostly inhibited (Singh et al., 1999). In addition to alkaloids with antifungal activity, flavonoid glycosides had the same activity. For example, a compound with antibacterial activity named tricin-4′-O-β-L-arabinoside (3 6 3) was obtained from the leaves of A. macrophylla (Parveen et al., 2010).

5.4 β2AR and spasmolytic activities

β2AR agonist is one of the most commonly used drugs for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hou et al. used a liquid chromatography with ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LCMS-IT-TOF) system to isolate alkaloids with β2AR agonists activity from A. scholaris. In addition, the alkaloids were identified to have a synergistic effect in an isolated guinea pig model (Hou et al., 2012a). In vitro experiments proved that akuammidine (1 6 1) and Z-alstoscholarine (2 9 9) were new indole alkaloid-type β2AR agonists. Shah et al. showed that the A. scholaris extract (ASE) possessed spasmolytic effect. This mechanism might be mediated by calcium channel block (CCB) (Shah et al., 2010).

5.5 Anti-inflammatory activity

Alkaloids are potent anti-inflammatory compounds found in the genus Alstonia. Cao et al. obtained eight compounds from A. yunnanensis, including raucaffrinoline N4-oxide (1 8 1), vinorine N1, N4-dioxide (1 8 2), and vinorine N4-oxide (1 8 3) exhibited selective inhibition of Cox-2 with 94.77%, 88.09% and 94.05% inhibition, respectively (Cao et al., 2012). Wang et al. obtained three monoterpene indole alkaloids from 70% ethanol extract of Alstonia rupestris Kerr leaves. Scholarisin I (1), scholarisinVI (26) and E-16-formyl-5α-methoxystrictamine (39) had elective inhibition of Cox-2 with inhibition rates of 96.4%, 95.5%, and 92.0% (Wang et al., 2013). A recent study (Zhao et al., 2020a, 2020c) suggested that TA obtained from A. scholaris leaves had the potential to be an effective new drug to treat emphysema. TA not only inhibited airway wall inflammation and airflow resistance, as well as improved pulmonary elasticity and protease/antiprotease balance.

5.6 Antioxidant and analgesic activities

Oxidative damage can lead to various diseases. Therefore, the study of antioxidant drugs has attracted the attention of medical workers. Studies demonstrated (Arulmozhi et al., 2011) that the ethanol extract of A. scholaris leaves (EEAS) significantly decreased lipid peroxidation and myeloperoxidase levels in the joint tissue. The bark of the Philippine A. macrophylla (AM) and the root bark extract of A. boonei demonstrated antioxidant activity against DPPH radical (Tan et al., 2019; Obiagwu et al., 2014). Similarly, the analgesic activity of Alstonia plants has also been identified through a large number of experiments. Compared to aspirin, alkaloids from A. scholaris leaves, especially scholarisine I (1) and (±)-scholarisine II (2), had the same analgesic efficacy at 200 mg/kg (Cai et al., 2010). Acetic acid-induced writhing and early and late paw licking in mice were observed to be reduced, indicating that the methanolic extract of A. boonei stem bark produced significant analgesic activity (Olajide et al., 2000).

5.7 Antiplasmodial activity

Malaria remains a stubborn disease, ravishing communities in about 100 countries. The cause of this disease‐Plasmodium parasites transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes‐had been widely understood since the late 19th century (Cox, 2010). Consequently, it is exceptionally critical to recognize a new drug against the malaria parasite. In many African countries, Alstonia congensis Engl. is a medicinal plant. Crude extracts and single compounds obtained from the root bark of A. congensis displayed antimalarial activity when tested in vitro and in vivo (Kanyanga et al., 2019). In addition, the combination of the genus Alstonia with other traditional Chinese medicines were identified to exhibit antiplasmodial activity. Tepongning et al. reported that the stem bark combination of the K. ivorensis and A. boonei showed antiplasmodial activity with large dose intervals between therapeutic and toxic doses in the murine malaria model, which was used as an antimalarial prophylactic (Tepongning et al., 2011).

5.8 Other pharmacological activities

Other than those listed above, Alstonia had been proved to possess a variety of other pharmacological activities. Alstiphyllanines E (20) and F (12) showed moderate Na+-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitory activity. 10-methoxy-N1-methylburnamine-17-O-veratrate (15) exhibited potent inhibitory activity (Arai et al., 2010). Compound alstonlarsine A (1 2 8) was isolated from A. scholaris and had death associated protein related apoptotic kinase (DPAK2) inhibitory activity (Zhu et al., 2019). A. scholaris bark aqueous extracts in the 50 and 100 mg/kg body weight were able to stimulate non-specific immune response inhibitory activity (Iwo et al., 2000). Weiming et al. found that the crude alkaloidal extracts from A. yunnanensis root exhibited marginal activity against experimental tumour U14 in mice (Weiming et al., 1983). Hirasawa et al. found that isolated constituents of A. pneumatophora showed antimelanogenesis in B16 mouse melanoma cells, specifically alpneumine E (1 2 5), alpneumine G (2 4 2), vincamine (2 4 3) and apovincamine (2 4 4) (Hirasawa et al., 2009).

In addition, extracts with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity were acquired by drying the methanolic water of A. scholaris (Nilubon et al., 2007). Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activities of A. scholaris leaves were also reported (Arulmozhi et al., 2010). Chattopadhyay et al. revealed CNS activity of A. macrophylla leaf extracts (Chattopadhyay et al., 2004). Alstolarine B (2 9 2) showed moderate acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity (Zhang et al., 2020). 17-nor-excelsinidine (1 0 9) and strictamine (43) were isolated from A. scholaris and showed significant inhibitory activity against herpes simplex virus (HSV) and adenovirus (ADV) (Zhang et al., 2014). A recent research (Bagheri et al., 2020) demonstrated that Alstonia venenata R. Br. bark was effective against hepatitis B virus (HBV) in benzene, isopropanol and methanol fractions. ASE also showed significant radioprotective activity. Compared with irradiated animals, ASE pretreatment significantly increased glutathione levels in the serum and liver (Gupta et al., 2008).

6 Toxicity

In recent years, some diseases, such as cancer, bacterial infections, etc., have developed multi-drug resistance to the drugs used, which makes it more difficult to treat these diseases. The excellent pharmacological activity of genus Alstonia, particularly A. scholaris, can be used as a natural drug treasure trove for clinical use. However, there is limited knowledge of its potential toxicity and therefore toxicity studies are essential.

Baliga et al. administered different doses of hydroalcoholic extracts of A. scholaris to rats and observed the acute and subacute toxic effects of the extracts on rats. They found that oral administration of the hydroalcoholic extracts of A. scholaris were not toxic to mice at a dose of 2000 mg/kg body weight. However, the highest number of animals died after intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 1100 mg/kg body weight. Interestingly, they also observed that the acute toxicity of the mice depended on the season in which the plants were collected. The acute toxicity was highest for plants collected in summer, followed by those collected in winter (Baliga et al., 2004). Baliga and Shrinath further studied A. scholaris. It was demonstrated that extracts of A. scholaris stem bark and leaves did not cause death or adverse effects at a dose of 2000 mg/kg body weight. However, when injected intraperitoneally at high concentrations, mice demonstrated systemic and developmental toxicity (Baliga and Shrinath, 2012). The alkaloids isolated from the leaves of A. scholaris were also proved to be non-toxic (Zhao et al., 2020b, 2020d). While the safety of A. scholaris stem bark has been evaluated, the lack of rigorous toxicological studies and the diversity of experimental animals are necessary to further demonstrate the pharmacology and safety of high concentrations of A. scholaris stem bark extracts prior to clinical use. Zhao et al. conducted a comprehensive preclinical program including acute and subchronic studies with beagle dogs as a model. Research revealed that indole alkaloids at 20, 60 and 120 mg/kg body weight showed no signs of toxicity except for vomiting and drooling in most dogs. Alkaloid extracts of A. scholaris leaves did not cause adverse effects or death in beagle dogs (Zhao et al., 2020e). In addition, indole alkaloids are not genotoxic in the Ames test, mammalian chromosome aberration test, as well as in the micronucleus test (Zhao et al., 2020d).

Therefore, the current study indicates that the stem and leaves extract of A. scholaris are safe and provides toxicological data for conducting clinical trials.

7 Clinical research

On the basis of these findings, together with a series of preclinical studies and safety assessments, the genus Alstonia, with special reference to A. scholaris, has been developed as a new botanical drug and further approved by the Chinese Food and Drug Administration for Phase I/II clinical trials (Shang et al., 2010a, 2010b).

Li et al. evaluated the safety of A. scholaris leaves alkaloids capsule (CALAS) (No. 2011L01436), when administered orally at different doses. The clinical study was conducted in 40 healthy volunteers who were divided into four groups (n = 10 per group) and received different doses of CALAS ranging from 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg to 120 mg. On August 26, 2015, the trial was registered (https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=11736) with the number ChiCTR-IPR-15006976 (Li et al., 2019). During the trial, two minor adverse events were observed, although both were related to individual physiological variability and were safe for volunteers at the current dosing regimen (Li et al., 2019). Gou et al. further assessed the clinical safety and tolerability of CALAS. In distinction to Li et al., subjects were randomized to receive either CALAS or then placebo in one of single ascending dose of 8, 40, 120, 240, 360, 480, or in one of multiple ascending dose of 40 or 120 mg, three times daily for 7 days. The results showed that in healthy Chinese volunteers, CALAS from the Alstonia scholaris leaves proved to be safe and tolerated with no unexpected or clinically relevant safety concerns at a single dose of 360 mg and up to 120 mg three times daily (Gou et al., 2021). In addition, clinical population pharmacokinetic, metabolomic and therapeutic data are also crucial to provide guidance on patient dosing. Li et al. performed a metabolomic analysis to determine biomarkers associated with treatment efficacy in CALAS from the Alstonia scholaris leaves and to assess efficacy and safety depending on symptoms and adverse events in the clinic (Li et al., 2022a, 2022b). This study identified changes in lysophosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, and amino acids as possible indirect markers in the treatment of acute bronchitis, and there were no serious adverse effects in clinical trials (Li et al., 2022a, 2022b). Pharmacokinetic, metabolomic, and therapeutic data as well as clinical safety and tolerability evaluations of CALAS from the Alstonia scholaris leaves in clinical populations have demonstrated a reliable safety profile, only showing minor, transient adverse reactions.

In conclusion, the excellent pharmacological activity and clinical Phase I data of A. scholaris further support the Phase II clinical trial. A. scholaris can be further developed into products used to treat patients who have respiratory diseases.

8 Conclusion and future perspectives

Alstonia genus is traditionally used to heal human diseases. Because of its remarkable pharmacological activity, it has attracted the attention of many scholars. In the current work, we comprehensively review the composition and pharmacological activities of genus Alstonia and discussed its toxicity for further study and clinical application. So far, over 400 chemical compounds have been obtained from genus Alstonia, such as alkaloids, triterpenes, flavonoids, fatty acids, phenolic acids, lignans, and volatile oils. Alkaloids are considered to be the main effective components, with the most widespread being MIAs among Alstonia plants. Nonetheless, compared with alkaloids, non-alkaloid components such as flavonoids and triterpenes have not been studied in depth. And some species have been less studied, such as A. pneumatophora and Alstonia balansae Guillaumin, etc. It is promising to deploy a bioactivity-oriented isolation strategy to locate additional bioactive components. Because the diversity of chemical structures determines the difference in biological activity and determines the clinical application, phytochemical research focuses on chemical components with fewer studies or better efficacy.

The exploration of bioactive molecules and multi-component interactions is important for the clinical application in Alstonia plants. For example, 15-hydroxyangustilobine A (78) is identified in A. boonei leaves as an effective constituent for the treatment of tumors. Alstonia plants have a variety of bioactivities, but their mechanism research is not in-depth, and the structure–activity relationship is not clear. In order to further make drugs from the compounds contained in Alstonia plants into drugs, the mechanisms involved in the biological activity and structure–activity relationships of chemical composition must be studied in depth.

In summary, the aim of this review is not only to contribute to a basis for analyzing the bioactive mechanisms of important natural products, but also to provide potential development value for studying new drugs. Further research on the molecular and cellular mechanisms as well as clinical applications is needed for the exploitation of Alstonia plants. Only by bridging the gap between bioactivity-related mechanisms and structure–activity relationships of chemical components can the development of Alstonia plants be further promoted.

Author contributions

Mi-xue Zhao collected the information and drafted the manuscript; Jing Cai and Ying Yang helped to modify the format of the manuscript; Wen-yuan Liu and Jian Xu were involved in the preparation of tables; Wei Li and Toshihiro Akihisa edited the pictures; Jie Zhang analyzed the manuscript. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Useful plants of Ghana: West African uses of wild and cultivated plants; practical action publishing: Rugby. Warwickshire, United Kingdom. 1990;1990

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An exploratory ethnobotanical study of the practice of herbal medicine by the Akan peoples of Ghana. Altern Med Rev.. 2005;2:112-122.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Total synthesis of (+) -scholarisine A. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2012;134:4037-4040.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A Review of the ethnobotany and pharmacological importance of Alstonia boonei De Wild (Apocynaceae) ISRN Pharmacol.. 2012;2012:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary of Indian Medicinal Plants. India: Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Lucknow; 1992. p. :27.

- Phytochemical and antimicrobial study of Alstonia scholaris leaf extracts against multidrug resistant bacterial and fungal strains. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2019;32:1655-1662.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous, 1985. The Wealth of India: raw materials. Publications and information Directorate, Council of Scientific and Indus-trial Research, New Delhi, pp. 201‐204.

- Alstiphyllanines E-H, picraline and ajmaline-type alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla inhibiting sodium glucose cotransporter. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2010;18:2152-2158.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alstiphyllanines I-O, amaline type alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla showing vasorelaxant activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2012;20:3454-3459.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activity of leaves of Alstonia scholaris Linn. R. Br. Eur. J. Integr. Med.. 2010;2:23-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-arthritic and antioxidant activity of leaves of Alstonia scholaris Linn. R.Br. Eur. J. Integr. Med.. 2011;3:83-90.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of anti-Inflammatory activity of Alstonia macrophylla Wall Ex A. DC. leaf extract. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:632-635.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Asolkar, L.V., Kakkar, K.K., Chakre, O.J., (Eds.), Second Supplement to Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants with Active Principles (Part 1 (A/K)). Publications and Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi 1992, pp. 51/52.

- Phytochemical screening of Alstonia venenata leaf and bark extracts and their antimicrobial activities. Cell Mol. Biol.. 2020;66:224-231.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alstonia scholaris Linn R Br in the Treatment and Prevention of Cancer: Past, Present, and Future. Integr. Cancer Ther.. 2010;9:261-269.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]